Dwaine Caraway may exaggerate from time to time, but he doesn’t sugarcoat much.

So when the city councilman leads a tour of his district—a rambling, woody area just south of downtown that he has represented since 2007 and lived in since the 1960s—he doesn’t show off just his success stories. He makes sure to point out the problems his constituents face, too: stray dogs, obvious drug houses, orphaned plastic bags, grown men with sagging pants. And—

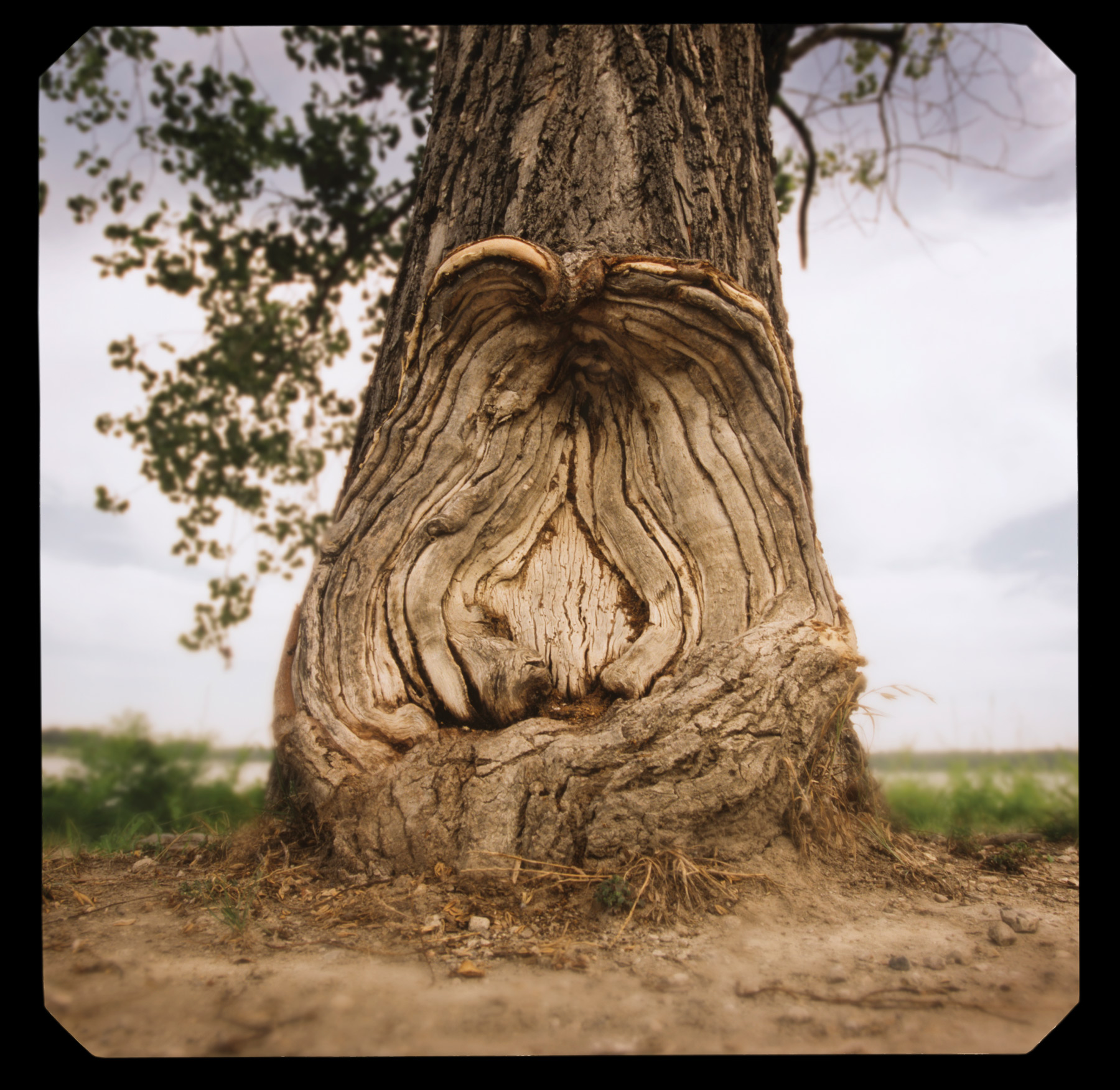

“See those trees?” Caraway asks, after pulling his black BMW 750i to the side of the road, halfway across Cedar Crest Bridge. The bridge is nestled in the Great Trinity Forest like a ribbon in an unruly head of hair.

“I want to cut all those trees back,” Caraway says, dismissively waving them away with the back of his hand, a king refusing his subjects. The scenic view is blocking what he really wants people to see: the downtown Dallas skyline and all the possibilities it holds.

For Caraway, the trees create a psychological barrier as much as a physical one. They are in the way of an idea. And if you look at it from that perspective, his animus toward the trees makes sense. He wants to see. He wants the people in his district to see how close they are to downtown, because it will make them feel part of something bigger. He needs developers to see how close the area is to downtown so they will realize its potential worth.

And that is why trees in Dallas are poised to become a racial issue. Caraway will be term-limited out of office this month, but his ideas about development will be carried forward by his successor. Much of the city’s developable land lies within District 4 and its neighbors in the southern sector. But that is also where development could do the most damage to Dallas’ tree canopy. Nearly 40 percent of it lies south of I-30, and a significant chunk of that percentage is on land where trees are largely unprotected. As much as 20 percent of the city’s total canopy could vanish, all because Dallas has never given a damn about trees.

The only barrier between the trees and a bulldozer is Article X of the city development code. But the ordinance—on the books since 1994 and misleadingly titled “Landscape and Tree Preservation Regulations”—has never offered much resistance, which is why it has been up for revision almost from the beginning. The City Council is expected to finally vote on an amended version later this year, and an update might make it harder for southern Dallas development.

But that won’t solve the city’s tree problem, because it’s not just the trees in District 4 that are in danger. They all are. In addition to a weak, development-friendly tree preservation ordinance that doesn’t actually preserve trees, there is no management plan in place for the Great Trinity Forest, and no staff in place to implement a plan if we did have one. The city has no forestry division—Dallas is one of the largest U.S. cities without one—and only hired its first forester less than a decade ago. The tree canopy is under attack in every corner of Dallas, as decades of shortsighted policy decisions begin to take their toll.

The good news is that we finally know exactly what’s at stake: an asset worth $9 billion.

•••

Mayor Mike Rawlings sat stage right, at a front table with Lyda Hill, the billionaire philanthropist who helped fund the study. Developer Jack Matthews was at another round table up front. The guest of honor, Matt Grubisich, TTF’s director of operations, was stage left, sitting with Willis Winters, the owlish director of the Dallas Park and Recreation Department.

The back of the room was largely filled with folks in baggy earth-tone sport coats that they wore like a punishment. Each table seemed to have at least one guy with a Grizzly Adams beard or a ponytail or both. Others wore logo-branded polo shirts tucked into khakis with holstered phones. You would have no trouble locating a pocketknife.

Before the findings of the report were discussed, Mayor Rawlings talked about how he loved “the poetry and science and almost theology of trees” and stated the obvious: “When you mention Dallas, you wouldn’t necessarily think of trees.” That’s why, he said, trees are so important here.

A few more speakers took their turns in front of the crowd, and then Grubisich was finally brought to the stage. He looked more at home in his coat and tie than most of the other foresters and arborists in the room, but a close observer could see that he is one of them, someone used to getting his hands dirty on a regular basis. On his ring finger, there is a tattoo where a wedding band should be, a permanent replacement after losing the real thing too many times.

Grubisich explained that he and his team—six college interns and Tyler Wright, another urban forester with Texas Trees—collected data for the report over 11 weeks in the summer. They looked at 621 randomly selected plots around the city, each about one-tenth of an acre. Each tree within a selected plot needed to have measurements taken of about 20 attributes, including total height, trunk diameter, the size of its leaf area, and what percentage of that was missing.

After they had finished their work, the data was analyzed using i-Tree’s Eco program, open-source software developed by the USDA Forest Service to “quantify urban forest structure, environmental effects, and values to communities.” The results of the Eco assessment were combined with two other studies the foundation had worked on—a roadmap to tree planting and planning, in 2010, and a survey of open space completed in 2013. They looked at the Forward Dallas plan and the Grow South initiative, transportation corridors, TIF boundaries, heat island maps, anything and everything that could possibly impact Dallas’ tree canopy. What they found:

• There are 14.7 million trees spread over Dallas’ 340 square miles of land, with 37 percent of the tree canopy located south of I-30.

• Annually, those trees provide $9 million in energy savings, capture almost 60 million cubic feet of stormwater runoff (saving $4 million in repairs), and store 2 million tons of carbon valued at $137 million.

• There are 1.8 million potential tree-planting sites in the city.

• The Great Trinity Forest is responsible for almost 20 percent of the benefits derived from trees, though it covers only a sixth of the land.

• The big one: the structural value of Dallas’ trees—based on the size, species, and condition—is $9.02 billion. “Who says money doesn’t grow on trees?” Grubisich said. It may be a corny, practiced line, but it is hard to resist.

After Grubisich finished his PowerPoint presentation, the rest of the morning’s program focused on the future, and that almost entirely centered on tree planting. The goal is to add 3 million trees to the urban forest by 2022. The foundation has already secured various partners to help with its Tree North Texas plan, targeting the Medical District, Dallas ISD schools, and downtown.

It’s a noble goal and a crucial part of any tree management strategy. But left unsaid by everyone who took the stage that morning is this: what is the city doing to hang on to the trees it already has? Dallas is not proactively caring for its trees, so it will always be playing a losing game, no matter how many trees it plants.

“You’re not preventing things from becoming problematic,” says Micah Pace, an urban forestry specialist and certified arborist with the tree care company Preservation Tree Services. He was previously the Texas Forest Service’s regional urban forester for North Texas, from 2009 to 2013. Pace was seated at a table behind me at Arlington Hall. “It’s really a question of budget and investment. Any city’s going to tell you, well, we have limited resources. Well, of course you do. But it’s one thing to say you don’t have the money to do it, and another to say we choose to do other things with our investments and resources. The city has never historically invested in the urban forest the way that they should. And it’s evident.”

The urban forest report, Pace points out, wasn’t initiated by the city. “That tells you a lot right there.”

•••

Get the D Brief Newsletter