Contemporary art has moved into the mainstream. Pop stars like Björk receive blockbuster museum shows; hip-hop artists like Jay Z brag about the blue-chip names in their collections. It seems like every time an auction house mounts a sale, headlines announce record-breaking prices. The art fair-fueled art market has made collecting contemporary art a social pastime.

Beneath the din of this often status- and money-obsessed activity, another trend has unfolded during the last two decades. As more collectors around the world amass large holdings of modern and contemporary art, they’re thinking about how to store, exhibit, and share these collections with both a limited and wide selection of the public. That has led to the growth of the private museum.

The idea of a private museum is not new. Some of the most treasured American art institutions today—the Frick Collection, the Barnes Foundation, and Dallas’ Nasher Sculpture Center—began as private collections. What is new and interesting about the latest private art spaces is their novel design, function, and programming.

In his book Private Spaces for Contemporary Art, Dallas Contemporary executive director Peter Doroshenko writes about how the freedoms enjoyed by private owners—no need to show traveling exhibitions, financial independence—allow for spaces that can skew institutional models. “[Art collections] are exhibited in unique and spectacular spaces,” he writes, “many of them designed and erected for the sole purpose of highlighting their one-of-a-kind collections, creating an extraordinary and ideal environment for the artworks.”

Doroshenko’s book highlights private spaces throughout the world, but Dallas is something of a trend leader when it comes to private art museums. From Howard Rachofsky and Vernon Faulconer’s gargantuan The Warehouse to the monastic-like retreat of Marguerite Hoffman’s Garden Pavilion, Dallas’ private art spaces don’t just showcase specific collections. They create new possibilities for the exhibition of contemporary art.

1. The Warehouse

The massive, 52,500-square-foot facility was purchased in 2011 by Cindy and Howard Rachofsky, organizers of the annual TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art auction and benefit, and collectors Amy and Vernon Faulconer. Rachofsky decided he wanted to move back into his fabled Richard Meier-designed North Dallas home, and he was looking for a new art storage facility where he could also keep some works on permanent display. By the time it opened in 2012, the space evolved into what feels like a major museum.

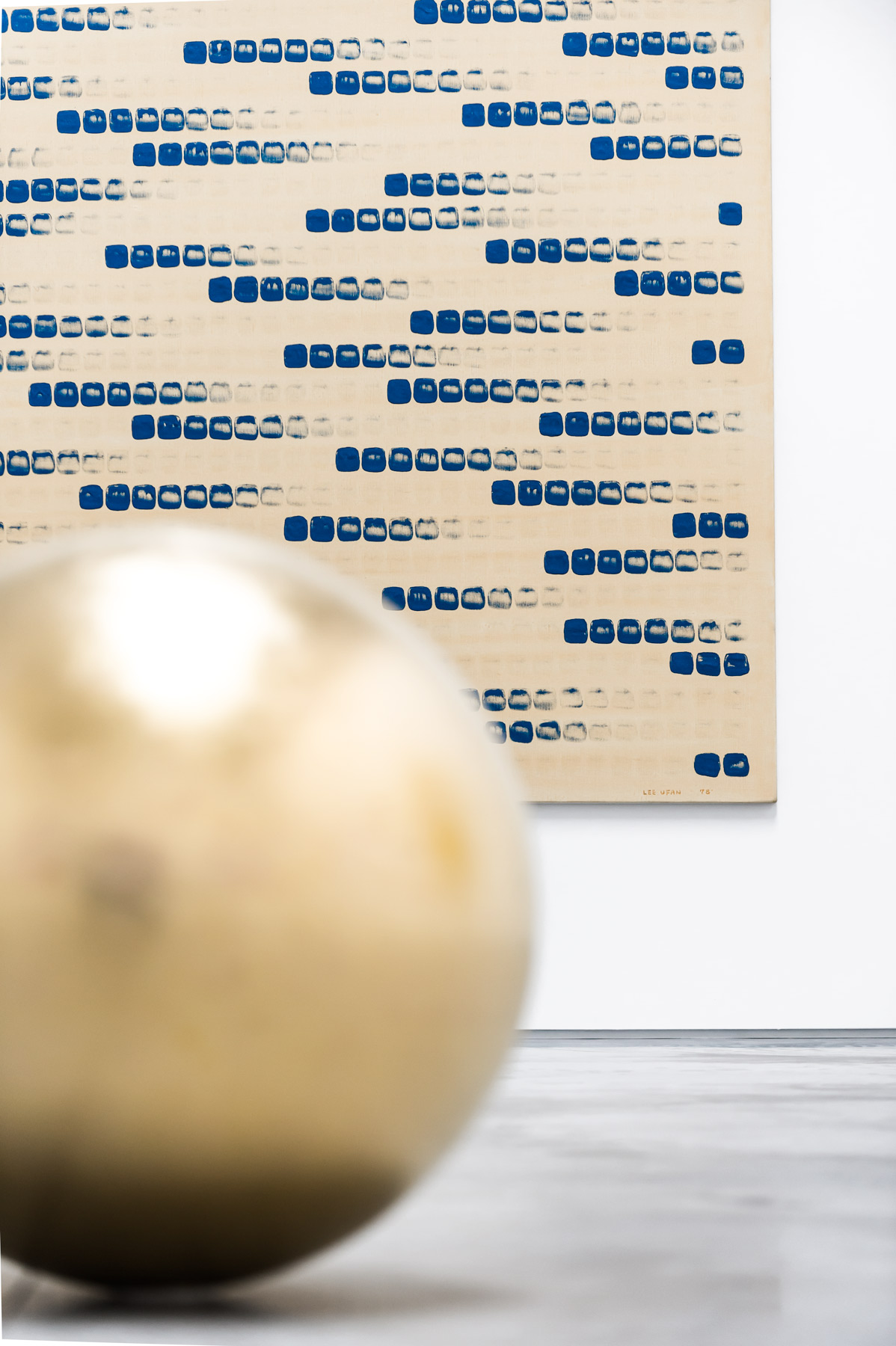

Thick white walls partition an 18,632-square-foot exhibition space dotted with skylights, which flood the interior with natural light and offer a near-ideal setting for large-scale exhibitions. The exhibition on display during my visit was called Geometries On and Off the Grid: Art from 1950 to the Present. In it, Rachofsky’s collection director, Allan Schwartzman, retraces the last 60 years of art history through the lens of minimalism and geometric abstraction, showing how these ideas shaped the thinking of artists from the United States, Japan, Italy, Germany, Brazil, and elsewhere. One novel characteristic of this show is that it pulls from numerous local collections, highlighting what is perhaps the defining trait of Dallas’ high-end collecting scene: collaboration.

In 2005, the Rachofskys and Marguerite Hoffman joined forces with Dallas collector Deedie Rose to bequeath their collections to the Dallas Museum of Art, meaning that upon their death, the collections as they exist in the moment will be owned by the DMA. The bequest sets up a unique—and occasionally complicated—relationship between the museum and its local collectors. The families now buy with the other collections in mind, looking for works that deepen their own focus while complementing the others’ holdings.

The installation in the first gallery at The Warehouse demonstrates this spirit of collaboration. The room is dominated by Hoffman’s monumental wall-hanging sculpture by Donald Judd (Untitled, 1965), while at a glance through a doorway, you catch sight of the Rachofsky-owned Richard Serra lead sculpture Close Pin Prop, 1969-76. Overhead hangs Vierkantrohre (Square Tubes) Series D (ALL BUT ONE PIECE), 1967/2009, by Charlotte Posenenske, a lesser-known German artist collected by Deedie Rose. Consisting of tubes that look like HVAC air ducting, the work snakes down from a skylight and runs across the pristine white ceiling. The sculpture is site specific, a shape-shifter, at once nestling into—and calling attention to—the particular, multilayered dynamics of the space.

2. The Pump House

Deedie Rose admits that she purchased the Pump House as an act of self-defense. For years, the old Highland Park municipal water works building adjacent to her Antoine Predock-designed home stored the town’s landscaping equipment. When the town put it on the market, she and her husband, Rusty, scrambled to purchase the building before another builder could come in and replace it with a towering manse.

Most of Rose’s collection lives in the main house, which she re-installs about once a year with the help of consultant Allan Schwartzman. The house greets visitors with a bunker-like, terraced concrete facade that, upon passing through a low-ceilinged front portal, opens into an airy, window-walled interior with a dramatic view of a lush forest along Turtle Creek. The architecture creates an inspiring dialogue between natural and domestic settings, but it can also make hanging art a challenge. “I didn’t want to live in a gallery,” Rose says. And yet works by some of the many female artists in the collection—such as an exquisite graphite on paper drawing by Michelle Stuart and colorful biomorphic fiber sculptures by outsider artist Judith Scott—exist perfectly in a space that breaks with the austerity of the white-box gallery experience.

A text piece by Lawrence Weiner stretches across the front facade of the Pump House, and a heavy-laden Richard Serra sculpture fits precariously between an exterior brick wall and the concrete walls of the holding tank. Inside, Rose’s penchant for art with personality is on display in a work by the Brazilian artist Marepe: a scaled-down wooden re-creation of a pickup truck, its bed stuffed with wooden ovens, wardrobes, and bed frames. The playful sculpture functions as a lighthearted social critique in this space, at once monumenting scrappy, lower-class junk collectors while offering an ironic, tongue-in-cheek metaphor of the art collector.

3. The Power Station

The parties here are their own kind of performance. As Dallas becomes an increasingly prominent stopover for the jet-set art world during the annual art fair and TWO x TWO events, the Pinnells’ space has become the home of the unofficial pre-party. That identity lends itself to a festive, laid-back atmosphere that is often reflected in the artists who exhibit here. The Swiss collective consisting of Tobias Madison, Emanuel Rossetti, and Stefan Tcherepnin once flooded the upstairs loft area and let the water drip down through the floor and into the ground-floor gallery where the artists performed an experimental-noise music set during the opening. Matias Faldbakken also flooded the space, only with bullet casings, temporarily transforming The Power Station into a staging ground of metaphoric violence.

Here, the Pinnells can engage with artists whose work and practice might not mesh cleanly with the collectible nature of the art market. In fact, there is rarely any overlap with the artists whom he commissions for The Power Station and the artists he collects. But Alden does boast perhaps the city’s most experimental and ambitious major collection, defined by a willingness to take chances on artists early in their careers or artists who are in dialogue with a headier brand of European conceptualism. His private collection will soon live in a new guesthouse the family is building across the street from its Highland Park home specifically to house more of the works they have accumulated.

Alden cites places like the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York as one of his major inspirations for The Power Station. Before moving back to Dallas, he was living in New York, and he treasured the excitement of stumbling into that space at random and discovering new, challenging, and provocative ideas in play. And while Alden admits his sleepy corner in Expo Park, a stone’s throw from Fair Park, isn’t as trafficked as SoHo, regular programming of screenings, lectures, and openings drives traffic and public interest to The Power Station year-round.

“Art can be intimidating,” he says. “But it should be open to anyone.”

4. The Karpidas Family Collection

At some point last year, people cruising along Hi Line Drive in the Design District began to notice a building undergoing a curious transformation. A long, single-story warehouse was retrofitted with new columns and a blue-tiled facade. There was no sign out front or any indication of its intended use. But those who had ears to the ground in the art world knew exactly what was going on. The Karpidas collection—one of the most respected and renowned art collections in the world—was coming to Dallas.

While Pauline Karpidas is often listed among the most powerful collectors in the world by Art+Auction, those who know her describe her as a warm and eccentric personality whose love of art is born not of the prestige-driven art world, but rather of a desire to immerse herself in artists’ work.

The Karpidas family collection is coming to Dallas because Pauline’s son Panos has lived here since around 2000. An aviator and former rally car driver, he is famously reclusive and media-shy. In fact, his wife, Elisabeth, who recently chaired the MTV: ReDefine auction gala, agreed to participate in this article before rescinding her offer at the request of her husband. “He feels it will always be a private space and, therefore, not relevant or appropriate for a public magazine,” she wrote in an email.

That alone offers an indication of how difficult it will be to access the space after it is installed for the first time this fall, under the guidance of DMA senior curator Gavin Delahunty. In fact, one of the most striking and refreshing aspects about the Karpidases’ arrival in Dallas is their low profile, which is a bit different from Dallas’ flashier collecting scene that often melds with the social party circuit. In other words, don’t expect the future Karpidas space to make too many appearances in PaperCity.

5. The Goss-Michael Foundation

The charitable arm of the Goss-Michael Foundation helps explain why the private space has such a public presence. Goss’ collection is born of a social nature. Beginning in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Goss moved from Dallas to London to be with former partner George Michael, he began running in circles that intersected with the then burgeoning Young British Artist movement. He says he was friends with people like Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin before he began to collect their work. Goss says knowing the artists “made it a lot easier to have access to the work and know what it is all about.”

The most significant pieces in Goss’ collection are by Damien Hirst, including his Saint Sebastian, Exquisite Pain, 2007, a cow carcass pierced with arrows that sits in a formaldehyde-filled aquarium plinth. It is one of the most representative pieces by one of the biggest art sensations in the world. In part because of the difficulty of moving Hirst’s work, it sits permanently in a back gallery at Goss-Michael, along with Marc Quinn’s rather garish, androgynous, and armless mother and child sculpture. Around these stationary works, however, swirls activity.

In recent years, Goss-Michael has evolved from a gallery on Cedar Springs in Uptown into a busy nonprofit art space in the Design District. Its year-round programming offers recurring shows of major international artists, a residency program that brings early- and mid-career British talents to Dallas for extended stays and one-off exhibitions, and a new “Feature” program that attempts to offer a platform for some of Dallas’ most promising artists. In addition to the art and the educational programming and fundraisers, Goss-Michael is home to MTV: ReDefine, an annual art auction that raises money for MTV’s Staying Alive Foundation.

It’s a lot for a relatively small converted warehouse, which has two main galleries connected by a long ascending hallway, with a small project room set off to the side. But Goss-Michael has become one of the most necessary spaces in the Dallas art scene, offering an important and rare bridge between the various tiers of the local and international art worlds.

6. The Garden Pavilion

The pavilion is a guesthouse by function, and it boasts a glass-lined living room, private sleeping suite, kitchen, and wine cellar. The layout consists of two intersecting rectangular transepts, which somewhat echo the design of the Dallas Museum of Art’s barrel vault and create an interior layout that allows each room to spill right into the next one. The result is a small gallery space that offers moments of intimacy and surprising grandeur. A Peter Doig painting on a main wall can be viewed from 30 feet away, while a tight hallway brings you right up to an inspired diptych of abstracts by Robert Diebenkorn and Philip Guston.

The installation is rotated about once a year and installed by Hoffman herself, who holds a graduate degree in art history. The collection’s most treasured artists are Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns, and the sitting area is flanked by important works from both artists. But it’s the Germans that knocked my socks off: a diminutive, playful Sigmar Polke sculpture; a Joseph Beuys latrine; a tangy Kippenberger painting; and work by Reinhard Mucha that is all post-World War II angst via newspapers submitted to acts of erasure, mishmashing the language of abstraction.

In the main house, a superstar moment: Gerhard Richter’s Kerze (Candle), 1983, a painting even non-art lovers will immediately recognize as the cover image of Sonic Youth’s seminal Daydream Nation album. It sits above a sideboard in the dining room we pass on the way to the living room to view some medieval manuscripts. Hoffman has collected these literary treasures since her husband’s passing in 2006. It might seem surprising that a collector of contemporary art would turn her attention to medieval devotional books, but in their own way, these stunning little objects express something of the joy and profundity of what it means to possess something beautiful.

I cradle a book in my hands. It’s open to a drawing, a religious scene rendered in bright blues and glistening gold set against complicated thatchwork decorated with symbolic beasts and birds. You can feel the weight of time in these objects and almost hear their forgotten owners’ breaths whispering against the pages. It creates a moment that feels ages removed from the noise of the contemporary art world, a moment of vulnerability and intimacy.