“I stood there and thought, ‘What can I do?’ ” she says. “I can handle things if I have focus and goals. I can’t just sit here and focus on myself.”

The next morning she called her state representative, Allen Vaught. “I was like, ‘Screw this. I will not rest until women are told [about dense breast tissue],’ ” Salmeron says. “Because when you are told information like this, then you can take action, then you can decide. If you know your grandfather and aunt and uncle had heart disease, you are going to do something about your heart. But if you don’t know anything, you can’t advocate for yourself.”

Perhaps no one in the legislature was better equipped for the case than Vaught. A Democrat, he knew his way around cancer and cancer legislation after spending years representing asbestos victims who had contracted mesothelioma or lung cancer. After hearing Salmeron’s story, he thought about his wife and children, the children who wouldn’t have a mother if she died because dense breast tissue hid a tumor.

He was onboard.

While Salmeron was heading toward a lumpectomy to remove the 4-centimeter growth, Vaught hit the road, speaking with doctors at UT Southwestern, Baylor Medical Center, the Paul L. Foster School of Medicine in El Paso, and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, looking for their support. His goal was to introduce legislation that would require FDA-approved mammogram facilities to inform women with dense breast tissue of the limitations of their mammogram results.

The same day that Salmeron was going under the knife, Connecticut became the first state to pass legislation regarding dense breast tissue. Vaught and Salmeron tinkered with the wording for Texas, after deciding the Connecticut bill as it stood wouldn’t work here.

As Salmeron jumped from surgery to radiation to surgery throughout the summer and fall of 2009, Vaught was drumming up support for the legislation. The American Cancer Society supported the bill, but didn’t push it, while the medical community was wary of government intervention, but eventually ceded. From the summer of 2009 to the fall of 2010, it made slow but sure progress to becoming a law.

Then Vaught lost re-election.

“I thought it was going to die,” Vaught says. Instead, it flourished. Yes, there were moments when it looked like the bill wouldn’t pass, but Salmeron wouldn’t stop. The same tenacity that led her to White Rock Lake, the same tenacity that forced her doctor to perform a sonogram instead of just another mammogram, that tenacity kept the bill alive.

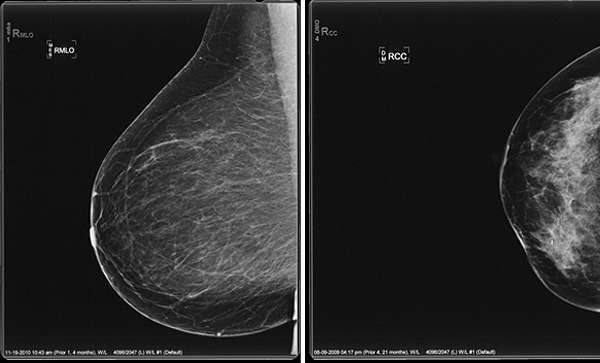

Vaught’s legislative director, Jo Cassandra Cuevas, moved on to Rep. Ana Hernandez Luna’s office, taking the bill with her. Salmeron’s weeks quickly devolved into a series of Austin road trips. At 7 am, she’d get a call from Hernandez Luna’s office asking if she could testify that day. Salmeron would throw on some clothes—“It was always something pink”—and drive the 200 miles from Lakewood to the State House. Before and after she testified, she’d roam the halls, handing out pink folders with the bill, her tumor-hiding mammogram, and breast cancer facts tucked inside. Each letter was signed, “Thank You, Henda,” in fuchsia handwriting.

As the bill worked its way through the House and Senate, its name, Henda’s Law, became known. People recognized Salmeron in the cafeteria and hallways. She talked to aides, directors, parking attendants. It didn’t matter. If she actually grabbed the ear of a representative or senator, it was a coup. From its March 3, 2011, filing date through the end of the 82nd Texas Legislature in June, the bill was formally discussed, motioned, passed, or debated 60 times. The number of informal debates in the cafeteria is unknown.

The House passed the bill 136 to 5, with two absences. The Senate vote was unanimous. In October 2009, Henda Salmeron had her last radiation treatment for breast cancer. By June 2011, she had a law named after her.

“The person who got that passed wasn’t any legislator, it was Henda,” Vaught says. “That woman was down there nonstop, reminding people that if it’s going to pass it’s going to save some child’s mom or some person’s wife.”

As we sit in Salmeron’s kitchen, she slides off a black wedge to show me her battle scars. She’s just returned from a trip to the Rockies. As a participant in the TransRockies run, she ran 120 miles over the course of six days, and her feet are still bleeding.

Since her radiation treatments ended in 2009, Salmeron set her sights on her latest endeavor: ultramarathons. The surgeries affected her rowing, so she switched gears, traded in the water for the road, and started running. Her first endurance race, in 2010, was the Himalaya 100, as in “sunrise over Mount Everest” Himalaya. In backward fashion, she’ll tackle her first marathon, the New York Marathon, this month. She’s lost an additional 15 pounds from her new hobby.

As we’re sitting, I bring up the fact that in less than eight hours her bill will become law. She pauses for a second, does the math, realizes I am right, and chuckles. The week before, she had lunch with a few doctors and administrators at UT Southwestern. She had achieved the ultimate, 21st-century definition of fame, they said: she had become a verb.

“In radiology circles we’re saying, ‘Have you Henda-ed your center yet?’ ” she says, nonplussed that she’s joined the ranks of Google and Facebook. “I said to him ‘It’s time. It’s time to have dense breast tissue on the table. It’s time that women know.’ ”

Write [email protected].

Learn More

Salmeron is working with women on a national level to pass federal legislation informing women of the risks associated with dense breast tissue. For more information, visit hendaslaw.com.