I visited two shows last week that, by total coincidence, were each composite self-portraits of the respective artists: Michael Bise at Fort Worth Contemporary Arts in a show called Epilogues, and Michelle Rawlings at Oliver Francis Gallery in one called Empathicalism. The first was a wry, deeply thoughtful and searing look at a private life lived with the constant threat of death; the second was a self-dissecting, self-deprecating mash-up by someone who’s maybe never had anything to be afraid of and hates it.

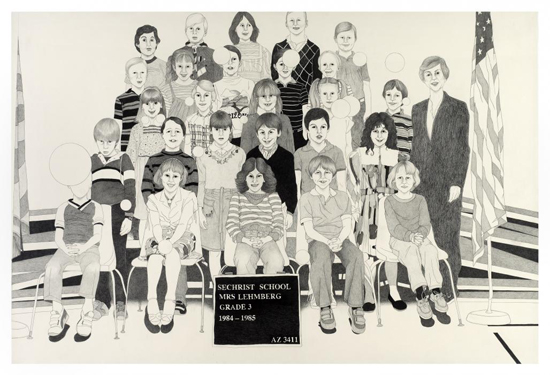

Michael Bise’s huge graphite drawings on paper depict domestic interiors cluttered with kitsch figurines and portraits of Jesus, grade school pictures, and fervor-filled evangelical moments that drip with perverse hedonism. There is also a series of Bise’s smaller, comic-style drawings called Life on the List, that he made recently for Glasstire, which chronicle the artist’s struggle to come to grips with his perhaps imminent death as he waits for a heart transplant (which, thankfully, Bise received a few weeks ago).

Bise’s pictures are sophisticatedly rendered. There’s a photographic quality to them, in the spirit of Chuck Close, but then they are also rooted in a 1980s retro sensibility that palpably conveys the feeling of being a kid in a wood-paneled room where you’re trapped with grownups that are all smoking cigarettes. You want to cough, but it might come across as disrespectful.

Through his confident and dense mark-making that remembers cartoons, snapshots and television, Bise captures that ineffable aura of childhood, with all its confines and lead-black limits.

Apart from Bise being an incredible draftsman, he’s also an incredibly astute cultural critic; what he condenses in a single image is enough sociological fodder to chew on for a long, long time. Take, for example, the piece called Revival which depicts a swelling bevy of females in a tent, all swaying and contorted in ecstasy as they ostensibly revive their commitment to Jesus. The picture is tremendously big – over 84” wide and every inch of it filled with flawlessly described characters of all types: the young and old, the beautiful and mangy, fat, skinny, tall, short, fashionable or homely. And almost every last one is closing her eyes. More than the picture describes any sort of sanctification, it depicts a sort of bacchanalian frenzy that looks more painful than it does, er, reviving. Robert Longo’s spasmatic suited men and women come to mind; so does Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (the hell part). What we’re witnessing in Bise’s Revival — as indicated by the lone woman with her eyes open, staring at the mayhem – is a kind of spiritual mob mentality. It’s a pressure-filled space, replete with artificial and genuine fervor, and, more than anything, committed showmanship. Separating the chaff from the wheat, let’s say – the real believers from the phony ones — would be a doozy of a task. Bise chooses to essentially damn them all, and, through proxy, so do we.

Admittedly, seeing Michelle Rawlings’ show right after Bise’s skewed my perceptions a little. It was jarring to go from the quiet, wide FWCA gallery, where visitors were humbled a bit by Bise’s candid but deeply witty portrayal of his life and struggles, to the small space of Oliver Francis Gallery where the artist’s well-heeled friends and relations (not to mention a security contingent – Rawlings is daughter of Mike Rawlings, the mayor of Dallas) were crammed shoulder to shoulder noshing cheese cubes. Outside, the mayor had hired a valet service, which had the neighborhood dogs barking as runners ran to and fro fetching Porches. I knew going into it that all of this veneer was really part of the show – that the artist and the gallery itself had orchestrated the extra stuff to up the ante on the art work, which, compared to Bise’s, was an autobiographical horse of a different color.

Where Bise chooses to tell his story though visual narratives and vignettes that strike at the art of being alive, Rawlings has parceled out her life here in the gallery with visual cues and self-effacing jabs, in all manner of media—video, painting, and installation-ish accents — that describe a young woman coming to grips not with the eternals so much as the surface of everything – the titles, the accolades, the body parts, and the accoutrements of privilege, with all the stereotypes that come with it. Rawlings is using herself as a whipping boy (girl?) upon which the lower classes may strike with all their judgments: spoiled brat, pretty girl, cheerleader, daddy’s girl, etc.

That Rawlings is a lovely blonde that may, in fact, be all of the things above is entirely the point. We’re supposed to hate her a little and want her all the same, as the painting of naked female genitalia (hers, I presume) that hangs front and center in the gallery and is guarded by red velvet curtains and indoor houseplants (palm trees) suggests. You hate her for her securities, but you praise her for the fact that she’s confident enough to hang them all out like wet (but really clean) laundry.

There is a tapestry here embroidered with Rawlings high school yearbook picture, her selected quotes from the yearbook by people like Van Morrison, and her stats – sports she was involved in, awards she won — as well as some cute pictures of her as kid. To the left of the tapestry is a diagonal line of five small paintings with smiley-faced crosses painted in a naïve, outsider-artist style. There is also, among other things, a video of the artist in a Nativity play as a kid. The camera zooms in and out, its focus always on Rawlings.

The wholesomeness that Rawlings is mocking herself for – her Christian, school-girl regularness and her life as the art-student daughter of a third-tier city’s mayor (and the former CEO of Pizza Hut) — is clearly that artistic “thing” that preoccupies her. I gather she’s never quite felt comfortable in the role, and it’s clear she’s working out what that means and who it makes her. She can’t very well “un-be” any of it, just like Tracy Emin and Sara Lucas, conversely, couldn’t undo their blue-collar, sordid pasts. But there’s something wanting in Rawlings work, something a bit more unhinged or revolting; or something more elegant and studious. Either way, Rawlings is learning how to tell the truth about herself. Her work here at Oliver Francis is a start down what will be, I suspect, a long road toward real discovery. But for the time, like Emin and Lucas before her — and Cindy Sherman, for that matter, Rawlings is laying everything about herself out on table, though perhaps without the poetry and suffered insight of those other women. But, if Rawlings is serious about wanting to unpack her life as an artist, that will be suffering enough to steer her in more fecund and honest directions. This show here, as I say, is a good place to start, and an even better point of departure.

Image at top: Michael Bise, Revival, 2009. (detail) graphite on paper; 41 1/2″ x 84 1/4″ (Courtesy Moody Gallery)