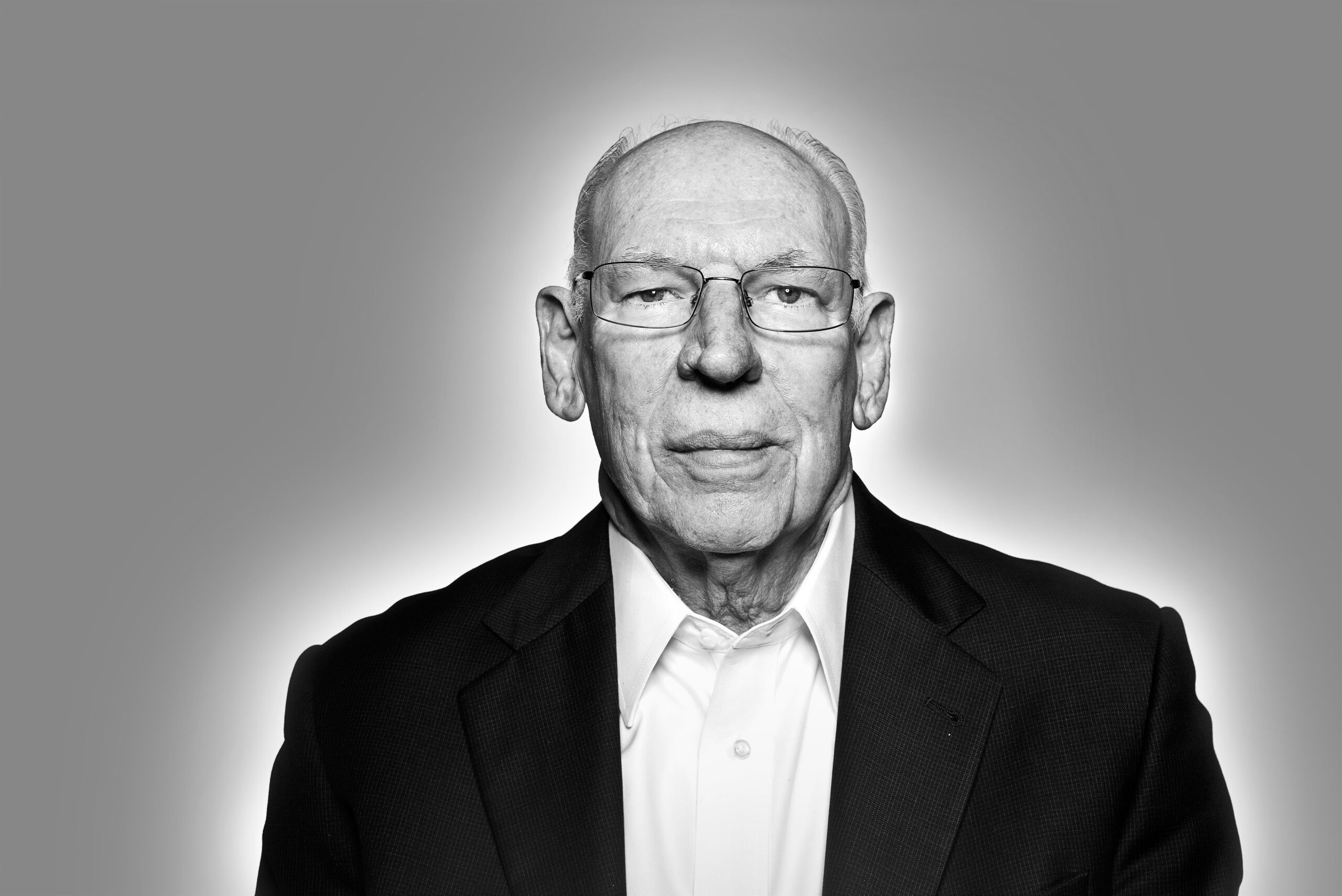

When Rafael Cruz walks into the VIP room at the River Plantation Country Club, there’s a spontaneous round of applause.

People who were sipping strawberry punch and nibbling on cheese and crackers put down their plates and cups and gravitate toward the bespectacled 74-year-old pastor. He has just arrived in Conroe, a suburb north of Houston.

The room is full of conservative politicians and powerful campaign donors. There are elected judges, state representatives, and candidates for various public offices. Standing at a table in the corner: former House Majority Leader Tom DeLay. Making small talk with a couple from Houston: Barbara Cargill, the chair of the Texas Board of Education. But everyone here wants to talk to Rafael. They want to shake his hand and have their pictures taken with him. They want to thank him for all he’s done, for the beliefs he espouses, for the way he raised his son. They tell him they are praying for him, and for Ted.

Throughout it all, Rafael maintains a gracious—if uncomfortable—smile. He takes business cards. He tries to learn names, and the names of spouses. He sees someone he recognizes and reminisces about a campaign he worked on years ago against Lloyd Bentsen. A younger man compliments Cruz’s keen memory. A woman tells him, “We’re blessed to have you with us tonight.”

“I’m blessed to be here,” Rafael says, his Cuban accent slightly bending the vowels.

Cruz lives in Carrollton now, but he spends most of his days on the road, at events like this. It started two years ago as a drive to West Texas to fill in for his son at a campaign stop and has turned into a full schedule of speaking engagements. Sometimes it’s a Tea Party group at a chain restaurant along the highway. Sometimes it’s pastors in a hotel ballroom. Sometimes he introduces Ted. Sometimes he talks for four hours and wishes he had more time. Over the last two years, Rafael has traveled the country, part ambassador, part scout, part political weapon, perpetual basking father.

The left has criticized him for comparing Barack Obama to Fidel Castro and for saying he’d like to send the president “back to Kenya.” But conservatives, including talk-radio hosts, have fallen in love with his story and his fiery, often politically incorrect remarks. Rush Limbaugh played portions of a speech Rafael gave at a FreedomWorks event in July and enthusiastically told his listeners, “This guy is knocking it out of the park!”

Tonight’s event is hosted by the Montgomery County Eagle Forum. Rafael is listed as the keynote speaker, and about 300 people have purchased tickets for $50 to $150 each. Soon it’s time for dinner, and the crowd around him builds as he makes his way to the banquet hall.

Everyone stands for a prayer. Then the pledge of allegiance. Then the pledge of allegiance to the Texas flag. As the food is served, a group called His Rain sings two songs. They’re a little like the ’90s group En Vogue, except they’re conservative white suburban women singing Christian songs. Cargill speaks briefly about her fights on the state Board of Education, and DeLay makes a few remarks, mostly about his relationship with Christ. He refers to his own indictment and conviction on conspiracy charges—and the recent reversal of that verdict—as “my ordeal.”

After his speech, he’s presented with a plaque etched with an eagle, honoring him for being a “champion of Constitutional Values.” When he sees it, his eyes light up, and for a brief second, he sounds like a little boy on Christmas morning. “An eagle!” he says. “I collect eagles!”

What country did he leave? Cuba!

Where did he move? Austin!

What was his first job in this country? Washing dishes!

Where did his mother sew his money for the trip? In his underwear!

As Cruz makes his way to the podium, he receives a standing ovation that lasts nearly a minute. He’s beloved here because he embodies the American dream. He was an immigrant who moved here legally, taught himself English, worked his way through college, started a business, and eventually had a son like Ted. And now that his progeny has become a senator and a galvanizing conservative crusader, Rafael is the father of the year, the cultivator of a great hope for millions of Americans.

And he’s not surprised. In fact, looking back now, it feels like his entire life was leading up to this.

•••

Cruz often tells the story of his journey to this country, mostly to religious and conservative groups. Ted mentioned it frequently on the campaign trail and brings it up almost every time he gives a speech or an interview. (He mentioned his father’s immigration two separate times in a 10-minute appearance on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.) The story isn’t just part of their family’s identity; it’s their trajectory. With different audiences, Rafael stresses different parts and uses different analogies, but the thrust is always the same. There’s no way to know for sure which—if any—parts of the story have been colored by the biases of memory, but each time he tells it, the old man gets emotional. He is, at turns, animated, jovial, somber.

Not long after Rafael turned 18, he was arrested as a suspected terrorist in his native Cuba. For four years in the mid-1950s, he’d worked with an underground resistance against dictator Fulgencio Batista’s government. He doesn’t get too specific about what he did. The word “bomb” comes up. He was young and idealistic back then, he says. He came from a good home—his mother was an elementary school teacher, and his father, born in the Canary Islands and also named Rafael, was a successful RCA salesman—but when young Rafael saw the way the military brutalized vocal dissenters, he was ready to fight. He says his parents had no idea, until he was arrested.

“In order to survive in a resistance movement, you have to act the opposite of what you do,” he says. “You have to act in public as the village idiot. You act in public like you don’t care at all about politics.”

Some of his cohorts had been arrested before him, as the army was cracking down. Some of them would show up a few days after they disappeared, shot dead in the streets. That’s what he expected would happen to him. Looking back, he’s still not sure why his experience was different.

“Praise God that he had a better plan,” he tells people.

He wasn’t taken to jail, he remembers. Instead he was taken to an army garrison, where the rules of habeas corpus wouldn’t apply. He says he was beaten for three or four days, then dragged into the office of a colonel. The way Cruz tells it, the colonel looked him in the eye.

“We’re letting you go,” the colonel said. “But if a bomb explodes in this city, we’re coming to get you.”

“Well, how can I be responsible for what other people do?” Cruz asked.

“I don’t care,” the colonel said. “I’m coming to get you.”

His father bought him a ticket for the ferry to Key West and drove him to the port. After the quick boat ride to America, he rode a bus for two days straight to Austin. He says his mother, worried her boy would get robbed, had sewn a pocket into his underwear. But he had only enough money for the bus fare and for a few hamburgers along the way. The first thing he did when he got to the university was go to the registrar’s office and ask for a job. Within 24 hours, he had a Social Security card. “Legal,” he stresses when it comes up. “The same Social Security Number I have today.”

He took a job as a dishwasher because, he says, he spoke little English, and nobody ever talks to the dishwasher. “They bring you dirty dishes. You wash them. You get paid.” He was also given free food at the restaurant. He could eat enough in an eight-hour shift to hold him over for the other 16 hours of the day.

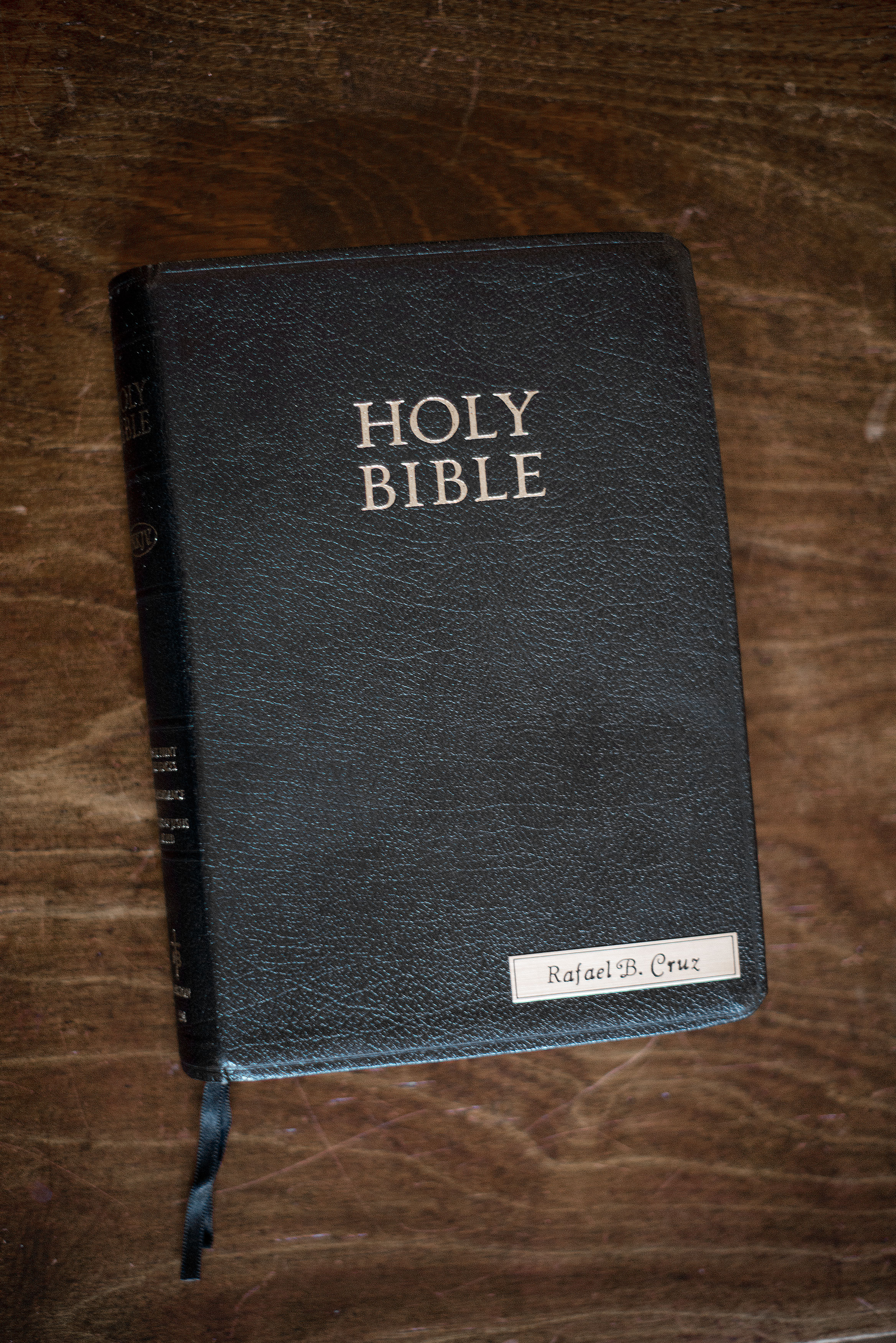

That fall, he enrolled at UT as a math major with a minor in chemical engineering. He also decided to teach himself English. In those days, he points out, they didn’t kick you out of the theater after the movie. So he could sit in the air-conditioning for hours, watching the same movies three times in a row, trying to associate words with actions and objects. He says he went every day for a month and learned the language “just like a baby.” Soon he was thinking in English, and he developed a love for American pop culture. In conversations, he randomly drops references to everything from Hogan’s Heroes to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (his second favorite book, after the Bible).

In 1959, Fidel Castro took over in Cuba. When Cruz went home to visit his family that year, he says he “got the shock of my life.” He had fought on the same side as Castro in the revolution. Not side by side, he notes, but against a mutual enemy in Batista.

Soon, Cruz says, the government began shutting down newspapers and imprisoning journalists and pastors. There was the confiscation of private property and a shift to socialized medicine. Hospitals in Cuba, he says, went from some of the best in the world to being plagued by staph infections and devoid of things like aspirin. He tells a story about how after Castro took over, soldiers would go into kindergarten classes and tell the children to close their eyes and pray to God for candy. The kids would open their eyes: no candy. But then, Cruz says, the soldiers would tell the kids to close their eyes and pray to Castro for candy. When the kids had their eyes closed, the soldiers would quietly put a piece of candy on each desk.

He says a woman who grew up in Romania heard him speak at an event in Dallas a few months ago and said that former Romanian President Nicolae Ceausescu did exactly the same thing.