Here’s the situation outlined in the New York Times’ Ethicist column. A patron gives money to his favorite art museum. An acquaintance who’s an opera fan asks said patron to donate to an opera company as well. The patron doesn’t like the opera, but he decides to strike a deal. He’ll give $10,000 to the opera if the acquaintance gives $10,000 to the museum. The acquaintance agrees, but then four years later, the patron finds out the acquaintance has only been giving $1,000, instead of the agreed upon $10,000. When the patron confronts him, the acquaintance just laughs it off. The patron is miffed. How should he respond?

Off the bat, the Times’ Ethicist Cluck Klosterman makes an important observations. Since the patron increased the amount of money he gives to charity by adding the opera to his charitable portfolio only because the acquaintance agreed to return the favor by giving the same amount to the museum, why didn’t the patron just give the extra money to the museum in the first place? The reason:

“You wanted this specific guy to donate to your preferred charity. So what you’re really asking is how to ethically respond to a personal betrayal that one party finds offensive and the other finds comedic.”

Klosterman walks through a few options the patron proposed for responding to the duping by the acquaintance who didn’t follow through on his end of the charitable deal. Suing? No grounds. Asking for the money back from the opera? Pretty embarrassing, plus it punishes a charitable organization for a weasely donor’s duplicity. Gossip? Seriously? So, the answer, Klosterman says, is to call up the acquaintance and confront him by acknowledging that:

“This is no longer about chartity. This is about my relationship with you.”

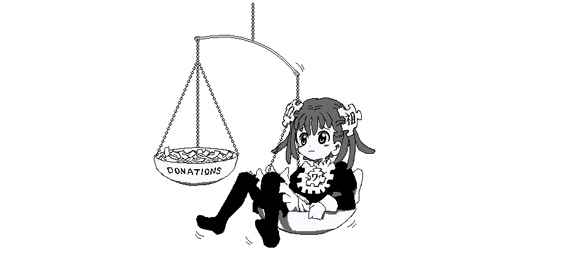

The entire scenario shines an illuminating light on the nature of art and culture patronage. One insight is Klosterman’s observation that the entire exchange never really had much to do with charity in the first place. Rather, cultural funding relies on a complex network of interpersonal exchanges related to sustaining societal and business interests. Non-profits are the beneficiaries of this social dance, but notice how quickly they can become innocent victims of the same scheme. When the patron discovers he or she has been duped, the first knee jerk reaction is to consider requesting the money back from the opera. The patron feels like a fool, and someone must pay. The feeling of personal scorn seeks financial recompense. And cultural institutions are often caught in the middle.

Image via