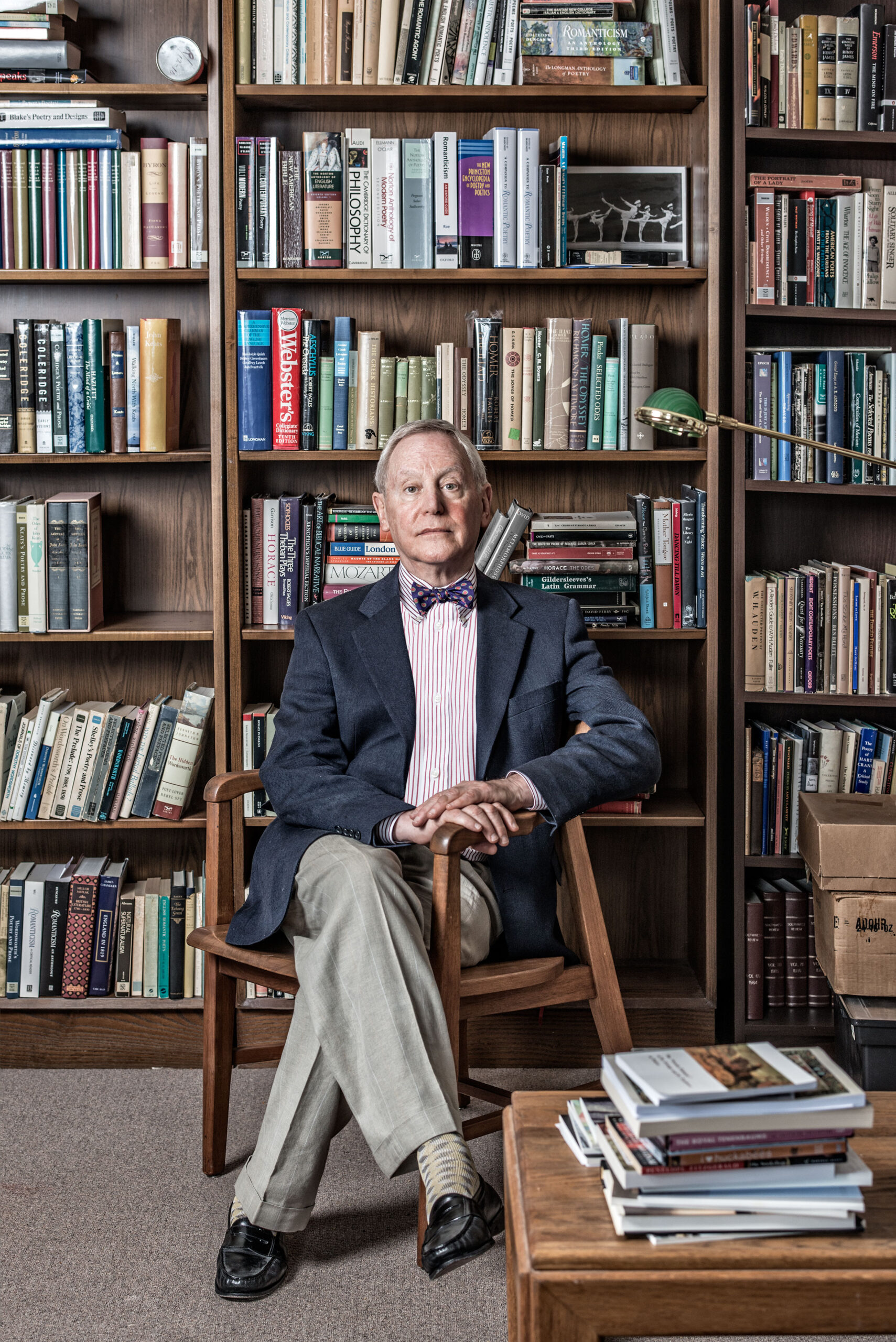

“A hundred years is a long life,” says Willard Spiegelman one warm spring Saturday in the office of the Southwest Review, the magazine he’s edited for the past 30 years. We’re on the fourth floor of Fondren Library at SMU, with a view out the window of rooftops aligned on the campus quad, oak trees in new leaf, and, far in the distance, the jumbled silver skyline of downtown Dallas.

Spiegelman, the Hughes Professor of English at SMU, is in a reflective mood, necessarily so, since his visitor keeps bugging him with questions about the 100th anniversary of the Review’s founding. It’s a fluke, a cosmic hiccup, a kink of cultural fate that the third-oldest continuously published literary review in the country is located in the heart of Dallas, where commerce is king, money screams, and living loud and large is the air we breathe. Try to imagine one of the Ewings sitting back on a quiet Southfork evening to peruse the latest issue of the Review. (Query: did we ever see a Ewing holding an actual book?) Easier to picture a blowup of Einstein’s head superimposed on the orb of Reunion Tower. Who gives a proud Texas damn about literature? (Disclosure: I was fiction editor of the Review from 2004 to 2006.)

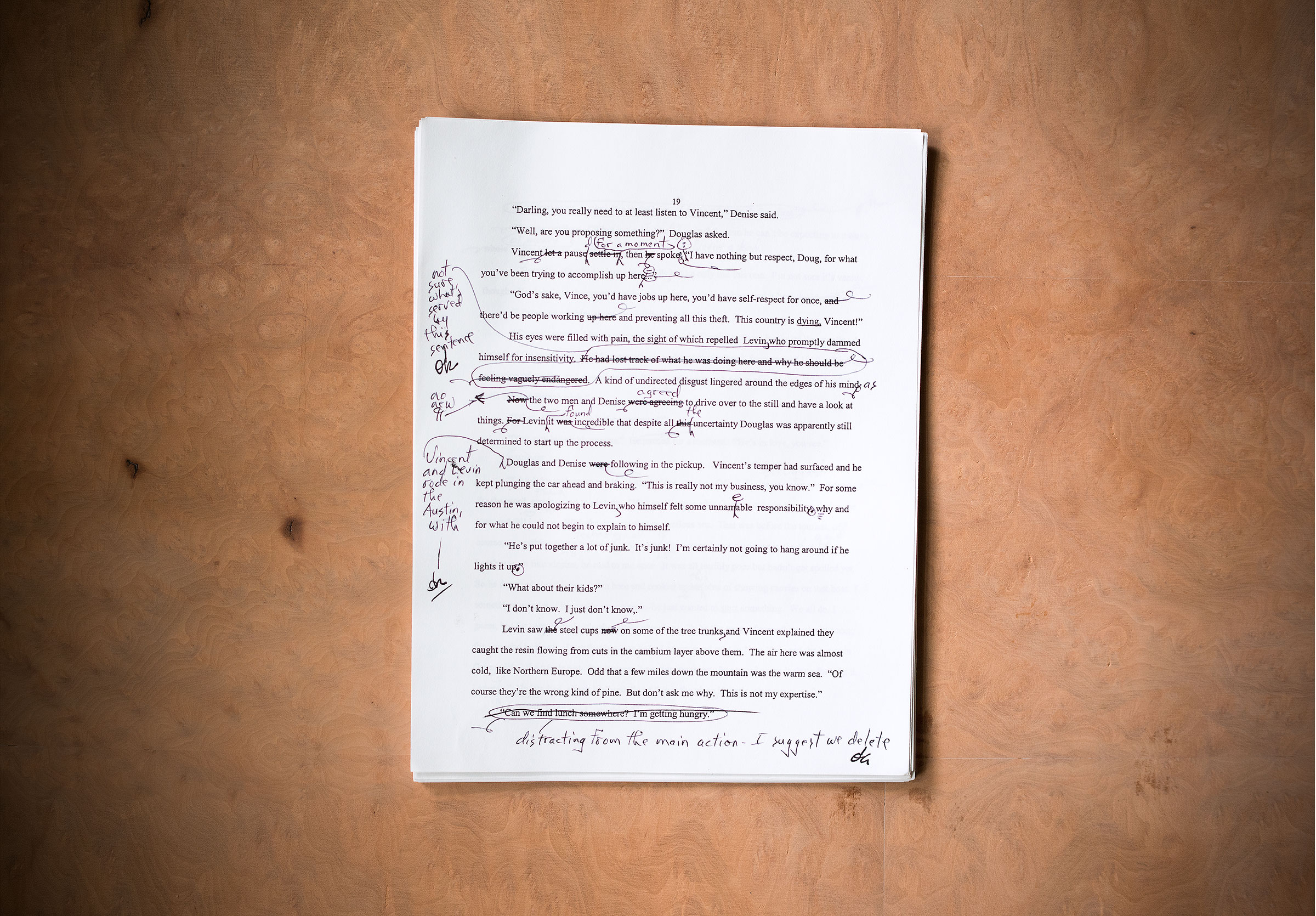

The editorial philosophy he’s applied these past 30 years has a Zen simplicity: “The Southwest Review publishes things I like to read.” Prodded, he elaborates with something of Yoda’s serenity and sense of purpose. “Good writing is writing that makes you interested in something you otherwise wouldn’t be interested in. Therefore I publish the things that amuse, interest, provoke, and move me at the moment I’m reading.”

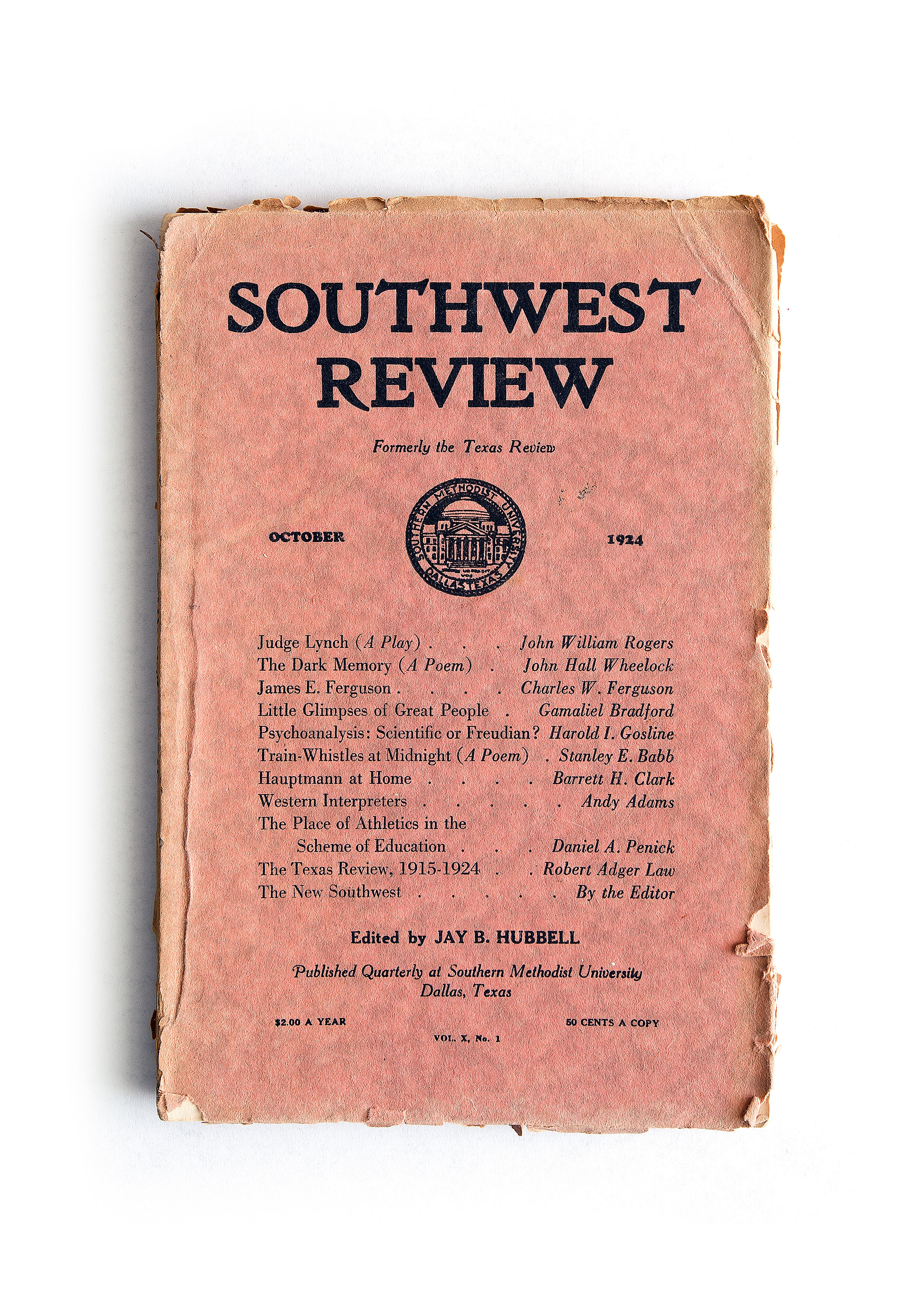

History, of course, determines what’s good enough to last. Spiegelman acknowledges that much of the writing in the Review’s early issues reads as brittle as the paper on which it’s printed. Then again, one would expect tastes to have changed in the decades since Woodrow Wilson’s first administration. When the magazine was launched in 1915 as The Texas Review at the University of Texas, founding editor Stark Young wrote that he’d been advised “to let your magazine reek of the soil,” surely (he doesn’t say this) by some sissy who’d never had his nose anywhere near said soil. “The one unusual thing in Texas,” Young continued, “seems to be the opinion at home and abroad that there is something quite unusual about us.”

In 1924, the Review moved to SMU and took its present name. The roll call of heavyweights who’ve appeared in its pages stands up to any American magazine, large or small, of the past 100 years: D.H. Lawrence, Robert Graves, Harriet Monroe, André Maurois, Julian Huxley, Robert Penn Warren, Anne Carson, James Merrill, Annie Dillard, Joyce Carol Oates, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Pinsky. Two of the greatest playwrights of the 20th century, Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, appeared in its pages. Nobel laureates, four: Saul Bellow, Naguib Mahfouz, Nadine Gordimer, and Orhan Pamuk. The Texas Trinity of J. Frank Dobie, Walter Prescott Webb, and Roy Bedichek was a strong midcentury presence, as was John Graves, author of the classics Goodbye to a River and From a Limestone Ledge. Jerry Bywaters and several other of the Dallas Seven artists were frequent contributors.

The roll call of heavyweights who’ve appeared in its pages stands up to any American magazine.

By any standard, the Review has been consistently good, at times great, and, on occasion, recklessly brave. In its first issue after moving to SMU, in 1924, the lead piece was a one-act play, “Judge Lynch,” by John William Rogers Jr., a grim tale of racism, lynching, and Southern “justice” that went on to win the Belasco Cup Trophy in the New York theater tournament later that year. The Review published “Judge Lynch” at the height of the Ku Klux Klan’s power in Dallas: the local chapter of the Klan was the largest in the country, and Klan members or avowed sympathizers held the offices of mayor, district attorney, police commissioner, police chief, and county sheriff. Ku Klux Klan Day at the 1923 State Fair of Texas broke the record for weekday attendance and featured a cross-burning ceremony in which some 5,600 men and 800 women swore allegiance to the Klan. At a time when not only blacks but also whites who stepped out of line were prime candidates for whipping, tar-and-feathering, or worse—the “torture tree” near Hutchins was a favorite Klan spot for dealing with offenders—the Review’s editors asserted their very public opposition to the thugs in pointy hats.

So there’s history. And as for the future of the Review? “I never think about the future,” says Spiegelman. “With this exception: I think about what’s going to be in the next issue.” But with his retirement from the Review set for next year, it’s natural to wonder how many more issues this stalwart little magazine will produce. The internet has roiled the old systems of publishing and distribution, upending the retail model on which the magazine relied for a chunk of its income. And the internet is changing the way we read as well. “Things come into view and disappear with the flick of a finger,” Spiegelman notes, which favors “visual grazing” over the quiet, sustained concentration of deep reading.

The fate of the SMU Press hasn’t been lost on supporters of the Review. The Willard Spiegelman Endowed Southwest Review Excellence Fund (the name wasn’t his idea) has been established with the goal of building an endowment that will ensure the magazine’s future. Donations, some substantial, have been pledged. But absent a serious commitment by SMU itself, most private donors are hesitant to commit their own money.

Spiegelman is diplomatic about all this, even peaceful, like a parent who’s raised his child the best way he knows how. At a certain point, you have to let go, and then it’s up to the kid to sink or swim. But I can’t help asking: what if the Review goes the way of the SMU Press? “It would make me sad,” he answers, “but it wouldn’t be a tragedy.” But surely something would be lost? “Nothing would be lost,” he gently insists. Nothing? He smiles. “What would happen is the cessation of a century-old process, the reflection of a region and a series of temperaments—the editors’—and a reflection of the university. For many people in the U.S. and Europe—for people who have no interest in football—it’s the one thing they may know about SMU.”

It’s tempting to ascribe Spiegelman’s detachment to his natural modesty, and to his clear-eyed vision of the town he’s called home for more than 40 years. A small literary magazine, however fine and long-lived, seems like small beans indeed in the baller Dallas of big deals, big money, big egos. And yet a less diplomatic person than Spiegelman—not as Zen, say, not as socially well-adjusted—might just be pissy enough to point out to baller Dallas that it all comes down to language. Society, civilization, whatever you want to call it, the entire system depends—literal lives depend (remember WMDs?)—on the quality of our thought and expression, our ability to put correct words to the reality of a given situation.

“Your legislator can’t legislate for the public good, your commander can’t command, your populace (if you be a democratic country) can’t instruct its ‘representatives,’ save by language,” wrote the American poet Ezra Pound in a little book published in the 1930s called ABC of Reading. “Good writers are those who keep the language efficient. That is to say, keep it accurate, keep it clear.”

Pound wasn’t talking about self-consciously fancy writing stuffed with furls and pretty turns of phrase, but rather writing that gets down into the real stuff of life, the sweat and struggle and pain and sometimes pleasure of it, the down-in-the-trenches human tumble we’re all flailing around in. Writing whose sole purpose is to portray things as they actually are: that’s a rare and maybe even radical act in an age where so much of the language that’s thrown at us is trying to sell something—a product, a lifestyle, a political agenda. The language of advertising, designed for numbing out and dumbing down. It’s a lot easier to sell us something when we’re not thinking, whereas the only thing the Review is selling is an invitation to think.

If every literary magazine in the country disappeared tomorrow, the great sucking maw of the 24-7 media machine wouldn’t so much as burp. But that’s precisely why we need magazines like the Review more than ever, as an antidote to all the baroque systems of bullshit that have evolved for the purpose of separating us from our brains. For 100 years, the Southwest Review has done more than its share of this necessary work. Here’s to the next 100 years. Let’s hope they happen.

Ben Fountain is the author of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2012. Write to [email protected].