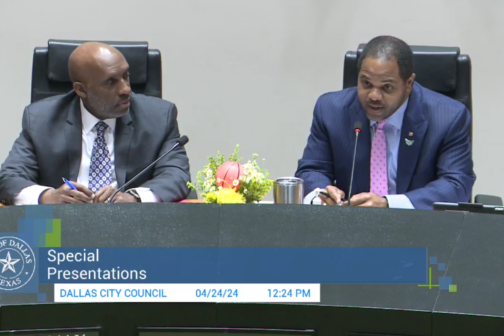

If you were, say, a Super Bowl visitor, wandering into the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and encountering the work of artist Ed Ruscha for the first time, you may think the artist was road-obsessed. That’s how naturally the thematic thread of the exhibition, Ed Ruscha: Road Tested, flows through the four galleries. The show includes work spanning more than forty years of the artist’s career, beginning, in a sense, before the art, with a road map traced with ink, indicating a young Ruscha’s hitchhiking travels through the American South.

It was Ruscha’s second big trip that now seems more significant, the one he took from his native Oklahoma to Los Angeles, CA, a city that would become synonymous with the work of Ed Ruscha. In the exhibition, Los Angeles becomes a blurred scene from the window of a Ford at 55 miles per hour, a landscape of perpetual motion where Ruscha could continue his road trip in perpetuity.

There is more to Ruscha’s lifetime of work than the blur of the mid-century American landscape, but Road Tested succeeds at positioning the image of the road as an intersection of many of the artist’s ideas. And while the aesthetic punch of these works varies, we begin to see the content of the highway landscape as Ruscha’s equivalent of Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Can: mundane, seemingly trivial data lifted from the experience of commercialized contemporary life and glorified, in a qualified way, on the artist’s canvas.

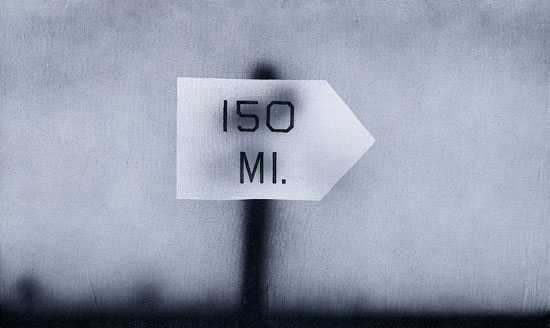

This project takes a variety of forms throughout Ruscha’s career. There are the long thin paintings depicting the Hollywood sign – spelled backwards or forwards – perched atop the Hollywood Hills and bathed in various shades of degraded light. There are Ruscha’s books, anthropological catalogues of architectural styles – from the Sunset Strip to Los Angeles apartment complexes. In Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Ruscha chronicles exactly that: twenty-six gasoline stations found along the road from Oklahoma to Los Angeles, arranged in no particular order and with no narrative significance. The images are clean and uncluttered; there is nothing emotional or sentimental about them. The photos simply stand like specimens collected from an expedition through a Futurist landscape.

Then there are Ruscha’s word paintings, which range from dreamy landscapes to cloudscapes to the pixilated Los Angeles landscape at night –recognizable even to those who have never visited the city – a conglomeration of tiny dots of white paint which create a landscape of flickering light. Onto these, Ruscha overlays, in his trademark font, words that read like stream-of-consciousness associations: “Ice Princess,” “A Blvd. Called Sunset,” or “Life in Rural America.” At the end of the show there is one of Ruscha’s mountain portraits, more Alpine than Californian, yet written on the image are the names of Los Angeles streets. The most immediately available metaphoric meaning of the work points us, again, back to ideas of urban life and travel, struggle and the disposition of place.

Road Tested came together because of two works: Ruscha’s well-known Standard Station paintings. Indeed these two works alone could warrant their own exhibition, surrounded as they are in this show, by the many studies and prints that show both Ruscha’s process of coming upon these clinically executed images, as well as the various variations they have taken through the years.

Both works show a gas station, not unlike many in the photographs in Ruscha’s book, stripped down to its simplest, formal elements. Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas has a flat black sky partly cut by spotlights, while in Standard Station with a Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half the sky is blue and a painted copy of a pop western children story, crumpled and conspicuously placed in the upper right hand of the canvas. In both, two twin red pillars hold up a roof that stretches diagonally from left to right, neatly dividing the canvas into halves, a trail of white continuing the roof’s trajectory to a vanishing point at the very corner of image. A Standard sign juts out to top left of the painting, the bold block letters drawing our attention to the image’s self-conscious simplicity, the pedantry of its recognizable content.

The canvas’s sense of perspective is oh-so-slightly distorted, hinting at the experience of this place as a passing sight, architecture in time. But we are primarily struck by chic style of the work, which still feels fresh and vibrant nearly fifty years after its painting.

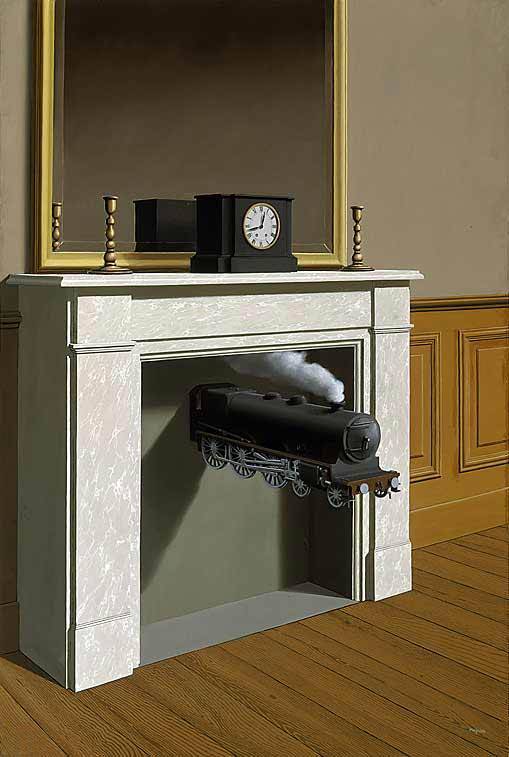

Illogical, otherworldly elements abound in Ruscha’s work, like the torn magazine in the corner of Standard Station, floating in the sky, or perhaps sitting on the image like his letters. There is the odd positioning of the Hollywood letters. Another canvas is dominated by a giant question mark, with a corner of the image painted white in the shape of Oklahoma, looking like a torn out section. Much like the French surrealist Magritte, Ruscha focuses on the everyday or the familiar and then interupts these vignettes with visual non-sequiturs as a way of infusing the image with an unmistakable and unforgettable uniqueness.

Ruscha’s settings are not always scenes – sometimes a greyed-out canvass with a single, intersecting white cross suffices – but they do draw our attention to the particular reality of the canvas and its disconnect from the laws that govern the world outside the work. Text, light, negative space, items from popular culture, the everyday landscape of American lives: all these are mixed and mashed into images composed of such clear, attractive formality that the final work possesses a resounding individuality. We are constantly reminded that Ruscha’s roots are in commercial illustrations, and that, above all, Ruscha is an image maker.

In this way, Ruscha’s work draws strong lines of continuity between surrealism and pop art, and yet his work stands apart from both movements. It is too infused with the spirit of the American West to be neatly categorized. Ruscha did not pick up things from the supermarket or from magazines or from the Hollywood culture that surrounded him. He draws from the ubiquity of the contemporary American experience to create images composed of familiar things that somehow feel recently discovered, unearthed. The character of the artist, who resists being labeled the Los Angeles artist (as he often is) feels rooted in the myths of these landscapes. Sometimes that causes these sun-set scenes, or the parades of ghostly pioneers, to teeter on sentimentality. However, the pragmatism of Ruscha’s formal style, his anthropological sense, keeps his work from getting too nostalgic about this long road trip.

Image at top: Ed Ruscha, Uphill Driver, 1986. Acrylic on canvas; 54 x 120 inches (137.2 x 304.8 cm). Collection Emily Fisher Landau, New York.