This Sunday, the artist Christo will speak at the Nasher Sculpture Center as the keynote speaker of the Dallas Design Symposium. Reprinted below is a transcript of a telephone conversation I was able to have with the artist thanks to the Nasher. It is a half-hour conversation reproduced largely in its entirety. While the sheer length of the piece may feel prohibitive to reading online, I am including it all because this writer happens to believe that there are few artists whose work and aesthetic philosophy can offer as valuable an insight into how we understand Dallas — its culture, its space, and society — as Jeanne-Claude and Christo.

In our conversation, Christo speaks of order and disturbances: the freedom of art when it exists outside of corporate, institutional, or gallery contexts. The art of Christo and his long-time partner and collaborator, the late-Jeanne-Claude, are (and note how the artist insists on referring to his temporary projects in the present tense) objects, experiences, and stories, requiring conversations with the agents of political order in order to achieve through them an expression of irrational, unnecessary aesthetic ordering. It is this futility of art, its practical incongruence, that Christo asserts is art’s greatest quality, its essential freedom. The artists, through their life and work, offer warning and encouragement: to not allow art to be co-opted by a rationale that seeks to justify art along economic, social, or political lines. We need to be wary of propaganda in all its various forms — economic, social, political, religious, etc. — even in a society without government-sanctioned propaganda. We need to remember that art’s uselessness is not only a characteristic of its freedom, it is evidence that freedom itself actually exists.

I hope you will defy the conventions of the Internet, and read this long piece.

How do your projects originate? Is there a foundational idea?

First thing. We are working simultaneously at several different projects. Jeanne-Claude and myself, we realized 22 projects, and we failed to get permission for 37. Now, understand that the project involves many things, but before everything, this project is initiated by us. We do not do commissions, not like architects; we don’t build buildings. It is all projects initiated by us, and each project has its own history, its own secret. I can tell you one or two, but they are long. And I always say that the biggest, the most complex period of our projects — we often call it the “software” period — it is when the project is in the permitting process, because all of our work is a unique proposition, meaning that we will never build another Gates, we will never surround another island, we will never wrap another parliament. They are completely new images; there is no precedent for our project. Through the permitting process the work of art develops its own identity. When we start a project, we have the slightest idea what the project is. Of course aesthetically or formally we have some idea, but even that is very simplistic and very minimal, simple. Through the permitting process we know more about the space, the land, the people, everything, and all that becomes part of the work of art.

So when a project like The Gates or the Wrapped Reichstag began, what did it look like in the studio?

Let’s take The Gates because they are two different projects. We do projects that are in an urban space and a rural space. But always on those two sides, the human scale is present. Even in the countryside, when we do projects, not only for pure philosophical ideas but also for aesthetical importance, it always needs to be compared to some manmade elements: telephone pole, house, bridge, roadway, etc. This is on the rural side. On the urban side it is much more obvious, and The Gates project was an urban project. Each project has its own starting point. When I immigrated to the United States — it’s a very long story, but you asked me about The Gates, and I need to tell you. We come to the United States in 1964, myself and Jeanne-Claude. We say we didn’t immigrate to the United States, we immigrated to New York City and especially to Manhattan. We’ve lived in the same building since 1964. Now, we came by ship from Europe, and the skyline of Manhattan made the most important impression to us. The first proposal to do something in New York City was to wrap two lower Manhattan buildings in 1964. We never got permission. The second was in 1968 we tried to wrap No. 1 Times Square, which at that time belonged to Allied Chemical Corporation. We never got permission.

Now, to the ’70s. We spent a lot of time in the West. We did Valley Curtain in Colorado in 1972. We did the Running Fence project in Northern California between 1972 and 76. Coming back from the west to New York all the time, myself and Jeanne-Claude, we saw that one of the most fascinating elements of New York City is not the skyline, but the humans – especially the people and the people walking. Manhattan is one of the great walking spaces, and you have like a river of people walking. We were contemplating in the 70s to use the sidewalks. The problem was we would never get permission to use the sidewalks. So the place where people walk leisurely is in the parks. And one park that was entirely cut from any natural form is Central Park. Central Park is framed by hundreds of city blocks all around. It is an entirely manmade park. Everything was brought there. And, of course, the process of walking is also very manipulated by the architects. In Central Park, unlike the Hyde Park in London, where you can walk anywhere, in Central Park you are surrounded with stone walls and there are several openings, and these openings are called “gates.” And actually, they really planned in the 19th century to install steel gates to close the park in the evening. They never did do that.

We decided to take that very elaborate, very intricate walkway system to energize the most invisible space — between your feet and the first branches of the trees. That space we never actually think about. And we needed to create some kind of order in that space. The walkway system is designed with a very serpentine quality, and this is why we would like to find a module which would reflect how Central Park is situated in Manhattan. This is why we do not do arches. We build gates because the gates reflect the footprint of all the city blocks, that rectangular shape of all the city blocks around Central Park, a very geometric shape. The fabric attached to the horizontal part of our gates — moving in all directions — reflected the serpentine character of the walkway system and, of course, the naked branches of the trees during the winter time: that contrast between the organic and the geometric shape is embodied in 7,503 gates. They are always 16 feet tall, but the width of the gate varied from 6 feet to 18 feet wide. They’re very invitational. They are only 12 feet apart, and you are invited to go to the next. And when the fabric, when the wind is not strong, you can touch it with your hand. There are a lot of inviting or teasing elements to touch that soft, very colorful, and very transparent fabric.

Now we chose the winter. In all our projects, they are seasonal projects. The Surrounded Islands project in 1983 in Florida (we surrounded the islands with pink floating fabric in Biscayne Bay in Florida) was a spring project before the hurricanes. The Central Park is a winter project because with the leafless trees you can see the gates. The project is very intimate, and it would always contrast with the skyline, with architecture, without imposing big tall structure in Manhattan. This is why we decided to do The Gates and not wrapping a tall building in Manhattan. Each project has its own story.

You mentioned introducing order to the space . . .

Not order — to energize the space between you and the first branches of the trees. That space is open, it is blank. It is a vista, but you don’t physically experience because it is empty; it is nothing. And suddenly by creating that structure which is really repetitious — every 12 feet going up and up.

We are doing projects that are outside of the normal museum space or protected gallery space, or space of the corporate collection, and everywhere art is usually experienced. It is a very antiseptic space organized by the artist. And this can be very classical sculpture, it can be very modern and all that, but that space is very antiseptic — artists control that space and do everything in his way or her way. What we are doing is working with other space that you very rarely think about. The moment you walk out of your home you start to walk on the sidewalk, somebody designed this sidewalk. You cross the street; somebody designed this red and green light. You take your car, actually you follow the 24 hours around the clock with lots of jurisdiction, lots of order, we don’t think about, but it is there in that space. So we try to borrow that space and create gentle disturbances for a few days.

By borrowing that space, we inherit everything that is inherent in that space to become part of the work of art. We do not invent ecology in Biscayne Bay in Florida. It was in the bay in Florida. It is a real bay. It is not the photograph of the bay; it is not a drawing of the bay; it is not the film of the bay. In a sense, all our projects deal with the real things, not imagery. Imagery art is illustration; it is not the real thing. And so when we take the Reichstag — which is another long story — we inherit everything which was in the Reichstag to become part of the work of art. And of course with Central Park we inherit everything that Central Park is in the mind of the New Yorker, in the minds of millions of people around the world. This is why it takes us 26 years for us to get permission in Central Park. There was one refusal in 1981, and in the Reichstag we have three refusals: in 1977, 1981, and 1987. Finally we realized it in 1995.

Is the permitting process important to final work of art? Is it important that your projects have to go through such a long process of realization?

The permitting process creates the identity of the work of art: this enormous dynamic that we do not know. The real permission of the Reichstag created a unique story in the history of art. For example, it was the first time in the history of art that the existence of the work of art was decided in the parliament of a nation, Germany; it was televised to 200 million people in Europe. We defeated the prime minister of Germany, Mr. Kohl, who was deadly against the wrapping of the Reichstag. Of course, all that makes the project a hundred times more important. And this is why each of our projects benefits from that enormous, great period of the permitting process. And that’s why I always say for every artist, the only aim is that people are thinking about his project, his painting or his sculpture — whether liking it or disliking — this is the most important thing. Every artist would like his painting or her painting to be discussed. And we’re probably the only artist that before the work of art actually exists, it is discussed by thousands, sometimes millions of people before it physically exists. There is some great pleasure and reward to see that we can create so much controversy before it exists. To make people think about something that does not exist.

Tell me how you and Jeanne-Claude began working together. Your first project involved wrapping cargo . . .

The first project was in 1961. In Cologne, I have a one person exhibition in a gallery, a normal small little gallery near the Cologne harbor in Germany. That gallery had a two show windows, and in the inside I had a wrapped automobile and large packages and other piles, but the gallery opened and closed, and we were very eager that we do something outside. And for the first time we go to the port authority of the Rhine River to ask them to allow us to wrap with very heavy tarpaulin merchandise at the port authority. This was exhibited for a few days as a temporary installation, and people could see the work of ours outside of the gallery. It is also the first time we asked permission to let us do that. And after that was Rideau de Fer the Rue Visconti in Paris, The Iron Curtain, which was a response to the Berlin Wall, which was just built in 1961 and our project was realized in June of 1962 in Paris.

How have you found working since Jeanne-Claude passed?

I met Jeanne-Claude in 1958 when I was 23 years old – both of us — and we were in love and we started to work together, just simply. And all our life. I lived with Jeanne-Claude for over 50 years. One of the most important parts was that she was a very critical person, argumentative and extremely critical of everything, and this is one of the greatest things I miss. She was very critical, and that is something artists need all the time. Sometimes it was my vision, sometimes it was her vision. For example, Surrounded Islands in Florida was her vision.

Also, we cannot decide our project in the studio. This is why for all our projects we do tests, somewhere in a secret place we can install not the entire project, but on a scale of one-to-one a big section of the project. And we decide what color, what kind of fabric, what steel, what form – all these things cannot be decided in the studio. That’s why each of our projects has a life size test. For The Gates project, for example, when we finally – there were two life size tests. One was in 1980. We were hoping to do it in 1981, and one in 2002 just before we get the permission in 2003. At our chief project engineer’s home, who has a home outside of Seattle, we had asphalt paths and built eighteen gates and all different type of fabric, different type of extra fabric, different type of feel – all variety of things. And those eighteen gates stayed for seven months, and you could see them in the wind and in the snow and in the rain and in the sun and choose the right color. The same thing we did with The Umbrellas, the same thing with the Reichstag. The same thing we did with Over the River – the next project. And in the color slides of the presentation in Dallas, I will show a few of the color slides of the real life size test.

Are you thinking about new projects now that Jeanne Claude has passed?

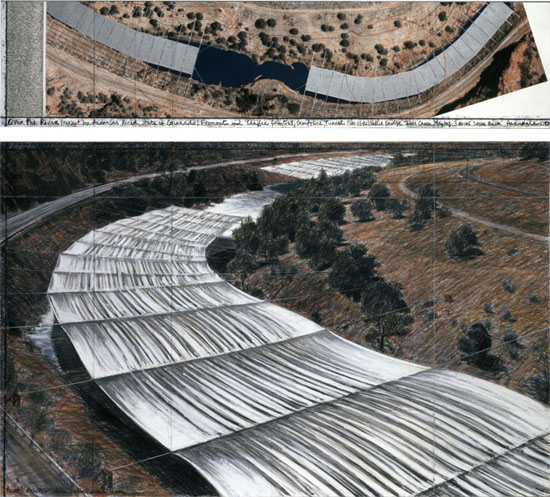

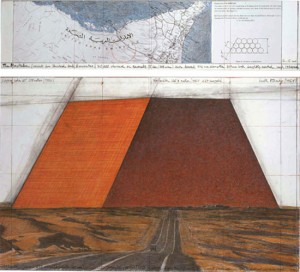

At the moment we have two projects. They are so advanced. Once one project has advanced permit wise, which is the case now with Over the River, and that project has taken eighteen years, and not because of the permitting was so difficult, but because we stopped to work on Over the River when we got permission on the Reichstag, which was finished in 1995. And we started again working on Over the River in 1996 and we stopped again when we got permission for The Gates in 2000, and we finished The Gates. And we invested so much effort so much knowledge and so much advancing in the permitting process, that we are now in the very last three or four months for the decision for the federal government because the decision involves the Bureau of Land Management and the Department of Interior and many other things which I will explain in the lecture. That project is slated for exhibition for two weeks starting in the month of August because we need to have rafters to see the project from the inside. It takes one and a half hours to see the project from above – it is forty-two miles long – and it takes about four-and-a-half hours to raft it. The project will be above you between eight feet from the water to sometimes ten to fifteen feet above you. And there is The Mastaba in the United Arab Emirates. So this is a huge amounts of projects.

Does it become easier to get permission for the projects now that you have had many highly successful, high profile projects?

Not at all. I can tell you we spent eight million on Over the River and we do not have permission.

You fund all your projects, and you won’t accept grants, let alone commissions. Why is that?

The freedom. To have this incredible pleasure to do what you like to do. All our projects are about freedom. Total freedom. The way we like to do it – aesthetically and everything. And of course there is great pleasure – Jeanne-Claude always was saying we do our project for ourselves first, and if people like it, it is a bonus. They are no strings attached presents. They exist not because some museum wants it or some corporate executive or some arts grants, congressional assent – not at all. The projects are totally irrational, absolutely unnecessary. Free of everything. You know, I escaped from a communist country, and I am allergic to any art related to propaganda. And everything: commercial propaganda, political propaganda, religious propaganda – it is all about propaganda. And the greatness of art, like poetry or music, is that it is totally unnecessary. Because we are surrounded by a world that stifles our existence, we work better. There is this enormous creativity that humans can do.

You are in a position to self-fund your projects, but many young artists are not. What would you tell them – do you have recommendations, encouragement, advice?

Who are we to give advice? Every human has his own life and her life, and it is a very private thing. And this is so important because this is probably one of the greatest luxuries that humans have: that they have a life. But of course for the young people who like to do art, they should work on their art. I never take a vacation; I work all my life because art is our life. And if you work all the time with no diversion, you will do what you like to do. The biggest problem is to know what you like to do. And often the young artists they do not know. They are all dispersed, do too many things. I don’t know. You need to be extremely focused.

Main image: Christo, Over The River, Project For Arkansas River, Colorado. Drawing 2010 in two parts: 38 x 165 cm and 166,6 x 165 cm (15 x 65” and 42 x 65”) Pencil, charcoal, pastel, wax crayon, enamel paint, wash; aerial photograph with topographic elevations and fabric sample. Photo: André Grossmann, ©Christo 2010. Ref. 044 (All images courtesy of the artist)