Rene Guzman and Leonardo Lopez lived in West Dallas and supported their drug habits with burglary. Someone in Ellis County had seen them in action and written down the plate number on Guzman’s car. That’s what brought the sheriff’s deputies to their door at 2810 Ingersoll Street on February 15, 1971, the day after Valentine’s.

Deputies Wendell Dover and A.J. Robertson had driven up from Ellis with the arrest warrant. They enlisted the help of Samuel Infante, a Spanish-speaking deputy from Dallas. When they reached the house, Guzman and Lopez were outside working on a car. They let the deputies in, and Guzman said they could use his phone to call for some consent-to-search forms. Everyone relaxed at first. But then Guzman and Lopez pulled guns on the deputies, and the bloody night was set in motion.

It wasn’t long before two Dallas deputies, William Reese and A.D. McCurley, knocked on the door with the forms. A voice inside told them to come in. The first thing they saw when they opened the door was three deputies tied up in chairs. The second thing was Guzman and Lopez pointing guns at them.

The five deputies, all with their hands bound, were led out to the Ellis County squad car. Deputy Infante’s hands were untied, and he was told to drive. The two gunmen sat beside him in the front seat, one pointing his pistol at the four in back, while the other jammed his gun into Infante’s side.

“I think they’re going to kill us,” Samuel Infante told his fellow deputies. William Reese tried to plead with them, but their abductors knew the cops could identify them.

“I think they’re going to kill us,” Infante told his fellow deputies.

Reese tried to plead with them, but their abductors knew the cops could identify them now. They ordered their captives out of the car.

Reese made his move. He took a swing at Guzman and missed. Guzman shot him. Infante barreled into Lopez and was shot and killed, but that gave McCurley enough time to throw himself over an embankment. He rolled toward the river, stopping just short of the water’s edge, where he lay listening to the shooting from above. He eventually managed to cut his ties on a tree, and then he got back on his feet and ran.

McCurley made his way to a gas station and called headquarters. Then he borrowed a derringer from the attendant and headed back to the scene with Dallas police. In the darkness, he could see that the squad car and the gunmen were gone. Reese and Robertson’s bodies were on the ground. Infante’s body had been left on a pile of garbage. A gravely wounded Dover was found in a nearby field and taken to Parkland Hospital.

The manhunt that ensued was one of the biggest in Dallas County history. From an informant, it was learned that the fugitives were hiding in a boarding house off Ross Avenue, in East Dallas. The neighborhood was barricaded and 60 cops went in. At first they attacked the wrong apartment, and two occupants inside were wounded by gunfire. But in the end, they got Guzman and Lopez.

In 1991, Lopez, to everyone’s surprise, was deemed rehabilitated and paroled after serving only 16 years. His new life as a free man was short-lived, however, and he returned to prison, where he and Guzman both remain to this day.

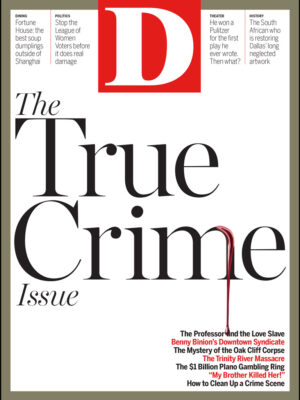

Forty-five years after it took place, the Trinity River Massacre, as it was called at the time, is remembered by only a few. Of the seven in the car that night, only the killers are still alive. Wendell Dover recovered from his wounds and became a police detective in Ennis, then a mail carrier in a nearby town. He died in 2005. I couldn’t find anyone in the Ellis County Sheriff’s Office who remembers Dover, A.J. Robertson, or the massacre. But Dover’s friends remember. Bobby Joe Curry says he was a quiet man who liked to spend time with his buddies. About the only time Dover talked about the massacre was when Lopez got paroled. He was irate.

A.D. McCurley stayed with the Dallas County Sheriff’s Department, becoming captain in its criminal division. He died in 2001. He is mainly remembered for being a first responder inside the Texas School Book Depository following the JFK assassination. The Dallas County Sheriff’s Association tries to keep alive the memory of their fallen deputies. Each year, new deputies receive commendations named for Samuel Infante and William Reese. But memory inevitably fades as retired lawmen grow older and depart.