The writer Kathryn Marshall McClendon shot herself in the head on December 18, 2014, at her home in west Fort Worth, at age 63.

About 60 mourners attended her memorial service, including her brother, Rob, a prominent Fort Worth civil engineer, and her younger sister, Caroline, a New York visual artist with whom Kathryn’s life and writing career were deeply intertwined. Of the many writers who had been drawn into her fierce barnstorming of literature, sexism, and mortality, only a few made it to the chapel at the Greenwood Funeral Home. Jan Reid, Dick Reavis, Roy Hamric, and I sent a floral arrangement. Dick, who lives in Dallas, was able to go, but Roy was in Thailand. Jan, himself shot during a 1998 hold-up in Mexico City, recounted in The Bullet Meant for Me, was unable to come for medical reasons. I could have driven up from College Station in the pelting rain, but I chose to be somewhere else. It has taken a while for me to understand why. To touch the bullet meant for her.

I met Katy, as we all called her, in the mid-’70s, at the Texas Observer, whose offices were in an old wooden house on West 7th Street in Austin that was owned by attorney Dave Richards, husband of Ann. Jim Hightower was editor. His brilliant and wildly overqualified Ivy League managing editor, Lawrence Walsh, was soon to become Katy’s second husband. The first came via an improbable marriage involving Hare Krishnas. There would be two more—to Bob Dattila, agent to writers such as Jim Harrison and Thomas McGuane; and finally to the late Paul McClendon, a former SMU sweetheart and later a Fort Worth businessman. In her final years, Katy was involved with Darrell Gladden, a roofing tile contractor with a quick wit and a lot of patience, and Tom Coan, a physics professor at SMU. Shortly before her death, she began seeing a medical examiner she’d met at a drugstore in Fort Worth. Although she often talked about the importance of solitude as a writer, in truth Katy needed to be around people. It was for her violent farewell that she chose to be alone, and definitive.

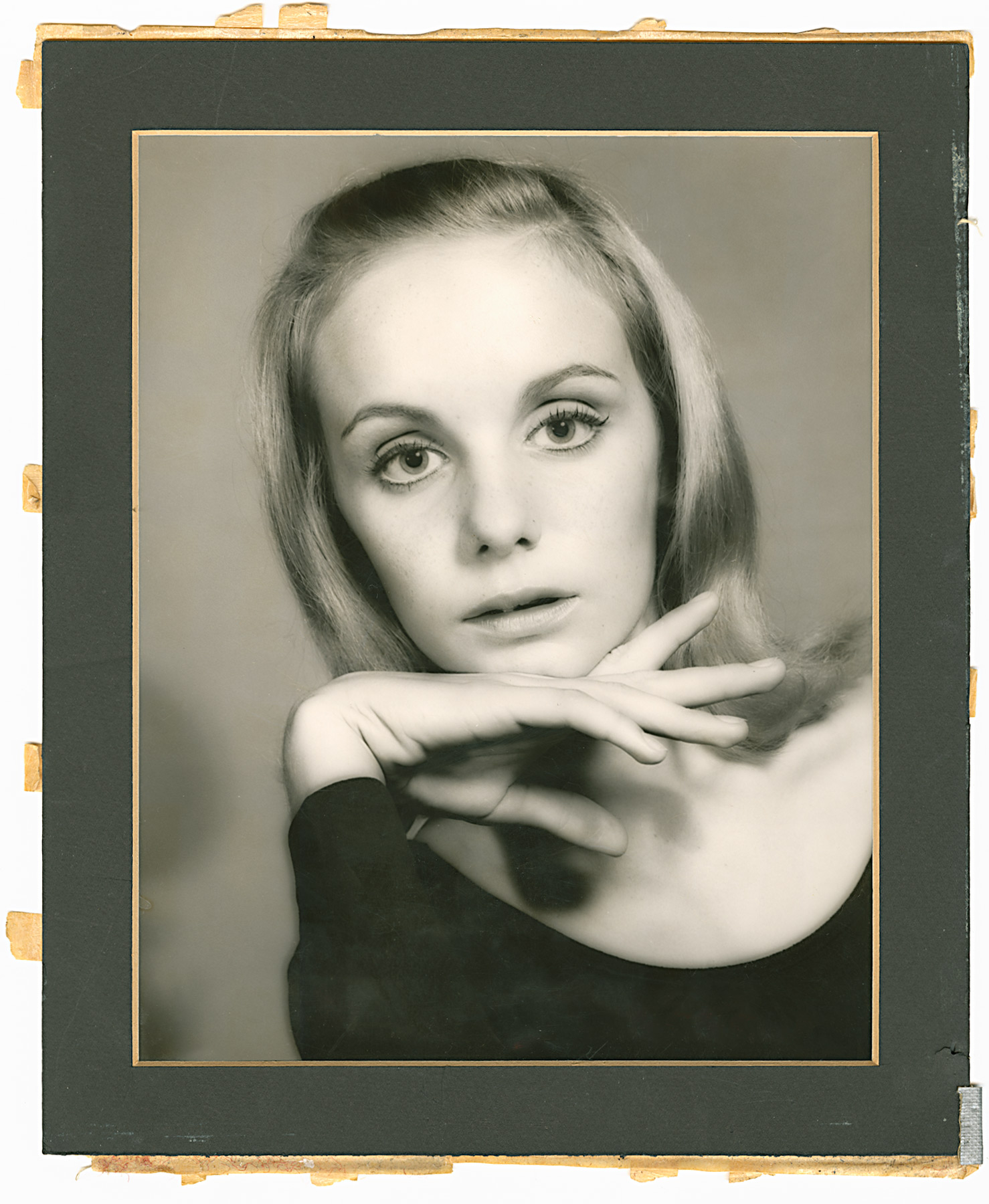

During her early 20s, Katy was infectiously cute, a petite blonde who wore her hair in the stylish bob she favored all her life. Her liquid hazel eyes and penetrating gaze radiated sensuality, backed up by restless energy and a smart mouth made for Dorothy Parker.

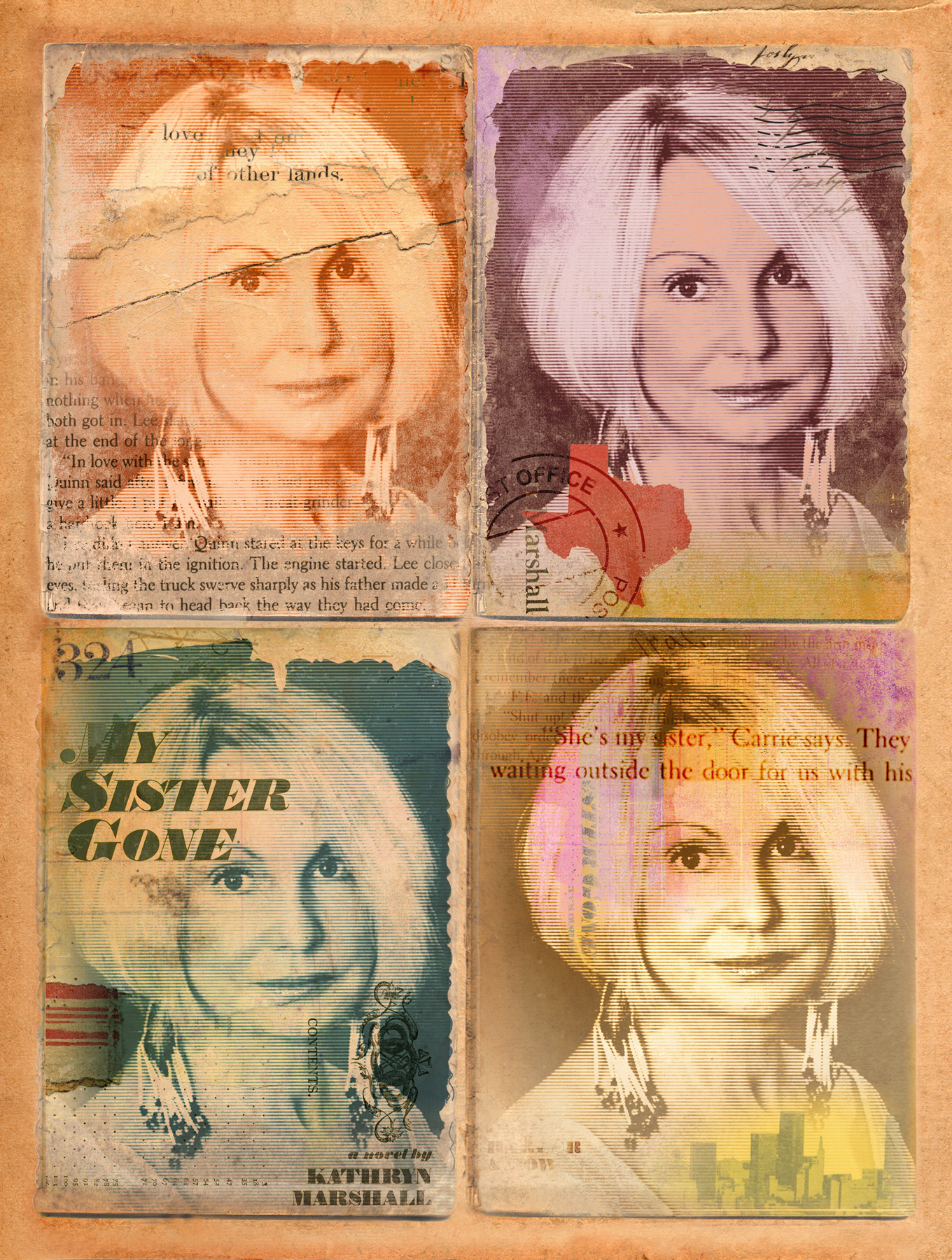

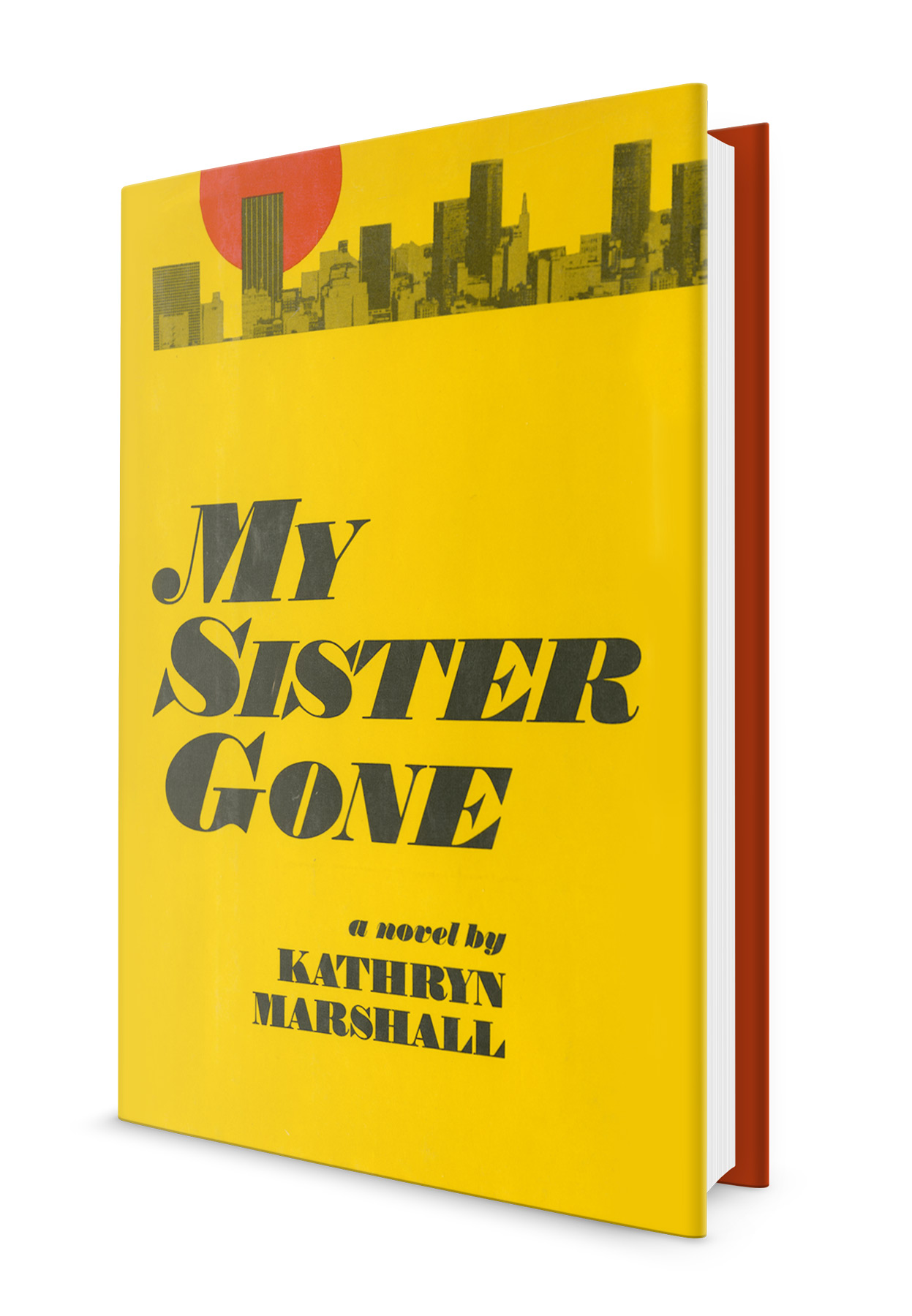

Katy knew people at the magazine and took the review personally. After that, she turned to magazine articles, literary essays, and short stories, notably the wicked and minimalist “In Case You’re Wondering How Come I’m Sitting Here in the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport,” included in the anthology Her Work: Stories by Texas Women (1982). She also produced a well-regarded and still compelling nonfiction book, In the Combat Zone: An Oral History of American Women in Vietnam, 1966-1975 (1987). It was hailed as a crucial record of women’s history in the war. But she never published another novel. She started several and dropped them. A final attempt was in progress when she killed herself. She described it to Jan as a “hideously Gothic tall tale.” Rob has the manuscript and says it appears to continue the story of My Sister Gone. It may or may not ever be published.

The day I met Katy at the Observer office, I did my best to impress her with my keen hipness to the New York literary scene. Which was zilch. “I guess you’ve been to Elaine’s?” I ventured. She cut one of those looks that a woman in a bar would give you if she wanted to shrivel your balls. “Elaine’s? Where’s that?” Then she walked over my corpse and out of the room. I was enchanted for life. And now she is dead. The only public notice was an obituary in the Star-Telegram, written by her sister Caroline.

•••

The passage was intended to account for why, as her writing career waned and a new and far more difficult life unfolded, she had become so interested in the stories of women serving in Vietnam that she would seek them out across the country, write to them, call them, and meet them in remote places. She sought them in part because their transitory lives, their alienations, their wounds, their struggles within a war largely conceived and carried out by men, so mirrored her own. “As a kid in the suburbs of north central Texas during the ’50s and on through the ’60s, I was essentially isolated from anyone who wasn’t white and upper-middle-class,” she added. Breaking that isolation, confronting it with all her strength and spirit, was her true life’s work.

“Katy was a true individual and seemed to be punished for that bravery by people who need others to bow down to their control,” says Dana Joseph, her friend and editor at American Way magazine during its golden age of the late ’80s and early ’90s. “I don’t think Katy was the back-down type. As petite as she was, she had a pretty formidable physical presence: all muscle and sinew in that compact ballet body and that quiet I-dare-you-to-mess-with-me attitude that I’m sure she wouldn’t have hesitated to back up if she’d need to. She was a rebel and might have survived better if she’d been born a man. People can’t generally handle that kind of moxie in a woman.”

The merger of Katy’s identities as a woman and a writer evolved all her life, becoming the dominant if merciless call of her existence.

At age 16, she left her family home for good. She had been born in Memphis, Tennessee, because her mother, Ruth Taylor Marshall, had been visiting her own family near the Delta town of Osceola, Arkansas, and Memphis was the closest city with a good hospital. The Taylor family owned a rice plantation, but Ruth had been lured away by Bill Marshall, a WWII vet who had gone through hell at Bastogne but had a promising career ahead with a Ph.D. in logic. The family moved shortly thereafter to Texas, and Katy grew up in Arlington, Austin, and Irving. Bill joined the faculty at UT Arlington as a professor of mathematics. He cut a brilliant and colorful figure, but he was an alcoholic who could turn boorish and aggressive when drunk. “He brought self-destruction to the level of a sacrament and deeply infected Katy,” a person close to the family says. Ruth was a traditional Southern lady who put up with it. Friends and family say that Katy was like her father; Caroline like her mother. It is revealing that Katy had a poor relationship with Bill; a good one with Ruth. Both parents have passed.

Katy’s exit as a teenager came courtesy of her ballet skills, which were honed enough to gain her a spot with the Dallas Civic Ballet, followed by a Ford Foundation Fellowship for the New York City Ballet Company’s School of American Ballet. After several unchaperoned months in Manhattan, she returned to Texas. She said she hated the hyper-competitiveness. She found a place in Dallas and lived on her own while she finished a high school degree in Arlington.

In 1969, she enrolled as a drama major at SMU. That didn’t take, either, and after a year she left. Her parents divorced—later remarried and divorced again. That summer, after shopping at a yard sale in East Dallas, Katy was accosted and raped. As was more common at that time, she said little about it.

She drifted, found drugs, fell in with the Hare Krishnas. She used her dancing skills at DFW Airport to get donations. At some point she was married in a Hare Krishna ceremony by some kind of minister temporarily a guest at the Dallas County jail. The marriage failed quickly, and she made her way to Austin, where she took her B.A. in philosophy at UT in 1973 and began a long relationship with the late UT philosophy professor Bob Solomon. After graduation, she moved west for an M.A. in English at UC Irvine. She began her first novel and lived with a Vietnam vet with PTSD who influenced her later decision to write In the Combat Zone. Connections at UC Irvine led to the iconic editor Cass Canfield at Harper & Row. The older Canfield took a shine to the bright girl from the South and published My Sister Gone. Later, he allowed her to live in his home (“in a closet,” she later said) while she worked on Desert Places, which he also published.

In 1976, she became the first female writer (and the second woman—the first was visual artist Ann Matlock) to receive a prestigious Dobie Paisano Fellowship, offered by UT and the Texas Institute of Letters. She asked Jan, the co-recipient for that year, to allow her to take the first residency at the 254-acre spread near Austin, rather than the last, because she was afraid her boyfriend, the Vietnam vet, would kill her. After the ranch, she taught writing at UT and revived her relationship with professor Solomon, although it eventually ended.

Katy’s marriage to Lawrence Walsh, the Observer’s managing editor, seemed to provide much-needed stability to her personal life and to mark her ascension as a Texas writer, sometimes landing her name alongside those of other acclaimed female Texas authors of the period, such as Beverly Lowry (like Katy, also born in Memphis) and Shelby Hearon, whose Armadillo in the Grass, published in 1968, was part of the favored canon among Austin literati.

Lawrence got a Nieman fellowship and they moved to Boston. Katy taught in short bursts at several universities, including Penn and Harvard, and wrote a few stories and essays. In 1981, the marriage ended by mutual agreement. Lawrence later married the beautiful, fast-rising journalist Mary Williams, now Mary Williams Walsh, a star at the New York Times. Lawrence, Mary, and Katy met for breakfast once in 1987, an experience he described as “way past strange.”

Katy found more university gigs, finally one at Mount Holyoke, ending in 1985. She loved working there and was “heartbroken” that her contract was not renewed after three years. “She felt it was just too hard to earn a living as a writer,” her sister Caroline says. She would continue at the gypsy typing trade a little longer in different ways. The results didn’t change. To paraphrase Willie, the writing life weren’t no good life. But it was her life.

•••

Being a writer in Texas is an ordeal for all. I had approached the issue in an essay in the Dallas Times Herald in 1981, shortly before Katy’s Texas Observer piece. I mailed a copy of the essay to Katy, then in New Hampshire. I knew her thoughts about the struggles faced by women writing in Texas were similar to those described by Hearon and so many others. The iconic Katherine Anne Porter said she “had to leave Texas because I didn’t want to be regarded as a freak. That’s what they all thought about women who wanted to write.”

I included with the copy of my article a hand-written note to Katy explaining that I didn’t address the problems of Texas women writers per se in my essay because I was focusing on the problems all Texas writers had in finding an identity not imposed by the Eastern literary establishment.

Her Observer statement became, in part, a reply to my note. While she addressed the same Texas writer identity crisis about which I had written, and took special aim at Larry McMurtry, there was a surprise swipe at me. She inferred that “by ‘Texas writers’ Rod means ‘Texas men writers.’ … Now I think Rod is right in noting that those of us who don’t belong to the [Eastern] fraternity must write ourselves out from under two qualifiers, and I think he’s right, for now, in segregating the ranks. Because, as I’ve lately come to see, ‘woman writer’ and not ‘Texas writer’ is our primary state of emergency.”

I agreed with Katy, except for the use of the note, but she later told me that Ronnie Dugger, publisher of the Observer, had put her up to it. Dugger (who was once married to Katy’s stepmother, Jean) had just purged the Observer of writer Dick Reavis for having been a communist and me, as Observer editor, for not firing him. It was the last time leftist radicals ran a major Texas publication. Hard feelings had not yet subsided. Still, the incident served to bolster my friendship with Katy by honing our sense of awareness of the impact of what we write. The Buddhists say that your teacher will come when you are ready. I like to think we were both ready.

An insightful 1977 interview with Jo Ann Bardin in the now-defunct UT student publication On Campus shows Katy already testing and developing her thoughts on the experiences of women writers and on the very formulation of language itself:

“I’m interested in women and sexual paradigms, particular sorts of women and the sexual models that they find themselves working from in their lives. Also, I’m interested with how that ties in with women as artists, more particularly ones who want to write in this time.

“I think there’s a lot of junk being written by women today because there are a lot of angry and indignant women. They ought to learn that if they’re going to write good literature, they have to make their anger serve an end other than political ends. And a lot of that has to do with being conscious of language and the medium they’re working in. …

“It is because women have been taught to be less sure about their utterances, less opinionated and less rigid in the way they think about themselves and the things they say, that their speech patterns and rhythms are much more open, flexible, and fluid than those of men. There’s a lack of self-confidence in the way some women speak and write—that’s the negative side of it. On the other hand, there is an openendedness to this so that when the language is bent properly, it makes for a lucid writing. There is a possibility for real poetry in women’s writing, I think.”

Probably the most symbolic expression of Katy’s awareness of herself as a writer who is a woman was not a written one at all, but instead something she did at the Paisano ranch house, during her 1976 residency. She had come back to Texas from California for the fellowship, and the primitive, isolated setting at the Hill Country ranch freaked her out—as it did other writers from time to time. “It was fall, and the creeks rose and the lower water bridge got covered, and all the rattlesnakes came to nest on the front porch,” she said in a 2005 interview in Dallas with Dr. Audrey Slate, who managed the Dobie Paisano program for 30 years and is writing a book about the recipients. “I was scared of rattlesnakes, and some bikers came through the property and my daddy brought me a rifle so I could shoot the bikers or whatever. So I was pretty scared at first but … I relaxed into it eventually.”

Unlike the men who preceded her, Katy also saw it as a male space. Especially when looking at the scribblings and drawings on one wall of the room she used for a study. They had been left by the likes of A.C. Greene, Bud Shrake, Gary Cartwright, and Jim Franklin. Her sister Caroline, who came to visit at the ranch to help with the loneliness, says Katy just thought the wall was ugly and wanted to make the house brighter. So she painted over it.

But there was more to it than that. Katy told me the real deal, and she said the same to Dr. Slate:

“I got there, and as you know I was the first woman writer,” she told Slate. “I was young, I didn’t know, I mean I sort of knew some of these older guys, who were famous Texas writers. And they, I don’t know, they just seemed very male and a lot older, and I walked into Dobie’s study and put my typewriter on his desk and looked up at this wall that to me just looked like a bunch of graffiti. A bunch of old drunk men that didn’t like women, and I just said, ‘Well, I’m not going to sit here for six months and look at this stuff.’ I went out and bought a bucket of yellow paint and painted over it and never thought I was defacing history. Texana history. I just didn’t want to look at it. It was ugly, and I kind of got pretty upset about it.”

For some years, Katy’s redecorating was considered by some of the Old Guard, especially Greene, as a sacrilege inflicted by a “goddam woman from California.” Since then, the wall has been painted over several times and the entire house renovated by its owner, the University of Texas. The painting drama is barely known by newer writers or snarled at by the old school. But no one writes on the walls anymore.

“Back then, one was trying to be a writer first and a female second but was often treated as female first and writer second,” recalls Hearon, who now lives in Vermont. “I do remember Katy being with guys but not them talking about her writing. And of course those of us who were wives and mothers had to struggle uphill to get writing time. It was hard to be taken seriously as a writer if you were a woman in those days.”

As surely as the ’70s put Katy in the spotlight, the ’80s and ’90s pushed her along a path of hard living and excess. Somewhere in that time the cracks that had opened in her earliest years widened into the abyss that she faced with her finger on a trigger. George Fortenberry—a WWII Southwest Pacific Theatre vet and prominent UT Arlington English professor who married Katy’s mother, Ruth, after her second divorce from Bill—was as close to Katy as anyone in her life. He is now in his 90s. “The truth is, we lost Katy a long time ago,” he said after learning of her death.

“Katy absolutely adored Dad and never stopped telling me how much she missed him and how he was in many ways her best friend,” said Martha Odya, George’s daughter. “It led to a closer friendship between us. Whenever she called me, she would say, ‘Martha, it’s your evil stepsister calling,’ in her most wicked voice. Then we’d both laugh and start exchanging outrageous stories and laugh some more. I’ll miss her terribly.”

By the mid-’80s, still jumping from university to university, Katy had met and would later marry Bob Dattila, and moved into a high-octane life in Livingston, Montana, and West Hollywood, trying to keep up with the macho writer world of her husband’s famous clients. The drinking and drugs were harder on her than on the men, in part because she was physically smaller, in part because there was too much of it, period.

But she did find her footing enough to complete In the Combat Zone, and although they divorced in the early ’90s, Katy would always think of Bob as her great love. Even though, after the divorce, she called me one day, obviously drinking, to tell me with great excitement how she had driven up into the Montana mountains with the photo albums of their wedding and marriage and “shot the shit out of them.” A few years before she died, Bob visited her in Fort Worth, but it didn’t work out. In a note to Roy Hamric at about that same time, Katy said Bob “was, and always will be, the love of my life … And if I could turn back time (HA HA), I would go back to all those stupid, silly, Alice-in-Wonderland things we used to say to one another, and laugh all the time, and I would act stupid all the time and do animal imitations all the time with Bob.”

I had reconnected with Katy in the late ’80s, when I was the editor of American Way magazine. I assigned her the first of what would be a long-running series about writers and their places, starting with Faulkner’s Oxford. She did a good job and clearly loved the chances it gave her to travel on someone else’s dime. For several years, she was a steady contributor.

“Back then, one was trying to be a writer first and a female second but was often treated as female first and writer second.”

“The last time I saw Katy Marshall she was being escorted out of Southern Progress with a guard who had spent the afternoon watching her pack all of her personal items,” says former Cooking Light fitness editor Melissa Chessher, now a professor at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. “She was fired and banned from the building. A week or two before her firing, she had ordered all this lingerie for a story she wrote about the power of frilly, sexy things, and as we talked in her office (and with the door open), she proceeded to try everything on … I loved her intensity, intelligence, focused clarity, her fearlessness, her commitment to the sisterhood, and her adoration of men. She never changed her hairstyle—suggesting to me she always felt comfortable with who she was and who she wanted to project—preferred jeans, and always seemed comfortable regardless of the company.”

Birmingham also allowed Katy to spend more time with her equally beautiful sister Caroline. They were quite a pair—not lost on the local male gentry. At one point Katy may have sort of married a wealthy man and as quickly obtained an annulment. But the relationship between the sisters was and always would be dogged by as much hate as love. Any reading of My Sister Gone and the “In Case You’re Wondering … ” story reveal that emotional yo-yo. It wasn’t mere sibling rivalry. Katy’s writings, which were always about family and relationships, hewed toward violence and emotional agony. The feral older sibling (aka Katy) in My Sister Gone not only kills her grandfather but almost kills her younger, cautious sister (aka Caroline) and eventually dies in a Dallas tenement from a botched abortion and her own self-loathing.

“In Case You’re Wondering … ” is a steadily darkening monologue from an unhinged fashion model (Katy) featured in a current issue of Big D magazine who goes to DFW Airport for drinks even when she’s not flying. She is telling a perfect stranger at the bar about how her artist sister Loreli (Caroline) invited her to Thanksgiving dinner and then stole the boyfriend she had met at a McDonald’s in Oak Lawn. It all wound up with ax-wielding violence that the model summarizes as: “Loreli? They took her to Parkland.”

In real life, the sisters were so close and grew up in a family with such issues of alcoholism and dysfunction that it seemed only natural they would also at times hate each other. But the photo that Katy kept on her desk in Fort Worth to the end shows the two of them in 1977 cuddling together as only sisters filled with love could. When I called Caroline to talk about Katy’s passing, the first thing she said was “I miss my sister.” The pain in her voice was unmistakable.

•••

By the late ’90s, Katy had decided to leave writing completely. She told me she thought she wanted to become a nurse, and that’s what she did. It sounded like a strange plan, but in fact, all of her life, Katy had shown a strong interest in helping other people, according to Caroline. “She said she was tired of being around people in an industry just thinking about themselves all the time. She wanted to give back,” Caroline says.

By 2001, Katy got her nursing degree from Baylor in Dallas. It was a short career. She worked a few days in the Parkland ER, didn’t like it, and eventually lost her license because of excessive DUIs. But she used her skills to help manage the Agape Clinic in East Dallas, a free healthcare provider with mostly Hispanic clients. Katy was fluent in Spanish, had a gift for fundraising, and enjoyed the job. But eventually she left that one, too.

Meanwhile, she had married Paul McClendon, the Fort Worth businessman, and was able to relax financially. She continued to do volunteer work at a clinic in Fort Worth and moved into the museum scene. Outwardly, she might have seemed an artsy socialite. Inside, not at all. Most of the marriage, she and Paul were estranged and lived in separate houses. She filled hers with artwork and fine furnishings, and indulged her love of Zuni jewelry. She showered her friends with gifts.

Katy was not getting better. She visited Roy, a former UT Arlington journalism professor who by then was editor of the great but short-lived Desert-Mountain Times in Alpine. He remembers one of her visits well. “She was desperate, and I had a terrible intimation when we dropped her off alone at her motel one night,” he says. “When she called the next morning, I was greatly relieved.”

Paul died in 2009, having slipped back into his own addictions, and Katy later began seeing Darrell, the roofing contractor. The relationship lasted several years. He was good for her. They traveled some and loved to go to Austin and stay at the Hotel San José, a hip boutique just south of the river. Katy fit right into the theatrical and wanton ways that made the hotel famous, demonstrating her disdain for clothing by walking around naked in the hotel’s prized corner guest room of glass windows, and on one occasion searching half-clothed for her cat, which was back home in Fort Worth. Then there was the night Katy took the sudden notion to walk across South Congress Avenue to the Continental Club to hear a band she liked. And she did just that, dressed in bathrobe and slippers.

Over the years, Katy stories like these sprouted and became exaggerated beyond belief. Many were flat lies. “I do know that my sister fueled the gossip mill with her fiery, juicy, and outrageous behavior,” Caroline says. “The focus on her physical attractiveness to men and her sexual antics were always a detraction and distraction for her to being taken seriously as a journalist and novelist. I’m sure this contributed to her pain, and in that regard, she could be her own worst enemy. As I’ve said before, her blind spot opened a lot of eyes.”

•••

The last time I saw Katy was on a rainy afternoon in a parking lot near DFW Airport. We had met for lunch and were sitting in my car afterward, before heading separate ways. She was staying at George’s house in Arlington. Katy adored her step-father, as she had her own mother, and even her stepmother: Jean Williams (Ronnie) Dugger (Bill) Marshall (Bob) Sherrill. As an extended family, it was a contender, and every time she tried to explain it, my brain froze up. But family was something Katy could neither live with nor without.

At some point in the car, with the rain spattering the windshield, it occurred to both of us that we might take our friendship to another level. It was very easy to kiss her after so many years. But the idea of starting a romance was stupid, and we both knew it. Eventually she needed to get back to George’s house. I never saw her again.

She called once or twice, having been drinking, and one time wanting to talk about either money or Cooking Light, or both. At least a decade ago, I got a postcard. I wish I had saved it. It never occurred to me that there would never be another call, another card, another slurred message with whose content I might not want to engage. On hearing the news of her suicide, I wondered what more I could have done. But I had experience with the limits of care dealing with mental illness in my own family. In that, I had great sympathy for what Caroline and Rob and other relatives had gone through over the years. And of course the rest of us who were called upon to step in. Usually we did. Katy knew it and always appreciated it. But sometimes nothing could be done. A high-functioning alcoholic is still an alcoholic. She quit drinking a few times and went to rehab at least twice. It never worked. She told Caroline, “I just can’t help myself.”

In time, I came to understand why her death had bothered me so much. “There are no heroes in this story,” Darrell told me. And I do not say so. Katy’s death shattered me, because her life was a more reckless version of my own. How many times had I moved to different jobs—magazines, teaching, newspapers, freelancing? It was what writers did. How many women had I loved or tried to love, inflicting or suffering pain as though it would all just mend, and ending up with no one? Behaved outrageously for the hell of it? It was what writers did. How many times had I and my pals wrecked a bar, prowled sordid streets, or walked through jungles and desert places drunk and disorderly, and bragged about it? It was what writers did. At least the male ones. Because as a male writer, especially in Texas, you always have to prove your manhood. For a woman? Are bad boys different from bad girls?

Katy never respected that boundary. For that she must not be forgotten, or dismissed.

•••

Five weeks before she picked up the pistol, Katy had switched to a new antidepressant. Darrell told her to get off it because it was producing psychotic episodes. But once you get into that, you can’t pull out. As a nurse, Katy knew what drinking and drugs did for depression, and how they interacted with medications. I think she also would have been familiar with the suicide (by drowning) note written by Virginia Woolf, also thought to have had depression and bipolar disorder: “I feel certain that I am going mad again. … And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do.”

On the day she died, Katy had plans to visit George and Martha at Christmas, and to go to Mexico in January. She told friends she was worried about what would happen to her because of her addictions, especially over the holidays. She told Caroline she felt trapped.

What finally went through Katy’s mind, fueled by the drinking and antidepressants, can never be known. Despite all that she had accomplished, despite the wild and energetic fullness she had force-fed into her own existence, she was finally more fearful of being alone than of being dead.

“People come into our lives,” Darrell says, “and we don’t realize how much. When they leave, there’s a void that will never be filled. Never. I never knew anyone like Katy and never will.”

•••

Instead of driving north in the rain to a funeral in Fort Worth I was still struggling to understand, I headed 40 miles southeast to the American Bodhi Center, a 515-acre Buddhist retreat deep in the thick forests outside Hempstead. It is like another world. I was pretty sure Katy would have approved.

I went inside the reception office to ask where I could sit for meditation. The staff volunteer on duty indicated a small pagoda building down a long, covered walkway. It was where he usually allowed me to sit when the main meditation hall was in use. He didn’t ask, but I said that I had come to offer prayers to a friend who had died.

He said he was sorry and asked how she had died. I used a forefinger and thumb to indicate a cocked gun and put it to my head. I bent my thumb to indicate the hammer falling.

His eyes widened. His expression indicated he understood exactly what I meant. And he simply looked at me. I knew I had come to the right place.

Rod Davis is a former senior writer for D Magazine and author of the novels South, America, and Corina’s Way. He is grateful to Katy’s friends Roy Hamric and Jan Reid and to Katy’s family for their research and support.