Eventually, a judge ruled against the City Council, deciding that it would be unconstitutional to keep the books off shelves. But by then, most people in town just wanted the story to go away. Church attendance slowly increased. The congregation built a new, high-tech sanctuary with lots of room and ample parking. And even as donations at other Southern Baptist churches were declining, his collections went up. It was a lesson he wouldn’t soon forget.

Around that time is when Reverend Barry Lynn first heard of Robert Jeffress. Lynn is the executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State. In 1998, he wrote Jeffress a letter, asking him to give back the books and stop his campaign.

“These people,” Lynn says, “their agenda is to take over your life from the moment of conception to the moment of death. If they have their way, people are literally going to be treated like second-class citizens. If you don’t object at every opportunity, one day it may be too late.”

More recently, Lynn has written to the IRS, suggesting the church should lose its tax-exempt status for Jeffress’ involvement in politics. Lynn has never met Jeffress. But when I talked to Lynn on the phone, he sounded exhausted at the mere mention of his name.

When the issue comes up in a sermon, Jeffress often refers to Lynn as “my friend Barry Lynn.” He never fails to point out that a Baptist coined the phrase “separation of church and state.” And that no church in American history has lost its tax-exempt status for anything a preacher said in the pulpit.

Jeffress regularly tells other pastors to endorse political candidates from the pulpit if they feel so inspired by God. He stops short of endorsing anyone from the pulpit himself, though, noting that his endorsement of Rick Perry was simply his personal opinion—of course, he’d like to see “a competent Christian” in the White House. First Baptist Dallas has always been the church of some of the most powerful Texans, from historic business icons like H.L. Hunt to active politicians like Tom Leppert. And though his congregation is heavily Republican, he knows there are a few Obama supporters in the crowd. It’s also important to him that he not be thought of as a stereotypical “Teavangelical.”

“Politics can be so divisive,” he says.

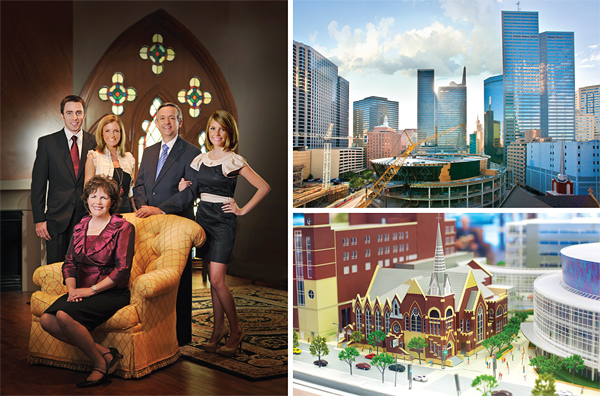

After Robert Jeffress spent 15 years in Wichita Falls, First Baptist Dallas called him home in 2007. The selection process was long, with a committee looking at more than 150 preachers across the country, praying about it constantly. “We knew how epic this decision was,” says Kimberly Byrum, a member of the search committee. “We all knew the church had been in decline for years. We knew with the wrong decision, the church could die.” One of the first things Jeffress wanted to talk about was building a new sanctuary.

When Jeffress took the job in Dallas, he didn’t get a big raise. The church doesn’t release the salaries of staff members, but he says he is paid in accordance with other Southern Baptist megachurch preachers. Any revenue from books sold through the television and radio ministries, or through the church bookstore, go to the church. He keeps the rest, though he stresses that amount is “minimal.” He and Amy have a large house in Far North Dallas, and they enjoy family vacations, but, he says, his has always been a family of ideas, not material possessions.

Since he’s been back in Dallas, both membership and attendance at the church have gone up. It has received pledges for nearly all of the $128 million needed for the new buildings, and it has more than $86 million in hand. Construction began in the fall of 2010 and should be done by Easter 2013. “This is without a doubt one of the most exciting times in the church’s history,” says John Grable, First Baptist Dallas’ communications minister.

I tagged along with Jeffress on a recent Sunday. Sundays still make the pastor giddy. He’s out the door and into his black Mercury Grand Marquis by 7:45 am. When he arrived at the parking garage across from the church, there were two broad-chested security guards waiting for him. At least one of these men would be within feet of Jeffress for the rest of the day. The church isn’t worried about liberals with guns so much, he says, but there are just so many crazy people out there. “Of course,” Jeffress says with a smile, “so many of our members are packing, if anyone ever did try something, it’d be like the shootout at the OK Corral.”

As upsetting as he may be to some outsiders, the people here love Robert Jeffress. He’s making the arguments they might not have the words to articulate. “He equips us to go out and talk to neighbors and co-workers,” says Matthew Elias, a retired Navy officer who also served on the search committee. “He gives us the information we need to be a match in this dark world.”

Every Sunday he gives a 9:15 sermon, and repeats it at 10:50. There are more than 1,000 people in each service and several hundred more in the contemporary service in the chapel, with a 120-person choir and a 50-person orchestra. That week he began his message with an anecdote from the news, the story of a Baptist youth camp pastor in Arkansas who was arrested after he was caught secretly recording women in the shower with a camera hidden in a pen.

“Ask yourself why these kinds of accounts are not that rare,” he said to the congregation. “How do you explain how a Christian who has heard the calling of God can be led so astray and fall into sin?”

The answer, ultimately, was: “The mind controls our actions and our actions control our destiny.” His advice: “Guard over your mind.”

After his second service, he met with new and prospective members over a buffet of fried chicken and mashed potatoes. Jeffress didn’t eat. He always waits until he gets home, where he makes himself a grilled cheese sandwich—like his mother used to—and watches Meet the Press. Then he usually takes a nap. He’s had the same Sunday afternoon routine since he was a child.

On Sunday nights, he gives a different sermon, usually with a political tone. The most recent series started on the 10th anniversary of 9/11. This week’s message was about how to stay positive knowing that the end of the world is inevitable. It was straight from the last chapter of his new book, Twilight’s Last Gleaming. His conclusions: don’t think in terms of decades; think of all eternity and how you’ll spend it in paradise. And with that in mind, rejoice, but also be productive.

That’s another reason I like Jeffress. He can find a reason to be positive about even the most grim circumstances. “People don’t want to hear doom and gloom,” he told me. “They’ll just turn away. Life is hard enough.”

It’s a fine line to walk, staying optimistic but also lovingly reminding people of the pending Apocalypse. He knows end-of-the-world sermons bring crowds, and he knows it can look like he’s using fear and tragedy as marketing tools, but he really does feel that fear. He reminded me several times in our conversations that his mother died at 56 years old, and that he is now 56 and constantly aware of the brevity of life. And he fears that God will see him if he misbehaves, and that He will punish him. These fears drive him.

But fear is a funny thing. It can make very smart people come to what might otherwise seem like strange conclusions. Sometimes he just disagrees with the vast majority of science, like evolution: “I just don’t understand how matter could evolve itself to contemplate itself.” Sometimes his beliefs seem like they come from science fiction, like a chapter of his new book that deals with persecution. He describes an Antichrist-led dystopian future in which everyone is implanted with radio frequency identification chips, and Christians are forced to line up for food, hoping the technology will miraculously fail to notice they are missing the mark of the beast.

“Such a terrifying future is not just a possibility,” Jeffress writes. “It is a certainty.”

Over three weeks, I met with Jeffress several times. After following him through his day at church, I watched him as he shot a segment for FOX News. As always, he was prepared and polite, and very confident.

After his segment wrapped, we went back to his office at the church. He knew my deadline was fast approaching, so he asked if I knew what direction I was going with the story. Until then, he’d asked what I might write only once, and then all he said was, “Now, Michael, is this going to be a positive story or a negative story?” So he asked partly because he was nervous. (He wasn’t as nervous as Amy, though, who showed up to our interview with four pages of handwritten notes she’d prepared, mostly about his family history. Then she asked me not to talk to their two daughters, Julia, 23, and Dorothy, 19.) But Jeffress also asked me because he knew I was nervous about my deadline, nervous about what all the nice people at the church would think of the article.

I mentioned to him that I had spoken with Mel White, the man who wrote Dr. Criswell’s autobiography. (He did the same for Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, and Billy Graham.) In 1994, White announced to the world that he is gay.

Jeffress said he’d heard of White, but that they’d never met or spoken. I told Jeffress that White says that when pastors like Jeffress tell

people that gay is not okay, it fuels discrimination and can drive some gay kids into dangerous depressions. Jeffress reminded me that his, Jeffress’, is the message of hope—that homosexuals can change through the power of Christ. He generally equates being gay with alcoholism or a genetic proclivity toward violence. He always points out that no one sin is any worse than the others.

That’s when I asked him about his own sins.

“What are you guilty of?” I asked.

Jeffress sat in silence for nine and a half seconds.

“I’m not pausing because I can’t think of any,” he finally said, smiling. “I just can’t think of any I want to tell you.”

Sometimes life is a puzzle, or a game like Card Sharks. Sometimes it’s about figuring out the right keys to push to get the reaction you want, like on a piano or an accordion. Sometimes it’s figuring out the right things to say.

At some point that afternoon, we came to the topic of doubt. I told him I refused to believe that a man so well-read and well-traveled could go his whole life without having any doubts about the existence of God or an afterlife.

“It’s not true that I’ve never had doubt,” he said. “I did have doubts once.”

I perked up.

He said he’s never doubted the existence of God or Heaven or Hell. He’s never doubted that Jesus was his savior or that he was called to be a minister. But there was a time when he was a freshman at Baylor that he had a very liberal religion professor. The professor used to explain to the class that the Bible is filled with contradictions, that much of it is metaphor, just the best explanations people had thousands of years ago.

Jeffress had never before had any reason to doubt anything a teacher had ever told him. He told me he stopped reading the Bible so much. He lost his interest in bringing people to Christ. Over the next few months, the doubt grew. During Christmas break, he went to a mission conference where Billy Graham was talking. That night, Graham confessed to the crowd that there had been a time once when he doubted the inerrancy of the Bible. He said he found clarity on a golf course in Florida one day, knelt down on the spot, apologized to God, and decided he would never doubt the Bible again.

He told me that as he sat listening to the story, Jeffress felt like God had brought him there that night, brought him to hear this exact message. He decided right then and there that he would never doubt again. He even had Billy Graham sign and date his notebook that night.

Aside from that, though, he stressed, no doubts.

I pointed out that this means he views the world the same way he did when he was 5. And that my views on just about everything have changed since then.

He told me he doesn’t see the world in just black and white. But then he explained that through 56 years, he’s boiled it all down to this: “Either it’s all true or none of it’s true.”

And the chances that none of it is true, that there’s no God, no afterlife, nothing guiding the universe aside from chaos? “In my mind, zero chance.”

This is perhaps what I like most about Robert Jeffress. He says what he believes, even when he knows people will think he’s a hate-filled moron. He’s bold, but his conclusions are not without thought or contemplation. He isn’t motivated by hate. He’s just saying what he knows to be true, and in a free society we can’t ask for much more than that.

I realized after spending time with him that in so many ways, I’m envious of Robert Jeffress. I would love to have that courage. Such a large part of success in any aspect of life is simply believing. I’m riddled with doubt—so much so that I had to rewrite this story because I wasn’t certain what I thought about Jeffress and what I wanted to say.

But, in some ways, I also feel sorry for Jeffress. Yes, the world is easier if you believe certain things, but that’s also a life spent in fear, a life dedicated to not changing.

Of course, that’s not how he sees it. “If I’m wrong, what have I lost?” he explained. “I’ve lived a happy, healthy, purposeful life. If an atheist is wrong, it costs him his soul.”

When I finally turned my recorder off, as we sat in his office, he said he had a question for me. He looked me in the eye.

“So, Michael, how do you feel about all of this?” His voice was soft, curious. “What do you believe?”

I hesitated. Honestly, I had been dreading this question. What do you say to a man who has dedicated his whole life to believing, a man who has been proselytizing for more than 40 years? I’d grown to like Robert Jeffress. I didn’t want to disappoint him.

“Well,” I said. “I’m not nearly as certain as you.”

Write to [email protected].