Paul Levatino is a familiar name to people who have been involved in the Texas music scene over the past couple of decades, mostly from his work with Erykah Badu. With Badu and others, his role was producing, in one form or another, whether that was specific events or videos or just results in general.

But while Levatino was working in a creative industry, he wasn’t always seen as a creative himself, though he had grown up playing in bands and could handle himself behind a camera.

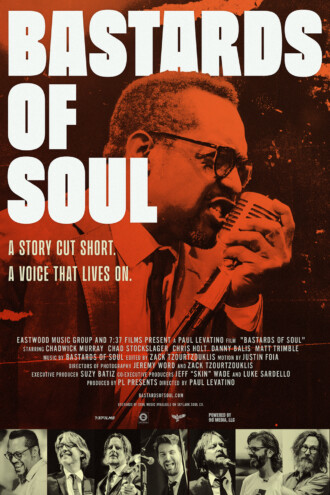

That should change now that Bastards of Soul is making its way into the world. The feature-length documentary, about the titular R&B band, premiered at the Sun Valley Film Festival in Idaho in late February and has its Texas premiere on April 27 at 7 p.m. at the Texas Theatre, as part of the Dallas International Film Festival. The film follows the group as they emerge from COVID to record their second album, Corners, and was originally intended only to be a short promo video. But everything changed when singer Chadwick Murray, a longtime friend of Levatino’s, suddenly fell ill and died.

Corners was supposed to put the band—which includes bassist Danny Balis, drummer Matt Trimble, guitarist Chris Holt, and Chad Stockslager on keys—on the map. Now, Levatino’s film—split between the nuts-and-bolts of making music and an intimate portrait of Murray just before his death—may do that instead.

“Going out to an audience who doesn’t know anything about the band, I think what I’ve realized is the story is really relatable to any creative that’s chasing their dreams,” he says. Which now includes himself: “I’m usually the behind the scenes guy. I’m always the guy who wants to support the creative to get out there. And so for me, it’s been interesting to just accept that I am talking for all of the people that put their heart and soul into this.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I know it took a much different shape along the way, but what was the initial impetus of the project?

I had the opportunity to film them privately at the Kessler Theater. It was part of an EarthX gala event. I thought, well, I could just film them just running through their songs and just get beautiful footage, and no one will be in the audience to block me. And so, I got all this great content. [Jeff “Skin” Wade, co-owner of Bastards’ label] was like, “Oh my God, this is beautiful. Why don’t we go into the studio and just kind of capture a little behind-the-scenes story of them coming out with the album?”

That would be maybe a five-minute piece, making-of-the-album kind of thing. I called my team that was at the Kessler and I just said, “Hey, there’s this opportunity where we can all get back together and go to the studio, but it’s July 4th weekend.” And I was like, “I’ll buy everybody dinner. I’ll take care of everything and throw in some money. Can you guys do this?” And we just went in, and we spent Friday, Saturday, Sunday, and I even think that Monday, and we just filmed everything.

Right afterwards, that’s when Chadwick started falling ill, and it wasn’t ever on my mind to do anything, but on a personal level, I was very close to Chadwick. And the day that I found out of his passing, Max [Hartman, Chadwick’s friend and former bandmate] called me. And he was like, “Buddy, here we are again,” because we’ve had a few friends pass over the years. We’ve known all of each other since high school, even Chadwick, we’ve all known each other. And when he called, I just had this flash of credits, ending credits. And I didn’t know why I saw that in that moment, but I look back on it and I think that was the first sign of, I got to do something.

It’s interesting that you already had the footage, which is some of the most powerful stuff, of Chad talking about his son being born or about to be born, what he wants to do as a father. That hits so hard when you see it.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was capturing this man who was finally realizing his dreams. And everything was coming together for him, and he was wildly chasing his dream to make this happen. He had just gotten married. He was just having his first child. And, privately, we were talking about him quitting his job and going on the road and what that would look like. I was helping him on a management level, but also kind of a collaborator for the band.

When we were filming at the studio, I had this idea. I was just kind of winging it. I was like, “I’m going to capture interviews of what these guys have on their mind at the time.” And the second day I woke up and I thought, oh my God, I need to capture that moment where these guys are getting ready and going to the studio. I want to go into Chadwick’s house and see what’s on his mind before he goes to record that day. And I went to his house. I think Danny was busy the next day. I was able to get Matt; his scene didn’t get in just because of length. I wanted, in my mind, to have The Song Remains the Same [the 1976 Led Zeppelin documentary]. [laughs] I was going to have a two-hour, three-hour documentary, and everybody was like, “No, no, that’s a bad strategy.”

How do you take what was meant to be maybe a five-minute piece and turn it into a feature? Or, I guess, how do you end up with a documentary when you didn’t know you were making a documentary?

Once I started really thinking about it, I was like, “This seems kind of daunting. I don’t know if this is going to work.” And I don’t know if you know this, but I work with Suzy Batiz [the founder of Poo-Pouri]; she’s been a longtime collaborator of mine, and she really encouraged me.

She was like, “You can do this. This is an incredible opportunity to tell the story.” And she gave us the platform to do it. But also like, I was trying to figure out how just to tell the story because it wasn’t like I had planned it and I didn’t have a story in mind. And she was kind of like, “You need to tell the story in a way that you captured it. Tell what happened.” And so I went back and I looked at the footage and it just felt like I had this timeline of incredible concert footage and leading up to the studio session and building towards this terrible inevitable end, but what is the real message? She encouraged me after seeing it that I should really think about what the message is in one sentence.

And I feel like it really tells what the story is to anybody who’s a creative chasing their dreams. And it’s that the trouble is you think you have time. Because I think everybody who is a creative thinks, well, we have time to get to that. But the band was like, “We are out of COVID. We’re going to get in there. We’re going to finish this album. We’re going to get it out.” And Chadwick was super focused on making that happen and becoming that frontman that he never thought he could be.

I mean, he was a bass player. He was never—I mean, I played in a band with him in high school. We jammed in my mother’s guest bedroom. And he never was the guy who was up on the mic. He was just the dude who held down the rhythm section. And then this was his opportunity that he thrusted himself out there. And he really commanded people. I mean, I’ve worked with all kinds of awesome artists like Doyle Bramhall and Erykah Badu and people like that. And he had that. It’s like somehow he captured that where he could grab the audience’s energy and kind of sing over the audience and kind of float. It was just this amazing experience to watch his energy on stage.

It’s still hard for me to believe that he had never done that before. Beyond the voice, because, like you said, a lot of people can sing, but they can’t perform and sing and do that on stage the way he could.

I did this little friends and family screening, getting some feedback from people at Alamo for the release. And afterwards I felt like there was something missing and I just kept on digging. And I found that one little interview of him where he’s talking about the first show: “I was laying on my mother’s floor scared out of my mind. What the hell am I doing? I can’t do this.” And she was like, “Get up off the floor and go do this.” And he was like, “And then I ripped the Band-Aid off and, boom, I did it.”

And I kind of felt it the same way. I never thought I could be a documentary director. I’ve always been a producer. And for me to step out there, I mean, I can only imagine what it was like for him in front of an audience. But just screening it in front of people, I felt that way. I was terrified to go to Sun Valley, Idaho, with all of these filmmakers and all these elite people and screen it in front of people. Nobody knew the band, nobody knew who I was. And it was packed. The theater was packed with 300 people, and I think they all just love the music. It all comes back to that music.

This is your first feature-length film. What was the first thing you shot when you started moving into this world? How did you start doing it?

I had produced some music videos and little mini docs and things like that and stuff Erykah Badu was doing where I would help with the production side of it. But I had never really thought that I could be a director. And sorry to bring the story back to Suzy again, but she’s been a big pivotal role in me chasing my creativeness. And I guess what she calls my genius. Mother’s Day, 2017, I think. She called me and said, “Do you want to shoot a documentary in Honduras?” And I was like, “What are you talking about?” And she was like, “I know this lady. She’s trying to do this alternative treatment. Would you go down there?” And I said, “Sure.”

So I worked on a budget and I put it all together and I got a director and videographer, and then I called her and I said, “Here it is.” And she goes, “Well, I want you to direct it.” And I was like, “Well, I’m not a director.” And she was like, “Well, now you are.” So I think it was really that moment where that was like, “Wow,” I didn’t think I could do it. I went down there scared out of my mind. But I came back and we ended up putting together a really interesting little piece. It’s not public, but when I look back on that work, I’m like, “I can do this.”

Have you ever talked to her about why she just decided you could do this? Why she pushed you in this direction?

I just think she saw my creative side, that I’m not just 50 percent business—I’m 50 percent creative, too. And I think she saw some of my photography. And I had picked up the camera a few times when we were on the road, and I had filmed her behind the scenes. And she really liked my style and was like, “Dude, you can do this.” Yeah, it does take somebody sometimes believing in you and you realizing, if it feels good and you feel really good doing it, that seems to be the marker of you finding your genius and what you do.

You touched on it for a second before, but when did you first meet Chadwick?

We were in separate junior highs, but we had friends who knew each other that played in bands, and we jammed together at a friend’s house. And then he’d kind of come up to me at one point and told me he had heard I was a drummer, I think, and I was like, “Oh yeah, and you’re a bass player.” And you talking about this, I literally remember his mom dropping him off at my house, the bass rig in the back of her car. He had this huge Peavey bass rig. It was a massive bass rig, and…

That’s definitely as early as you can go. Any story that begins with, “I remember his mom dropping him off …”

Yeah, exactly. His mom is awesome. She’s really awesome. And I mean, that was the other thing that making this film I had to really consider. These are people’s lives and we’re talking about all of these people and how they were affected. “Are you OK being in this? And are you OK with this story?”

What was it like the first time you showed a version of this to the band?

A little terrifying. I was just like, “Oh my God.” I was worried that they were going to be kind of like—I was just terrified. “What is this and where am I?” Or, “Why did you pick this shot of me? I look …” Whatever. I think a couple of the guys got back to me pretty quickly. I had asked them for their opinion, give me some feedback, and I took it. And I even met with some of them. I went to lunch with Chad, and I sat and listened to his feedback for two hours and was super open to it and made some adjustments. That helps me. But I can’t take all of the direction from everybody. So that was the hardest part, is to filter that and figure out what’s best for me as a director and what my story is.

But Danny, he didn’t even want to watch it until we did the little screening for the friends and family. And then he saw it and he came up and gave me a hug. And so I really appreciated that. He wanted to wait, which I respect.

For sure.

I mean, I gave Hannah [Murray, Chadwick’s wife] the film the entire time. All the way through I was giving her access, because it was very healing for her and the family to be able to hear and watch. And I’m sure it was terrible, too. It was very emotional.

I mean, it always will be, I imagine, but it’s just such a rare opportunity for their son to have a sort of living, breathing version of his dad that he can see.

And most people don’t get that. And that’s why I dedicated the film to Lennox.

Author