Eisenhower may have forbidden the kind of premeditated plundering the Nazis did, but the GIs who liberated Europe were still soldiers, and, like soldiers since time immemorial, they did their share of looting. Usually, it was items from people’s homes: silverware, jewelry, gold watches, antiques, old books. “Considering what the soldiers had been through, you could hardly blame them, and most of what they looted was innocuous enough,” Edsel says. But sometimes what was taken was much more precious. Probably the most famous case of this involved a sometime Dallas resident named First Lieutenant Joe Tom Meador.

Meador could have been a Monuments Man himself. He’d majored in art at North Texas State University. He was a country boy, from Whitewright, a small town near Denison, and, like one famous Monuments Man (Lincoln Kirstein, the future ballet impresario), Meador was gay. Being a forward artillery observer, he was unquestionably brave, but he was also an inveterate looter whose arts background guided his sticky hands. And his job as a forward artillery observer gave him plenty of opportunities during that ambiguous period between the German retreat and the American advance.

The treasures were now hidden in a nearby mushroom cave for safekeeping. Officials from the church asked the Americans to post a guard detail outside the cave. This the American soldiers did. Unfortunately, the guard detail was headed by Meador, who promptly stole about a dozen objects, including: an illuminated gospel book from the 9th century, an ivory liturgical comb, a printed evangeliary, and jeweled reliquaries. When they found out what had happened, the church authorities complained. For a while, the U.S. Army did investigate the case, but when borders were redrawn and Quedlinburg became part of the Russian Zone, the Army lost interest in the matter.

Following his discharge from the Army, Meador returned to North Texas. For the next 35 years, Meador lived a double life, spending his weeks dressed in overalls and cap, helping run the family hardware store in Whitewright, then driving down to Dallas for weekends among the gay community. Though he apparently sold many of the objects he’d stolen to help finance his lifestyle, the medieval treasures he kept, sometimes showing them to guys he wanted to have sex with. Despite this, no word of the treasures got out until after his death in 1980.

The treasures passed on to his brother, Jack Meador of Whitewright, and his sister, Jane Meador Cook of Mesquite. Once they learned what they had, they got greedy. For years, a wary courtship went on between the Meadors and several potential buyers. By then, the West German government had gotten wind of it and started investigating.

The Meadors eventually sold the objects to the West Germany government for approximately $2.75 million, but that was only a tiny fraction of what they were worth, and the brother and sister spent the next 10 years being prosecuted and harassed by various agencies of the United States government, especially the IRS, which sought more than $50 million in taxes, penalties, and interest. The Meadors settled with the IRS in 2000, but both died a few years later. Whatever they made couldn’t have been worth what it took out of their lives.

Two pieces remain missing from the Quedlinburg treasures: the crystal reliquary looking like a bishop’s hat and the hollow gold cross. Attorney Thomas R. Kline, who 20 years ago represented the Quedlinburg church in the case, thinks they’re still in the Dallas area. Now a litigation partner at the Washington, D.C., office of the Houston-based law firm Andrews Kurth, Kline recalls how for a while he kept getting phone calls and faxes, mostly from antiques dealers who thought they might know about the missing objects. But one call stands out.

“My partner Alan Harris got a call from some woman asking about the cross,” Kline says. “She asked Alan to describe it to her. She listened for a while and then very quickly said. ‘Oh, mine’s much nicer than that,’ and hung up. I’ve got a funny suspicion that she had it. She probably still does.”

“We took back a stolen item to Berlin in May that an American soldier had picked up as a souvenir. He had no idea what it was. It turned out to be a very important document.”

The document was Gemäldegalerie Linz Album XIII, a catalogue of paintings by 19th-century German artists that Hitler planned to put in his museum. Essentially, it was a shopping list.

The task of confiscating most of the artwork went to Alfred Rosenberg. His “action teams”—the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, or ERRs—found and took whatever paintings Hitler wanted. But Rosenberg had competition in Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe. Göring helped himself to whatever was on the walls of art museums and confiscated private collections of wealthy Jewish families. Though he wasn’t supposed to take the artwork Hitler wanted, he sometimes did, just so he could personally hand them over to Hitler. Because Göring was much more powerful than Rosenberg, it wasn’t long before the ERRs were working for him.

In a last-ditch effort to ingratiate himself, Rosenberg prepared a series of beautifully bound catalogues containing photographs and detailed descriptions of the paintings going to the Gemäldegalerie Linz.

“Rosenberg brought all these books to Hitler as a way of saying, Look how good I did,” Edsel says. “But by then Hitler didn’t want to see him anymore. On the other hand, Hitler did love the books and, as we learned much later, took them with him wherever he went.”

Which brings us back to the American soldier.

John Pistone—the man who’d taken the 12-pound, leather-bound book—was then a young infantry private whose unit had just taken over Hitler’s ransacked house near Berchtesgaden. There were other volumes of the collection lying around (the original collection included 31 albums), but one was all Pistone had room for in his pack. For the next 64 years, it stood on his bookshelf in his home in Ohio. Sometimes he looked at it, but he didn’t really have any idea what it represented until a friend looked it up on the internet. Pistone also learned about Robert Edsel and the Monuments Men Foundation. He decided to give Edsel a call.

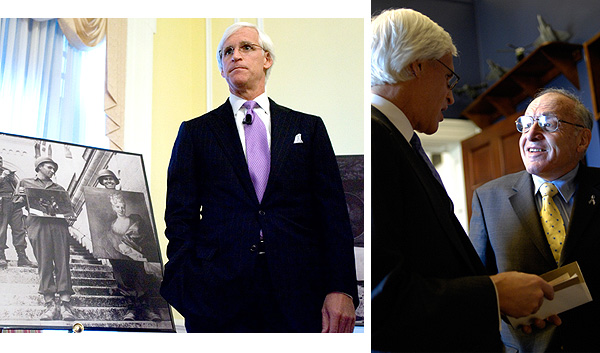

“Until he called me, everyone had assumed they had been destroyed when Hitler and his staff evacuated from the Wolfsschanze in East Prussia in 1944, because that was their last known location. But it turns out that Hitler had prized those volumes so much he took them with him back to Berchtesgaden,” Edsel says. “When I first met Mr. Pistone, I encouraged him to be a visible presence in the return of this document, to allow him to receive the credit he was due, but also to set the example for others. He graciously agreed. It was a very happy moment to witness this fine veteran receive such praise in the presence of his family. He later told me it was one of the proudest moments of his life, and it speaks volumes about what we at the foundation are all about.”

Album XIII has a new home now, at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin. But where are the other volumes? “Millions of items are still missing,” Edsel says. “Now that the World War II generation is leaving us, we can expect a deluge of items to start surfacing. A lot of the veterans who still have these things should think about how much good they can do by saying, ‘I’m done with it. Here it is!’ ”

Brendan McNally is the author of Germania (Simon & Schuster, 2009). Write to [email protected].