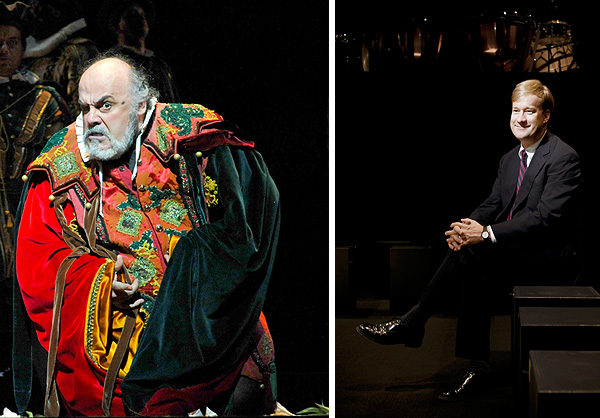

Apart from the Janacek cancellation, The Dallas Opera has announced some intriguing programming for 2011-12. In collaboration with the Dallas Theater Center, across the street at the Wyly Theatre, the company will mount three performances of Peter Maxwell Davies’ chamber opera The Lighthouse, a work both musically innovative and fairly short. We’ll also get, next year, the company’s second production (the first was 35 years ago) of Wagner’s revolutionary Tristan und Isolde, but now only semistaged. Not much actually happens in Wagner, anyway, at least for the eye; the lovers and other characters in Tristan spend a lot of their time just standing onstage, bemoaning their fates. The Dallas Opera has re-engaged Elaine McCarthy, who did the brilliant computer-generated projections for the world premiere of Jake Heggie’s Moby-Dick last year. Light staging and projections—“light” in two senses—will cost less than renting costumes and sets.

One thing Cerny doesn’t want opera to be is “fussy.” Going after students, young people, new audiences is all well and good. But the advertising that the marketing gurus have generated might astound and annoy even someone lacking old fogey status. In print, we see this for next season: “Lucia di Lammermoor: Dead Men DO Wear Plaid.” And “La Traviata: Let’s Party Like It’s 1849!” And on the radio, you may recall the far from fetching interchange last March advertising Rigoletto: “It’s about a jester”; “Surely, you jest”; “Don’t call me Shirley.” Fort Worth Opera is even worse, with so-called “real” conversations between timid, scared first-time opera-goers who need reassurance that everything will be all right. I am not a stuffy fuddy-duddy, but these people sound—not to put too fine a word on it—imbecilic.

My question to Cerny: aren’t these radio spots demeaning and condescending, not just to the art form but to the potential audiences who are being insulted as crude and barbaric by the very group trying to woo them? He said that even in San Francisco, the supposedly more sophisticated city on the hill, similar ads produced positive results. The public loved them. Go figure. I guess people like being talked down to; it calms their nerves rather than insults their intelligence.

Of all the arts, opera is the costliest because it is the most collaborative. Demographically, its audiences are older than those at the symphony. Audiences for dance, even ballet, are younger still. One understands why: dance gives you bodies in motion. It’s sex onstage. And neither dance nor orchestral music threatens to take as much of your time as an evening of “Grand” (horrible adjective) Opera. The businessmen, creative people, and the patrons who hold the purse strings must work together to keep what was a lively popular form in the 19th century, the age of most operatic masterpieces, alive. If ads that seem vulgar to an academic like me will do the trick, I’ll be happy to reap the benefit of their success. If ramping up revenues requires dumbing down advertising, so be it.

Whatever works, works. In arts organizations, what has worked best and most, until now, is longevity. And this presents a real problem today. The late Peter Marzio directed the Houston Museum of Fine Arts for nearly 30 years. He built up relations with local donors; he increased the stature of a great museum. Ditto David Gockley, who turned the Houston Grand Opera into an internationally acclaimed company, famous for new commissions and premieres, during his even longer tenure, until 2005, when he left for San Francisco. Going farther afield, we find the conductor James Levine, however faltering, in his 40th year at the Metropolitan Opera. Philippe de Montebello held the reins at the Metropolitan Museum for three decades.

No Dallas arts organization has had the good luck or the luxury of such lengthy directorship. Keith Cerny won’t stay here for 30 years. The question is: can he, and other arts leaders, work their miracles in shorter time spans? One of Cerny’s fans is Arlene Dayton, a major arts patron who has worked for just about every organization in town. She calls Cerny “knowledgeable in music, management, and finance, a strategic thinker with ideas and plans about how this opera company should look in the 21st century.” She is playing her cards close to her vest. Major musical organizations across the country—the estimable Philadelphia Orchestra and George Steel’s New York City Opera most prominently—are beginning to totter or sink. Some will disappear. Cerny and The Dallas Opera will succeed if they deliver the kind of product, and nurture the kinds of audiences, they want and need. And if they can do this while also living within their fiscal means, then they will have made an important statement about the artistic value of economic prudence.

Write to [email protected].