The admiration he has for these masters is the feeling his cooks have for him. To them, he is that master, a source of savoir faire and tradition.

“The way I see it, there are not many chefs in Dallas who can make patés, terrines,” Liston says. “It’s a lost art for the most part, especially here in America.”

It matters to Davaillon that he’s imparting to Liston what many chefs won’t ever learn. He uses the image of luggage again. This is what Liston will take with him.

•••

Of course, he has his own teaching style.

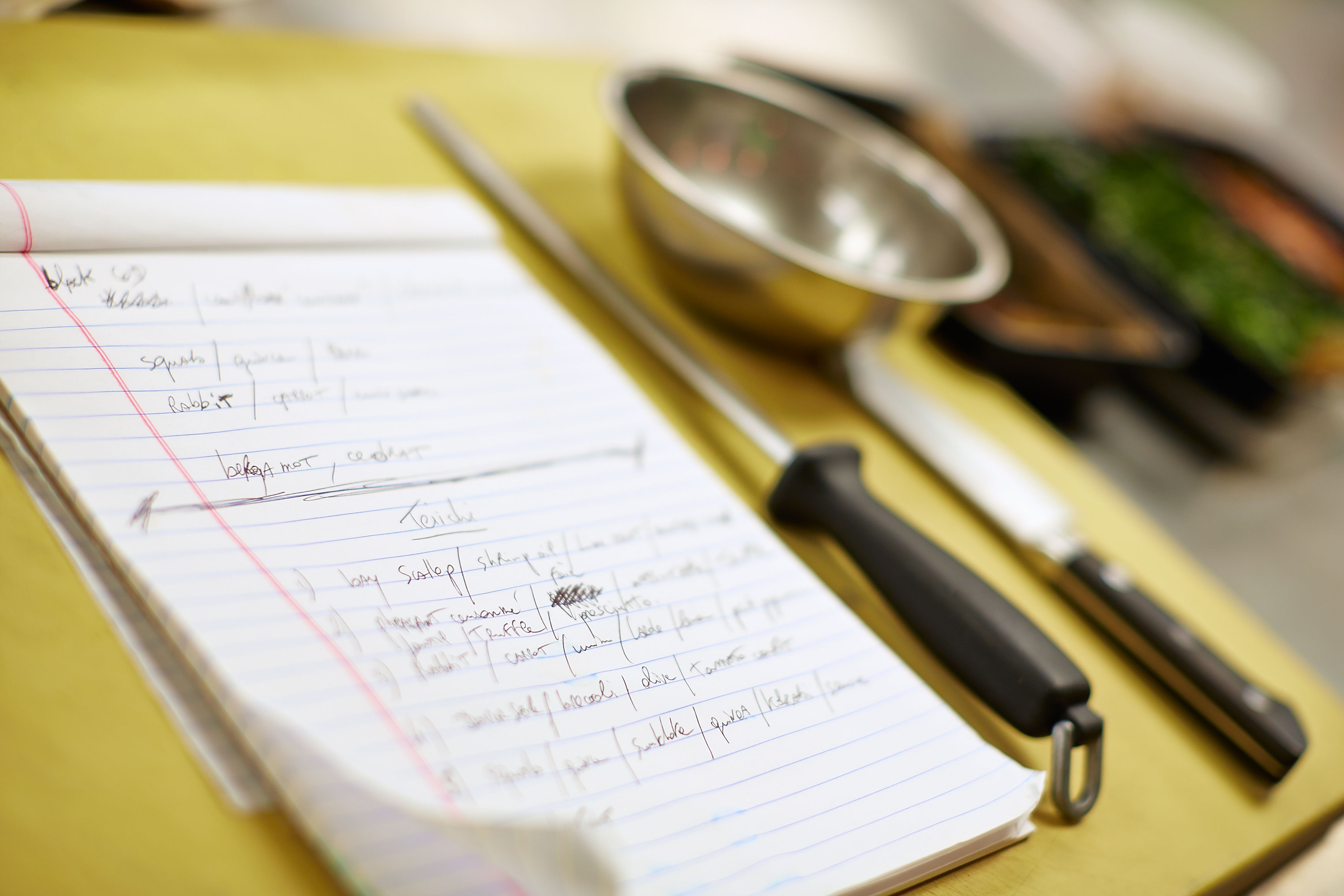

“Neil!” Davaillon calls out one afternoon, calm but authoritative. He is deep into recipe development. Things simmer on what I’ve come to dub the “experiment” stove. At his usual counter, he is stuffing rabbit thighs with a mixture of spinach, onion, liver, and tomato, wrapping them in caul fat, and delicately tying them into neat bundles that will be cooked and cut into roulades for tonight’s new rabbit dish. Liston, butchering aged ribeye on the block beside him, has been watching out of the corner of his eye. The summons comes, then, “I do another one.” This is all the preparation Liston gets before he is expected to take over. “He likes the element of surprise,” Liston tells me later. Davaillon ends the demonstration, like many others, with the word “simple,” like a period at the end of a sentence.

It means a lot to the cooks that a chef of his stature would work alongside them. “He’s right here, not hiding out.”

“People have to want to learn,” Liston says. “He only gets mad at people who don’t care.”

The care and respect are pervasive. Harms and Chastain model it at the top, each in his own way. Chastain, brusque and bear-like, will send ice crashing into metal pans or squeeze a mountain of lemons, blinking away juice spurts. But when Davaillon develops a dish, Chastain sets up ingredients, anticipating his chef’s needs and gestures. There’s an intimacy in the way he bends close to catch a word or notice a raised eyebrow. Especially because Davaillon is soft-spoken, Chastain says, “he’s not going to be the one out there controlling everything, directing everyone.” You have to pay attention.

“If you don’t have a team behind you that understands what you’re doing,” Davaillon says, “you go nowhere.”

•••

When service starts, it’s time to expedite. Davaillon stands with one hand on the counter and one hand on his hip, eyeing each dish as it’s slid across from a station. The cooks watch Davaillon intently, mostly his hands. He spies a problem with the white asparagus from across the room: “Put three. They are too small.” The corn pudding for the pork isn’t right: “Way too liquid.” For another dish: “Not enough foie.” As Harms walks by with a plate, Davaillon notices there’s a single cherry tomato missing. Harms shakes his head, frustrated with himself.

“He’s always watching,” one cook says. Sometimes, when a ticket comes in for a new dish, Davaillon shows up at the station and executes it wordlessly for the cook as an unsought reminder. “He’s like Houdini,”

Chastain says. “He just vanishes and

reappears.”

Davaillon finishes each dish. A dot of infused oil, a sprig of green, a paper-thin crisp—every dish has its accoutrement, calculated for taste, color, and texture. When the dish is finished, he gives it a final, hard stare, as though registering the picture it makes. It’s a contemplation, a confirmation, like a “yes” you can almost hear.

“I trust him,” says Susan Johnson, a server. This means a lot for her front-of-house position as liaison between the chef’s vision and the diner. “I know he’s thought a lot about each dish,” she says. “I know if there is one dollop of sauce, he wants the guest to have that flavor.”

Davaillon says he enjoys the possibility he has, in Dallas, to introduce people to new things. He does so gently, always careful not to alienate. The dynamic is sometimes poignant and funny. Some of the things that are second nature to him are the most foreign to others.

Some of the regulars give the impression that they see the Mansion as an extension of their living room. One evening, a ticket comes in for blackened chicken, carrots, and white rice with a supplement of black truffle shavings. Harms shakes his head and chuckles about the absurd order, which resembles the menu line only in that it includes chicken. He anticipates that Davaillon will roll his eyes. “He basically walked in here and created his own dish,” Harms says of the patron. At $38 for the dish and $25 for the supplement, it’s a pricey folly. Davaillon still hasn’t gotten over the behavior, he says. It wouldn’t occur to him to change a chef’s idea for a dish. But he will always oblige, if he can. Ultimately, it’s about the diners, not him. “He thinks about the people,” a cook says. This does not, however, mean meeting and greeting. When Caroline Rose Hunt, the Mansion’s former owner, dines one evening, they nudge Davaillon once, twice, to leave the line and go visit. Then it’s all so brief that I miss it. Lingering table-side is not his thing. Lingering at the table is a different matter.

•••

At the end of my 10 days, i dine with Davaillon in this room of brocade and linen where he spends so little time. I’m nervous, but it’s the only fitting way to end, to circle back to my question and see where we’ve arrived. He is not in his chef’s whites, but a crisp white shirt and dark jeans.

We talk for almost three hours. Since he was young, Davaillon says he knew he wanted to create, and he knew it would be food. “I feel lucky that I’ve been doing what I love since I was 16 years old,” he says. He promises to send photos of his father’s four-acre garden.

None of the other diners pay us any mind. I wonder if they recognize him, suspect they don’t. Davaillon dines here approximately once a year. Johnson, our server for the evening, has a twinkle in her eye as she makes a show of treating us like anyone else. She explains the dishes, as though we haven’t seen them from their inception. I order two I haven’t tried: an egg over corn pudding with chanterelles and black truffle; halibut with mussels and lemongrass-curry foam. And Bruno’s there—in the forthrightness of flavors, the way the dish sounds a chord.

In some ways, I’ve answered my question: Davaillon speaks, unmistakably—in a way that feels like both recognition and revelation. The other answer is in the plate, too: why everyone would want to be in his kitchen. If he’s here with me at the table, then his cooks are the ones who have made this food, translated a vision that’s delicate and exacting. Over a glass of Loire-Valley wine, Davaillon explains why he so rarely visits the dining room. The front-of-house told me he’s painfully shy. The back-of-house told me he’d rather be with the food. Davaillon gives me another reason: not shyness, he says, but what the French call pudeur, a modesty and restraint exercised out of respect. It’s the diners’ occasion, he says. He doesn’t want to intrude. In the best French tradition, Davaillon, at his most quiet and subtle, is a radical.