Wade Earp remembers the first time he went to the rodeo. It was more than 40 years ago, but that day is seared in his mind. He’d never seen anything so exciting. He was mesmerized by the massive bulls twisting and thrashing across the muddy arena and the rearing, bucking broncos, bouncing riders through the air. The event that he liked most, though—the one that made him gasp in wide-eyed amazement—was barrel racing. He was captivated by the riders, with their brightly colored shirts, racing those magnificent steeds around the barrels. Earp grew up in West Texas and Arkansas, and he’d ridden horses with his family, but never like this. There was something about seeing the animals and riders working together in an all-out tear, something about the speed and power as horse and human whooshed by.

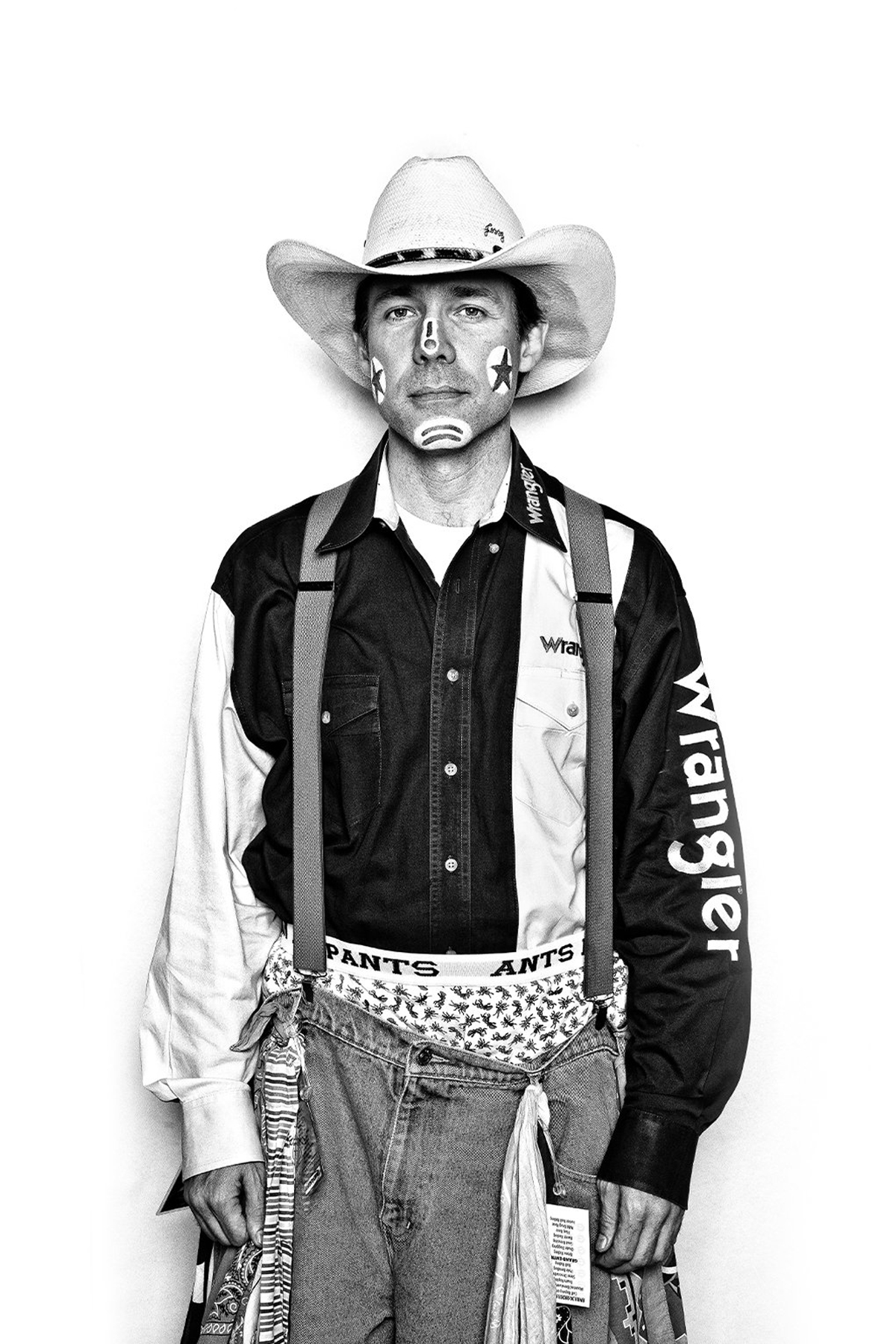

“It was like a controlled runaway,” says Earp, now 48. These days he’s got narrow, arching shoulders, tightly groomed facial hair, and, most of the time, a gilded belt buckle. He says he’s a “semi-retired” designer and antiques broker, and he lives in southeast Dallas, where he has land to keep horses. He has the aches and obligations that come with age, but when he talks about that afternoon, he reverts to an awestruck little boy. “It just looked like so much fun.”

Young Wade told his parents that he’d like to race around barrels someday, too. But his parents told him he couldn’t.

“Only girls do that,” they told him.

He wanted to know why. And he asked, repeatedly, even after his parents got tired of hearing the question. But still he wasn’t satisfied.

“Nobody could give me an absolute answer why I couldn’t race like that,” he says. “They’d just say, ‘Boys don’t do that.’ ”

This kind of thing came up in other areas of life, too. He told his parents that he didn’t like the boring, basic colors that the cowboys wore. He wanted to wear a bright purple shirt like some of the women he saw. At one point, he also announced that he wanted to be a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader. They told him the same thing: “Boys don’t do that.”

This didn’t make sense to him. The distinction seemed arbitrary. It was perplexing, because he’d always been taught to value the cowboy ethic and Western sensibilities.

“The country-and-western lifestyle is what America was based on,” he says. “It’s part of our heritage, our culture.”

He grew up watching old westerns and hearing stories about heroic cowboys. The American West is in his blood, he says. He loves talking about how he’s a distant relative of Wyatt Earp, a descendant of Wyatt’s brother, Virgil. “Wyatt didn’t have any children,” Earp says. “The only time in life he shot blanks.”

He moved to Dallas in 1984, after high school. When he came out to his friends and family a few years later, he figured he’d probably have to leave his Western lifestyle behind. He thought of iconic cowboys like John Wayne and the Marlboro Man. “That macho persona,” he says, “you just never put that and gay together.” At the time, he thought he’d have to give up going to church, too.

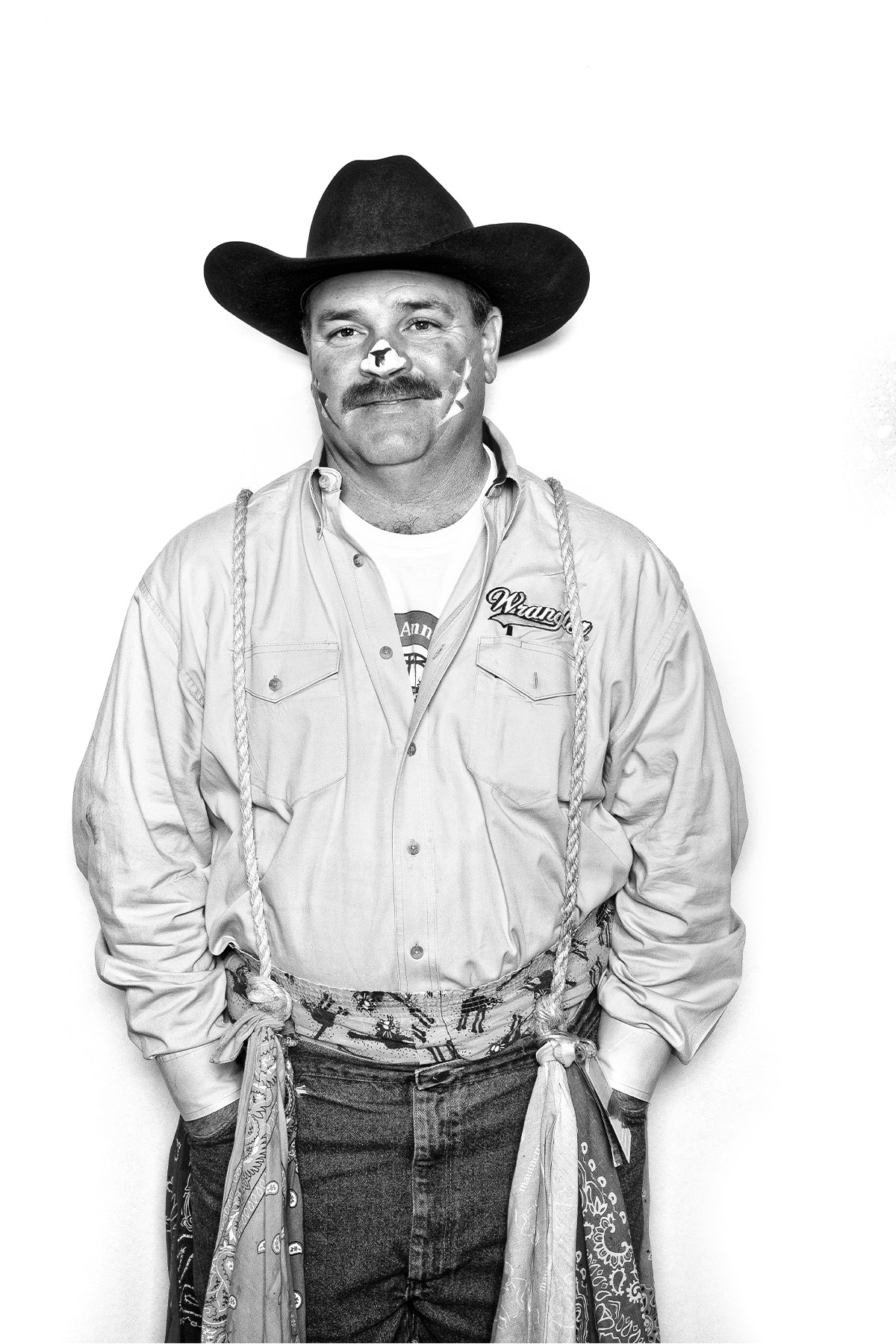

Turns out he was wrong. In 1992, he won a two-stepping contest at the Round-Up Saloon in Dallas. It was sponsored by the International Gay Rodeo Association. He went on to win a statewide contest in San Antonio and a national one in Billings, Montana. He liked the honors, but even more he appreciated the accepting environment, a place where he could be himself. A lot of the men and women he met—gay cowboys and cowgirls from all over North America—didn’t have big, accepting families. But they’d come to events like this to spend time with their rodeo families, the people who loved and accepted them, whoever they wanted to be.

Earp also learned that at the gay rodeo women were allowed to ride bulls, and men could enter the barrel racing events. The first time he entered, he didn’t come close to winning. But he loved the thrill of the ride.

“There is this absolute high when the horse and the person become one,” he says. “It’s almost like a dance. They’re doing this beautiful movement together. There’s nothing like it in the world.”

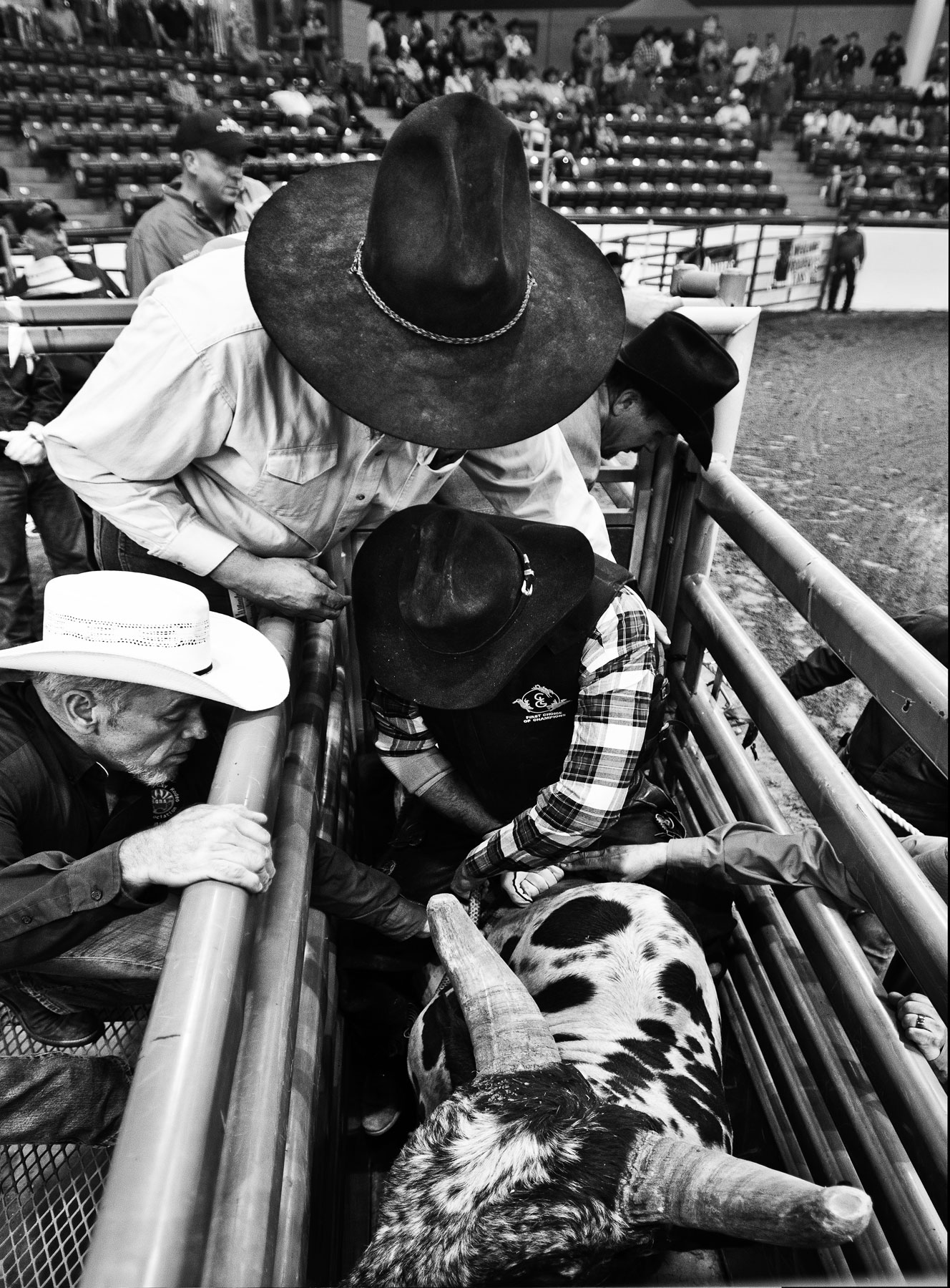

He had such a good time that he entered the next rodeo a few months later and tried more events. At first, he just liked the idea of competing, of going out there and having fun in the mud for a weekend. He liked seeing the same warm, smiling faces, and he didn’t much care about his times or his scores. But the more he worked at it, the better he got. He’d spend hundreds of hours a year practicing: roping, riding, wrestling. He entered IGRA events all over the country, and slowly he worked his way up the rankings and began winning money. Not enough to live off—he jokes that sometimes with the long drives and hard living, he felt like a character in a country song—but enough to justify the weekend trips. And after a few years, he started bringing home belt buckles, just like the ones he saw handed out when he was a little boy.

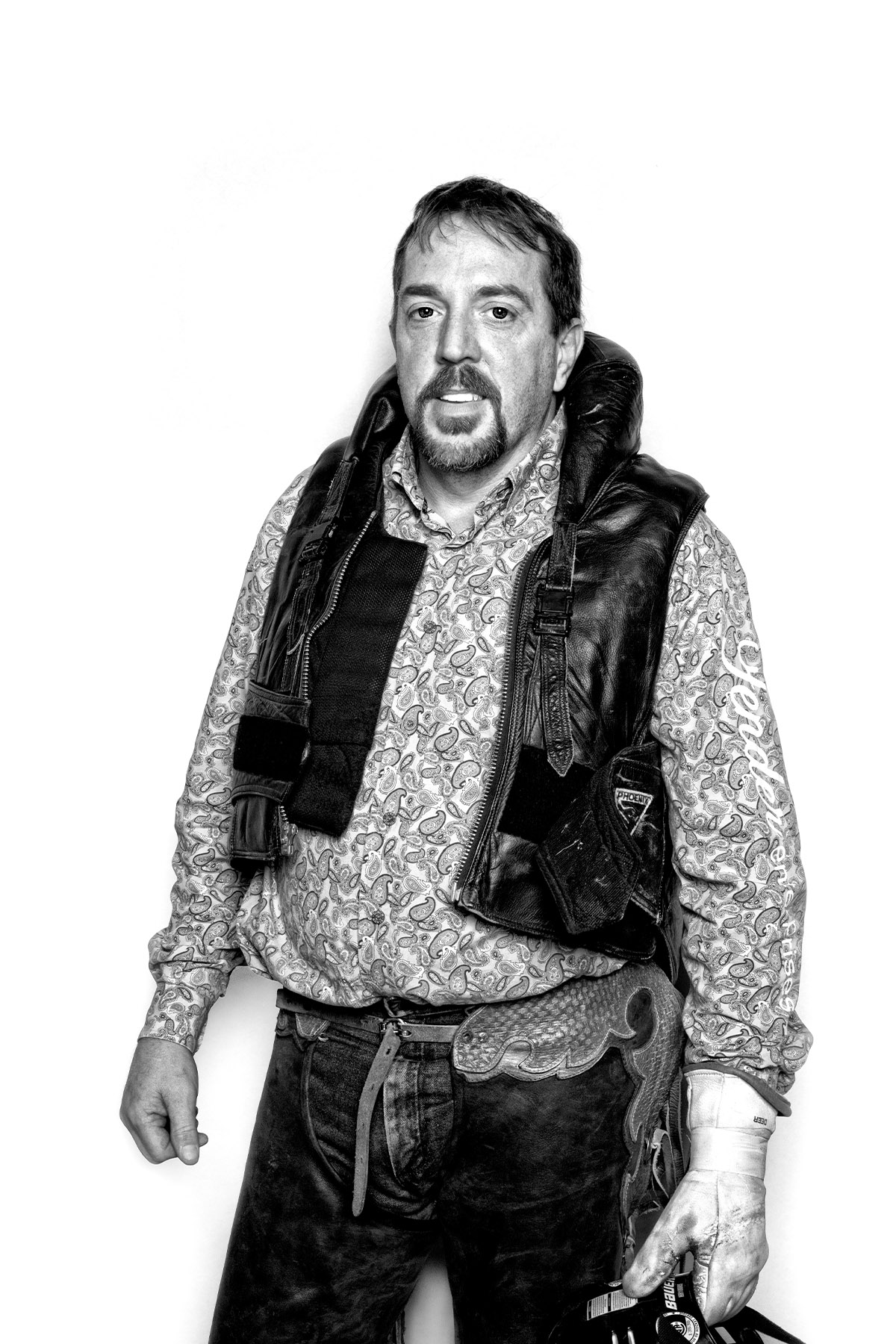

It wasn’t always a smooth ride. He’s had several major concussions. He’s been rushed to the hospital in an ambulance more than once. He broke his right arm in four places riding a bareback bronc in Chicago.

“When you climb on a wild animal, you take that risk,” he says. “Those bumps and bruises come with the territory.”

After nearly two decades of competing, at the 2011 finals, Earp had enough points in enough events to become the All-Around Cowboy—the highest honor on the gay rodeo circuit. He was the focus of a documentary, Queens and Cowboys, released earlier this year.

There was a time when he’d enter as many as 14 rodeos in a year. He doesn’t do so many now. “As we get older, our bodies don’t bounce back like they used to,” he says. He’s still out there, though, still competing in almost every event the rodeo offers. At last year’s finals, Earp took home the bull riding buckle—spinning and waving to the crowd in his bright, checked shirt. And he even does the “camp” events, the ones you won’t find at a traditional rodeo. In Goat Dressing, contestants race to put a pair of tighty whities on a disgruntled goat. In another event, someone dressed in drag has to ride a stubborn steer across a chalk line.

Though there are now plenty of corporate sponsorships, and events are still well attended—in the last few years there have been more straight couples and families in the audience—regulars say there are fewer riders. Rodeo simply isn’t as popular with younger gay men as it used to be.

Earp hopes one day it won’t matter. He wants there to be equal access to all competitions.

“I’d like to get to the point where it’s not a gay rodeo or a straight rodeo,” he says. “It’s just a rodeo. The animals don’t care. Why should we?”

Author