One of the consequences of the waning influence of the church at the turn of the last century was that something was bound to take its place. At the same time, modern artists were beginning to shed any recognizable remnants of their particular cultural histories to construct a new future that aimed to be universal and thus poised for wide appeal. Kasemir Malevich turned icon paintings into spare abstractions. Marcus Rothkowitz even shed the offending ethnicity of his name, along with the imagery of his early paintings of the Jewish Lower East side, to become the Rothko that we know today. The essentialism of this reduction was meant to be transcendent and spiritual, creating the piety of modernism.

In the mid twentieth century, as modern art was at its apex, Rothko even worked on his chapel in Houston in collaboration with the architect Philip Johnson and famously withdrew his paintings from a project for the Four Seasons. The purity of abstraction was something to be protected and carefully disseminated. The paintings from the Four Seasons project ended up at the Tate in London, but Rothko could not prevent other examples of his work from being the backdrop of collectors’ dinner parties. Projects such as these reveal that the piety of modernism can be just as easily tarnished as the church, especially when we realize that the rhetoric of contemporary art often combines the riches that it represents with the sublime in a way that is reminiscent of the long history of papal patronage.

This history haunts the newly arrived traveling exhibition Rachel Whiteread’s Drawings at the Nasher Sculpture Center. While the work is not purely abstract, in the tradition of modernist non-objective drawings, it is deeply influenced by a set of high modernist beliefs. But it is important to separate Whiteread’s drawings – many of which are exquisitely beautiful – from the critical and curatorial rhetoric that surrounds them.

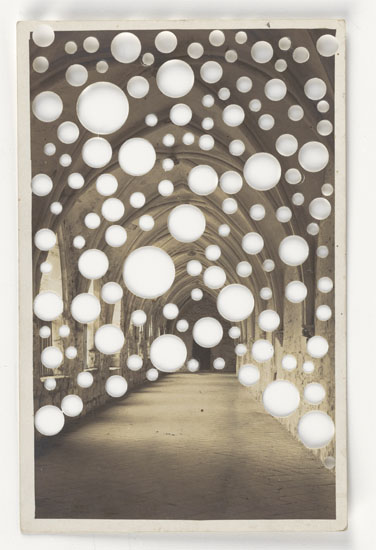

Curated by Allegra Pesenti at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, the exhibition is crowded, with drawings standing shoulder to shoulder in a darkened gallery of the Piano building. This is an ironic decision, since Whiteread’s sculpture is about the space between things, most famously realized and made visible by her sculpture Ghost, 1990, a large plaster cast of a room in a Victorian house.

I suspect that this is the result of a particular approach to curatorial practice, which is connoisseurist and grows out of the high modernist belief of an art object’s autonomy. If each of these objects are like relics with inherent (and not contextual) meaning and value then the space around them becomes secondary.

This belief in autonomy is linked historically to some of the language that Pesenti uses in her catalog essay for the exhibition. Whiteread’s 2000 Holocaust Memorial is described as “a timeless monument that speaks on behalf of multitudes and is accessible to all.” For something to be timeless is to believe that it can exist in any context. Marx’s notion of historical materialism famously critiques this ahistorical view because it has most traditionally been used to prop up the power of monarchies and the church. Directly or indirectly, this idea was greatly influential to many artists in the later part of the twentieth century that were skeptical about art’s participation in power structures. Monuments, similarly, are often used for political purposes, as the controversy surrounding Whiteread’s Vienna monument revealed.

Following many other critics and curators, Pesenti often refers to the haunting trace of loss that Whiteread’s erasures and castings of absences reveal. This takes the particularities of studio practice and generalizes them toward the universal theme of mortality. But the question is if this theme is so clearly present in the work itself.

The exhibition is organized thematically to include various images that Whiteread has explored such as houses and stairs, tables and chairs, beds, and mattresses, as well as public projects such as the holocaust memorial, water tower, and Trafalgar Square plinth.

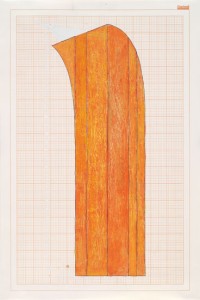

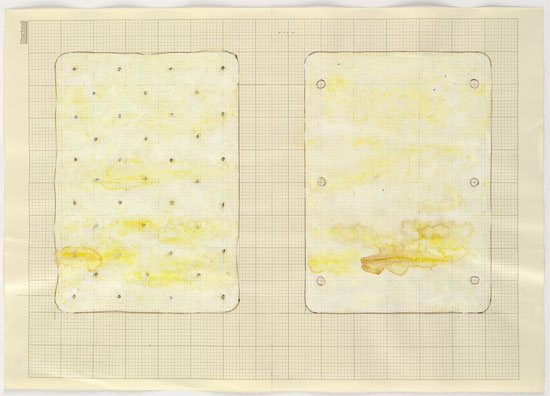

The domestic images play with the implied figure in utilitarian objects such as tables or chairs. The drawings of these images range from the highly abstracted to more explicitly descriptive and even diagrammatic. Flap, 1989 for instance, is made up of two light brown translucent rectangles barely butted up against one another with two dark brown linear forms that rest on the top right corner. Taken out of context, this drawing reads as an abstract composition. But it also relates to a sculpture of the same name that Whiteread made which included two plaster shapes and a dark wood flap from an actual table.

Drawings such as Floor Study, 2000 and Library Drawing, 1996 resemble Agnes Martin or early Brice Marden in their combination of abject materiality and the measured precision of the Cartesian grid. Drawings like Ghost, 1990, use isomorphic projection on grid paper to describe cubic structures of space like Donald Judd or Sol LeWitt. But this is a post-minimal approach, drawing on these abstract histories but eliminating the binary opposition of representation and abstraction. In fact, we now think of the Russian Avant Guarde or the Bauhaus as ideological bastions of abstraction but they were also deeply engaged with design and architecture. Whiteread simply erases these disciplinary boundaries and conflates them into one. This freedom is what disassociates Whiteread’s work from the dogma of modernism. It is her ability to be impure, combining the abstract and the real, the abject with the refined and fine art with design that make this work progressive and refreshing.

But this progress is stifled when the piety of modernism creeps in. When these objects are treated as relics to be housed in the reliquary of the museum it robs them of their openness. Whiteread has never exhibited this many drawings before, choosing to keep most of them private. They were made in tandem with her sculptures and she thinks of them as having equal value. Because of their size and the relative ease of their transport this exhibition is the first real survey of her work. It is a great thing for the Nasher Sculpture Center to host as it allows us to see the broad thematic currents in the work of a thoughtful artist. It would have been greater if the form of the exhibition followed the function of the work.