Someone should make a television show based on the life of Dr. Duke Samson. America would love a character like this. He’s 6-foot-2 but seems several inches taller. He embodies his name, Duke, as if one of John Wayne’s characters had grown up to be a doctor. At 69, he walks with the swagger of a West Texan, sometimes reviewing cases with a cigar in his mouth, casually calling people he’s just met Ace.

His voice is deep, gentle, almost always calm and measured, but it’s often said that he doesn’t suffer fools gladly.

Maybe the TV show is set in Dallas in the ’80s, and there are a lot of fast muscle cars and flashy ’80s clothes. It would be cool if the opening credits showed the doc walking down the hospital halls, his cowboys boots clicking beneath his scrubs, as women swoon and orderlies give him high-fives. I’ll just throw this out there now, and we’ll touch on it again later, but I think there should be a magazine writer character somewhere in the show, too. He’d want to write a story about the doctor, but he’d do it as a long pitch for a new TV show set in the ’80s.. He’d have an editor—yes, this sounds like a tangential plot line for so early in the pitch, but I think you’ll understand why it’s important later—and the editor would initially like the idea of the TV show thing, but he would find it tiresome and gimmicky as the story progressed. So the writer would rewrite the story with much less of the TV stuff and more shape and narrative to it, but then, right before turning it in, he’d go the other direction and put a whole bunch more of the TV show stuff right up front. It’d be ridiculous and way too meta for readers. So that’s all going on. Meanwhile, it’s mostly about this Duke guy.

He played high school football in Odessa, Texas, the town that gave us Friday Night Lights, and went on to play at Stanford. He played rugby and once faced off against the famed New Zealand national team known as the All Blacks. He’s a skilled horseman, an avid gun enthusiast, and a part-time boxer. He served in the Army Medical Corps at the end of the war in Vietnam, he’s parachuted out of more than a dozen planes, and he once medaled in a taekwondo tournament in France. He also happens to be arguably the best brain surgeon on the planet.

Duke wrote the book on aneurysm removal, a manual doctors around the globe still consult nearly 20 years after its publication. The techniques he developed are regularly discussed at international neurosurgery conferences. His is known simply as The Southwestern Method. He is the chair of the neurosurgery department at UT Southwestern Medical Center and performs most of his operations at the associated hospitals. Medical students come from all over the world to study under him. Highly accomplished doctors call him “the most calm, collected genius ever to step into an operating room” and “some sort of god, walking around among mere mortals.”

Of course, the real Duke Samson is too busy to watch TV (except for the occasional Cowboys game), but he’s the kind of character who could tell a new, amazing story every week. One episode could be about the time a hospital administrator came into Duke’s operating room and said something he shouldn’t have. As the legend goes, Duke stayed cool at the moment. But a little later, in the locker room, he was holding the administrator up by the collar, conversing loudly about the transgression. The administrator, far from being upset over the incident, bragged to people that he’d been set straight by the great Duke Samson.

Another episode could be about the time he came to the rescue of a Turkish dwarf. The patient, a baker from Turkey living in Abilene, Texas, had been diagnosed with an achondroplastic dwarf mutation. He was in for a complicated procedure with his spine. The surgery took a turn for the worse—there was a lot more bleeding than anticipated—before Duke swooped in from nowhere. He told the doctors in the operating room to go to lunch. They protested. No doctor wants to leave a patient midsurgery, especially during a critical phase. But it was Duke. They left and he scrubbed in, and when they came back from the cafeteria, they found the problems rectified and Duke finishing up the operation.

There could be an episode about the time Duke was at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C.—he still does a lot of work with the local VA and the one up there—when a special agent, who’d been shot by a sniper, came in. The bullet, fired from above, out of a Soviet Dragunov sniper rifle, went in through the agent’s left eye and out the back of his head. Less than 24 hours after he’d been shot, the agent was stateside, barely alive.

“There’s a neurosurgeon downrange, right there,” Duke says. “They get the thing cleaned up, and they get the bleeding stopped. They put a compressive dressing on it, and they put your ass on a plane and you’re at Walter Reed the next afternoon.”

The chances of survival were slim, and managing all of those issues at once—the entrance wound, the torn tissue and splintered bone, the profuse bleeding, the gaping hole in the back of the skull—was just about impossible. Duke didn’t treat the man, and he can’t talk about his patients, but these are things Duke can do. The special agent will probably be blind in both eyes, but he lived. He. Lived.

“He’s gonna walk out of that hospital,” Duke says.

In this line of work, there is no margin for error. A slip of 3 millimeters could mean the patient never speaks again. And there are so many precarious obstacles in the brain. A skilled neurosurgeon has to be a little like Indiana Jones, “except Indiana Jones doesn’t know where he’s going,” Duke says.

He can come off as cocky sometimes—“the bravado of a star quarterback or an astronaut,” one co-worker calls it. That’s just confidence, a by-product of the courage required to saw someone’s head open and pry through his brain.

“Fear is the worst enemy,” Duke says. You just have to block it out. “It becomes easier the more you do it. If you are entranced by the physical act, it helps put the rest at bay.”

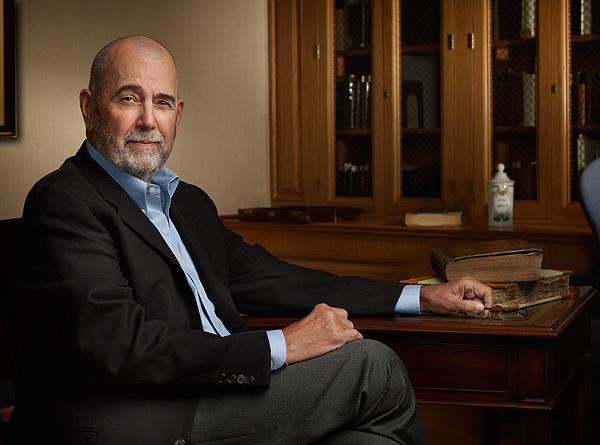

Perhaps the first episode of the TV show should be about the time a magazine writer went to Duke’s office to interview him. As the door opened, Duke, dressed in scrubs, turned down the Gregorian monk chanting coming from a desktop radio. There was an ice-fishing pole on a shelf near degrees and awards and photos of his family. A plastic skull covered in pink marker sat on his desk. On the walls hung a framed Ansel Adams photo of New Mexico and a shot of a tranquil Montana lake that Duke took himself. He dabbles in photography. A sleeping bag sat ready on a leather couch, for those times when operations go so long that he has to sleep at the hospital. And, behind him, a 13-inch television streamed footage of an aneurysm surgery under way in the operating room a few floors below.

On the screen, the brain sat glistening, pulsating ever so slightly with each respiration. “There it is,” Duke said, just a bit

of awe in his voice despite the thousands of brains he has seen. No matter your philosophies on life, he said, that 3-pound slippery loaf is who you are. “That’s why you can never have a brain transplant,” he said. “You can only have a body transplant.” He gestured toward the screen.

“That’s all there is. The rest is just appendages.”

He pointed out that for all we still don’t know about the brain—and that’s a lot—what we do know is incredible. “The things the human brain is capable of,” he said, “it’s so fascinating.” Not only can it write Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and calculate a series of complex movements no computer in the world could even begin to navigate, but it can contemplate a fictional surgeon on an imaginary television show while a real doctor talks about what a brain can contemplate—and it can contemplate itself contemplating all of that.

It’s this setting, this challenge that has kept him interested for so many years. His wife is Dr. Patricia Bergen, a trauma surgeon at UT Southwestern. Their first date was in 1988, not long after Duke was the focus of the first ever episode of 48 Hours. She sees the long hours of preparation work he puts into the job. When he has a big case on Monday, he’s already thinking about it and reading up on it Saturday afternoon. Their life together has involved a lot of balancing schedules. They never had time for the traditional family dinners, but they always made their vacations, which often lasted a month in the summers, an important part of family time.

“He’s also one of the best dads on the planet,” she says. They have two sons, ages 22 and 20. “There are a lot of myths and legends about him, but Duke is just a great guy who always does the right thing.”

Back on the TV screen in Duke’s office, the most complicated part of the surgery was about to begin. The patient had an aneurysm, a compromise in a blood vessel that’s a little like a blister in your brain. The goal, after peeling back the muscle tissue and removing part of the skull, was to get to the blister and clip it with a clasp about the length of a fingernail.

When he’s in the operating room, Duke often wears his trademark American flag bandana. As he’s scrubbing in, he might tell a younger doctor, “Get your light on, Ace.” Before cutting into the scalp, he’ll ask a nurse, “You kill all those nasty germs?” And as he wrestles to remove a spongy tumor or to clamp and drain an aneurysm, he’s been known to swear at the maladies.

“If you just walked in and saw it and heard this guy cussing out this tumor, you’d think it was pretty strange,” says Dr. Babu G. Welch. Welch is another prominent neurosurgeon in the same practice. He is laid-back, a whiz nearly half Duke’s age who not too many years ago was still studying at UT Southwestern. He thinks of the older surgeon like the Tommy Lee Jones character from No Country for Old Men.

“He’s very linear, very straightforward,” Welch says. “He’s very efficient with speech. If he means to insult you, you will be insulted. If he means to compliment you, which is less often, he’ll do that, too.”

As the surgery progressed on the screen in his office, Duke went through the finer points of his legendary bio. For all the lore, he was remarkably humble and courteous. He has always been willing to try new things, to test himself in new ways, he said. But he was only really exceptional at one thing. That’s the way his brain works.

He explained that he often has to correct people and tell them that while he was on the Stanford team, he was not an All-American football player. He was actually rather slow. And when he played rugby against the New Zealand national team, they pummeled him.

He told the story about the time he was followed on his way home. He was riding his bicycle from the hospital to his house, near SMU. There had been a string of robberies in the neighborhood, and the criminals were following people home and going in through their garages. One man had even been murdered. It was dark, and the streets were mostly empty. As he often does, Duke had his .45 with him.

He noticed a pickup truck. When Duke turned, the truck turned. When Duke went down the alley behind his house, the truck turned in behind him. As he neared his garage, he slowed down. The truck slowed down. Duke could see there were two men in the cab. He rode past his house, then stopped. The truck stopped, too. Finally, cornered in the dark alley, Duke pulled his gun and told the two guys in the truck to put up their hands.

It turned out they were there to clean the neighbor’s pool. Duke apologized and, with the help of his neighbors, explained about the robberies and the murder and the tension. The pool guys understood. Soon, Duke brought out some cold beers, and a situation that could have been terrible turned into something the neighborhood still laughs about today.

Then Duke told the story about the time he was biking to work through a rough part of town, and saw a guy out in the middle of nowhere beating a woman. He pulled out his gun—“my reason for him to stop what he was doing,” Duke called it—and sent the man on his way. When he asked the woman if she needed the police or any medical attention, she just yelled and swore at him. “That’s what you get for trying to help

people,” he said.

His wife says that, despite all of his crazy adventures and tough demeanor, he isn’t afraid to show his emotion. He can get pretty low when he loses a patient. She also remembers him tearing up both times their sons left for school. And, every so often, when he thinks about his dad.

Duke never really thought much about brains when he was young. He liked sports, anything that allowed him to compete. When he realized he wasn’t going to become a professional athlete, medicine sounded like a nice backup. The challenge of learning how the human body functioned was alluring, as was the chance to compete intellectually with some of the smartest people in the country.

He says he’ll stop working only when the challenges of surgery no longer captivate him. But not long ago, he announced that he would step down as chair of the neurosurgery department. For 27 years, he has built one of the more respected programs in the world. He has worked on famous people he can’t talk about, and he has changed the profession forever. He’ll still operate and see patients, but his days of fundraising and being the primary advocate for new equipment and more in-depth training are over, he says. More time for adventures.

Once the Duke character is established with the audience, there could be an episode about a new endeavor he’s undertaking: writing a novel. He has always been a voracious reader, everything from Hemingway to history to new books about the war in Iraq. So he figured he’d try his hand at writing, too.

“Why not?” he says with a grin.

The book is tentatively called Grey Dogs, and it’s about a bank robbery that happened when he was stationed in the Philippines. The characters are based on Duke and a few of his buddies. He has an editor who likes the concept, but Duke has found that getting the brain of a reader to engage with even very interesting characters can be tricky. In all his life, he can remember giving up on only one thing—learning to play classical guitar. So he’s not going to quit. It’s just that writing is harder than he expected it to be.

Of course, he points out, it’s not brain surgery.

WRITE TO [email protected].