The stories that make up Eric Steele’s The Midwest Trilogy are threaded together by setting and staging, the three-part tale told in film and theater in Bryant Hall on the Kalita Humphreys campus. The black box has undergone an amazing transformation from theater to soulless hotel conference room. The nondescript room, wall-to-wall carpet adorned with metal, straight-back chairs and a short, elevated stage area, underlies the Trilogy’s conceit: that good, wholesome folks from Iowa and Kansas are interesting because, at first glance, they seem so contentedly bland.

Something dark, or at least something raw and human, must lurk below the lily-white surface. We are first introduced to Steele’s vision of the American Heartland via two short films, Cork’s Cattelbaron and Topeka, before actor Barry Nash performs the one-man play, Bob Birdnow and the Remarkable Tale of Human Survival and Transcendence of Self. All three mine the tendency to disparage the spirit of the milquetoast Midwest by forcing these plain folk into highly dramatic situations. The mystery, supposedly, is that the characters react in ways we don’t expect. As we enter the hotel conference room, we are asked to write our names with a Sharpie on a “Hello, My Name Is” sticky tag. We sit in one of those straight-back chairs, immersed in what is a sort of cultural stereotype sales conference, where we’re spoon-fed bits of knowledge about the dangers of underestimating people of moderate temperament. You never know what they’re capable of.

The first installment in the trilogy, Cork’s Cattlebaron, features an incredible performance from the mercurial, silver-tongued Robert Longstreet, who plays a cocky, chatty road warrior salesman showing off at a steak dinner for a younger salesman. The short is powered by a sudden reversal of fate, which we see coming, but thanks to Longstreet, it is still painful. The second film, Topeka, was a disappointment. The short was Steele’s first, and it shows. The themes—feeling, sounding, and looking foreign; corporate politics; wrong-headed assumptions; opaque motivations—are similar to Cattlebaron, but the reversal here is trite and it undermines the path we took to get there. It’s the directorial tone that feels off, a persistently ominous, American Gothic strangeness that seems to push the audience to make the same wrong assumptions about the small town folk the short’s main character does. The reversal loses its bite because we’ve felt coerced into an underestimation all along.

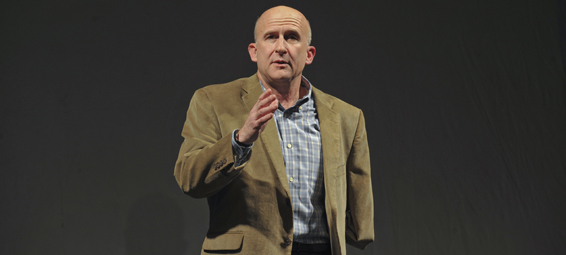

The best of the three pieces is rightly saved for last, Bob Birdnow and the Remarkable Tale of Human Survival and Transcendence of Self, directed by Lee Trull. The title character, Bob Birdnow, played with exacting care by Barry Nash, is a man whose intense outward ordinariness (with a couple glaring physical exceptions) belies the horrific tale he delivers to us in meandering monologue form, under the guise of “non-motivational” speaker. Nash inhabits this simple man in wonderful detail, and Steele has a way with words. One distraction comes from Birdnow’s two trips to the back of the room for a drink, a trick that is intended to lend movement to the piece that it doesn’t really need. Sure, there’s no set, but the pictures are painted clearly enough in the play’s language; the coffee, or whatever Birdnow fetches, could have just as easily been on stage.

The problem with Birdnow, however, is similar to the two short films. We already have a vague idea of what will happen in this story, so by the time Birdnow gets around to telling us exactly what unfolds, the emotional impact comes not from the surprise, but from the weight of an explicitly gruesome description. The relationships, the people he’s mentioned in the telling of his life story, are just narrative props. Every time he circles back or repeats himself (perhaps on the pretense that he doesn’t actually want to tell his real story), restlessness sets in. There are moments where it does truly feel like we’re making the best of a mandatory work function. There are parts you perk up to listen to; other times, you can let your heavy, tired eyes close—just for a second. At the end there is poignant silence, and then noise. What Birdnow achieves is not quite the promised transcendence, but it is something nonetheless intimate and heartfelt.