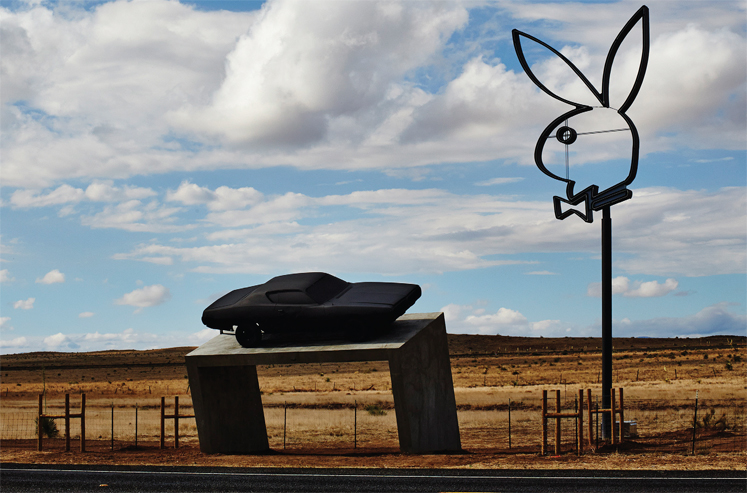

Richard Phillips’ Playboy Marfa sculpture is silly. Originally installed along a highway leading to the tiny West Texas art colony called Marfa, it consists of a tall pole topped by a neon Playboy bunny logo that stands just a few feet from a tilted concrete platform. Atop the platform sits a muscle car of some 1970s varietal, painted flat black, windows and all, so that the car looks like it was carved from graphite. There’s something pitiful about the underwhelming sight of the slumped over car out there in the grand abyss of the West Texas landscape. It’s less action in freeze frame—a monument to fast cars, virility, American road lust, vulgarity, Playboy, or whatever Phillips was after—than it is a Back to the Future-style “Ozymandias,” commercial ambivalence already ruined, sinking into the earth.

The sculpture didn’t last long in West Texas. It was removed after the Texas Department of Transportation complained that Playboy had violated the state’s prohibition of roadside advertising in the area. Playboy’s argument that it was art and not advertising didn’t fly with TxDOT. But rather than getting banished to a darkened storage facility, Phillips’ car and logo will ride again this month in a new location, outside the Dallas Contemporary, where it will accompany a large exhibition of the artist’s work.

Since the arrival of director Peter Doroshenko in 2010, the organization has demonstrated an appetite for salacious superficiality. The museum’s programming dabbles in fashion, street art, celebrity, and high-society cultures. There are occasional forays into cerebral art practice, but the space is best known for the opening parties that pack in the socialites. Critics have said these events frustrate any hope that Dallas culture can transcend the superficial stereotypes that the Contemporary gleefully repackages. Exhibitions have included Jennifer Rubell, the artist daughter of prominent Miami art collectors, whose art was to hire a number of Hispanic food service workers to prepare food for the museum’s patrons; Ezra Petronio, the photographer who covered a wall with Polaroids of celebrities; and Erwin Wurm, the Austrian artist whose sculptures instructed viewers to drink vodka while viewing the work. In January, French street artist JR put a photo booth in the gallery. Visitors had their pictures taken, printed on posters, and plastered to the gallery walls. The museum looked like someone had set off a car bomb and blown up Facebook—self-celebratory shallowness writ large. Everyone wanted to be a part of it.

Richard Phillips fits perfectly into this mix. He is best known for his photo-realist paintings of celebrities—Lindsay Lohan, the porn star Sasha Grey—that offer glossy images of famous people that celebrate popular culture’s vulgarity. That vulgarity, couched within a seemingly anodyne portrait, offers the kind of soft-handed cultural critique and palatable self-irony that make Phillips’ work beloved by wealthy art collectors, particularly in Dallas. It also makes Phillips despised by those who see his work as vacuous flattery directed at the collectors who are so desperate to snatch up his glossy commodities.

It makes perfect sense, then, that the Dallas Contemporary will open Richard Phillips alongside another controversial artist figure, Julian Schnabel. In the 1980s, Schnabel was the art world’s flamboyant, egomaniacal protagonist, famously wandering New York in his paint-splattered pajamas while wealthy collectors clamored to get their hands on his price-spiking artwork. But in the last 20 years, while he went off to reinvent himself as a successful filmmaker, Schnabel, a consummate sentimentalist, has been more or less shunned by the art establishment. The Dallas Contemporary show will be his first museum exhibition in the United States since 1988.

The pairing of Phillips and Schnabel is not only the Dallas Contemporary’s most high-profile lineup yet, but it’s also its most inspired provocation. The exhibitions bring together two artists whose fame and financial success run afoul of high minded critical consensus. The artists make art lovers uncomfortable precisely because they represent what contemporary art has largely become: an investment option, a commodity in a portfolio. Doroshenko challenges our reverent attitude toward art by forcing us to reencounter and reevaluate what we dismiss as profane.

As with Phillips and Schnabel, what bothers so many people about the Dallas Contemporary is exactly what makes it interesting. The Dallas Contemporary has become a paradoxical space. It is a museum that seems to insult as it flatters, to pander as it turns up its nose. It doesn’t play by the rules of the market or the academy. The Contemporary provokes very much the same response as a Richard Phillips painting, looking almost like a cynical critique of itself but never betraying its poker face.