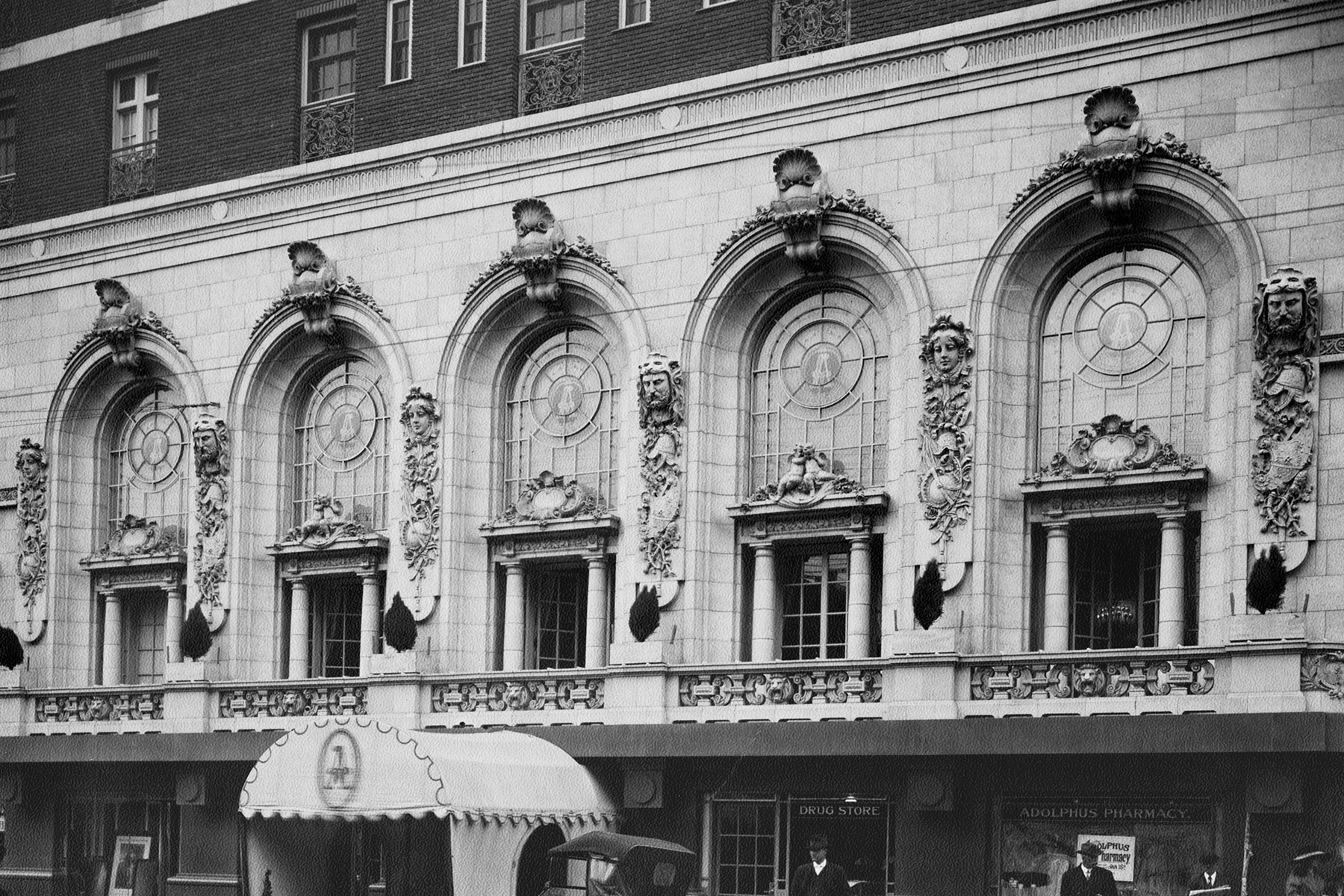

More than a century ago, Adolphus Busch had big plans for Dallas. The co-founder of the Anheuser-Busch empire aimed to grow his Missouri brewing-and-distribution concern. Dallas would be the Texas hub, his first test state in what would one day grow into a national network. History on this next point is murky, but in 1910 Busch was approached by a delegation of prominent Dallas businessmen who prevailed upon him to finance the construction of a first-class hotel for a city on the make. Busch, who already owned The Oriental Hotel, on the southeast corner of Commerce and Akard, loved the idea. He purchased the site where City Hall once stood in the 1880s and spent $1.8 million (about $45 million in today’s dollars) to build a hotel befitting Dallas’ aspirations, aiming for world-class status even then.

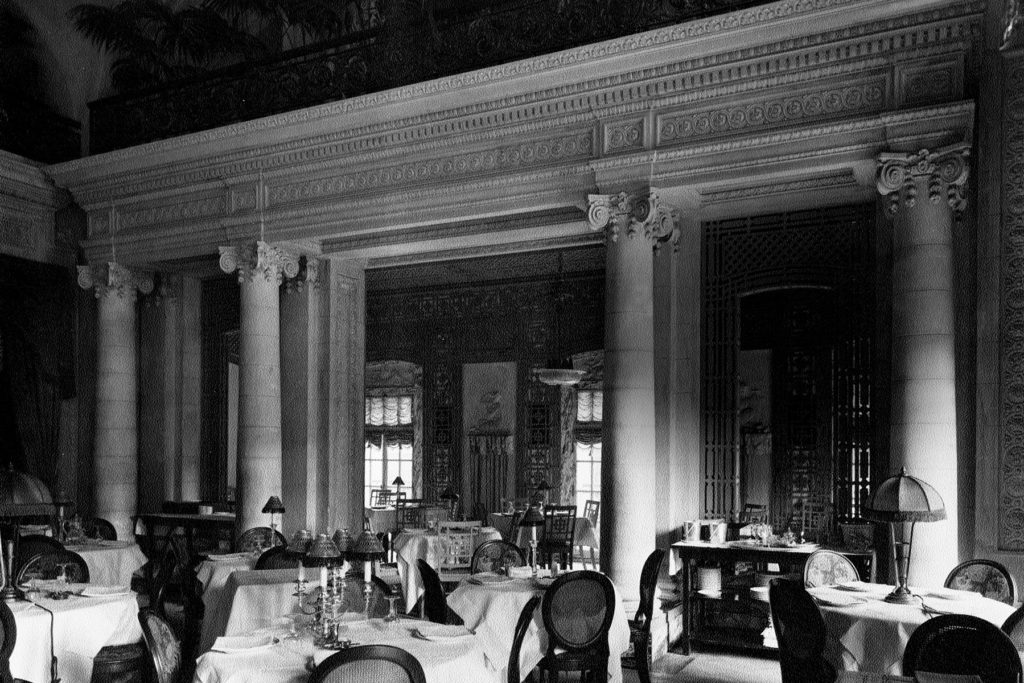

The result, some two years later, was a structure with a quality of architectural ornamentation that was unheard of this side of the Mississippi, much less in Texas: an exemplar of the Parisian Beaux Arts style, with an exterior of tapestry brick, red and gray granite, and gargoyles flanked by the colossal, helmeted heads of Greek gods. The opulent interior was unlike anything Dallas had ever known—vaulted ceilings, sculptured panels in bas-relief, fixtures of brass, ormolu, alabaster decorated with silk and velvet draperies. Busch intended to dub the city’s crown jewel The New Oriental Hotel. Instead, he settled on the Adolphus Hotel.

Busch died the following year, but his hotel became the gathering place for the city’s power brokers and the roost for its most distinguished visitors—from presidents to queens, starlets to boxing champions. Over the years, the hotel was expanded. Ownership changed. As skyscrapers rose and old buildings fell, the Adolphus remained a fixture on the skyline. Its status as meeting place for the city’s movers and shakers, however, had begun to slip. To rectify that, its newest proprietor recently enlisted a small Dallas firm, Swoon, the Studio, to update the outmoded J.R. Ewing aesthetic of excess that had marked the hotel’s public spaces since its last renovation, in 1980. Their goal was to make the Adolphus a hub once more.

“It was that new-money vibe. It was about opulence,” says Samantha Sano, the founder of Swoon. Sano and her principal of design, Joslyn Taylor, envisioned something timeless. “It’s not about gilded and curlicued. It’s about honest, well-made materials.”

They ripped up the floral, wall-to-wall European carpets and discovered the original marble floors underneath. In the French Room, which had been painted with pastel frescoes of cherubim and fair maidens ever since the 1980 remodel, Sano and Taylor have restored the vaulted barrel ceiling to its original wedding-cake white. In the atrium lobby, large palms that had once dimmed and cluttered the Commerce Street-facing room have been replaced by steel factory windows and limestone fireplaces shipped in from France. The object is for the Adolphus to feel as though it again belongs to Dallas, not just its moneyed visitors.

Distinguished Guests

Through the halls of the Adolphus have passed President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Amelia Earhart, Jack Dempsey and Liberace. The mercurial actress Joan Crawford sent ahead an infamous 10-page manifesto to hotel staff that included demands for two bottles of vodka brought daily to her room, a carton of breath mints, extra towels so she could see to the bathroom herself, and no fewer than 20 pillows.

President Harry S. Truman came stamping through the door one wintry day in the late 1940s. He shook the cold from his shoulders and took a look around. “Do you reckon we could get a drink around here?” he said, according to an account in the Dallas Morning News. Truman was shown to the Presidential Suite, where a bottle each of bourbon and Scotch awaited him. “You know, I never drink any Scotch,” the president announced. “Do you think I could trade that Scotch for another bottle of bourbon?”

A Piano Destined for the RMS Titanic

It’s impossible to miss the enormous Steinway piano sitting in the middle of the French Room Salon. For decades, the tickling of those ivories has meant tea time. But they very nearly plunged to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean in 1912. As the story goes, the Steinway & Sons concert grand was set to board the RMS Titanic, along with its millionaire owner, Benjamin Guggenheim. Due to a delivery snafu, the piano failed to arrive before the ship embarked on its maiden voyage. Four days later, the Titanic struck an iceberg. For reasons that remain unclear to this day, rather than board the lifeboats, Guggenheim slipped into his finest suit, tucked a rose in his buttonhole, and drank brandy as the ship capsized. Busch later purchased the Steinway for his new hotel.

Dorothy Franey’s Ice Revue

Nowadays, the French Room is better known as a quiet place where tea is served in fine china. But there was once a wilder time, when the room was filled with big bands, bootlegged whiskey, and an ice rink. It was usually covered by a retractable floor, but on special nights Dot Franey, a retired speedskater and Olympic gold medalist, would glide across the ice with the grace of a dancer. In the early ’40s, she brought her Broadway-on-ice show to Dallas for a month. Franey ended up staying at the Adolphus for 14 years, where she directed, produced, and choreographed her own shows in what was then known as the Century Room. For one production, Franey attempted to re-create Singin’ in the Rain on ice. While skaters in yellow taffeta raincoats swirled around the rink, she had the hotel engineer kick on the sprinklers. The spouts got stuck, and the audience was soon flooded out.

Chandeliers Fit for a Horse Barn

In 1980, when the last remodel of the Adolphus Hotel began, just about everything that wasn’t nailed down—and some things that were—was put up for sale. Silverware, brass sconces, Chippendale chairs, even sinks—if the item had a price tag, it was fair game. One of the few fixtures that remained off-limits to scavengers, however, was the chandelier that now hangs above the escalators. Adolphus Busch himself had commissioned the chandelier and an identical twin for the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in 1904, colloquially known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. There, the radiophone awed spectators. The debut of the X-ray machine gave the public a glimpse at the future of medicine. And hanging above the Anheuser-Busch exhibit were the two bronze chandeliers, ornamented with hop berries and leaves, along with his brand’s signature eagle with wings spread wide. At the end of the exhibition, both chandeliers were moved to the stables where Busch kept his prized Clydesdale horses, and one of them eventually wound up in the Adolphus.

In 1980, when the last remodel of the Adolphus Hotel began, just about everything that wasn’t nailed down—and some things that were—was put up for sale. Silverware, brass sconces, Chippendale chairs, even sinks—if the item had a price tag, it was fair game. One of the few fixtures that remained off-limits to scavengers, however, was the chandelier that now hangs above the escalators. Adolphus Busch himself had commissioned the chandelier and an identical twin for the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in 1904, colloquially known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. There, the radiophone awed spectators. The debut of the X-ray machine gave the public a glimpse at the future of medicine. And hanging above the Anheuser-Busch exhibit were the two bronze chandeliers, ornamented with hop berries and leaves, along with his brand’s signature eagle with wings spread wide. At the end of the exhibition, both chandeliers were moved to the stables where Busch kept his prized Clydesdale horses, and one of them eventually wound up in the Adolphus.

Lady Bird and the Highland Park Horde

In 1960, then Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, arrived in Dallas in the heat of a bruising presidential campaign. The moment they stepped out in front of the Baker Hotel, they were beset by a howling mob, mostly society women from Highland Park and North Dallas, who had accompanied Republican Congressman Bruce Alger to give the Johnsons a chilly reception. Johnson’s canny eye for optics spotted opportunity. Scheduled to make an appearance at the Adolphus, he and Lady Bird strode across Commerce Street and into the maw of a hostile crowd amid cries of “Judas!” and “Socialist!” Inside the lobby, Johnson’s gamble paid off. A television camera caught him escorting a composed Lady Bird through the jeering crowd. The spectacle didn’t sit well with Texans, and Kennedy pulled off an upset win. Without the ugly scene at the Adolphus, Nixon likely would have carried the state.