Despite its popularity and apparent accessibility, I often find Impressionism to be some of the most difficult and challenging art to look at. That’s in part because of the erosive quality of its popular ubiquity, the way specific paintings (Van Gogh’s Starry Night, Monet’s Water Lilies come to mind) are so often seen in reproduced fashion on anything from dorm room posters to Hallmark cards that the work can register as a logo or brand. The style, and all its lilting breathy beauty, can be so pretty, so innocuous, so ubiquitous that what made it important or interesting as art can be lost to contemporary eyes. It becomes a stand-in, a signifier of itself. There’s an almost Warholian glaze – the art image as cultural brand – that makes it difficult to see what made the work so revolutionary in its day.

The other challenge I find with any Impressionism exhibition is getting over reading the successive works as merely notches on the timeline of a familiar art historical arc. It goes something like this: Once upon a time painters made pictures, but then they began to experiment with color and form. Manet begat Monet who begat van Gogh who begat Cezanne who begat Picasso — or some similar butchered progression – and voilà! We’ve arrived safely in modernism. Looking at Impressionistic art, it can be tempting, particularly when you’ve tired to the postcard versions, to reduce it all as an affected, pretty-fied prelude to modernism — a breaking open of the medium, early grappling with paint in a post photographic world, an assertion of new justifications, new definitions, new forms, and new attention to the physical qualities of the work of art – surface, color, flatness, manipulation of perception.

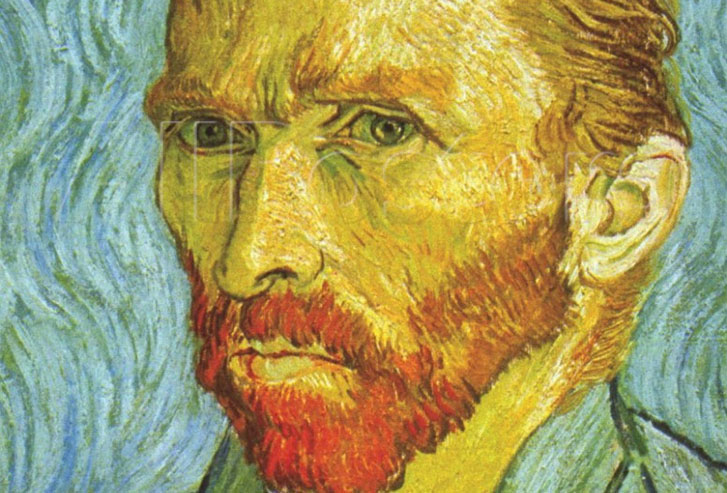

The exhibition at the Kimbell Art Museum, Faces of Impressionism, does as good a job as one can expect of trying to throw viewers off these familiar interpretative scents, so to speak. Sure, we have some postcard classics, like van Gogh’s Self Portrait, a diminutive little hallucinatory picture that you’ve seen reproduced a thousand times. And sure, there’s a loosely chronological laying out of the storyline in the gallery in the new Renzo Piano Pavilion, working around counter clockwise from the 1860s to the 1910s. But the portrait as a singular subject foils lazy readings of the exhibition, as does an airy, open-floored exhibition design made possible by the floating walls in the new gallery. As a result, rather than plodding along the timeline, I found myself wandering about, zig-zaging, and letting each portrait make its case on its own terms.

In doing this, what I discovered was another art historical storyline – one that was not so much stylistic as literary. Look closely at the portraits of Degas, who is the unexpected star of the Kimbell’s exhibition. There’s a subtle psychology revealed in every expression, reinforced by a perfectly evocative sense of weight and gesture, and a formal composition of groups of people – whether families or friends or orchestras – that conjures a suggestive and legible feeling of dramatic potency. We get the sense that these artists are wrestling their art away from conventions, not just stylistically, but politically. The portrait becomes a window into the inner lives of their subjects, but that internality reflects back out onto the dynamics of their social lives. And the subjects are often the social circles of the artists — or the artists themselves.

The artists’ world is on full display in these paintings in such a way that we can read these paintings as the artists’ efforts to reconcile the relationship between their art and their world. Among the early examples of this, I particularly enjoyed the cavalier ease – swagger at rest – of the subject posing in Charles Carolus-Duran’s The Convalescent (c. 1860); and Courbet’s Madame Proudhon, Wife of the Philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon is a deceivingly complicated image, the face of the woman offering itself and hiding something simultaneously. We see a similar complication in the uncomfortable gaze of Degas’ Portrait of a Young Woman (1867), which sits across the gallery from Courbet’s painting, a portrait that is striking precisely because it is at once so simple, so common, and so honest.

This searching for a deeper honesty in the depiction of individuals parallels a similar attempt at psychological realism that was being explored in the literature of the time. Some of the most exciting paintings here are the ones in which we see these subjective and stylistic experimentations occur concurrently. In Degas’ The Orchestra of the Opera (1868-1869), his favorite subject – those feathery skirted ballerinas – make an appearance near the top of the canvas, their heads cropped off by the edge of the frame. Instead, of being swept up in the dancer’s wistful beauty, our focus gets lost in the gaggle of faces in the orchestra pit. Each musician is rendered in a way suggestive of a particular identity and personality, and together they read like notes on a score, an expressive ensemble. Looking at this picture helps focus our attention on everything that is going on beneath the surface of Degas’ famous In a Café (Absinthe) (1876-76), which hangs nearby.

There are plenty of these kinds of immersive scenes to get lost in. You could write a novel inspired by the subtle dynamics at play in Manet’s The Balcony, or Jacques-Émile Blanche’s The Halévy Family (1903). Renoir, who is heavily represented in the exhibition, offers the clearest exposition of how these psychological concerns become internalized in the expressive quality of his style. I still have trouble getting too excited Renoir’s sticky sweet, wistful little beauties all adorned with hazy pastels, but one of his late works here, Gabrielle With a Rose, 1911, is also one of the most memorable pieces in the exhibition. It is evocative of a kind of tenuous balance between sensuality and troubled self-possession that lends the painting a power that almost undermines its readily available beauty. There’s a similar tension in a very early piece by the artist, Young Boy With a Cat (1868), which depicts a naked pubescent boy from behind. He peers coyly over his shoulder towards the viewer; its ambiguous, startling, and provocative sexuality seems to anticipate both Balthus and Richard Prince.

The omission of landscapes takes the focus away from the transcendental quality of the Impressionist project, and it also has the side effect of making the innovations of the post-impressionists feel all the more staggering and new. Toulouse-Lautrec’s strong lines and graphic sensibility read well juxtaposed to van Gogh’s work, just a few steps away. Gauguin, that eccentric and uncomfortable nut, leers out at us from his Self Portrait with The Yellow Christ, a strange, though arresting little picture. Van Gogh’s portrait, built out of its brush licks of vibrant, unnatural color, looks like a radiating LSD hallucination; but his L’Arlesienne, Portrait of Madame Ginoux, 1888 just steps away, is a wonderful demonstration of the artist’s forcing of flatness and segmentation of field, which breaks up the canvas in such a way that it brings the composition together into a more cogent, singular unity.

Across the way, Cézanne takes it a step further. Perhaps my favorite single piece in the show is his portrait of his son Paul. It’s so simple and flat, and yet sensual and concise and perfectly contained and of itself. In its style smacks something of both Etruscan urns and Giotto frescos, and the boy’s head, a Brancusi-like ovoid sitting on a cylindrical neck, is rendered with such geometric simplicity it makes it look as if Picasso hardly had to do anything at all to invent Cubism. With this image, Faces of Impressionism does bring us to the brink of modernism, as any exhibition of its kind inevitably does. Only, this time, I felt like I had arrived on a new road.