As the Dallas International Film Festival comes to a close, one of the highlights of the last weekend of the fest is the chance to see films that have won the festival’s various competitions. Stay tuned to the Dallas IFF schedule to find out what films will receieve repeat screenings. This weekend will also see the 25th anniversary of Robocop at the Texas Theater, as well as a screening of Precious with Gabourey Sidibe. And here are some of the other films playing at the festival this weekend:

FRIDAY

Liberal Arts (April 20 at 7 p.m. Angelika 6)

Rating: Worth A Shot

None of the stars of the second film by actor/director Josh Radnor, Liberal Arts, were able to make opening night’s screening, but producer Claude Dal Farra introduced the movie. It ended up fitting with the festival’s producer theme, Dal Farre sharing a story about how the enthusiastic and sincere Radnor pitched the film and the producer responded flattly, “Why do you want to make a feel good movie?”

Liberal Arts is, if nothing else, a feel good movie — sweet, cute, and warm — a romantic comedy best-served to under-35 significant others snuggled under blankets. It is also a vast improvement over Radnor’s debut, Happythankyoumoreplease, in the simple fact that Radnor has grown more comfortable with his comedic instinct, and he tones down his inclination to pick and poke at his character’s psyches with boiled-down psycho-jabber. Radnor plays Jesse, a 35-year-old university admissions counselor living in New York who is called back to his alma mater, a small college in rurual Ohio (the movie was shot on the campus of Kenyon College), for the retirement party of his favorite professor, Peter (Richard Jenkins). There he meets Zibby (Elizabeth Olsen), a pretty sophomore. Jesse and Zibby hit it off during the weekend, and before he returns to New York, Zibby gives him a classical music mix CD and invites him to write her the “old fashioned” way, that is, on paper. Back in New York, the music begins to impact Jesse’s life in whimsical, often hilarious ways, and the couple’s letter correspondence blossoms into a relationship.

What is most appealing about Liberal Arts is its softly nostalgic longing for the sweet simplicity and intellectual leisureliness of collegiate life. We are most affected not through the babbling about books and poets, but in quirky ways Radnor works their influence into mood and feel of the film, overlaying the classical tracks and personifying the unchecked cerbreality in the diametrically opposed personae of two of the movie’s most enjoyable characters, Nat (Zac Efron) and Prof. Judith Fairfield (Allison Janney). Nat is a stoner-ham, animated and spirited, speaking always in jarbled hippie-esse. Judith is a romantics professor whose been worn down by academia, becoming cold, cynical, and detached. We need both these characters inLiberal Arts to prevent Radnor from losing himself in what drowned his first movie, all the bromidic soap-boxing, in which all motivations, self-understandings, aspirations, and philosophies are hemmed-and-hawed, mumbled and jawed, with the same vainly self-conscious satisfaction of sporting a tweed jacket on a gear-less bicycle.

There’s some of that in Liberal Arts. Jenkins character is mostly reduced to kvetching, and, as in Happythankyoumoreplease, Radnor’s Jesse needs some poor soul to inexplicably need him. That’s where John Magaro’s mopey and pointless Dean comes in. But Olsen and Efron remain center stage. Olsen’s Zibby has a wry spunk, a knavish spirit which goes a long way towards making the cutesy, hug-y stuff bearable. And Efron’s natural sincerity is an aseet. His Jesse is accused of being too soft-hearted, and we come to think so much of him, but that’s the point. He’s the kind of guy who frets about age, not mortality; affection, not love. “Everything is going to be okay,” Nat tells Jesse, as if they were a duo washed-up in an AA meeting. And of course it is. There’s not that much at stake, and everyone has a good sense of humor. — Peter Simek

Elena (April 20 at 7:15 p.m. Angelika 7)

Rating: Go See It

A slow-building, strangely satisfying Russian film that tests and proves the maxim that blood is thicker than water. Middle-aged Elena is married to the wealthy Vladimir, whom she met when she was his nurse during a hospital stay 10 years earlier. She divides her time between Vladimir’s posh, pristine apartment and the crowded communist-bloc housing in which her son Sergei lives with his wife and two children. Though they are sometimes physically affectionate, Vladimir treats Elena more like his servant than his spouse. He resents being asked to help support the family of the lazy, shiftless Sergei even as he dotes upon his own ungrateful, hedonistic daughter. Elena loves Vladimir but is ultimately compelled to what feels like a revolutionary act of class warfare. — Jason Heid

Alps (April 20 at 7:30 p.m. Angelika 8)

Rating: Go See It

Alps, the latest film from Academy Award-nominated Greek director Giorgos Lanthimos (Dogtooth), is a parable of estrangement, submerged in the director’s characteristic Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt, the camera and characters obscured in a difficult and alienating pictorial world. Aggeliki Papoulia plays a member of a small team that calls themselves “Alps,” and they offer a strange service to people who are grieving the loss of a loved one: pay-for role play. Each character takes on the part of a deceased lover or family member, acting out staged scenes seemingly to fill the void or the silence that accentuates the onset of grief.

Lanthimos’s films deliberately subvert dramatic and emotional feeling, creating anti-melodramas that are nonetheless caught up in a profoundly devastating dramatic arc. We never really get to know anyone as we are used to “knowing” characters in cinema, instead each personae operates in a world that is robotic and oppressive. There is an undertone of physical and emotional abuse; the two males in the foursome that make up “Alps” are chauvinistic, brutal, and totalitarian. The women are strangely obsessive about their desire to submerge themselves in their fictional personae, and as the film progresses, it becomes clearer that they themselves are lost to the layering of roles and role playing.

What is remarkable about Lanthimos’ films is that even though they are structured to alienate the audience from the characters and their world, there is a slow erosion of feeling that takes place as a result of his deliberate and lumbering style. Shots are excruciatingly long, as are the many uncomfortable settings, and humor is achieved through a recognition of the pure absurdity of the drama. In one scene, Papoulia’s character acts out a scene with a man in which she pretends to break up with him and move to Toronto, over and over. The scene is in English, and the language is stilted and insufferably staged. It is impossible not to laugh, but there is something truly heart wrenching and surprisingly honest about it all.

There is a temptation among critics when writing about Greek art to carelessly toss around the word “tragedy,” but with Lanthimos there seems to be a working through of the structure and effect of tragedy, mingled with a very modern approach to obscuring pathos. It makes for a very difficult movie (and a number of people worked out of the Dallas IFF screening), but if you give yourself over to Lanthimos, you can’t help but find yourself deeply affected by a palpable and true-feeling desperation. – Peter Simek

Under African Skies (April 20 at 10 p.m. Angelika 6)

Under African Skies (April 20 at 10 p.m. Angelika 6)

Rating: Go See It

Paul Simon’s Graceland album has become such a ubiquitous part of American musical culture that it is difficult to place it back in the context of its creation. That’s what filmmaker Joe Berlinger tries to do with his documentary, Under African Skies. To shirk Behind the Music convention, Berlinger roots his music doc in the political conflict which played out around Simon’s album. South Africa is suffering Apartheid as Simon makes his way to record with South African musicians in 1985, violating a United Nations cultural boycott. In the movie, Simon sits down with Dali Tambo, a founder of Artists Against Apartheid and a critic of Simon’s work on Graceland, to retell the story from their conflicting perspectives. The result is a recapped version of the tense historical situation alongside studio shots with the Boyoyo Boys, the “discovery” of Ladysmith Black Mumbazo, and some notes on Simon’s completion of the album inNew York.

Ultimately Under African Skies strives to paint Graceland as a celebration of how art can transcend specific political environments, but Berlinger’s movie feels incomplete in that his championing of the artist glosses over some of the controversy surrounding the creation of the art. For example, while the doc touches on some of the controversy over Simon’s songwriting credits – and thus royalty control – on Graceland, much is left omitted. Paul Simon still gets full credit for “You Can Call Me” Al, even though the documentary clearly shows an African guitarist originating the song’s signature riff. And completely missing from the conversation are some of the non-African studio musicians, such as King Crimson’s Adrian Belew and Los Lobos, who have publically quarreled with Simon over songwriting credits. Ignoring all this – and likely more – left Under African Skies feeling enjoyable, but incomplete. — Peter Simek

I Wish (April 20 at 10:15 p.m. Angelika 7)

Rating: Go See It

Two young boys are separated when their parents’ marriage falls apart in Japanese director Hirokazu Koreeda’s beautiful new film, I Wish. One ends up with his mother and grandparents, living in a sleepy town that is towered-over by an ever-erupting, ash-spewing volcano. The other lives with his father, the front man of a modestly popular, but by no means successful rock band. Apart, the older boy, Goichi Oosako, is sad and withdrawn, while his cheerful, amenable brother, Ryoonosuke Kinami, adjusts to his life alone, finding a group of girls for playmates. When Oosako learns about a local legend that claims that seeing two bullet trains passing each other will grant a wish, he and his friends begin raising money for a trip that will lead them to the miraculous passing. Soon both brothers and their cohorts are off on a childhood-defining road adventure.

“The world needs wasteful things,” the boys’ father says at one point. “What if everything in the world was full of meaning?” That question seems to guide Koreeda’s meandering, documentary-like style that revels in the small details – from cakes and ash, to the human touch – creating wistful passages that infuse the story with an infectious sentimentality. There is a sweetness to the shape of life in I Wish, and what convinces us is Koreeda’s ability to shoot the film through children’s eyes, patient and observant, clouding out the loss and loneliness that linger on the periphery of the story. There is something undeniable about watching an older woman stroke the hair of a young girl, remembering her own lost daughter, or seeing a group of children climb a hill baring a white flat that lists their lives’ wishes, scribbled out in marker. For Koreeda, hope is rooted in the possibility of beauty, and the director manages to capture heaps of it. — Peter Simek

SATURDAY

Bonsai (April 21 at 4:30 p.m. at The Texas Theatre)

Rating: Go See It

(Prior to Bonsai’s screening, there’s a short, The Birth of Saint Eliseo. It’s about 15 minutes long, ham-fisted with its message, and otherwise not very good. What I’m saying is if you’re 15 minutes late to Bonsai, don’t worry.)

At the intersection of Proust, punk, and first love, Bonsai welcomes the viewer to an experimental experience, one where art imitates life, even when the art being created doesn’t know those events have happened. The story centers on Julio and Emilia, young lovers whose relationship begins when Julio lies about reading “Remembrance of Things Past.” The 90 minutes that follow are full of the interweaving tales of the young couple, their eventual break-up, and Emilia’s eventual death. That’s not giving anything away; a narrator spells it out in the first frame of the film.

Written and directed by Chilean Cristian Jimenez, Bonsai takes an unpretentious look at a pretentious relationship, relying on coy cutaways and dialogue to tell the disjointed story of Julio and Emilia. In the end, the audience knows what’s best for both of them, even if they can’t see it.

No Ashes No Phoenix (April 21 at 5:30 p.m. Angelika 8)

No Ashes No Phoenix (April 21 at 5:30 p.m. Angelika 8)

Rating: Worth a Shot

A documentary about a German professional basketball team, freshly promoted to the country’s premier league, struggling to avoid a finish at the bottom of the standings. After a series of lopsided losses, the Hagen Phoenix obtain star player Michael Jordan (no, not that Michael Jordan) to improve its roster. Instead they learn how destructive an outsized, self-obsessed personality can be to a locker room. As the Phoenix fight to avoid relegation to a second-tier league, we don’t hear enough about the motivations of the individual American and German players and coaches. Are they seeking a long-shot launching pad to the NBA, or are they just happy to be playing the game anywhere? The movie isn’t concerned. Still, No Ashes, No Phoenix was worth watching just to learn the delightful fact that there’s a German pro team whose mascot is the “New Yorker Phantoms.” — Jason Heid

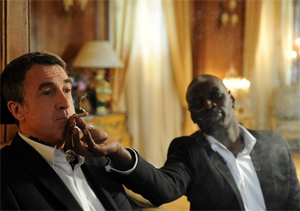

Intouchables (Apr. 21 at 10:15 p.m. Angelika 7)

Rating: Go See It

Intouchables is a cultural phenomenon in France, raking in $312 million in Europe and being named the cultural event of 2011 by 52 percent of the country. In America, I had never heard of it. When I walked out of the theater Saturday afternoon, though, I knew I had seen the best film of the festival. Is it sappy? A bit, but it balances that with enough wit and warmth to keep the viewer from groaning.

Intouchables is the story of Philippe, a wealthy quadriplegic, and Driss, his unlikely Senegalese caretaker. Philippe teaches Driss about Chopin, Driss teaches Philippe about Kool and the Gang. They smoke weed together, and Philippe cons one of his rich friends into buying Driss’s terrible painting. It’s a comedy, but one with considerable depth of character and plot. If you see one movie for the rest of the festival, make this the one. –Bradford Pearson

SUNDAY

5 Broken Cameras (April 22 at 3:15 p.m. Angelika 7)

Rating: Go See It

5 Broken Cameras, a documentary shot by a Palestinian father living in the tiny West Bank town of Bil’in, is the kind of film I would normally expect to see at the Dallas Video Festival. It is strikingly astute, exasperating, uncompromising, and difficult. It is also a product of citizen journalism, a film made possible by the increasing accessibility of the art of the moving image to the everyman. As a result, it offers an unfettered, unmediated, and unforgettable perspective into the Palestinian-Israeli conflict

The filmmaker is Emad Burnat, who lives in Bil’in, a Palestinian village that in 2005 began a nonviolent resistance of Israeli settlements in the West Bank which were being constructed on village land, the olive groves sustain the Palestinian villagers. Emad purchases his first video camera around that time, after his fourth son is born, and one of the narrative threads running through the film is watching his boy grow up amidst the protests and eventual violence that engulf Bil’in. Emad captures the increasing encroachment of the settlements and the escalating aggression of the Israeli army, which fires rubber bullets, tear gas, and sometimes live ammunition at the protesters, mostly men, but also women and children. Over the course of six years, five of Emad’s cameras are broken, which becomes another way of marking the impact of the conflict on his person and family.

5 Broken Camera’s strength is its honesty, which it derives through the soft-spoken, appealing personality of Emad. He is, like his film, devoid of ideology, and his documentary lends a humanity and sensitivity to the Palestine people that feels rare. The most shocking moments in 5 Broken Cameras are those that show the vicious, unprovoked brutality on the part of the Israeli army. Horrifyingly, in one moment we see one of the beloved villagers shot. He dies, right there on the screen, which is a moment both terrifyingly gruesome, but also necessary. Video is a mediation between the viewer and reality, and Emad even admits to using his filmmaking as a way of shielding himself from what is taking place around him. But there is no way to really empathize with what is happening with Bil’in without feeling the blunt impact of death. It is a moment that drives home 5 Broken Camera’s real message: what the news cycle misses in its jabbering over politics and events is what is really at stake in the West Bank: the life and death of the innocent. — Peter Simek

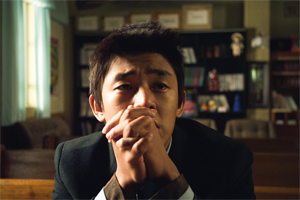

Punch (April 22 at 3:30 p.m Angelika 8)

Rating: Go See It

When I left Punch, I immediately called my mother to tell her I loved her. The movie’s the story of a poor, angry Korean boy with a hunchbacked, tap-dancing father, a non-existent mother, and a verbally abusive teacher who lives next door. If the pope was involved, it would sounds like the set-up of a life raft joke.

How those four people — and those around them — become a family, forgetting the past and looking to the future, is the crux of the film. The son, Wan-deuk, is a poor student, prone to violent fits and skipping school. His father, the hunchback, tap-dances on the street. The tenderness of their relationship, despite the circumstances, buoys an otherwise average film, making it worthwhile. It will make you want to call your mom, I hope. – Bradford Pearson

Where Do We Go Now? (April 22 at 5:15 p.m. Angelika 7)

Rating: Worth A Shot

Lebanese actress and director Nadine Labaki’s new movie, Where Do We Go Now? opens on a wide open plain, a group of women dressed in black singing and dancing in unison, as if they were taking part in a staged funeral procession. It is an image that encapsulates the mood of film, which is caught-up in the anxieties of conflict and the feminine consern for the preservation of generations.

Despite the decidedly dour scene, Where Do We Go Now? is an off-beat, quirky comedy. Taking place in a remote Lebanese village, tensions rise between the once-peaceful Christian and Muslim populations as a series of mishaps and misunderstandings introduce religious tension to a town that has miraculously avoided the decades of violence that has ravaged the rest of Lebenon. Labaki waves a finger at television. The young men of the village set up a community TV, and both the news broadcasts and mishaps during their efforts to secure a good signal fuel the growing conflict. To resolve the situation, the women — both Christian and Muslim — cycle through a series of Lysistrata-inspired remedies, including paying a local pimp to bring by his Ukrainian dancers. A sudden death of a young villager, however, poses a seemingly insurmountable obstacle to peace.

Something about Where Do We Go Now?‘s off-kilter humor didn’t quite register with this viewer, which made the film feel a bit tedious at times. But I’m obviously a minority. The movie took home the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival, as well as Un Certain Regard honors at Cannes 2011. There is much to enjoy about the movie, which lends a welcomed tongue-in-the-cheek to the high-tragic themes of the Middle East, advocating for a bit of bawd and booze in the wake of high-minded — and high-stakes — righteousness.

Quick (April 22 at 6:30 p.m. Angelika 8)

Rating: Don’t Bother

In the pre-festival literature, Quick is described as being “made in the spirit of American action movies Speed and Crank.” And while that’s true, audiences would be better off buying editing equipment, renting Speed andCrank, and splicing the two films together. Quick, for all its explosions and motorcycle chases, is boring in its delivery, spending too much time putting its characters from scenario to scenario, and not enough time developing why they’re there in the first place.

Like Speed, a man and a woman have been co-opted by a homicidal maniac, who’s rigged the two of them with bombs. Like Crank, some of this takes place on a motorcycle. The influence is palpable. But while Speed and Crankare tongue-in-cheek funny — “Harry, there’s enough C-4 on this thing to put a hole in the world!” — Quick honestly thinks of itself as a humorous film. The fat detective in charge of the investigation is a bumbling dullard, the butt of all the jokes. Maybe something is lost in translation, but I didn’t laugh once. There are sure to be plenty of other films in the South Korean Spotlight showcase worth your money. Quick is not one of them. – Bradford Pearson