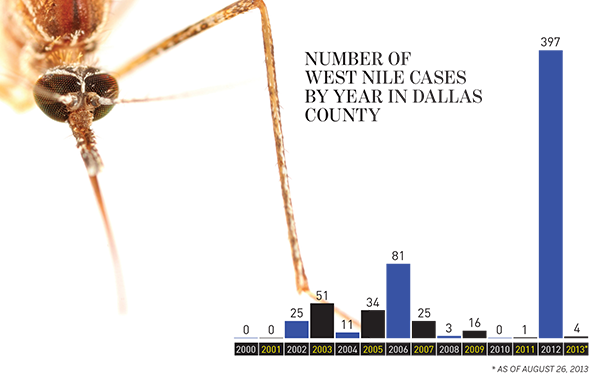

In 2010, there were no reported cases of human West Nile virus in Dallas County. In 2011, there was one. The first case of 2012 was reported on June 20. Three weeks later, there were 14 cases and one death, a man in his 60s. At a press conference, Dr. Zachary Thompson, director of Dallas County Health and Human Services, warned that Dallas was the epicenter of the country’s West Nile outbreak that summer. Officials worried that 2012 might even be as bad as 2006, when there were 81 cases.

By July 19—less than a week after that press conference—there were 26 reported cases and a second death. By Monday, July 30, there were 82 cases and five deaths reported. By that Friday, there were 123 cases and another death, the sixth of the year. It was worse than they could have feared, a public-health disaster that was drawing national attention.

On Sunday morning, Dr. Rick Snyder got a phone call that changed the course of his life and potentially the practices of the entire medical community. A cardiologist trained at UT Southwestern, Snyder was the president of the Dallas County Medical Society, a 137-year-old, 6,500-member physician advocacy group. Advocating for public-health policies is a passion for the doctor.

“We as physicians will have as much, if not more, impact on the health care our patients receive in the legislative chambers and regulator’s office than in exam rooms and operating rooms,” he says.

The call was from Connie Webster, a senior vice president at the Dallas County Medical Society. She wanted to talk about the West Nile outbreak. There was an emergency phone conference scheduled for later that evening, Snyder was told, triggered by a letter that had been unanimously signed over the weekend by an informal committee of 13 infectious-disease physicians. The group, a collection of representatives from all the major hospital systems in Dallas County, met whenever an apparent infectious threat manifested. They were calling for the immediate implementation of aerial insecticide spraying, to kill the mosquitoes that transmit the virus.

Snyder had heard a little buzz in the doctor’s lounge about the influx of cases, but he says it wasn’t on his radar. “When I heard West Nile, I still thought of Egypt.” He knew a doctor from Medical City who had contracted the virus a few years ago and was now paralyzed. Seeing a strong, healthy doctor quickly become helpless had an effect on Snyder.

“One day, he’s working 80 hours a week,” he says. “The next day, he’s down.”

The cardiologist went to work researching. He pulled dozens of papers. He looked at best practices and anything that involved spraying. He found studies about Sacramento, a city that has sprayed an urban population from the air nearly every year for a decade. He learned that the city sprayed based on the percentage of West Nile in the mosquito population.

“They’re in the disease prevention business,” Snyder says. “They don’t want to react. They want to prevent it in even one human patient.”

The 11 doctors on the phone conference that evening discussed the number of reported cases, and they looked at the projected trajectory. “We were all very alarmed,” Snyder says. “The disease takes two weeks to show up, so we didn’t know what we’d be looking at two weeks after that, and two weeks after that.” After they discussed the research, and the fact that Sacramento hadn’t reported any harmful consequences from their spraying, the doctors all agreed that spraying was the best thing the county could do.

“It was remarkable how committed everyone was,” Snyder says. “Normally, if you get 11 doctors on the phone, you’re gonna get 14 different opinions.”

The only reluctance was political, Snyder says. “I told the doctors, ‘When we mention spraying from the sky, people are going to think of Agent Orange. They’re going to think Vietnam. We are spraying a chemical over a large urban area.’ ” The next day, the DCMS board of directors (and 13 more doctors) also voted unanimously in favor of the recommendation. That afternoon a letter suggesting the county commence aerial spraying as soon as possible was sent to every major health authority in the county. A few hours later, copies were emailed to every member of the Dallas County Commissioners Court, the Dallas City Council, and to Mayor Mike Rawlings’ office.

In the five days after the letter was sent, there were three more deaths.

The decision fell to Judge Clay Jenkins, the highest-ranking elected official in the county, to declare a public-health emergency. Before making a final decision, though, he convened a closed-doors meeting of officials. The way the laws are written, each individual city must also approve its own aerial spraying. With most of the mayors either present or on the phone, the group debated the pros and cons of acting and not acting. It got heated.

“People weren’t necessarily politely waiting for other people to finish their thoughts,” Jenkins says. After two hours, he stopped and asked people to sum up their viewpoints in 30 seconds. “I was just bowing my head, thinking, praying, while I listened.”

Snyder made a compelling argument to the group. He pointed out that the chemicals used in aerial spraying are “essentially the same” as the ones used by the trucks that fog through neighborhoods most years, the same insecticide used in flea collars. “It’s a matter of 12 feet or 30 feet from your front door versus 300 feet in the air,” Snyder says. “You have a higher concentration from the street. From the air, it’s a much more equal application of the chemical.” Jenkins asked the doctor to leave while the government officials discussed the logistics. That afternoon he called a press conference to announce the spraying.

The doctor thought his role was over. But Jenkins needed someone to help explain this to the public. He asked Snyder to do television interviews, a radio call-in show on KERA, to talk to some of the city councils. Snyder went to Wilmer, where his argument was aided by the fact that he once treated a council member’s father, and Snyder’s partner had once treated the mayor.

Of course, there was resistance. Certain columnists wrote that the spraying wasn’t safe, citing a study out of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Snyder says some people misconstrued the results of that study and points to the fact that Cambridge actually employed aerial spraying in the summer of 2012. And Snyder pointed out that the only risk reported after years of spraying in Sacramento was an influx in lower back injuries.

“The first year they sprayed,” Snyder says, “they warned people: ‘If you have any concern, take any of your garden stuff or picnic tables or toys and put them in the garage.’ So dads were going out there and throwing their backs out.”

People were concerned that there was no way of knowing the potential long-term health effects of the spraying.

“We don’t know if it causes cancer 10 years down the road,” Snyder says. “But we haven’t seen that in Sacramento. We have not seen that in 10 years of spraying. We also don’t know the long-term consequence of being infected with this virus. We do know that viruses are known to cause cancer, such as cervical cancer.”

By August 14, there were more than 200 reported cases in the county and 10 confirmed deaths. Jenkins asked Snyder and a few other doctors to speak to the County Commissioners Court. Snyder, ever the cardiologist, explains it like this: “You don’t wait until you have a heart attack. You quit smoking and check your cholesterol before it gets to that.”

The spraying was scheduled to start two days later, a few hours after nightfall. Eleven cities in Dallas County had opted in for this first round of aerial spraying. There were worries about an injunction, so Jenkins went to the airport to sure it actually happened. He called Snyder. “Rick, I saw it with my own eyes,” he said. “The planes just took off.”

A few days later, Snyder joined him at the the airport to watch another round of spraying. He doesn’t remember a more satisfying moment.

“I was very satisfied,” he says. “I was feeling good about the city. I was feeling good about my family, that were being protected.”

On August 30, the first post-spraying findings were in. The city of Dallas held a press conference with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to announce the results. In the areas sprayed, the data showed a 93 percent reduction in the number of mosquitoes capable of carrying West Nile. In some of the areas that weren’t sprayed, such as Irving, the rates of human infection were higher. Judge Jenkins thanked his team, and the Dallas County Medical Society specifically for the help. Then he took his staff, members of the CDC, and Snyder for what Snyder calls “a celebratory refreshment at a local restaurant.”

Snyder says that summer was the most satisfying experience in his 25 years as a physician. “When you look at the impact we had in triggering the spraying when we did as quickly as we did,” he says, “we saved dozens of lives and God knows how many people from permanent neuro-invasive disease.”

In total, there were 397 reported cases in Dallas County, and 20 people died. There were cases all over Texas—far more than ever before—but Dallas was hit hardest, accounting for more than 20 percent of the state’s cases. The next highest was Tarrant County, which didn’t spray (and continued to see cases into September), with 259 reported cases. Because the vast majority of people who contract West Nile show no symptoms, the CDC estimates that as many as 25,000 people in Dallas County may have been infected.

Snyder wonders how many more it would have been.