Lauren Burch, a Plano mother with two children, was visiting relatives in Lubbock. Her infant son Owen became ill and could not seem to shake a viral stomach illness. She emailed Dr. Sander Gothard of Village Health Partners in Plano. He sent back instructions to Burch to see a local physician and advised the Lubbock doctor about the child’s medical background and clues as to what might be wrong. Burch says the email exchange averted potentially serious consequences.

Burch pays VHP $100 annually for unlimited email access to Gothard, and queries him about four times a month. Owen, now 2, and brother Parker, 5, generate many questions for the doctor. How much Tylenol should they be given? How high should the fever get before I bring him in? Burch, who is expecting a third child, estimates these email exchanges have prevented more than half of potential office visits. She says her husband Kevin doesn’t like to go to the doctor and uses email communication whenever possible. About 5 percent of VHP’s patients pay for the extra access.

Welcome to 21st century medicine. VHP was the first family practice in Texas to become a federally-certified patient-centered medical home (PCMH).

Health-care experts are placing a lot of faith in medical homes. The term is off-putting to some because it sounds like “nursing home.” However, it is simply a physician’s office organized in a different way.

The PCMH recognizes that health care is rarely one doctor treating one patient. It requires a team of health-care providers, educating family members, and using community resources. Physicians are more like team leaders, coordinating care with staff members, as well as specialists and hospitals. The doctors are rewarded more for keeping their patients healthy and out of the hospital, rather than for short face-to-face visits with a lot of tests and procedures. Medical homes often are paid a monthly fee for patients under their care.

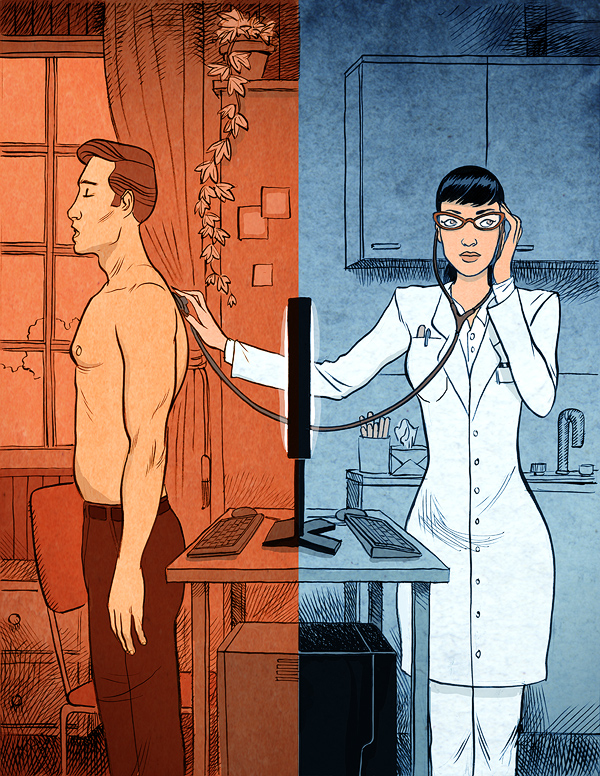

The “patient-centered” aspect assumes patients will participate in their own care. They will ask for and receive the care they want and need, and act on the medical advice they are given. The medical home has a number of features that are missing in most doctors’ offices: electronic medical records, email communication, remote monitoring of chronic conditions, and frequent reminders about preventive care.

There are many strengths to this kind of approach. Physicians have fewer incentives to provide unnecessary care, and participants recognize that most patient transactions can be handled by email or telephone. A Mayo Clinic pilot study found that “e-visits,” or care provided by email, made office visits unnecessary in 40 percent of the cases.

A 2010 Health Affairs article described the future physician’s office using medical-home principles. The office might treat 100 patients a day. The doctor might be involved with 30 to 40, of whom perhaps 10 would have traditional face-to-face individual appointments. The other patients interacting with the doctor would do so by telephone, email, or group appointments. The remaining 60 to 70 patients would be treated by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or medical assistants. They would handle less complex cases and counsel people with chronic conditions on disease self-management. These team members would spend more time—and likely be more effective—than a physician could be in a 15-minute time slot.

The traditional doctor’s office currently is set up to deal with brief illnesses or disease that can be cured mostly by time and medication. It is ill-suited to treat chronic disease, which accounts for about 75 percent of health-care spending. Effective chronic-disease management requires close monitoring and treatment tweaking to avoid complications such as heart attacks, stroke, or respiratory failure that require hospitalization or emergency department visits. Medical homes typically have after-hours arrangements for their patients to be able to see a physician or nurse without going to the emergency room. Less than one-third of doctors’ offices have such an arrangement now.

Currently, an estimated 40,000 primary-care physicians work in practices set up as PCMHs. That is about one out of eight physicians and pediatricians. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan said it saved $65 million to $70 million in 2010 working with PCMHs. It paid an extra $7,500 per physician for the year. However, it saved money because better care yielded fewer hospital and emergency department visits. The doctors also ordered more generic prescriptions because electronic prescribing allowed them to see lists of covered medicines.

Convenience and Care Coordination

Gothard and Dr. Christopher Crow are two of Village Health Partners’ seven co-founders. Crow, the practice’s public face, is an evangelist about making health care accessible, convenient, and of high quality. He has a master’s degree in business administration and the outlook of an efficiency-minded executive. VHP was an early adopter of electronic health records, buying its first system in 2003. Crow estimates the $100,000 investment paid for itself in 18 months.

VHP has leveraged technology and standardized processes to lower its support staff well below the national average. The average family practice employs 5.5 people to support each physician; VHP can do so with a ratio of less than 3.5-to-1.

Although VHP is recognized as a model medical home, Crow is much more enthusiastic about the practice’s location: Legacy Medical Village. There, 23 medical specialty practices plus seven service providers operate under one roof to take patient convenience and care coordination to an even higher level. Patients can see a doctor, fill prescriptions, get lab and imaging services, and even see a consulting surgeon in less than half-a-day without leaving the 100,000-square-foot facility. Crow calls this Health 2.0, where 95 percent of necessary care is at one location.

The success of VHP and Legacy Medical Village certainly begs the question: Why there are not more medical facilities such as these? Crow talks about the need for “physician leadership,” which is shorthand for the willingness to invest in electronic health records, assertively coordinate care, and have a passion for customer service.

“Those are not the skill sets you generally find in a Marcus Welby shop,” Crow says, referring to the iconic television physician played by Robert Young in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Tom Banning, CEO of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians, agrees: “From where I sit, the opportunity to reform their practices for value and quality is there for the physicians’ taking. It takes visionaries to step up to the plate. It’s not just investment in EHR. They need to be able to capture data and be willing to measure themselves against their peers to improve.”

VHP has 14 primary-care physicians, as well as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, medical assistants, a dietitian, and diabetic educator to serve more than 40,000 patients.

Emphasis on Personal Service

Louann Dunkle, 54, a teacher at Haun Elementary School in Plano, was diagnosed with high blood pressure two years ago. Her physician urged her to lose weight to control it more naturally. VHP dietitian Melanie Wilder taught Dunkle to count calories and keep a food journal. She has lost 75 pounds and has been able to shed two of her three hypertension medications.

“Even though it’s a big practice, I really feel like they care about me,” Dunkle says.

Each day, the busy practice sees 250 patients and receives about 700 phone calls, 400 faxes, and 100 emails. Phone calls are usually answered within 30 seconds. There is no voicemail or phone tree.

Crow estimates the medical assistants can handle 90 percent of patient phone inquiries without handing them off. They also use electronic health records to remind callers about preventive care.

“We have more than 1,000 opportunities a day to check for gaps in care,” Crow says. “We organize our practice around those opportunities.”

VHP’s clinical quality metrics reflect the results. For example, its breast-cancer screening rate is 79 percent, compared with the national average of 43 percent. It also exceeds national averages in colorectal cancer screening, smoking-cessation counseling, and diabetes control.

The practice also monitors emergency department visits by their patients at local hospitals, proactively calling to create discharge care plans. Crow says hospital emergency rooms rarely communicated with VHP about patient care prior to the monitoring.

The strategies are getting Village Health Partners some recognition. It was named the Practice of the Year by Physicians Practice magazine in 2006. The Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society named VHP the nation’s most adept physician practice at using technology and medical records in 2007. Its village concept has attracted visitors from the state legislature and U.S.Congress; Crow also was asked to visit with Obama administration officials in Washington, D.C.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas created a medical-home pilot project in 2010 with VHP and the Medical Clinic of North Texas. Rick Haddock, senior director, says VHP was chosen because it was “technologically savvy.” He expects the initiative to be renewed in 2012 because, “Overall, we are very pleased with the outcomes.”

Banning, of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians, says, “[VHP] is a unique and cutting-edge practice. They really have been able to harness the technology piece, but it is also tried and true team management care for patients. The model is having a primary-care foundation and invited medical specialties in the same physical location with similar EHR and a mission of accessibility and efficiency. That doesn’t really exist anywhere else in Texas and is rare nationally. What they’ve been able to do is nothing short of spectacular.”

Lauren Burch is a raving fan, too. She says some of her friends have switched to VHP after hearing her extol its medical home approach. She likes the electronic health records access in the exam room because “it’s fast, accurate, and all right there on the screen. And if we have to wait for the doctor, they pop a movie into the computer and my kids are good to go.”