Artist Andrew Underwood had tried his luck with Dallas’ commercial galleries, meeting with gallerists and opening his studio to visits. Their interest in his work remained elusive.

“I felt like there was no place for me in a commercial gallery in Dallas,” says Underwood, whose “research-based” art projects often combine drawings and multimedia, books, boxes, songs, maps, and photographs. “The response I kept getting was, ‘I can’t do anything with this.’ ”

What followed was a three-step descent into discontent: a trip to New York to see a well-curated show by Thomas Demand at Matthew Marks Gallery, a panel discussion at the Dallas Museum of Art focused on local art, and a subsequent article on the arts website Glasstire written by Lucia Simek that spawned a long chain of comments parsing the various shortcomings of the Dallas “scene.” (Full disclosure, Simek is also my wife and a D Home contributing editor.)

“I was thinking about adding my two cents,” Underwood says of the Glasstire comment kvetching. “But what I needed to do was take action rather than just talk.”

Underwood reached out to Simek; Ryder Richards, an artist, prolific curator, and Richland College art professor; and Joshua Goode, an installation-based artist who teaches and runs a gallery at Tarrant County College-South and mostly shows outside of North Texas. (More disclosure: both Richards and Goode contribute to D Magazine’s arts and entertainment website, FrontRow.) The quartet met at a Central Market cafe and began hashing out a plan, a project that could, in whatever small and accessible way, move the needle.

“The idea was, how do we do things that commercial galleries aren’t doing, things that add to the Dallas art scene?” Underwood says. “But everything happened much faster, much bigger, and much better than I expected.”

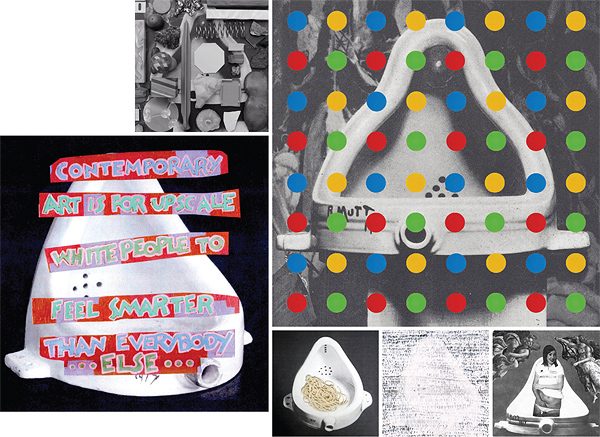

The group adopted deliberately tongue-in-check formality, calling itself The Art Foundation, and gave birth to an idea as simple as it was ingenious: an homage to one of the seminal works of modern sculpture, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, the plain urinal that the artist famously declared art and submitted to the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in 1917.

Except the history of Fountain is more complicated than that. Duchamp replicated the piece four times, deepening the complexity of the work. If Fountain is not the actual urinal first exhibited by Duchamp, but rather the idea of placing a urinal in a gallery, what does that say about the nature of the art object?

That question sparked The Art Foundation’s project, entitled Fountainhead, which makes a connection between Duchamp’s work and the way digital technology has spurred the multiplication and diffusion of images. The group gathered photographs of four renditions of Duchamp’s Fountains and emailed them to artists, some local, some as far off as Paris and Berlin. Participants were asked to manipulate the images, to appropriate them, to, in a sense, Duchamp the Duchamp. The submissions were then collected and bound in an umbrella-size book, printed and stitched together by the bookmaker Underwood. For two days in April, Fountainhead ran concurrently at a loft space owned by The Gibson Company near Fair Park during the same weekend as the Dallas Art Fair.

There were plenty of spin-off art events taking place around this year’s Art Fair, and though 100 or so people attended Fountainhead’s opening, it was largely lost amid the hubbub. But one person who did see the book was Jeremy Strick, director of the Nasher Sculpture Center, and he was impressed. He had chief curator Jed Morse and adjunct assistant curator Catherine Craft (a Duchamp scholar) see it, too. What was the plan for the book after the exhibition ended, they asked? The Art Foundation didn’t know. The Nasher did. They wanted it.

“It was an impressive object,” Morse says. “It was very different and very well done, the quality of the manufacturing of the prints, the binding, and the cloth covering. The book is enormous. But we were also pleasantly surprised by how thoughtful and coherent each of the individual works were, and how coherent it seemed as a single work of art.”

Collecting Texas art isn’t the focus of the Nasher. While the museum has accepted a few works of art donated by Texas artists, Fountainhead was a different kind of acquisition, not a work by an established artist but a collaborative, grass-roots project put together with the intent of raising the local bar on art.

The plan for Fountainhead now is to exhibit it at the Nasher, accompanying a show that opens September 29 called “Sculpture in So Many Words, Text Pieces 1960–1975,” which consists of conceptual work that, like Fountainhead, also deals with the nature of the art object.

“Fountainhead seemed like a perfect complement for this particular project primarily because Duchamp’s Fountain serves as the progenitor of a lot of the more conceptual considerations of the art object,” Morse says. “And so having the Fountainhead book to show helps bring it to the present.”

Those commercial galleries that ignored Underwood? The Nasher, it seems, owes them a debt of gratitude.