Alejandro Jodorowsky is one of the most colorful and eccentric filmmakers of the last 50 years, having directed such midnight-movie cult favorites as El Topo and The Holy Mountain in the early 1970s.

Documentary filmmaker Frank Pavich was a fan of those films, but what interested him more was the film Jodorowsky’s didn’t make, namely his outrageously ambitious 1975 adaptation of Dune, the seminal science-fiction novel by Frank Herbert. The behind-the-scenes stories read like tall tales — how Jodorowsky assembled a team of “spiritual warriors” that included artists and technicians from around the world, few of which had any moviemaking experience; how he claimed to have agreements for the involvement of Mick Jagger, Orson Welles, and Salvador Dali for acting roles, and Pink Floyd for the soundtrack; and how he compiled a massive book of storyboards with each scene illustrated in painstaking detail. Of course, every studio in Hollywood rejected his pitch, the financing fell through, and the epic folly was abandoned.

Pavich details all of this in Jodorowsky’s Dune, which will likely be the closest the 85-year-old Chilean director ever gets to seeing his passion project on the big screen.

“It was probably kind of cathartic for him to be able to tell these stories,” Pavich said during a recent stop in Dallas. “He got to see for the first time his vision, projected and moving like it’s supposed to, and not just pictures on a page.”

Pavich took an interest in the project because he was a fan of Jodorowsky’s earlier films and the cult following they built over the last few decades.

“It seemed like a very natural story to tell. It’s not like your average unmade film,” he said. “There’s a million unmade films, but most of them are not very well realized. It’s an unmade film that was completely realized.”

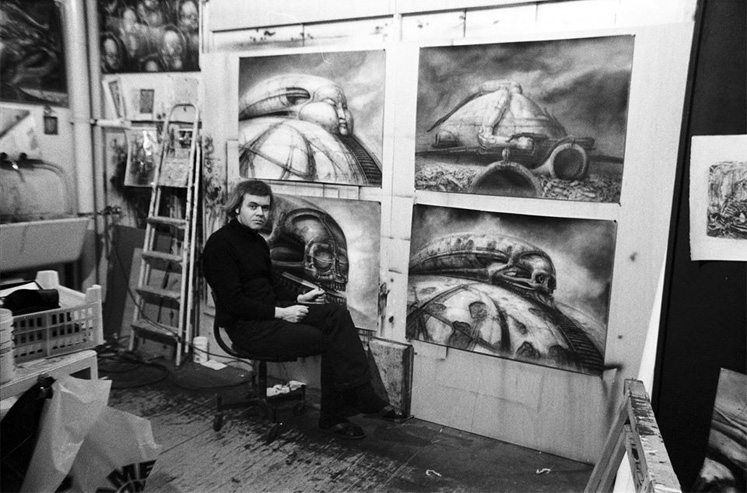

Pavich first contacted Jodorowsky about his documentary idea in 2010, and spent the next three years conducting research and filming interviews with any Dune collaborators he could track down, such as producer Michel Seydoux and artists H.R. Giger and Chris Foss.

“Once we had [Jodorowsky’s] full cooperation, it was very easy to reach out to all these people. They were completely on board,” Pavich said. “I think they still have the same level of enthusiasm for the Dune project and the same level of enthusiasm for him.”

Pavich said that loyalty stems from Jodorowsky’s belief in artists who had never worked in film before. After Dune, many of them got other, more lucrative jobs in the industry. For example, Giger went on to be a creature designer on Alien.

Although Jodorowsky’s project might have seemed like a far-fetched budgetary and logistical nightmare, Pavich said the biggest issue might have been unlucky timing. After all, David Lynch made a Dune movie less than a decade after Jodorowsky’s attempt, which turned into a critical and commercial failure. A primary difference between the two, according to Pavich, was the release of Star Wars in between, which proved the box-office viability of science-fiction epics. He even postulates that had Jodorowsky’s Dune been released, and flopped, that Star Wars might never have been given the green light.

“They made [Dune] action figures, which sounds insane. They made Topps trading cards and coloring books, thinking they were going to make a billion dollars,” Pavich said of the Lynch version. “It was just that Jodo was ahead of his time.”

So, in the fantasy world in which Jodorowsky’s vision is brought to fruition, would the finished product have been any good? Nobody can ever be sure.

“He’s never made a movie to make money. He’s doing them to tell a story or to teach people things, or to spiritually enlighten people, and I think Dune would have done that,” Pavich said. “I don’t think it would have been for everybody, but for the select, chosen few, it would have been transcendent.”