“I’m not missing basketball,” he said almost two months later, the day before his annual celebrity baseball game in Frisco, after The Athletic’s Tim Cato asked if he was bored with retirement yet. “I’m not missing working out one bit, to be honest. After such a long time of always having that pressure of staying in shape and keep doing stuff, it’s kind of been nice just to sit and enjoy the kids and enjoy some good food and some drinks. Just enjoying life.”

He’s earned that. But, as he would put it: obviously, basketball will miss him. Obviously, the Mavericks will miss him. Obviously, Dallas will miss him.

He’ll still be around, of course. His Dirk Nowitzki Foundation is headquartered here. He’s raising his three young children here. He may even, at some point, pop into a Mavs game, waving to the crowd during a break in play. But what will it be like, when the 2019–20 season starts, to know with absolute certainty that we will never see Nowitzki on a basketball court again? Never see him catch the ball at the top of the three-point line at the end of a delayed break, trailing the play, rising up with that high-release, high-arcing shot with the form straight from a WikiHow page on shooting a basketball, the ball slipping through the net like vapor, the result never in doubt, then him running [broad wink to the camera] back up the court, sneer-smiling, that low fist pump like an uppercut, something awkward yet graceful about every single part of it. What then?

What follows is an oral history spanning Nowitzki’s entire basketball life. Part of it was assembled 10 years ago, after his first decade in Dallas, and ran in a slightly different form in the December 2009 issue of D Magazine. The rest of the interviews were conducted in May, June, and July of this year.

Part 1

A Phenom Is Discovered

The son of a German national women’s basketball team member (Helga) and a competitive-level handball player (Jörg-Werner), Dirk Nowitzki was perhaps destined for some level of athletic achievement.

His first sport was tennis. Like many Germans, Nowitzki picked up a racket following the Grand Slam successes of Steffi Graf and Boris Becker, and rose to become a nationally ranked player on the junior circuit. Eventually, he grew too tall for the game. By then, young Dirk was more interested in basketball anyway, after seeing the 1992 U.S. men’s Olympic team, aka the “Dream Team.”

But though a few Germans had made it to the NBA—and two, Detlef Schrempf and Uwe Blab, played for the Mavericks in the mid-1980s—the idea of following them to play in the same league as Michael Jordan and his Dream Team teammates was less a fantasy than a delusion. So he was tall. So what?

That began to change when he was 16. At the time, Nowitzki was playing for his local club team, DJK Würzburg. After a game in one of the villages around Würzburg, he met Holger Geschwindner, a former star of the German national basketball team. Geschwindner was struck by a “tall, skinny kid running around on the court,” raw and unpolished, but loaded with potential.

Holger Geschwindner, Nowitzki’s coach and mentor: He did a lot of things right, what a good basketball player is able to do, but he had no technical skills. No shooting. No dribbling. But you could see the guy had a sense for the game. We shared the same locker room, so I said, “Hey, who is teaching you the tools?” And he said, “Nobody.” So I said, “If you want, we can do it.”

Three weeks later, we played a game in Würzburg. He and his parents and sister were there. After the game, Helga came over and said, “Hey, Dirk told us you offered to practice with him. Can we do that?” So we started the next day.

After about three weeks, I told Dirk, “If you want to be the best player in Germany, we can stop practicing right now. If you want to be with the best guys in the world, we have to practice every day. It’s a major decision. But you have to make it.” Next day he called and said let’s try.

Their program was unorthodox in basketball terms, more like a private school education, with Geschwindner encouraging Nowitzki to learn an instrument (he chose saxophone and later switched to guitar) and read literature. This nontraditional methodology helped them overcome what they lacked in traditional resources.

Since Nowitzki was playing for a second-division youth team in Germany, no one was paying much attention to the rapidly growing (and improving) teenager. That changed in 1997, when Charles Barkley, then finishing his career with the Houston Rockets, led a team of NBA players through Europe for a series of exhibition games as part of the Nike Hoop Heroes Tour. In addition to Barkley (whose play with the Dream Team inspired him to wear No. 14), the squad included Chicago Bulls star Scottie Pippen, a poster of whom hung on Nowitzki’s bedroom wall.

Charles Barkley, NBA Hall of Fame forward; NBA on TNT studio analyst: Dirk put up a smooth 50 points. He was too big for Scottie Pippen and, I forget, we had another really good defender—I can’t remember who it was at the time—and he just whooped their ass. I walked up to him after the game and I said, “My man, who are you?” And he was telling me he was like 18, 19 years old, and I said, “Well, whatever money it’ll cost you to go to Auburn, I’ll pay your way for you to go there.”

Auburn never followed up on Barkley’s offer. But Cal offered Dirk a scholarship, as did Kentucky. Any hope of him accepting one of those disappeared when Nowitzki was chosen to play with the World Select Team at the Nike Hoop Summit in San Antonio. Playing against future NBA starters Rashard Lewis and Al Harrington, he scored 33 points and grabbed 14 rebounds.

Geschwindner: He still has the record, as far as I know. We came home after only one game because his club team was in the playoffs. We got in trouble for that. But the first NBA team showed interest. European club teams made him offers.

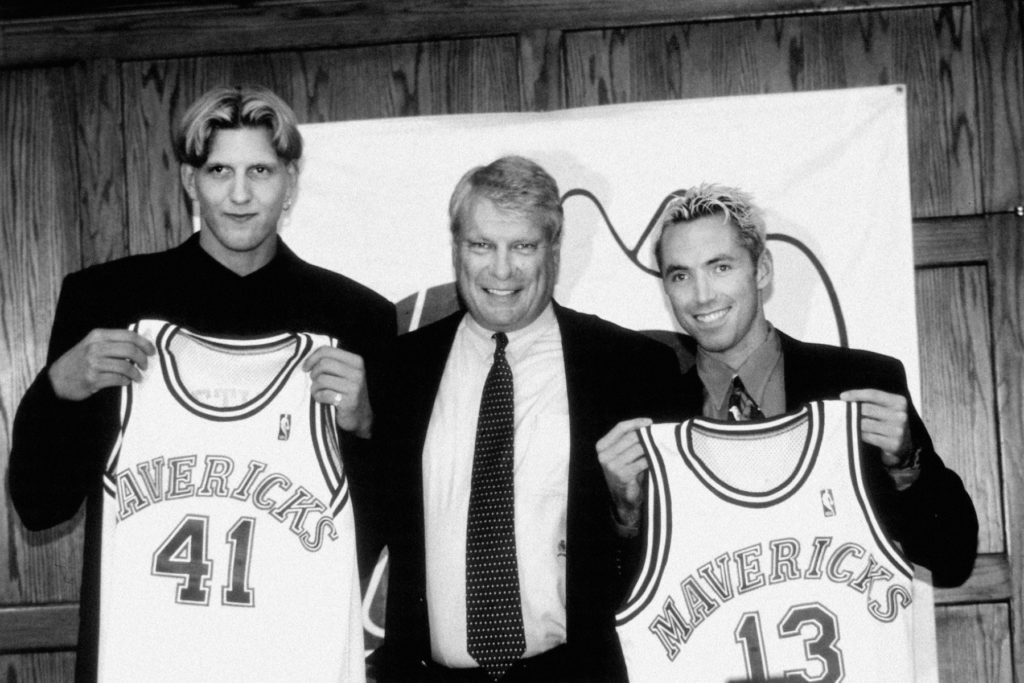

After the Hoop Summit performance, Geschwindner encouraged Nowitzki to submit his name for the 1998 NBA draft. They thought he would probably be selected in the second round. On draft night, he went to the Milwaukee Bucks with the No. 9 overall pick. They immediately traded his rights to Dallas for future overweight journeyman Robert “Tractor” Traylor, a deal that will be on roll calls of worst NBA trades as long as there are such lists.

Fans were skeptical, especially since proven college players were available and, just the year before, the Mavs had picked Chris Anstey, a disappointing 7-footer from Australia. Meanwhile, the Mavericks’ brain trust—coach Don Nelson and his son Donnie—weren’t even sure if Nowitzki would come to Dallas.

Donnie Nelson, Mavericks general manager and president of basketball operations: It would certainly have been a lot easier for him to stay close to home—you know, play there for a couple of years and then decide to come over later. I mean, that would probably have been the kind of logical development steps. But he had a passion to play in the NBA; he wanted to compete against the best. After we drafted him, we kind of set off on a little recruiting trip.

Geschwindner: Two hours after the draft, the phone rang, and Don Nelson said, “We are coming to Germany.” He came and stayed at my house. I lived in an old castle in those days. They stayed for three days and convinced us, at minimum, we have to come to Dallas. That was the year when there was a lockout, so we only had three days. That was pretty much the situation when he had to make the decision: sitting on Don Nelson’s pool all night long and saying, “To do or not?”

Dirk Nowitzki: Nellie had a party, a barbecue at his house. They just said, “Hey, there’s really no pressure. Why don’t you just come and get better? We’re not going to be really a playoff team, and you can develop your first couple of years.” After talking to the players and talking to Nellie, I said, “OK, I’ll try it.”

But he didn’t come over right away. A labor dispute led NBA owners to declare a lockout of their players while they hashed out a new agreement. The season eventually started, but it was a shortened 50-game schedule instead of the usual 82.

Marc Stein, Mavericks/NBA beat writer, Dallas Morning News, 1997–2002; New York Times NBA writer: The NBA lockout was great for me because I was actually in England on one of my soccer trips, and, if you remember, Dirk decided to keep playing for his German team during the lockout. I actually went to Germany and spent a week down there, watched him play in two games, and really, except for Donnie Nelson, I think I was just about the only person in town who had actually seen him play, besides that game he played in San Antonio in that Hoop Summit.

Nowitzki: I didn’t sign my contract yet, so I was able to go back and play with my home team and stay in shape and live at home for a couple more months. And one day—in January, I remember the day—like CNN or whatever said, “Season saved.” And I was like, “Shit. It’s actually going to happen.” I was a little scared, because it was a big step.

The Typhoon

During the 1998 draft, the Mavericks made another move that, at the time, was unpopular, trading new draftee Pat Garrity to the Phoenix Suns for third-string point guard Steve Nash. For the Mavs, the deals would eventually pay off handsomely on the court. But Nash’s arrival paid immediate dividends off the court, providing their new European project with a built-in best friend.

Nelson: I don’t think any of us had any idea that we’d be talking about picking up two MVPs in the same transaction—two league MVPs, I mean. I don’t think that’s ever been done before.

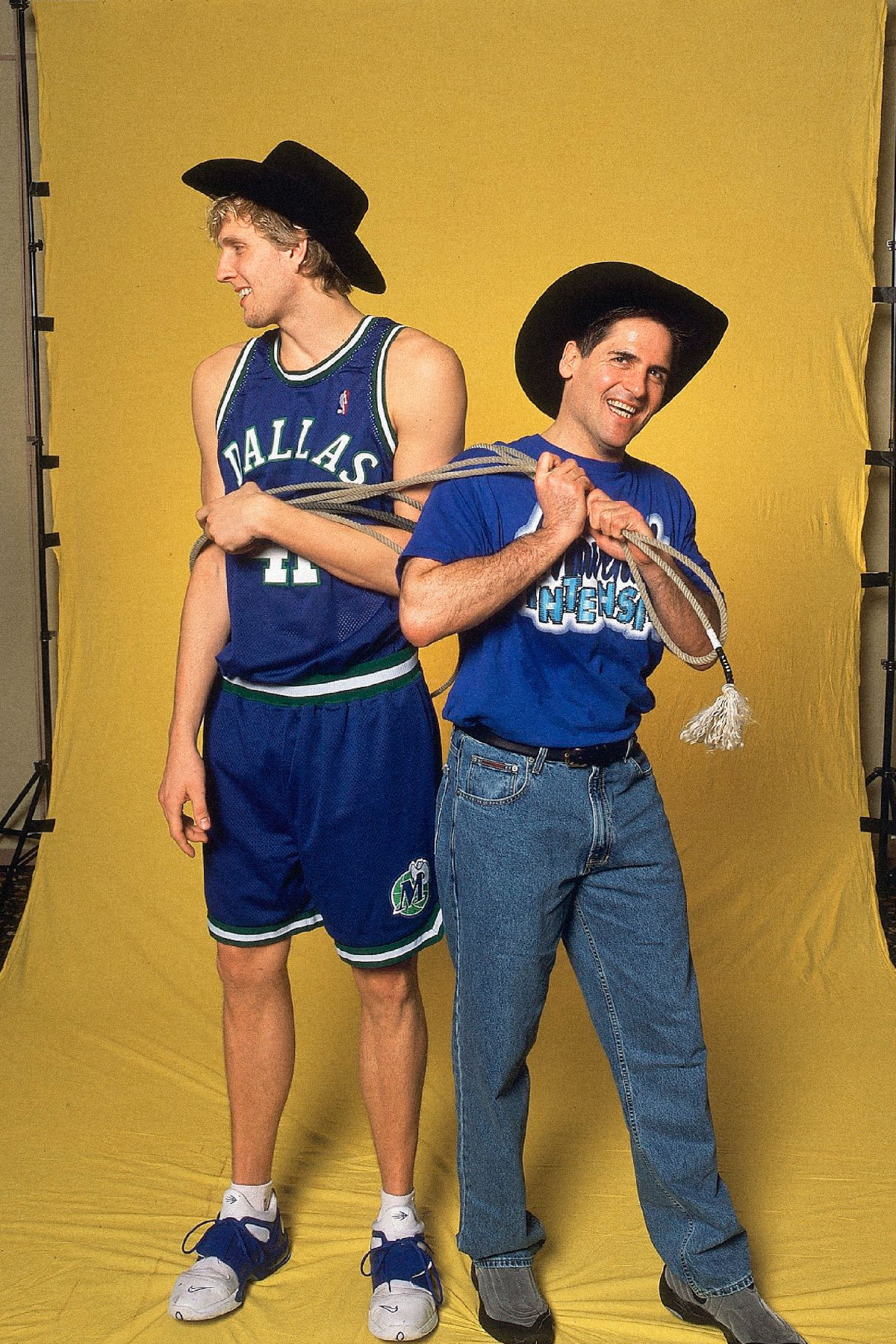

Nowitzki: We had the press conference together when I first got here. He had the bleached blond hair, but it was already grown out for a month or so, so it was, like, dark here, bleached there. It was a terrible look. I had the bowl cut with the earring in. I still see that picture. It makes me laugh.

Steve Nash, Mavericks point guard, 1998–2004: We were both new to town, new to the club. We didn’t know anybody in town. I felt like I could help him sort of assimilate to new surroundings.

Stein: Steve, you know, ran his life in the early days. They lived in the same apartment complex [near where West Village is now]; Nash took him everywhere. I mean he really kind of was his watchdog.

Nowitzki: On the road, when I was sitting in the hotel room, getting homesick, Steve’s like, “Come on, let’s go. Let’s go eat. Let’s go to the movie. Let’s go see some of my friends. Let’s go out.” Which was great for me because I didn’t want to sit in the hotel room every road trip or at home all the time. I was, like, four doors down. I’d go over there all the time. I had his garage code.

For many, Nash and Nowitzki’s relationship was summed up by a series of beer-soaked photos—taken at Woody’s Tavern in Fort Worth, after they were knocked out of the playoffs in 2003—that hit the internet.

Nash: It was a regular night. The only thing that made it different is that someone had a camera. Will they ever go away? I hope not. Classic.

Nowitzki: It was different back then. The Mavericks, in the ’90s, had a tough decade. We’d go somewhere all the time, and people were like, “Oh, you’re tall,” but they had no idea who I was. And Steve, obviously being so small, he could just blend in.

Gavin Mulloy, marketing director, Legacy Hall; longtime Mavericks fan: I once kicked Nash’s shin accidentally at The Loon when he and Dirk were drinking. Like repeatedly kicked. Thought it was a bar stool.

Despite Nash’s presence on the team and his life, Nowitzki’s first season essentially was a complete wash. He was stuck on a terrible team that didn’t appear to be going anywhere, in a country he had been to a handful of times, and he didn’t fully understand his teammates, the NBA lifestyle, or his coach’s erratic substitution pattern.

To make it worse, the Dallas Morning News ran a weekly graphic comparing Nowitzki’s progress with what rookie sensation Paul Pierce, drafted immediately after Nowitzki, was doing in Boston.

Geschwindner: When he was 17, at the very beginning, I gave him a book: Joseph Conrad’s Typhoon. I said, “Hey, Captain MacWhirr, there’s a typhoon coming on!” [laughs]

Jason Kidd, Mavericks point guard, 1994–96, 2008–2012: It’s hard for a rookie, period. But then to come from Germany or Europe, it just makes it a little bit harder, because everything is new.

Lisa Tyner, Mavericks senior accountant and payroll manager: He never really lived away from home. He’d never had his own checking account or anything like that. He was trying to write things in English instead of German, so he would bring things in to make sure that he wrote the right words for the numbers. We just developed a friendship. A little while later, his mom came over. There was quite a large stack of mail in his apartment that contained some checks and things like that. She said, “I think you need some help.” And I said, “All right, we’ll help him.”

Nelson: It’s a jolt to the system. And it’s not just the difference of food, and the difference of language, and all the obvious things. When you’re thrown into an industry that you’ve got veterans, guys with families to feed, that are looking at you like a piece of meat, it can test the best athletes and the best competitors.

Stein: I remember Nellie gave me a great story—didn’t do Dirk any favors—but Nellie said, “Yep, Dirk’s gonna be Rookie of the Year.” He didn’t exactly lower expectations on the way in.

Nash: It didn’t do him any favors. But, in some ways, maybe it made him tougher; put him in the fire right away.

Cedric Ceballos, Mavericks forward, 1997–2000: His rookie year was shaky because Coach Nelson put a target on his back by saying he would be Rookie of the Year. Every team and player was gunning for him. I thought it would be better to let him sneak up on the league. Dirk also had two extra workouts a day, whether we had a game or not. Which later would pay off. So during games he was so tired he would get two fouls quickly just so he could come to the bench and rest.

Stein: It was just a bad year all around. He didn’t really talk about it at the time, but he definitely said years later that he gave real thought to going back to Europe after the first year.

“So once I was here, I thought, Now you’ve made the decision. You have to at least fight through the first contract and see how it goes. I figured, if it doesn’t work out, I can always—after three years—go back and play in Europe.”

Jeff “Skin” Wade, Mavericks broadcaster, 2009–present: I just found out recently that even after his first year, his dad thought it was possible that he might still come home and take over their family painting business.

Nowitzki: I think once I made the big step I thought, OK, I’ll finish at least the first contract. The big decision was to come. Because I had other offers. I could have gone to Milano or I could have gone to FC Barcelona in Europe and obviously been closer to my family. So once I was here, I thought, Now you’ve made the decision. You have to at least fight through the first contract and see how it goes. I figured, if it doesn’t work out, I can always—after three years—go back and play in Europe.

Nash: I knew he was too determined, too hard a worker, too connected to the challenge of becoming an NBA player that he wouldn’t go home. But it was really hard for him. He was 19. He lived with his parents. To come all the way over to a professional league, a different culture, physically he wasn’t mature yet, or mentally—that’s difficult.

Nowitzki: My first year, I lived in that place over there with Steve, just on rent. And I knew I was just going to be here for a couple of months, so I didn’t want to buy a car right then. So I rented a car for my first full season here. I forget what. It was maybe a Cutlass or a Hyundai. The guys would always kill me: “Get a car!” Gary Trent was always murdering me. I don’t think it even had air conditioning.

Stein: He used to just take unbelievable amounts of abuse for his clothes. You know [Michael] Finley was kind of Jordan-esque, as far as he wore a suit and tie every single game, would never do an interview until he had his suit and tie on, and Dirk was wearing, like, flannel shirts and Top-Siders, jeans. In an NBA locker room, that’s gonna get you slaughtered.

Nowitzki: They cracked on me for a lot of things. First of all, I had trouble understanding the language a lot. I looked at them and had to say, “What?” a thousand times. They still make fun of me, because all I would say to them was, “Ya, sure, sure.” Cedric used to always kill me for my accent. He said I sounded like Arnold Schwarzenegger when I spoke English.

Ceballos: Off the court, he was always big-eyed about everything. He smiled a lot when learning about American things and ways. Loved to watch something on TV or a movie and repeat it around us like he was cool. Not too good of a dancer, but that did not stop him from trying—daily.

Though his rookie year was rife with on- and off-court adjustments, Nowitzki found a glimmer of hope near the end—when all hope for the Mavs’ season had long since been extinguished.

Nowitzki: The most important thing, I think, at the end of my first year, Nellie said, “Hey, we’re out of the playoffs now. We’re out of the hunt. Now, we’re going to throw you back in the starting lineup. Why don’t you just try to have some fun out there?” I’ll always remember that one game in Phoenix. I think I had, like, 28 points. That was huge for my confidence, for when I left after the first year.

Stein: He went to summer league and that was big. The first year—and he has said this, too—he didn’t have a summer league, and he didn’t have a training camp, and that hurt him. That would have been some big adjusting-to-America time that he never got. So he went to summer league, was the best guy on that team, and then pretty much right away started making improvements.

Nowitzki: We all know that this league is all about confidence, and once you have it, you’re a different player.

The Big Three

It would never be so bad again for Nowitzki. The next season, he started to become the player the Mavericks thought they had drafted, whose unique skill set made him a match-up nightmare. He averaged more than 17 points and six rebounds and finished second in the voting for the NBA’s Most Improved Player award.

It got better. Toward the end of the 1999–2000 season, billionaire (and Mavs season-ticket holder) Mark Cuban bought the team from Ross Perot Jr. Combined with Cuban’s financial support and the strides made by Nowitzki, Nash, and shooting guard Michael Finley (a trio that came to be known as the “Big Three”), the Mavs finished 53-29 and made the playoffs for the first time since 1990. There, the upstart squad stunned the Utah Jazz in five games, aided by Nowitzki’s 33 points in games 3 and 4.

Mark Cuban, Mavericks owner, 2000–present: It was amazing to come out of our hotel the day of the final game of the series and see hundreds of Mavs fans, in Utah, cheering our team on. Then, after we won, to have those fans storm the court—plus, the stories of people jumping up and down and driving through the streets honking their horns or running up and down the halls of their apartments shouting.

Stein: Even though Utah was clearly on the downside, winning a road game, a Game 5 road game, at Utah, was still inconceivable. Down 17 in the fourth quarter—I mean, that was still unfathomable that they could come back and win that game.

The Mavericks, led by the Big Three, were an entertaining group that had a reputation, thanks to its over-reliance on offensive firepower, for faltering in the playoffs. It changed at least part of that reputation (while reinforcing the other part) in the 2003 playoffs, a dramatic run that ended when Nowitzki injured his knee in the third game of the Western Conference finals against the San Antonio Spurs. Prior to that, however, the team played what is, perhaps, the signature game of the Nowitzki-Nash-Finley era: Game 2 of its semifinals series against the Sacramento Kings, a lights-out shooting display that saw the team score 83 points—in the first half.

“Would we have won a championship? Of course. Why not? I mean, you never know. I think it would have been interesting.”

Nowitzki: They scored, like, 60—and they were still down 20 at the half. It was amazing. It didn’t matter who really shot it; it went in. It was fun. And actually, Sacramento accused us of running up the score, which was total crap. You’re out there in the playoffs. You don’t try to run up the score; you’re trying to win. You never know what can happen in a playoff game. That was a fun series.

And even the series before, I’ll never forget: when we’re up 3-0 on Portland, and they run three straight on us, and we have to go to Game 7. You don’t really know what can happen in a Game 7. I’ll always remember that year. That playoff run was a lot of fun. But to go seven in the first round, and seven in the second round, and it should have gone seven in the third round—we were up, I forget, 16 or 17 going into the fourth quarter, and then Steve Kerr just made all of those threes. That was a fun year.

Nowitzki’s injury, a chance knee-to-knee collision with Spurs guard Manu Ginobili, began the dissolution of the marriage between Cuban and Don Nelson.

Nowitzki: Before Game 4, I was down there working up a sweat, because Nellie wanted to see how I was moving. And I was moving pretty well. Cubes was out there, too, and Cubes wanted to let me play. He’s, like, “Let him play.” Nellie was, like, “He’s too young. I wouldn’t risk it.” I think that’s where it started, where they went separate ways. After that, years later, obviously it got very ugly. But that’s the first time where they weren’t agreeing on some stuff.

Stein: I don’t think there’s any question that Cuban and the doctors thought he could play, and Nellie was just not going to play him no matter what. Now I’ve asked Dirk about it 15 times, and Dirk to this day, says, “I don’t think I could have played; I think it would have been a mistake.” So, he hasn’t changed his position on it.

Nowitzki: Even just standing up during the game, I could feel that my knee wasn’t right. Now, if we had made it to the Finals, then I probably would have suited up and played, because I would have had a couple more days. We lost in Game 6, but if we won we would have had a Game 7; that would have given me probably an extra week before the Finals.

Though the team seemed on the edge of a breakthrough, a year later, that version of the Mavericks was already in the midst of being disassembled. Nash signed a free agent contract with the Phoenix Suns in 2004. Nelson resigned as coach near the end of the 2004–05 season. Finley was released (and later signed with the Spurs) in the summer of 2005. But Nash, of course, was the departure that stung Nowitzki the most.

Nowitzki: I told Steve the day before he actually committed, I said, “Now you actually have a family to look after”—he had the two kids on the way—“if it’s that much more—if it’s just a couple million, then you could stay—but if it’s really that much more, and a year more, then you have to do it.” I think I was the first call he made after he committed, so I guess that shows how close we really were.

Cuban: Dirk and I just had honest discussions of all the details. Dirk understood that we made a great offer, but the Suns made a better offer. That’s the way the business works.

Nowitzki: There will be some decisions you don’t like, and there will be some decisions that you like, but you can only control yourself. That’s how I’ve looked at it the last couple years.

Stein: The general consensus in the NBA is they got better without each other and they grew without each other. They were more assertive without each other. I don’t buy any of that.

Nash: Would we have won a championship? Of course. Why not? I mean, you never know. Keeping me in Dallas wouldn’t have really affected their salary cap situation. They still would have been able to bring in the other guys they brought in, for the most part. I think it would have been interesting.

Nowitzki: We text a lot these days. You know, he’s got a lot going on. He’s got his two kids.

Nash: My daughters call him Uncle Dirk. They know he’s an important person to me. They can pick him out on a TV screen.

For the first time since he arrived in the United States, Nowitzki was forced to find a new running buddy, on the court and off. Through a series of roster moves, the team presented him with a possible alternative: Jason Terry. Their first season together was turbulent, remembered most for an on-court argument during the deciding game of a second-round series against Nash’s Suns, after Terry allowed the former Maverick to hit a game-tying three-pointer.

Jason Terry, Mavericks guard, 2004–2012: I was coming into a new system, trying to replace a guy that was pretty much the franchise, you know, an MVP point guard in Steve Nash—and Dirk’s best friend. It put a lot of pressure on me. The things that happened with me and Dirk brought us closer together. It was a situation where we’re both competitive; we all want to win. I messed up on an assignment, and it cost us a second-round series. It was a long summer for us. But we came back that next year. We started to work out together. We’d go to dinner. That brought us closer together. We’re good friends now.

Yeah, my daughters love him, too. “Mrs. Nowitzki”—that’s what it reads on Jalayah’s door when you go to her room. She would leave him notes after games. She’d leave him little notes. Like, “I love you, Dirk” and “Have a good game.” Stuff like that.

A New Level, A New Low

With Nash gone and new coach Avery Johnson at the helm, Nowitzki was pushed into a role to which he was unaccustomed: team leader. Not one prone to speeches, Nowitzki could lead only by example. That led to one of his most iconic moments in a Mavericks uniform: the three-point play that sent Game 7 of the San Antonio Spurs series into overtime, when the Mavs won, advancing them to the Western Conference finals again and, later, the franchise’s first NBA Finals appearance.

Terry: If you go back to previous playoffs series, everybody was questioning his toughness. Can he get it done? Does he want the ball in the clutch? This was a situation where, we’re in the huddle, and Coach says, “We’re coming to you, big fella.” You could see it in his eyes: just a determined look that guys hadn’t seen before.

Nowitzki: Avery was like, “If you ever get in this position, there is so much time. Drive it to the basket. Anything is possible.” So coming out of that timeout, I knew that there was still a lot of time left. I wasn’t going to just force a bad shot. I was going to drive in there, get a quick two, maybe kick it out if Jet or somebody is open, get a good look at a three. I was actually trying to dunk it. I was going to go in there and dunk it, and then quick foul, probably. And I saw Manu all of a sudden in the lane. I thought he was going to let me go and dunk it, maybe. But he jumped up with me. I tried to go as hard as I could. Kind of laid it up. Lucky bounce.

[giflike_video id=”1″ /]

Darrell Armstrong, Mavericks guard, 2004–06; assistant coach, 2008–present: We already knew he was going to make the free throw. It was just that quick. We lost the game in two to three seconds. And another four or five seconds [snaps fingers] he got it right back. That’s the way big game players do it. He wants the ball in this situation, you know—I love that.

Nowitzki: That was definitely one of the greatest plays that I’ve made for this franchise.

Despite Nowitzki’s heroics against San Antonio and his 50-point game against Phoenix in the Western Conference finals, ultimately the Mavs fell in the Finals to the Miami Heat. It was a gutting loss, since the team was up two games in the series and was well on its way to a third when the bottom fell out. It was Nowitzki’s lowest moment. “Nothing else is even close,” Cuban says. “We had it, and it was taken from us.”

That disappointment, though, pushed Nowitzki to new heights of personal achievement, directly leading to his league Most Valuable Player award after the 2006–07 season.

Al Whitley, Mavericks equipment manager, 2001–2018; now special assistant to the owner: He needed some time to get away, which he did. Took a trip overseas with Holger and tried to sort some things out, but he came back motivated like all the great ones do. It was time to get back to work and make sure that never happened again and he could eventually hoist that trophy.

Casey Smith, Mavericks head athletic trainer, 2004–present: From an overall standpoint of how he approaches things, how he takes care of his body, his nutrition—the guy that most closely resembles him that I’ve ever worked with is Kobe Bryant. There is a lot of respect around the league from a player’s standpoint for Dirk. It’s funny to listen to the media. The media will be like, he’s this, he’s that, he’s not this, but players around the league realize the amount of work that he’s put in, and they know how tough it is to stop him. There is definitely a healthy respect there.

Terry: Coming off a Finals loss, all of us were pretty much locked in, but he took his game to another level. It wasn’t that he averaged more points. It was his all-around game: more rebounds, more assists. That’s what took his game to another level.

Smith: He’s a guy that when we lose, whether it’s a game or a series, he figures there is something he could do better. It’s never just, Oh, well, it didn’t happen. So he was trying to rehone his nutrition, trying to evaluate his workouts, trying to evaluate his daily things. “What could I do better, what could I do different to get us those two more wins? All we needed was two more wins.” He definitely had a feeling of something uncompleted.

Stein: I did not really expect the MVP season, and not as a slight to him. I think the thinking was that the whole team was just not going to be able to recover from that Finals loss.

“He was looking at his phone and he got a text and he was just kind of, while staring at the ceiling, he said, ‘I got it.’ And I’m like, ‘What? You got what?’ And he says, ‘I got the MVP.’ He was just sheepish about it.”

They didn’t; it just took awhile to figure that out. Though the team blazed through the regular season, it only set them up for a bigger fall. The No. 8-seeded Golden State Warriors, coached by Don Nelson, knocked off the Mavericks in an unprecedented six-game series. Suddenly, Nowitzki was left with an MVP trophy that didn’t feel very valuable.

Stein: They were so dominant that next season, it just made the Golden State thing 10 times worse.

Nowitzki: I wanted to leave. I wanted to get out. But the league wouldn’t say anything. I only found out maybe three days before the press conference. They wouldn’t tell me earlier. Everything was so fresh. I felt embarrassed, I think, more than anything. We won [almost] 70 games, and all of a sudden, we’re a first-round exit. First couple of days, I just thought: Don’t give it to me.

Brian Dameris, Mavericks former director of business development; longtime friend: I was at his old house and we were kind of just lying around, hungover after one of our bender nights trying to get through the sorrow of what had happened, and he was looking at his phone and he got a text and he just kind of, while staring at the ceiling, he said, “I got it.” And I’m like, “What? You got what?” And he says, “I got the MVP.” And he had gotten a text from someone at the league telling him he’d won, and back then you got the award before the second round in front of the fans and that wasn’t going to happen. He was going to have it in a small room in the AAC in front of the media, and I jumped up and I was like, Oh my gosh! as I kind of finally realized what was happening. I was trying to get him excited and he was just sheepish about it.

Smith: At that point, it’s such a hollow award for him. If you can imagine someone that competitive having to go do media and press conferences and stuff about that award when professionally and team wise we just had the biggest disappointment and letdown. That’s such a backward way to have to do things. But you really have to be kind of the most professional you can imagine to go forward and do the media and put on the team face and bear the brunt of all the team’s failures by yourself, because you’re the only one still in the media.

Nowitzki: Looking back at it now, it was obviously a great, great honor. I can always say I was the MVP of the greatest league in the world.

A Fresh Start

At the trade deadline in 2008, the Mavericks brought in future Hall of Fame point guard (and former Maverick) Jason Kidd. It was not a panacea for the haunted team’s troubles; Avery Johnson was still fired after the season. But the trade did wonders for Nowitzki.

Nowitzki: We lost the Finals, and then a first-round exit the following year, and then that next year we were struggling into February. I kind of felt like, I think everybody felt like, we needed a change. When Kidd came, he just made the game a lot easier. I felt great with him. I had fun again. I was running. I got open looks again. What he’s so great at, he sees stuff developing. With other point guards, you’d get the ball once you were open, and once you get it, they’d already closed out. Well, he already sees that, hey, this guy might be open, so the pass is already on the way—when you might not be open yet. But it comes to you right when you’re open, and you’re open for that split second.

Kidd: It’s easy. You’ve got a guy that wants to pass, and you’ve got a guy that wants to score; it doesn’t take long to mesh. He makes the game so easy for everybody that’s out on the court because he draws so much attention. You’re going to get wide-open looks.

Also helping Nowitzki was his new coach, Rick Carlisle. After he was hired, Carlisle went to Germany to do his homework.

Rick Carlisle, Mavericks head coach, 2008–present: I wanted to get a chance to see where he was from, spend some time with him and his family, see kind of culturally what his background was, who he was as a guy from his town and not as sort of a transplant in Dallas. It was great. There were some things that were surprising to me. I was surprised at the facilities over there. One of the gyms that he worked out a lot in when he was coming up through the ranks had a linoleum floor. It showed me that if you have the ability level and have a passion and a desire to be great, you can be a great NBA player no matter where you come from. The trip was fruitful, personally and from a basketball standpoint. I just got a better grasp of who he was.

Dameris: I think Rick brought the best of what Nellie did and what Avery did together to make him the well-rounded player that he is, and on a personal level, I think as he got confidence because he was playing better, he got more swagger in the locker room.

Led by a rejuvenated Nowitzki, the Mavs won a surprising 50 games in 2008–09 and knocked off the archrival Spurs in the first round of the playoffs. What happened next was the strangest stretch of Nowitzki’s career, finding him in the media’s crosshairs for wildly divergent reasons.

An innocuous remark about how the Denver Nuggets were defending him with Kenyon Martin and Chris Andersen somehow turned into a made-for-TV controversy. NBA on TNT studio analysts Charles Barkley, Kenny Smith, and Chris Webber publicly and loudly questioned Nowitzki’s bona fides as a truly elite player and team leader.

That was nothing compared to what happened next: Nowitzki’s fiancée, Cristal Taylor, was arrested at his home and, from jail, claimed to be the mother of his unborn child. (She was later extradited to Missouri, where she was sentenced to five years in prison on fraud charges. And, as it turned out, she was not pregnant.)

Barkley: First of all, I feel like we were 100 percent right. Anybody who’s ever met a great player knows we were right. You never give credit to the defense—ever. Never heard a great player say that.

Nelson: Look, there’s lots of competitors: there’s Björn Borg, and the way that he kicked butt and was gracious and always said the right thing; and then there was John McEnroe, that smashed cups and hit tennis balls into the stands. Now, are you going to tell me that one way is right and the other way is wrong? When he states the obvious, gives the opponent what all of his coaches know—that they’re playing me like this, that, or the other, or they’re doing a nice job doing this—he’s not saying that he can’t kick your butt.

Stein: What he played through in the Denver series is ridiculously off the charts. To have that all be played out in public, and the way he played, getting very little help, Josh Howard injured—he played as well as he’s ever played. I don’t know what more he could have done.

Nowitzki: Really, any time is a bad time for stuff like that. But I think it was good for me that we still were playing, and I was able to concentrate on the stuff that I love to do, which is playing basketball. In the morning for an hour in shootaround and at night for two-and-a-half hours, I could escape a little bit, hang out with the guys in the locker room.

Kidd: I think it just showed his character, and him being a professional. That’s just the person he is. It doesn’t matter what’s going on outside those lines.

Terry: His teammates really took that to heart. That’s why he’s the leader of this team.

Nowitzki: [After I went back to Germany], I took everybody—my sister, her kids, her husband, and my parents—and we went to some island. Went to a resort. It was very quiet. Got some beach time. Talked to my family a lot, because obviously they were not here when it all went down. They had a lot of questions. We had a lot to talk about. Already after that two-and-a-half weeks’ vacation, I felt a lot better.

Despite that embarrassment, as his first decade in Dallas ended in 2009, Dirk Nowitzki had accomplished more than anyone could have imagined when he arrived. If he had retired then, his legacy was already secure, having done nothing less than save professional basketball in the city.

Stein: He’s definitely one of those few guys who you could see finishing his career with one team. I think he would like that. And he’s said it, and knowing the way he is, I believe it. You know, going somewhere else to win a championship as a contributor wouldn’t be the same; he wants to do it here because of the ups and downs here. I think he really wants to try to do it here.

Nelson: If you look back and point to when we got here, I mean, it was what? It was a 10-year walk in the desert with no playoffs? And as soon as he kind of got through his period of time where he’s not a rookie or sophomore, and he started becoming the Dirk we know and love, you know, we’ve averaged 50 games and been to the playoffs every year, went to the Finals one year. So yeah, I think people appreciate what they have in Dirk. I can’t speak for every fan—I mean there’s no way I can do that—but I think true basketball fans have understood what he’s done for this franchise.

But the best was yet to come.

Part 2

That Championship Season

The summer of 2010 was a momentous one for the NBA. Three members of its celebrated 2003 draft class—LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, and Chris Bosh—were all unrestricted free agents for the first time, available to anyone with the right contract, and every team in the league had been hoarding salary cap space and honing its pitch for years, hoping to convince one of them to sign. The Mavericks’ plan was to use the expiring contract of lumbering center Erick Dampier to trade for James, or Wade, or Bosh, or maybe even Atlanta guard Joe Johnson. Whomever would agree to come.

But, first, the team also had to take care of another free agent: Nowitzki.

He had opted out of the last year of his contract and, though he turned 32 in the weeks before he could sign a new one, Nowitzki would have been happily welcomed on any NBA roster. Given all the disappointment he had endured with the team—the Mavs had won just one playoff series since the 2006 Western Conference finals—it wasn’t a sure thing that he would come back. The Los Angeles Lakers, coming off back-to-back NBA titles, had made their interest known, and there were other suitors, all of whom could have given Nowitzki the chance to compete for a championship. That’s all he wanted—a chance.

The Mavs had methodically remade the roster since 2008 in an effort to give him that, trading for Kidd, do-it-all forward Shawn Marion, and two-time All-Star Caron Butler. Along with holdovers Jason Terry and J.J. Barea, they gave Nowitzki his best supporting cast since the Big Three days. Maybe no one wanted to put much stock into the team’s chances, after repeated letdowns, but the pieces were in place. Most of them, anyway.

And, so, while James, Wade, and Bosh decided to join forces in Miami, Nowitzki came back to Dallas.

Nowitzki: When I sat with Mark in his office in 2010, I said, “OK, we’re going to—we’ll try this four more years and I’ll sign that four-year extension of contract.”

The Mavs had two more moves to make. Over the summer, they traded Dampier for center Tyson Chandler, a former lottery pick known for his defense. And then a less heralded addition: just before training camp began, they signed veteran role player Brian Cardinal. Chandler was an ideal complement to Nowitzki on the court, and Cardinal became a good friend to him off of it.

Brian Cardinal, Mavericks forward, 2010–2012: I’d never really had any conversations other than him talking smack to me. And so when I first met him, damn, I was in awe, just because it’s Dirk. It’s the man. You try to compete against him and you just realize you’re just up against the biggest challenge ever. And so I was excited to meet him. I was excited to be a part of the team and try to make the team. And he was great from the beginning because we got paired together during shooting drills and different things, and we would kind of fool around and have a good time.

And I still remember, a week or two into training camp, he organizes a bunch of guys to go to a Rangers game and he invites me, and I thought that was the coolest thing ever. Just because I had just met him for two, three weeks, and he’s already including me. He doesn’t know me from anybody and—but that’s just the kind of guy he is. Just kind of an inclusive guy and wanting to bring me into the mix.

So we went and had an absolute blast. I remember I called Danielle, my wife, on the phone in the shuttle bus that we were in, and I’m like, “I’m on my way to the Rangers game. I cannot talk. This is incredible.”

Tyson Chandler, Mavericks center, 2010–2011, 2014–15: I watched him lose in that Finals. I watched Miami celebrate on that floor. I watched him walk off. I watched all those things, and so I understood where he was at in his head mentally, and I wanted to help him get past that hurdle.

Dameris: It’s just about adding a piece, adding a piece, and finally Tyson was kind of that perfect partner for Dirk, because he could do the rebounding and the dirty work that we wouldn’t want Dirk to do as a power forward.

Shawn Marion, Mavericks forward, 2009–2014: We knew we had something special when the season started.

Despite losing Butler halfway through the season to a knee injury, the team still won 57 games. (They mostly replaced Butler with Peja Stojakovic, their former nemesis with the Kings and Hornets.) But Nowitzki and the Mavs had had plenty of great regular seasons before. In fact, they’d won 55 games the previous season and didn’t even make it out of the first round of the playoffs.

Nowitzki knew he couldn’t waste many more opportunities, and this was his best in a long time, probably since 2006. Besides, looming on the horizon was a superteam in Miami.

Chandler: You could be on a championship team one year and then you could never ever be on a contending team again in your career. It’s that fine, and I think Dirk understood that, especially going through the first Finals.

Nowitzki: Honestly, I thought we’re going to go to the Finals for years here on out. After you go to the Finals one year, you win [almost] 70 the next, you’re thinking, “Hey. We’re a great team and we’re going to be here for here on out for next couple of years.” And then it’s kind of taken away from me, like that.

Chandler: I think he realized that we had a complete team and this was his one real shot to really go after it, and he did that. He was so locked in that entire season and especially when it came to playoffs, there was such an intensity around him. He’s not an intense person, but you felt it. You felt how important it is, you felt how locked in he was. And that in itself—I felt like every other guy, you know, you got to do your part. Look at this man, look at what he’s doing, look at how he’s driving himself. You just have to do your part. I remember I wanted it so bad for myself, and I wanted it just as bad for him, because I was a fan of his. I’d never seen anybody like that in my career. He was just in such a zone.

Marion: He would give everybody a look and you could see it in his eyes.

After surviving a brief scare in the opening round against Portland, blowing a 23-point second-half lead that brought to mind previous playoff collapses, the Mavs swept Kobe Bryant and the defending-champion Lakers and got past the upstart Oklahoma City Thunder in five relatively painless games in the Western Conference Finals. Waiting for them in the NBA Finals was the Miami Heat.

Narratively, it seemed perfect: a second chance in the place where it had gone so wrong in 2006. They would even be facing Dwyane Wade again. But Wade and little-used forward Udonis Haslem were the only remnants of the 2006 squad.

Cuban: That was a completely different set of circumstances.

Nowitzki: After ’06, we were so disappointed with Miami and we would love to get a chance again, but then ’07 happened. We won [almost] 70 games. We didn’t get back. Then we did the [Kidd] trade, ’08, I think we lose early; ’09 lose to Denver. By the time we got finally back to the Finals in ’11, I would have played a team from Siberia or something. So, it was a battle for us to even make it back in ’11, and it was, to us, it was a great side thing that we happened to beat Miami again. But for me, I wanted to have tunnel vision. Who knows? It might be your last shot at getting that thing and getting to the Finals. I would have played any team in the world.

Smith: I don’t think anything can take away the feelings of 2006. But I don’t think Dirk wins MVP in 2007 or 2011 happens without 2006 being such a colossal meltdown.

In the Finals, Nowitzki led a 22-5 run in Game 2 that concluded with a driving, game-winning layup, and then fought through flu-like symptoms that began before Game 4 to put the Mavericks up 3-2 going into Game 6 in Miami. James and Wade were caught on camera mocking his illness, questioning if he was even sick. “I think it is understated how being in that situation drove him in that moment, at least in my opinion,” Smith says.

He didn’t need much more motivation. After five frustrating years, Nowitzki was in position to win his first title. But nothing was going right.

Cuban: Dirk was, like, 2 for 11 from the field.

Cardinal: I think, in Dirk terminology, it was brutal in that first half. And tensions are high. There’s a lot of nerves. There’s a lot of everything going on. I mean, just how enormous that moment is. And I’ve always been one to just kind of screw around. Screw around in a good way. Try to take some of the edge off, and what I’ve found is a lot of times when I’m able to kind of interject or do something, it does kind of let their guard down a little bit so they can appreciate that moment.

And at halftime, we’re all trying to figure it out. He’s trying to figure out how to play a little better. We’re all trying to remember how we can win this game and win the championship, and I still remember going in the locker room and trying to pump everybody up and give them high-fives and talking to them, saying, “This is right where we want them.” And I remember going up to Dirk and saying in front of folks, “Hey, I love it. I love it. You’ve got them right where you want them. You’ve got all your misses out of the way. There’s no way you’re going to shoot that bad in the second half.” Just trying to gas up the situation. He looks at me, he’s like, “Dude, you’re nuts. You’re nuts.”

Cuban: You could see him come out of the locker room ready to make up for it. And he did.

Cardinal: Honestly, I have no idea if what I said helped impact anything, but my goal was just to have him relax. Have him calm down a bit, so hopefully for one split second, he’s thinking about me being a knucklehead and not worrying about the game.

Nowitzki scored 18 points in the second half and the Mavs won 105-95. He was named Finals MVP.

He had to come back from the locker room to retrieve his trophy because he had fled the court after the buzzer sounded, too overcome with emotion and too private to share it.

Whitley: It was incredibly surreal for him and an incredible weight off his shoulders. You know, this great European player that could never lead his team to a championship. All of a sudden, that stigma’s gone.

Then it was time to celebrate.

“Honestly, I thought we’re going to go to the Finals for years here on out. After you go to the Finals one year, you win [almost] 70 the next, you’re thinking, ‘Hey. We’re a great team and we’re going to be here for here on out for next couple of years.’ ”

Skin: I know they’re partying somewhere, and so I texted [Mavs play-by-play man Mark] Followill, and he says they’re at this club LIV, it’s Lil Wayne night. I got there, there’s a line wrapped around the building, and it’s a $100 cover.

So I do the douchiest thing I’ve ever done in my life. I walk up to the front, I walk up to the security guard, and I go, “Hey, man. I’m on the Mavs broadcast, and I’m supposed to be in there right now.” And he looks at me, and—I swear to God—I googled myself and showed him a picture. So he lets me in. I go in, it’s a fucking madhouse. The back part of the club, it’s roped off, and it’s happening in there. And I’m like, I’ve got to be in there. That’s where I’ve got to be. How do I fucking get there?

Well, there’s this staircase, and on the other side of this staircase it has a landing, so I look underneath the landing and I can see legs, and I can see light coming through. I’m like, I’m going to go through there. I got on my hands and knees and I crawled over there. I swear to God I crawl up onto Holger. Holger is wet, he’s covered in Champagne, he’s wearing a Members Only jacket, and I think he’s crying or there’s Champagne, I don’t know.

I crawl past him, and I stand up on a platform, and I’m standing next to Dirk. I’m standing right fucking there. So I stood there for three-and-a-half hours, I was not going to go anywhere.

Ian Mahinmi has these glasses, he gives them to Dirk, Dirk’s wearing them—oh my God, it was incredible. That $86,000 dollar bottle of Champagne starts going around. Dirk takes a big swig.

Cuban: My AmEx initially got turned down by their fraud detection, and I had to go to the manager’s office and ask them if they were watching TV tonight and did they see the game. Finally got a manager who did see it and approved the bill.

Nowitzki: We had a great crew of guys that I loved: Tyson and J-Kidd and Jet and, I mean, J.J., Peja coming on late, and I love Cardinal. All these guys, I’ll always remember them and the crew that we had. The Trix [Marion]. The fun we had on buses and just really getting hot at the right time. Starting to play our best basketball at the right time. I will always remember when we won it. The night in Miami. The coming home. The parade. That stuff will always stick with me.

Cuban: Dirk put all he had into the Mavs. I was so happy for him. He had dealt with so much that it was an experience that I didn’t want to end for him.

The Wilderness

Before Nowitzki could go about helping the Mavericks defend the title, he had to deal with a 149-day lockout as NBA owners sought to rework the league’s collective bargaining agreement again. When the season finally began on Christmas Day, the team was different, largely because Cuban was worried about the implications of the new salary cap rules.

Stojakovic and playoff hero DeShawn Stevenson were gone. Butler and Barea were gone. So was Chandler, off to the New York Knicks, where he would help propel them to more than 50 wins while winning Defensive Player of the Year.

It was an odd season in which the Mavs simultaneously seemed to be better and worse than they were. They still had Nowitzki, and he was still at the top of his game.

Nowitzki: We got swept by the Thunder, who happened to go to the Finals that year, but we actually almost should have stole both games in OKC. One we lost at the buzzer, with [Kevin Durant]. But we were thinking, Man, we got them right there. And then we come home and lose and have no shot, basically, in Game 3 and Game 4. But that was still a decent team. Obviously, we had lost Tyson and some of the guys. But, yeah.

That was the last time Nowitzki and the Mavericks were thought of as contenders in a real sense, and that was more as a courtesy to their status as reigning champs and the presence of their leader.

There would be some fun teams after that—the 2012–13 squad that grew beards as they battled to reach a .500 record for the season—and there would be some intriguing teams—the 2014–15 version that featured mercurial point guard Rajon Rondo, Uptown legend Chandler Parsons, and the delightful Monta Ellis—but nothing the league had to take too seriously.

Skin: It has been seven years of forgettable basketball. Besides Dirk passing individual milestones, what are the best team moments? [Almost] beating San Antonio one year. That was, like, the best.

Nowitzki: San Antonio really breezed through the playoffs after us. We forced them to a Game 7. We’d had our chances even to win. I forget which game it was, but [DeJuan] Blair got kicked out at the end, and then we ended up losing that home game. If we win that, I think we’re up 3-1 then. I can’t really remember how that went down, but that was a fun series against a great team and they ended up winning the championship in a breeze. So we had some good teams, too, but just not back to the championship level where, if you win a championship, you smell that. You feel that feeling, the parade and everything. You get caught up. You kind of want it again. You want to make it happen again. You want to see that excitement in the city. It was just never, never quite back up there again.

It wasn’t for lack of trying. Every year it seemed there was the hope of a top-tier free agent coming to team up with Nowitzki—Chris Paul, or Dwight Howard, or maybe both!—and then it wouldn’t happen and they had to do their best with a backup plan, and sometimes the backup to the backup plan.

It was just enough, when combined with the future Hall of Famer on the roster, to be good. But, eventually, that didn’t work anymore.

Skin: The irony is, the Mavericks got their first championship beating a superteam, and then the Mavericks fell in a ditch and couldn’t get out trying to build a superteam.

Smith: I feel that it has been a strange journey for him since [winning the championship]. Unable to land top free agents or just not having a very good team.

Nowitzki: Obviously, we went through some really tough years the last two years. But sometimes, like I always say, we went over 10 years of 50-games-plus [wins]. You know, it’s just the cycle sometimes. You’ve got to reload. Besides, really, the Spurs, everybody in my 20 years went through some downs and came back and some downs and some ups.

Dad Nowitzki

It was somewhat easier for Nowitzki, such a fierce competitor for so long, to be philosophical about the fortunes of his team. He had the championship trophy, yes, but then he also had a wife and family.

Jessica Olsson actually came into his life before the NBA title. Born to a Kenyan mother and Swedish father, Olsson was working in Dallas for the Goss-Michael Foundation art gallery when they met. Like Nowitzki, she also comes from an athletic family—her younger twin brothers, Marcus and Martin, both play professional soccer in England.

It’s probably no surprise that Nowitzki had the best year of his career after they started dating.

Nowitzki: We met actually at a charity thing. She was on the board of that charity thing. I think it was around the All-Star Game, and the All-Star Game was here in Dallas. I went there and I knew her boss and started talking a bit. And the rest is history. We met in 2010. We were married in 2012. Our daughter was already born in 2013. So it’s been a great seven years of marriage with three kids already, and we are busy.

Lara Beth Seager, event designer and producer, Dirk Nowitzki Foundation: I tell him all the time, she is just the biggest blessing that ever happened to him because she is the perfect helper to him and the perfect wife and the perfect mate for him. They are going to go great together. She is so poised and polished and genuine. She is the perfect complement to him, and I mean that in all sincerity. Those are not made-up words. They are truly two great people that deserve each other.

The Nowitzkis had daughter Malaika in 2013, followed by sons Max and Morris in 2015 and 2016.

Nowitzki: I think the step up from two to three was a lot. You know, when you’re outmanned. I mean, I’m sure everybody says that. But you can’t get ready for anything unless you go through it. You know? Everybody says, “Hey, one kid is a life change.” But until you experience it, you don’t know what’s coming, so kids is definitely an unbelievable blessing, and they’re all healthy and I can’t complain. But it’s definitely busy at times.

Marion: Kids are a handful. Kids will do that though. So, like, I got one, if I had three I could see I would definitely be busy all day. You try to do what you can to survive.

Whitley: He was a little more tired with the kids, trying to be a father, and a husband, and still be one of the best to play the game. He got a little more grumpier on the early-morning practices and stuff like that.

Nowitzki: We almost had, by the time we had the last one, Morris, Malaika was almost just barely getting out of her diapers, so it’s like almost having three in diapers at the same time. It was challenging and, you know, we have no family around here. My family’s still in Germany, and most of her family is still all over the world.

Cuban: People don’t realize that Dirk wanted a family as much or more than a championship.

Dameris: He’s been wired that way to want to settle down and have a family, and now that he is, I think he’s realizing that, and we’re seeing it in how much he’s enjoying his retirement so far, that he’s not somebody that will have to jump back in the game because they missed that. Their life is just consumed by it and they miss that competition so much that that’s really all their life was. He realizes that he can have a well-rounded life.

Smith: It has been a huge change for him. For literally all his adult life, basketball was first and he filled in around that.

Dameris: He was a guy that didn’t really have hobbies. Literally didn’t enjoy anything but watch hoops and practice, so I think it’s been great in terms of really showing him, and you’re seeing this now, he wants to travel with kids and show them the world and all he can before they really have to go to school full time.

Nowitzki: I speak German with them. I try, and then wifey speaks Swedish with them, and, obviously, everything else is English. So, English is really all they fluently speak, and, I mean, they understand Swedish and German when we tell them something, but it’s always English back. So, you’ve really got to force yourself. “Hey, you know. Do that again and say that again.” Sometimes they say, “What?” And then you’ve got to say it again and explain it in English. Sometimes it’s really hard. I actually thought it would be easier to raise kids multilanguaged.

Passing the Torch

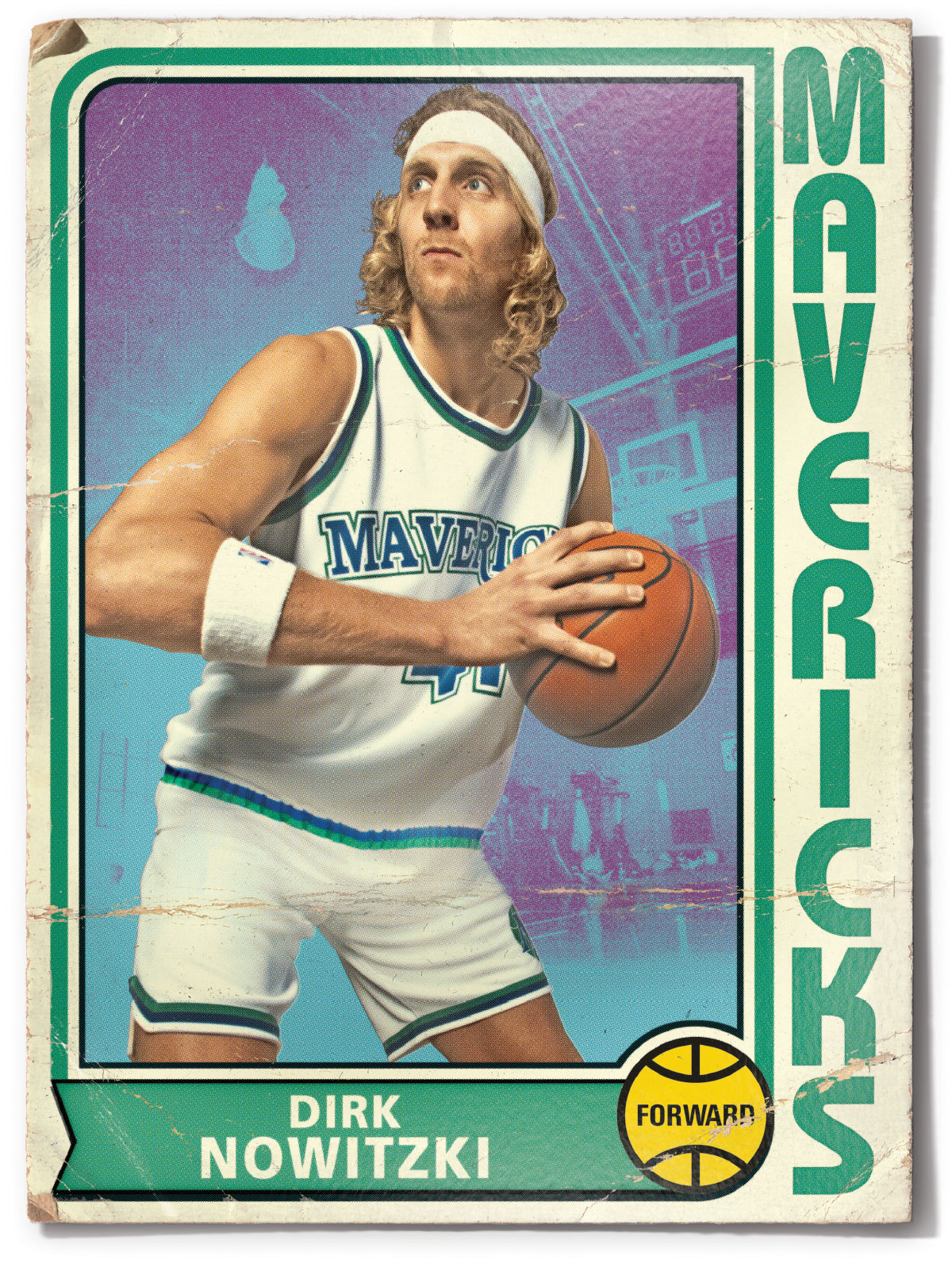

As his career neared its end, Nowitzki was surrounded by kids on the court, too. Luka Dončić, for example, was born a month after Nowitzki made his NBA debut. One of those young players, Maxi Kleber, was also from Würzburg and had met Dirk when he was 12.

Maxi Kleber, Mavericks forward, 2017–present: Somebody knew that he’s working out right now in the summertime, so friends of mine and my brothers, we went to that gym because nobody knew but us, for some reason. I don’t know why. And we waited there for 1½ hours, two hours. We weren’t even sure if he was in there, but then he came out and we were so excited. We got a picture with him, we got to talk to him, like, only for three minutes, but, you know, it made our day, probably like our year. I still have the t-shirt, the ball and those papers signed from him from back then. This was like a very special moment. You remember those things.

To be on a team with him is unreal, because, thinking back, I would’ve never imagined to play on the same team with him because there is only a certain amount of years you can play basketball, but Dirk somehow managed to play for 21 years in the NBA. He played before, too, but it’s pretty amazing especially you know, he basically made it possible for me to team up with him. And the first time I came here, I also remember that it was like I was standing in the gym, it was so unreal. I went to lunch with him the first day when I got here and I couldn’t really believe it. I was kind of holding back, I didn’t know what to say and it was crazy unreal for me.

Kleber wasn’t the only young player who had to get used to treating a legend like a colleague. But even veterans benefited from seeing Nowitzki up close.

Zaza Pachulia, Mavericks center, 2015–2016: One of the things that I am still using is amount of time he took off after the season. He called me one week after our last game and asked me to meet in the gym. I was surprised, but he explained to me that older you get you can’t rest long period of time because it’s hard to get back in shape for older players, and you have to keep the motor going. I am using that approach now, and it’s been helping me.

Nowitzki’s old partner Tyson Chandler came back for a season in 2014.

Chandler: Man, being around him and watching him and watching how diligent he is with his routine, watching his day-to-day work, knowing exactly when Holger is going to come into town, when it’s time for him to rev it up, just knowing his entire schedule … Like, I hadn’t personally been around anybody that diligent in my career. Watching his work ethic, watching him attack his weaknesses as well as continue to maintain his strengths was inspiring to me.

Being around other athletes like that helps you sharpen your tools, and when I came back I just got that much more motivated to sharpen my tools to be the best player I can be to play alongside this dude, and that’s what he brings out in guys. If you have any pride, and if you have any type of like real love and passion for this game, and you’re around a guy like that, you can’t help but elevate yourself, and that’s what he’s done.

The End

Nowitzki had slowed down his last few seasons, but he still managed to stay on the court, thanks to help from Smith and his own drive. In his 20th season, he played 77 games, before sitting out the last week of the season to have ankle surgery. He was supposed to be ready for training camp, but a setback delayed his return until December 13 against the Phoenix Suns.

After he was back, though there was the occasional flash, his impact was dramatically reduced. It was nice to see him pass the baton to Luka Dončić, and he eventually managed to pass Wilt Chamberlain for No. 6 on the all-time scoring list. But he hadn’t been so ineffective since his rookie season. He ran like someone banged on his front door in the middle of the night and he jumped up from a dead sleep to see who it was.

Even though he waited to make a formal announcement, it was clear the end wasn’t just near. It was here.

Smith: The rehab and recovery was definitely harder than anyone would have liked. That’s the thing about medicine, we like to think it’s all black and white but in reality it is all completely gray.

Whitley: I mean, to his credit he didn’t talk about it much. To see what he had to put into each day in preparation, just to practice or to play. The extra treatment sessions and therapy and what have you, you could tell he was giving everything he had to get on the court and play every night. To be honest with you, I thought after 20 years he might have called it a day. Just the perfect number, but I give him all the credit in the world to keep that desire and that passion to keep playing at this level, and the work it takes especially at his age that you have to put in to play at this level, it’s an incredible accomplishment in itself. I was going to be happy with any decision he made because his career is so storybook.

Nowitzki: It’s just the foot gave me problems all the time, even in good games. At times in the second half, I’d make a shot and I’d come down and it would be shooting in my foot. It just wasn’t fun anymore. You know? Unfortunately.

Smith: The effort that it took to prepare and the inability to perform consistently made me feel that throughout it was definitely his last year.

Even in a diminished state, he continued to lead by example.

Dwight Powell, Mavericks forward-center, 2014–present: I know he spent countless hours just trying to physically get ready, and then from there getting traditionally ready and reintegrated back in things. It was tough because I know he wanted to be out there as soon as possible, and spend as much time on the court with us if he could, but I was really happy to see him do what he did, especially his last of games. I mean, that just goes to show his greatness.

Devin Harris, Mavericks guard, 2004–2008, 2013–2019: Just to watch him fight and get back and the injury, the working out, the day-to-day stuff, the dieting, knowing—I’m guessing he knew it was going to be his last year. We didn’t particularly know, but to just get back there for one more ride, it was great to see. Him getting out there and playing well.

Nowitzki: I think mentally, I could do another year. Especially with [Kristaps Porzingis] coming back, it would be exciting time for me to be there. You know? Just try to help wherever I can, but if it’s no fun anymore and I can’t do what I want to do, then it’s time to go.

The Mavs had long planned to honor Nowitzki at the last home game of the season. They called it 41.21.1 and hired Lara Beth Seager to make it happen. Five of his heroes—Larry Bird, Scottie Pippen, Charles Barkley, Detlef Schrempf, and Shawn Kemp—made a surprise appearance.

During an emotional speech, Nowitzki announced it was his final home game.

Seager: Well, no one knew that it was going to be his last home game [laughs]. We were celebrating 21 years because obviously no one before has ever been with one team for 21 years. The celebration, the planning of all of that started with Mark, he started working on that in the beginning of the year. Just planning for a celebration for 21 years and then obviously that night had turned into, he decided that it was going to be his last home game.

Cuban: I knew that morning when he had to get shots in his ankles. That’s when he told us.

Nowitzki: Really, the decision to announce it was the one that really fell on me one day or two days ahead. Because I always said I kind of want to make it through the season. But I was relieved the way it went. Just to say it after the last home game and that way, in a month or two, I didn’t have to come back and do a big press conference. That way, it worked out amazingly. I’ll never forget that last week, that last home game with the five idols of mine showing up. The video tribute in San Antonio. I’ll never forget that last week, so I’m really happy how that went and how I closed this chapter of my life.

The Future

What happens next? If Nowitzki had his way, nothing—at least for now. Just a lot of ice cream and Netflix and definitely not working out.

It didn’t turn out like that, although he admits he may have overdone it with the ice cream. His calendar filled up quickly post-retirement, doing work for his foundation and traveling with his family. After we spoke, he left to spend the rest of the summer in Europe with Jessica and the kids. There will be many more trips ahead, many more days with his family. He gave two decades of his life to the Mavericks; he’s giving the rest to them.

But more than likely, at some point and on his terms, he’ll find his way back to basketball.

Nowitzki: Once a year or two go by and we travel a bunch, sure, I can sit down and talk about what my next steps are. Where I could be of value. But, as for now, I just want to get away and enjoy my kids. I just stopped traveling all year long, so I’m not going to just get into something again where I’ll be gone all the time again. This is a time where the kids actually still—you know how it is. The kids now are still enjoying when you’re home.

When they get 10, 12, 13, they don’t care less if you’re actually here or not. They got their iPads and all sorts of things and friends and they go out all the time. But, as of now, they’re still super cute and they want to spend time with us, so I’m enjoying that. I’m going to enjoy that for hopefully a couple years and then, I’m sure, there’s another challenge for me out there somewhere.

But everybody knows I want to stick around basketball. I want to stick around the Mavs, if I can. It’s been basically half my life in the franchise. I’ll always be a Maverick.