From December 2022

Cinching my tie, I cleared my mind and stepped into the main reception area of the Alcoholism Treatment and Recovery Center, 3949 Maple Avenue. The room was a block of smoke. I gagged and wanted to run but couldn’t because I needed a job.

Located in what was the old Parkland Hospital nursing school quarters at Maple and Oak Lawn, the once-grand room in August 1981 was furnished with fallen couches and chairs that might have come from front yards on bulk trash day. Men who seemed to be ghosts of who they once were milled around, smoking, smoking, smoking, reading day-old papers or beaten copies of LIFE or Look. For this I worked and went to school, indebted myself.

At the semicircular reception desk sat three older guys in worn clothing. Their baggy faces, like those of clowns without makeup in a third-rate circus, each sprouted a lit cigarette. They were answering phones and yelling at men across the room. They seemed too busy to notice me.

“Excuse me,” I said, clearing my already irritated throat. “I have an interview with Earl Osborn?”

One man said, “Who can I tell Mr. Osborn is here?”

Weirdly formal for this setting, no?

“Jim Dolan,” I said. “I’m here to interview for the counseling position?”

The guy grabbed a filthy avocado-green receiver and into it bellowed, “Earl, yer guy is here!” He set the receiver in its cradle and asked if I’d like a cup of coffee. When I declined, he turned back to the other two as if I’d never existed.

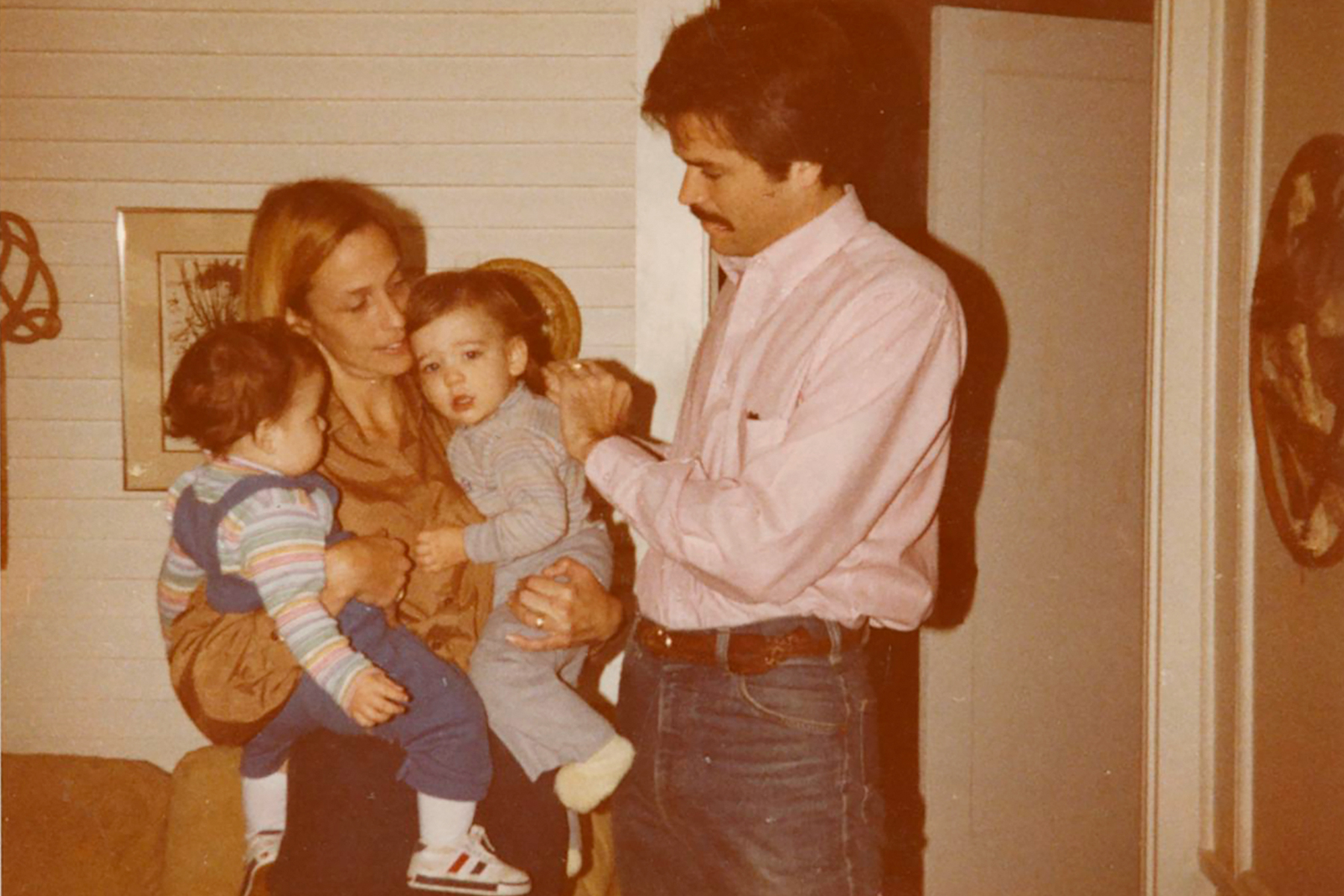

In 1981, I was 30 years old, a green therapist with a patchy employment record of firings, layoffs, and a general sense of being unable to fit in. I had a B.A. in psychology from the University of Dallas and an M.A. in the same from Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, plus postgrad hours from East Texas State University (now Texas A&M University-Commerce). I’d been married for seven years and had a 1-year-old son. My wife was a registered nurse, and her income allowed us to navigate some difficult times.

When I stepped through the door at the Alcoholism Treatment and Recovery Center, I had been fired a few weeks prior from my post as a counselor at the Family Guidance Center of Dallas. General noncompliance, failing to attend administrative meetings, keeping my tie loosened, often late—silly, pointless defiance. Losing my job really stung, though, as I had to cancel the deal on the purchase of our first home, a little Craftsman in Oak Cliff, the neighborhood where I grew up.

I was restless. I had always thought I wanted to be a psychotherapist, but employment was a confounding challenge. Salaries were laughably, insultingly low. My universities had failed to include anything about how to establish a career postgrad. Once you were no longer a warm butt in a classroom, they couldn’t give a damn. And if courses like “Phenomenology of Consciousness” or “Memory and Imagination” didn’t set me up for dealing with habitual criminals, that was my problem.

In 1972, David Ruiz, incarcerated by the Texas Department of Corrections, filed a 15-page handwritten complaint alleging that his constitutional rights had been violated and that his imprisonment was cruel and unusual. His complaint was eventually wrapped up with others into a class-action suit heard in the court of Judge William “Billy” Wayne Justice. Has there ever been a better name for a federal judge?

Judge Justice found for the inmates, kicking off a massive change in the Texas prison system, one of the harshest in the country. By 1980, steps were being taken to build more prisons to lower population density, but it would be several years before that could have any impact. To lower populations, it was proposed that nonviolent inmates be identified immediately after the judge’s orders went into effect, and that those men be paroled to halfway houses contracted with the Texas Department of Corrections. Houses in Houston, Austin, San Antonio, and Dallas sprang up, one of which was the Alcoholism Treatment and Recovery Center at Old Parkland.

I waited at the reception desk for no more than a few minutes before a thin, dapper dude of about 60 emerged from a hidey-hole at the end of a hallway leading away from the common area. Clad in ancient pinstripe slacks, mod boots from that era, and a where-did-that-come-from double-breasted blazer, he looked like a salesman at a tote-the-note car lot. A thick head of silver hair was swept to one side. Glasses with oversize frames swung from a chain around his neck. Of course, he was smoking, but it was a long, elegant Virginia Slim that he held delicately between thumb and forefinger. Earl Osborn sucked on his cigarette as though it was a means of life support.

We went to his office, which was furnished like the reception area, in castoffs. Everything about the place—the building, the people, the clothes—all seemed to have been recycled. Earl fidgeted at his desk, every now and then swigging from a mug with the slogan “Easy Does It” on the side. A red glass ashtray the size of a dinner plate held a mound of Virginia Slims butts.

I noticed my knee was bouncing, but I couldn’t make it stop.

“So, when can you start?” Earl asked.

What did he say? What about the interview? Bullshit questions, bullshit answers, fake smiles, forced laughter, the whole rigmarole.

“I said, when can you start?” he asked again.

“Don’t you want to ask me about my background and experience and stuff like that?”

“I don’t have time,” he said. “I’ve got 75 people checking in here tomorrow, and we need staff. When can you start?”

I had no idea what I’d be doing beyond some vague notion of “counseling.” All I knew was that there was a job, and I needed a job. I’d learn how to treat alcoholics on the job.

Although I drank as much beer as the next guy, I didn’t really know much about alcoholism, except that my Uncle Paul was an alcoholic. He got drunk at age 15 and stayed that way until he died of heart failure, somewhere around 60. When I was a kid, I loved Uncle Paul. He never held a job that I knew of, but he planned to become a millionaire once he discovered a lode of uranium in those Cold War years.

He became my father’s responsibility early on. My dad was an itinerant jack-of-all-trades criminal (see “My Father, the Hitman,” D Magazine, October 2021). They would pull into a town and check Paul into a fleabag motel while my dad did his thing. Paul would pull a bender and raise a ruckus at the motel. The first night in high school that I came home with beer on my breath, my mother asked me if I wanted to “turn out like Uncle Paul.”

I saw how similar psychotherapy was to one of my dad’s cons.

That was all I knew about alcoholism.

Sitting in Earl Osborn’s office, in front of his castoff desk, in a castoff chair, in a castoff building, I was offered a job that only someone who saw himself as a castoff would take. I’d always anticipated a glamorous career, getting paid by interesting neurotics to help with their problems. But I had no idea how to get there. I only knew I wanted to show my wife I could provide.

In my darkest moments, when I fell prey to the notion that I would never amount to anything, I had a vision. In the vision, I saw how similar psychotherapy was to one of my dad’s cons. You gain a person’s confidence, imply that good will come out of the interaction, and accept their money for the trouble. It seemed not too different from fortunetelling.

I calculated the risk in Earl’s question. Is there something I’m missing? Is this some kind of fly-by-night operation funded with money on the come? Will I commit only to find myself without a job in a few weeks, having passed up other more solid opportunities? I didn’t want to seem too eager.

I countered: “Asking me when I can start, that means if I show up tomorrow, ready to do whatever, I’ll have a full-time job, with a guaranteed salary, no bullshit?”

“Jim, we need people of your caliber as soon as we can get them. Would $20,000 be enough to get you to sign on?”

I think he just offered me a $20,000 salary! A $7,000 raise! It was the lower edge of a real salary and put me almost on par with my wife, the nurse.

“I’ll start tomorrow,” I said. “What time?”

Earl broke into a big grin, the kind car salesmen flash when the ink has dried. He extended his nicotine-stained hand and said, “Welcome aboard, Jim. Glad to have you. And I hope 8:30 isn’t too early.”

“See you then,” I said, eager to blast back home and brag to my wife that I’d gotten a job—a good job—and we could proceed with the house.

“One more thing,” Earl said. “How do you feel about inmates—or, rather, people who’ve been in prison? Because it looks like we’re going to have a few.”

Who was I to have a problem with a few inmates when there was one in my own family at that very moment? By then, my dad was doing his time at the federal facility in El Reno, Oklahoma.

When I told my wife, Karen, she said, “You went for a job interview, and the guy didn’t even interview you? He just offered you a job and 20 grand a year? Are you sure?” Understandably, she was having trouble believing my sudden reversal in fortune.

“It’s for real,” I said. “Call the Realtor.”

I was dubious, too, but I kept that to myself.

The next morning, I pulled into the parking lot to find several big buses marked TDC. A trickle of adrenaline started when I realized they were buses from prisons, and they had unloaded the inmates Earl had mentioned we might have a few of. My gut tightened.

I found my way to Earl’s office. “What’s going on?” I asked. “You said some inmates. This looks like a whole lot more than some.”

“About 75,” Earl said offhandedly. “They’re all down in the cafeteria now, waiting for their counselor: you.”

I went down a ramp leading to the swinging doors of the cafeteria, alone, like a gladiator into the Colosseum. The men were in an uproar. Every last one of them had a lit cigarette, a pall of smoke hanging under the high ceiling. Some guys were passing a porn mag around. Others were gathered in small groups filled with constant movement.

The previous morning, guards had gone into select cells, rousted the guys out of their bunks, and told them to gather their shit. They were going to Dallas. They were not told what for, so they were suspicious. Once they realized it was a halfway house, euphoria hit, and now the celebrations had begun.

I had no preparation for this. Other than two years working at the Terrell State Hospital Adolescent Unit, I had zero experience with institutionalized people who’d had their self-determination taken from them. Now a measure of that had been returned to these guys without warning, and they were going nuts.

The room reeked of body odor. There were bad haircuts, rough beards, clothes torn from bags of used garments at the prison, roll-your-own smokes, tattoos, jagged teeth, scars. The men were terrifying. Just a few weeks before, I had worked in a suburban office of the Family Guidance Center, moderating marital feuds, dragging words out of sullen teenagers, and wondering if this was really what I wanted to do with my life. It was as if I’d trained for ground combat by camping with the Boy Scouts for six months.

“Guys!” I said. “GUYS!”

Nothing. Bedlam continued. The magazine with the giant breasts on the cover continued to make rounds. The group broke down to about one-half Black, one-quarter Hispanic, and one-quarter Anglo. But they were all ill-behaved, emotionally stunted, hostile, violent boys in the bodies of men.

“HEY, GUYS! MY NAME IS JIM DOLAN. I WILL BE YOUR COUNSELOR WHILE YOU ARE HERE AT ATRC!”

That quieted things down a bit. Then a voice came from the back. “Hey, man, if you the counselor, then just break it on down. Start counseling. And we’ll tell you when to stop.” Guffaws, belly laughs.

I walked into the groups knotted at the cafeteria tables around the room, reaching out to shake hands and introduce myself. A few played along and shook hands, but most just looked blankly, while others seemed to be measuring what kind of physical threat I posed. I would not have been much of a match. I was razor thin in those days from habitual running, a stress control ritual I’d had since college. Despite my dad’s boxing lessons when I was little, I couldn’t throw a punch.

I saw one bald guy in a pair of shades and noticed a tattoo on his shiny dome. I worked my way around behind him to get a better look. A tattoo on top of your head? That must have hurt! The image was of Coyote—how can I say this?—in congress with a bent-over Road Runner, with a speech balloon saying, “Now I gotcha, motherfucker!”

The owner whirled around, put his hand to the top of his head, and said “Hey, man, you like my tat?” I thought the guy was going to attack, but he was just proud of his skin art.

“Yeah, man, I think that’s really great,” I said and walked out of the room, leaving them to the house staff. I would have a talk with Earl later.

Most of the guys, I’d come to learn, had chosen their parents poorly. Their families were uneducated, marginalized people, riddled with addiction, violence, and the pathologies of poverty. School-wise, they had completed less than the eighth grade. Most had turned to crime to survive: petty thievery, burglary, auto theft, drug dealing (and consumption). They were people violently at odds with society. No one cared about them, so why should they care about the people they robbed on the street for the cash in their pockets? And once they became criminals, there was almost no way to back out. They were on the wheel of lifelong recidivism.

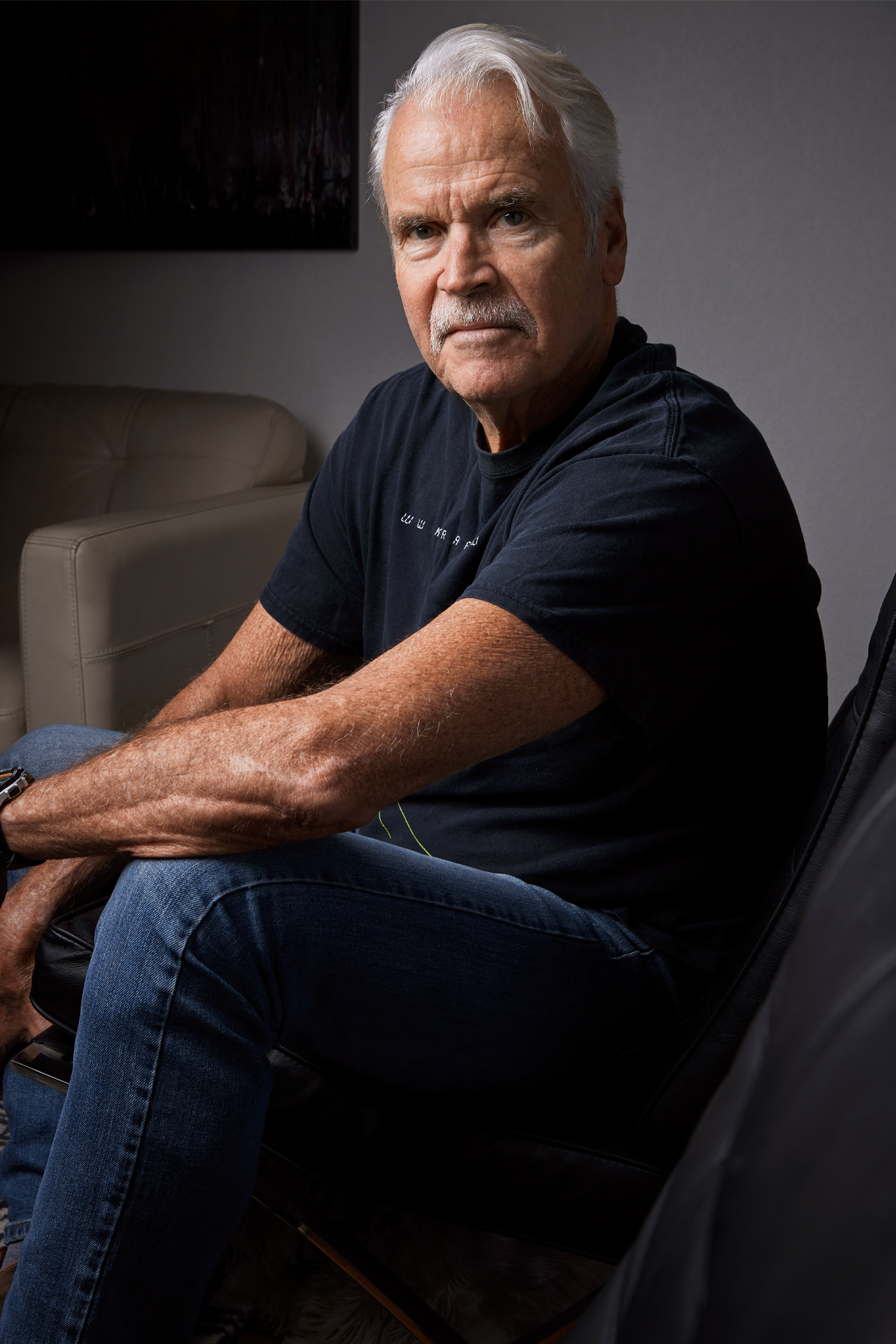

Looking back from 40 years out, I see sons. We were all sons in that old building, some raised by jackals, some by the abandoned women who bore them, and some by ghosts. My father in prison was a son. I was a son. We were all sons looking for or running from our fathers. I made an oath to my own son, Ryan, that his life would be different. And it was.

We were all sons in that old building, some raised by jackals, and some by ghosts.

But some of those sons were just bad guys. I was blind to that. I eventually got comfortable enough to hire a few of the skilled men to help me with renovations on my house. What a stupid mistake that was, letting them know where I lived. My home was burglarized repeatedly for a number of months afterward. I knew who did it but could not prove it, and I had only my own ludicrous naivete to blame.

Where he was solicitous before, Earl, a few days after my hire, was distant. We sat in his office with Styrofoam cups of bitter instant coffee.

“You indicated you were comfortable with inmates during our interview,” he said, tapping a 2-inch ash off the end of his Virginia Slim. He was hiding something behind his eyes.

Yeah, Earl, but you were not honest—or was he? Maybe I was so blinded by my need for a job that I didn’t see all the red flags? What did it matter, anyway? My wife had already called the real estate agent. I had to hold onto this job, or whatever it was.

Earl continued: “We’ve broken down that big group you met with the other day. They’re in the basement group room now. Just talk to them about jobs, house rules, family matters, that kind of thing. You know the drill.”

My first big trial was coming up, but I didn’t know the drill at all. I walked into the basement room with my group of 20, and they reacted like a pack of predators playing with their food, taunting, insulting, degrading me. I stumbled through the meeting, presenting topics but getting nowhere. I was not in charge. And I had not the faintest notion of how to change that.

I had never dealt with stress like this before. I got a sinus infection. I couldn’t sleep. My eyes watered constantly from secondhand cigarette smoke. I was in a near-constant state of panic, on the verge of tears. I lived with shame that my life had come to this, after all the years of struggle in school.

A trans woman named Miss Kandi Luv was a member of my group. All the guys in the group knew her, or knew of her, as she’d been famous down at the prison. Kandi was well over 6 feet in the platform sandals she wore along with extra, extra brief cutoff jean shorts and red bandanas tied over her nonexistent breasts. Kandi flirted with me mercilessly, and I had no idea how to deal with it.

“Honey, you so pretty,” she’d say. “You sure you don’t want to play with Miss Kandi Luv?”

“He’s tired out, Kandi,” another member of the group would say. “He don’t wanna play with you cuz he already played with his missus this morning. Ain’t that right, Counselor? I bet she’s sweet, too.”

Should I respond or just ignore it? I was out of my depth, and they knew it, sensing my insecurity and weakness. There was only one cure for this madness I’d stumbled into.

The Texas Department of Corrections paid the halfway house per man and per diem. Don Cawley, the clinical director (who died in 2018), was betting he could fully staff ATRC with professionals and lay workers on that model. But he failed to take into account who was on the other side of the arrangement. The Texas Department of Corrections began cutting the per diem soon after ATRC opened, and as the budget shrank, so did the staff. Graduate-level counselors, bachelor’s-level social workers, administrative staff, and house staff all had to be cut as the money dried up. Earl Osborn became frequently absent, and when he was around, he was evasive. He was a recovering alcoholic, and I began to suspect that he’d relapsed.

One night a few months in, I was eating alone in the cafeteria before the weekly shit show with my group. I could barely keep food down. My thoughts were a jumble of Miss Kandi Luv; Daryl, a big red-headed, red-bearded redneck with a crown of thorns tattoo on his shaved skull; and Lance, a little punk with a squeaky voice who was the main wisecracker. Into my misery stepped a guy I recognized from the group but to whom I’d never spoken.

“Mind if I have a seat?” he drawled.

He was slight, with a black beard and lank, black hair. He was wearing a new Western shirt and a new pair of boots. I guessed he had someone out there who cared about him. I gestured to a chair.

“Andrew,” he said, extending a firm hand. We shook. “Mind if I share some advice on how to deal with these fools?”

I knew he was right. I was the star of my own prison movie.

My gut tightened. “No, not at all,” I said, trying to appear calm.

And then he lit into it. His eyes grew hard and glittery. “Man, you gotta put a stop to this shit. Kandi and Daryl and Lance ain’t the whole group. There are some of us here who appreciate what we got, and we don’t like these fools ruining it for us. You got to show your manhood.”

“By that you mean … ?”

“Don’t pretend like you don’t know what I’m talking about, man. In the joint, sumbitches test the new blood, and the new blood’s gotta stand up or kneel down. Which you want? ’Cause right now, you’re kneeling down, and it ain’t gone git no better.”

I knew what he meant, but I didn’t want to know, because it scared the hell out of me. I knew he was right. I was the star of my own prison movie. I thought about my dad up in El Reno and wondered if he’d ever had to show his manhood. I thanked Andrew, rose, and strode out of the cafeteria, energized.

I surveyed the room. The bad actors were already in full effect, insulting me, making kissing sounds. Adrenaline sent tingles through my gut. I felt like I was watching myself in that movie. Then the actor playing me said with a loud, commanding voice: “You guys shut the fuck up! NOW!” The racket stopped, and they all came to attention. I recognized the voice, and it was my own, but it came from a previously unknown place.

The voice continued: “From now on, this bullshit will stop. You will be polite and act like adults in this group. Do I make myself clear?”

There was silence, so the voice went on: “We can settle this right here, right now, or we can do it out in the parking lot, but it will never happen again.”

Miraculously, they all became meek schoolchildren, hanging their heads. Again, the voice: “Daryl, Kandi, Lance. You will meet with me alone when we close this session.” Then the movie faded out of focus.

I held private meetings with each of the troublemakers. They all expressed their gratitude to me for taking control, each blaming the others for being the cause of the mayhem. The plan worked, and yet I had no idea how it worked or why. From that evening onward, I had no more trouble from any of the clients at ATRC.

I was employed at ATRC for about two years, until August 1983. After the unforgettable early experiences, I have little recall of what my daily life was like there, except that I became comfortable with and even empathetic to the men. My main memory is of steady decline. Don Cawley’s noble attempt to help neglected people who were trapped in an endless cycle of incarceration was gutted by the Department of Corrections. In the last days, my few colleagues and I were little more than turnkeys, signing guys in and signing them out, keeping track of their comings and goings in an oversize spiral notebook.

The staff was almost all gone. The old building was a shell, a ghostly storage facility for unwanted humans. There was little we could do to control the clients’ behavior, which grew worse over time. Drug deals in the parking lot, hookers in client rooms. But still they came on buses marked TDC.

Among those last men who got off the bus in 1983 was a gent whose last name was L’Esperance. I marveled at the irony that a man with such a moniker—“The Hopeful One”—would find himself in such a forlorn outpost. L’Esperance was a short, blocky guy with a pug nose and heavy black whiskers. He looked like a character in a movie from the late ’40s. He combed his hair straight back and had an elaborate hygiene routine involving a close shave, aftershave lotion, deodorant, and any number of other potions and concoctions. He would come downstairs every morning in a thrift-store short-sleeve dress shirt, polyester slacks, and shiny but worn dress shoes. He carried with him the day’s paper, a pen, a spiral notebook, a Styrofoam cup of coffee, and a pair of reading glasses.

I remember all this because I had, without recognizing it, become obsessed with the ostentation of his morning routine. I studied his movements and his wardrobe, and I recorded them in the big Client Log. But my entries were becoming increasingly literary, bombastic, and full of condescension for L’Esperance. He would set up in the day room and lay out his accoutrements and then begin poring over the want ads. He would theatrically circle things that looked engaging and make notes of them in his notebook. He could easily consume a morning in this manner.

I was making an entry in the Log about The Hopeful One on a Friday in 1983, cracking wise at his expense, to the amusement of exactly no one but myself, and even that wasn’t going too well. Focusing on his pretenses had served to distract me from my own despair. But then, even as I scribbled, a crack opened in my head, and I had a moment of self-awareness as I sat and pontificated on hapless L’Esperance. I saw the stasis in my own life, and my own pretenses, and the way I kept circling around the fact that I was going nowhere and risking nothing.

I felt intense shame when I saw what I’d been doing. I could not go on another day, another minute, with the charade of my life.

At 3:30 that afternoon, I took down the M.C. Escher print showing a chain of lizards climbing out of a page, up a stack of books, and back into another page. I emptied the miscellany in the desk drawers, got my few books, and put the whole shebang in a box. I tore a blank sheet out of the Client Log and left this note on my desk: “Consider this to be notice of my resignation. I will not be back on Monday. All best, Jim Dolan.”

I carried my shit down the hall to the side entrance, kicking the heavy steel door open. The hot blast of August hit, brutal sunlight on the sad squalor of the pitted asphalt parking lot. Somebody had a boombox going, Billy Idol singing. A couple of the guys were sitting in cars with their girlfriends or wives. I had no plan. I was elated and terrified. The future loomed; the past died.

A gust of emotion blew up inside me, and I had to hurry to my car to avoid being seen with tears running down my face.

Postscript: The Old Parkland Hospital buildings and grounds at the intersection of Maple and Oak Lawn were taken over by Crow Holdings in 2006, with an eye to transforming them into the ne plus ultra of commercial real estate. They succeeded, and then some. I have since learned that those wishing to rent space there must first apply and then interview with other tenants, who in turn accept or reject the application. The development, home to some of the most expensive office space in the country, does not lease to law firms.

I visited a colleague who has offices there sometime around 2017. The level of refinement and polish was stunning. It was like the set of a utopian science fiction film. The main reception floor where I first greeted Earl Osborn had been removed entirely, and I was able to look up two stories to a large window in what had once been my office overlooking Maple Avenue. I almost felt like I’d run into a much younger version of myself walking down the hall, so powerful were the memories.

After I left ATRC, I did various handyman jobs for a year or so, occasionally getting a private practice client from colleagues whose offices I would use for the purpose. In 1984, my father was murdered. He left me enough money that I could build my private practice, my occupation of almost 40 years and counting.

This story originally appeared in the December issue of D Magazine with the headline, “My Adventures with Ex-Cons.” Write to [email protected].