On a summer Saturday last year at DFW Airport, in the early evening, Sean Donohue wanted his shoes shined. Understandable. As the CEO of the airport, Donohue runs an $800 million operation with 1,800 employees. He’s a big shot. Problem was, the shoeshine man whom Donohue approached in Terminal D was knocking off for the day. It was after 6 pm, when the shoeshine man normally caught his bus home, as airports on Saturday evenings aren’t swarmed with well-heeled customers. According to the man’s employer, Goodfellows Shoeshine, he apologized to Donohue for bad timing and left.

Goodfellows president and CEO Shelley Bonner-Carson got a call later that evening from an airport executive who lit into her for 45 minutes. Two days later, she claims, she was “berated, insulted, and disciplined” in an hour-long conference call with two airport execs who suggested that Goodfellows could lose some of its prime terminal space—which is exactly what happened the following week.

Soon after, on an August 1 phone call, Bonner-Carson asked the same DFW executive, “What part of the lease agreement am I in breach of?” The exec said, “Hold on.” Bonner-Carson could hear him turning pages. Minutes later, he replied, “Hours of operation.” Given that there were no set hours the shoeshine stands were to be open, she knew that it was an easy accusation to levy and a hard one to disprove.

Lawyers got involved. In April, after months of charges and countercharges, Goodfellows’ lease was terminated by the DFW Airport board. “Those son of a bitches pulled the rug out from under me,” Bonner-Carson says.

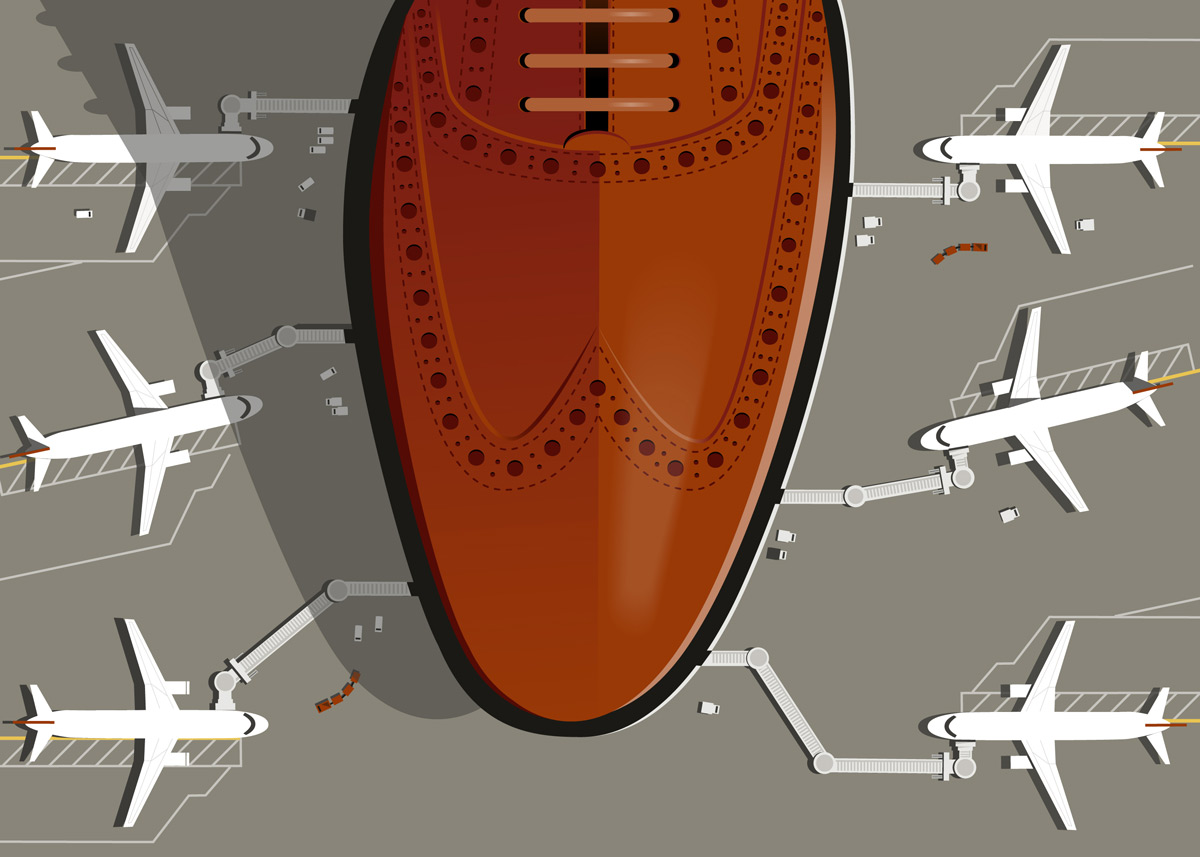

All because the CEO couldn’t get his shoes shined on a Saturday after 6.

The term you hear over and over is “play ball.” Anyone who complains knows the risk.

In letters between counsel for the airport and Goodfellows, airport officials reject the notion that Goodfellows was targeted, saying that the company’s lease was terminated “due to the continued and pervasive failure to keep all concession locations open and staffed for business during required business hours.” Which might be true. It’s entirely possible that an otherwise successful and respected small business decided to ignore entreaties from DFW Airport so it could be found in breach of contract and lose its profitable spots in one of the country’s busiest airports. It’s also possible, I suppose, that a culture of “crony capitalism” (the words of D Magazine’s publisher, in 2010) will once again show itself should Bonner-Carson follow through on her threats to sue.

Before Goodfellows won the shoeshine contract, in 2012, DFW Airport had a slapdash arrangement with its shoeshiners. Spaces in the airport were provided to independent contractors, and, according to Ronquillo, little to no records were kept as to how much money they made or how much they paid the airport in fees to rent the spaces. The quality of shines was known to vary widely, to say the least.

That changed with Goodfellows. The company spent $500,000 on equipment and space improvements, opening shoeshine stands and two retail stores that offered not only shines but shoeshine product, too. The 10 locations earned about $1 million a year, of which the airport received 10 percent plus other maintenance fees. That might not sound like much, but in 2012 the average full-time shoeshine person made just over $20,000 a year, according to government figures. Each concession throwing off nearly five times that amount was, Bonner-Carson says, an eye-opener. “Other concessionaires warned me they’d come after me and want a bigger cut,” she says. “I showed them how lucrative it could be.”

Goodfellows had a good reputation nationwide at the seven other airports where it operated, and at DFW Airport. Its locations listed on Yelp, at DFW Airport and at San Francisco’s airport, rate 4.5 stars. It won a DFW “champions of diversity” award in 2013 and rated 100 percent positive in passenger surveys six times in 2012 and 2013. Bonner-Carson says customer service has been important to her since she started the company in 1991, when, needing her boots shined before an important meeting at a casino hotel in Las Vegas, she realized all the shoeshiners were located in men’s bathrooms.

After the early kudos in Dallas, Goodfellows began getting citations from the airport. In correspondence with Goodfellows attorneys, DFW Airport claimed there were numerous complaints filed by staff (rarely by traveling customers) concerning unstaffed shoeshine stations. Goodfellows says that when it investigated the complaints, it often found that shoeshiners were being written up when they took bathroom breaks. The airport told the company it had to stay until the last flight in a terminal left, even though the airport later acknowledged it couldn’t provide flight schedules by terminal, and even though a survey of other airports showed that most shoeshine stands close in late afternoon or early evening because of decreased foot traffic. Other alleged harassment by DFW Airport—writing up the company for water damage in its ceiling; Goodfellows uses no water—escalated.

But why would an $800 million operation like DFW Airport care about a tiny shoeshine business that generated just a million bucks? That’s where the culture comes into play. The executives want a level of control over businesses that operate there. That’s why even companies that are owned by minorities—or, in this case, a woman whose employees are 95 percent minority—are encouraged to have “minority partners.” What’s a minority partner? For years, most of the stores you see at DFW Airport (and Love Field) have or have had a local minority “partner” who contributes nothing to running the franchise except his name. This was done under the guise of encouraging minority business development—especially funny when the minority owner was forced to add a minority partner for what I guess is some sort of double minority business development.

The term you hear over and over is “play ball.” In other words, that the entire concessionaire system at DFW Airport—and it’s been said just as often about Love Field—is one where the squeeze is put on so that the terms are always favorable to the airport, and anyone who complains or out-performs knows that their business is at risk.

Robert Crews ran a DFW Airport bookstore and sued the airport in the 1990s for trying to force him into just such an arrangement. He said at the time, “Being a subtenant is like sharecropping. You make just enough to cover the seed and have food to eat, but you never get out of debt.”

Ronquillo puts it a bit differently. “Based on my past and current representation of concessionaires with disputes against DFW Airport, there still remains today a culture of ‘ethnocentric entitlement policies’ that penalizes independent successful entrepreneurs with proven track records who are not part of the inner circle,” he says. “We need to change that culture.”

All this could be nothing but lawyer posturing. The airport might have ousted Goodfellows because it was tired of fielding complaints from passengers. The Goodfellows story might have nothing to do with history or culture or money or inner circles or a CEO’s shineless shoes. Maybe DFW Airport is poised to astound us all and provide shoeshiners in every terminal who work far into the night, up until the last plane takes off, even if flights are delayed. I’m anxious to see. So, too, is Bonner-Carson.