There are a number of historical and cultural questions that linger after viewing the Dallas Museum of Art’s new exhibition, The Legacy of the Plumed Serpent in Ancient Mexico, which includes art and artifacts largely from southern Mexico spanning a period roughly from 900 AD through the early colonial era. What was the ethic and cultural make up of this region? How did the rise of the Aztec population affect social-political circumstances? To what extent did these peoples, already colonized by the Aztecs, embrace – or withstand – the arrival of the Spanish?

Some of these things are touched upon in the DMA’s exhibition, and with a little time spent with some of the historical volumes scattered about the galleries on benches, as well as close attention to some of the objects in the exhibition (some of which offer pictorial histories, others evidence of an intermingling between the encroaching Christian influence and the traditional native arts), a visitor to Plumed Serpent could likely dig up answers. But that history remains somewhat obscured in the new exhibit is actually one of its virtues; rather, curators have taken care to arrange a series of exquisite works of art loosely connected by a recurring myth – the serpent – but more directly representative of a remarkable aesthetic sensibility and virtuosic craft.

The image of the Plumed Serpent comes from a myth of a ruler, Quetzalcoatl, expelled from the city of Tula, who then traveled through the south of what is present day Mexico and became revered by many of the cities as a patron-deity. That story became a kind of mythic glue that helped foster cultural and economic ties between the region that developed a particular aesthetic and cultural identity during the centuries before the rise of Aztecs.

The exhibition is organized in loose chronological fashion, with an attention in each to a particular medium. Individual objects show how the image of the serpent was represented and reinterpreted in a variety of media and local circumstances. A front room of clay pottery offers both meticulously balanced forms and vessels that incorporate figures expressing bold, effortless personality. In the second gallery that includes many effigies and sculptural representations of Quetzalcoatl, the floor is dominated by a large rectangular sculpture of a serpent. Its mammoth size is arresting, and there is something appealing and visceral about the long and smooth lines hewn from the massive stone. Many other objects in exhibit are adorned with figures and patterns built out of lax geometrics, quadrangles with rounded edges that become arms, legs, instruments, headwear, faces.

I could have spent the entire time in Plumed Serpent absorbed by a series mosaic discs, all roughly a foot in diameter and composed of miniscule shards of stone, shell, or turquoise. Rough geometric patterns create hieroglyphics or figures engaged in rituistic play. But it is the pure materiality of the objects that most moving. Some pair the mosaic with wood, or clay, or stone. One presents a series of warriors in a ivory white set against eggshell, a spinning, monochromatic grid that is reminiscent of Angus Martin. They are all breathtakingly delicate, supple, and beautiful.

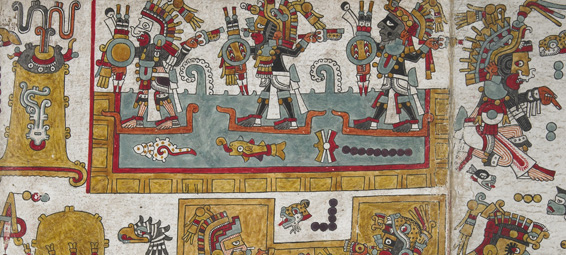

The centerpiece of the exhibition is also its most impressive piece, a codex, (Codex Nuttall) a diminutive bound book consisting of dozens of pages, each filled with colorful renderings of scenes that together tell a foreign history. An iPad near the object allows viewers to flip through and explore all of the book’s pages, and the object itself is opened to perhaps its most impressive spread, a blizzard of tiny, colorful figures comprising a series of historical vignettes. Hundreds of such codices like this once existed, but most were destroyed by the Spanish who saw them as dangerous pagan scripture. This particular codex is on loan from the British Museum, and it is thought to be one of only a handful to survive because it was included in the first cache of loot sent back to Spain by the conquistador Cortez after his arrival in the New World. That historical context adds a gravity to the work, which, in and of itself, is quieting.

Image at top: Codex Nuttall, Mexico,Western Oaxaca, Mixtec, 15th–16th century. Deerskin, gesso, and pigments. 44 11/16 x 7 1/2 x 9 1/4 in. (113.5 x 19 x 23.5 cm). Trustees of the British Museum, London(MSS 39671). Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum/Art Resource, NY