He stuck with that story until he flunked a polygraph. When he broke down and confessed, he described how he’d beaten and kicked the child when the child wouldn’t stop crying. He even imitated the high-pitched voice the toddler used as he called for his mother. “He was mocking him,” Fort Worth police detective Renee Kamper testified years later. “I’ll probably never forget it.” There were also wounds on the child’s tongue that a doctor testified were consistent with burns from a match or cigarette.

“Randy would never confess to that part, the torture,” Shook says.

Facing the prospect of an even longer sentence from jurors not likely to sympathize with a child abuser, Randy pleaded guilty to felony injury to a child in return for a 30-year prison term.

Crystal seems uncomfortable with the details of the crime when it comes up in the couple’s rambling phone calls. Walking down memory lane with a convict, she is learning, can be a scary trip. Most wives, when they learn something about their husband’s past, don’t have to confront the idea that he burned a toddler’s mouth with a cigarette and broke the child’s arms and legs.

The babysitting, he tells her on the San Antonio trip, was a good deal for him. “I had a rule,” he says. “I wouldn’t babysit high. I told them, ‘Let me know ahead of time,’ so I wouldn’t do anything.” It didn’t always work out that way, he tells his wife, and on the night of the beating he says he was high on LSD.

Crystal, who had recently heard someone describe Randy as “someone who breaks the arms and legs and skull of a baby,” apparently had never heard all the details of the crime.

“What are they talking about?” she asks.

“It wasn’t a bad thing. It was a hairline,” Randy says. Silence comes from the other end of the line. “Crys?”

“Mmm-hmm,” she says, then more silence.

“Hello?”

“I’m here.”

“What’s wrong?” Randy asks. “It was a toddler. Very soft heads. It was a horrible thing, babe. It’s hard for me to imagine doing it. There’s no way. I still ask myself why, you know—I don’t know what to say, but I’m sorry. I think back on it. I don’t know why.”

She goes silent again.

“Babe?”

No response.

“I’m sorry about all this,” he tells her.

“I know you are,” Crystal says as she changes the subject back to the driving trip. “I’m behind a big yellow bus.”

Before he lets it go, Randy tells her that he’s really good with children. “You know how some people are just natural with children? That’s me.”

After just a few minutes of discomfort, they are back to small talk and professions of love. They exchange “I love you”s at the end of nearly every 15-minute call, so often that Crystal starts to joke about their “soap-opera moments.”

“Honey, I just want to look at you. I don’t have to eat,” she says, in a soap-star voice.

Randy says, “Do you realize that the world goes ’round, but my heart is always right there, in one place, with you?”

Sometimes, Randy did both tasks. He drew Mark Burgess, a maintenance supervisor, into a place where Rivas could hit him on the back of the head and knock him out. Randy then removed Burgess’ clothes, bound his hands and feet with tie straps and duct tape, placed a gag in his mouth and duct tape over his eyes. “You think I like you, but I hate your ass. Give us any problems and I swear I’ll kill you,” Burgess quoted Randy saying during the trial.

Randy was just as bold in a note he left in his cell. “You haven’t heard the last of us,” it read. The words were more chilling in the wake of Hawkins’ killing. And they didn’t help Randy’s trial defense, which portrayed him not as an aggressive killer but as a passive sort, a bystander who chiefly followed along.

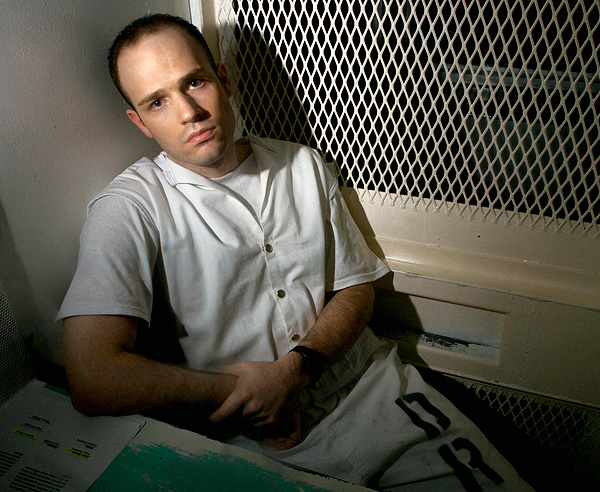

Of the six escapees who went to trial, all of whom received the death penalty, only two testified: ringleader Rivas and Randy. “His ego is huge,” says Shook, who cross-examined Randy over two days.

Randy testified that he joined the escape because prison was so isolating. He received no visitors and only a few letters from his brother. The rest of his testimony was a series of denials. He said he never hit anybody during the escape, refused to take part in the gang’s South Texas robberies, and only carried a gun during the Irving store robbery because the gang “made it very clear it was their way or the highway.” He told jurors he never fired a shot.

“Randy’s own testimony placed him beside Hawkins’ car, on the passenger side, and we showed shots were fired from that position,” Shook says. Additionally, Randy had been shot in the foot, evidence that he was around the gunfire at the back of the store. More importantly, Shook says, all the defendants were tried as parties to the murder, guilty under the law because they knew their actions as part of the group would lead to the killing. “Five guns were used,” Shook says. “We never could trace back who held each gun.”

Nearly a decade later, in recalling his arrest on the phone with Crystal, Randy offers his wife this explanation for why he surrendered to police: “I can’t hurt anyone and I can’t kill myself.” He came out of the Colorado mobile home, which was surrounded by cops, with his hands up.

“Did they know you were coming out?” Crystal asks.

“No, they didn’t,” he says.

“Oh, my,” Crystal says in a little kitten voice.

“I just put my arms in the air, said I’m unarmed.”

“Oh, Randy,” she coos. “During that extradition hearing, you looked so scared in that video.” She says, “I’m someone who could have kept you safe. I could have. I never would have imagined you getting found guilty for not killing someone.”

“I love you, honey,” he says.

“I love you, too.”

Crystal might have provided Randy virtual Texas tours, money on his “jail book” (good for food and magazines), a sympathetic ear, and regular phone sex, but she wanted to do more. “I want to get you a ring,” she tells him during one call in late August 2010.

Randy tells her the gift might be against prison rules, then suggests she “call your friend” for permission. That person turns out to be the Polunsky Unit’s senior warden, Timothy Simmons.

Crystal has Simmons’ cell phone number. He answers it even when he’s in meetings. “There’s a bunch of calls to him,” says Dallas County First Assistant District Attorney Terri Moore. Crystal’s calls to the warden and Randy’s description of his time in Dallas put Moore’s office on alert to some possible security lapses surrounding Randy. They were appalled that a high-risk inmate and former escapee would be permitted to gab on the telephone for hours on end.

“He’s very personable, and she’s pretty and she’s using all her skills,” Moore says. “The next thing you know, they just suck these people in, and they let go of all their security. They forget what he did when he escaped last time.”

The prosecutor’s concerns led to two bailiffs in state District Judge Rick Magnis’ court being reassigned while a review was made, and security was heightened at Randy’s third hearing in Dallas. Somehow, talk of security concerns gave some around the case—including Randy’s lawyers—the mistaken impression that he was, in fact, planning an escape.

At the second hearing, Bruce Anton, one of Randy’s appeals lawyers, took Crystal aside and told her their recorded phone calls, web journals, Facebook page, and everything else were making his job very difficult.

“You want me to stop loving him?” she asked Anton. She relayed the conversation to Randy that night on the phone. “He said, ‘You want to love him. You want him dead or you want him alive?’ ”

Prosecutors had used Randy’s words to poke holes in testimony at a 2008 appeals hearing. Randy wrote afterward that he needed to stop posting his journals out of respect for “those who are fighting for me.” But he started back up a year later.

Anton and Randy’s other defense lawyer, Gary Udashen, declined to talk about the case with their six-year-long appeal still pending in a Dallas court.

Moore, who has been a defense attorney as well as a prosecutor, says it’s frustrating for a lawyer to contend with the added variable of a defendant, or a wife, who might not realize all the ways their words can slip them up. “The attorney’s trying to save the guy’s life, and they’re just trying to have a life—for a short period of time.”

On October 6, in the middle of one of Crystal’s virtual phone trips to a fishing spot, guards told Randy to hang up the phone. They moved him to another cell, and then, under heavy security, the next morning they put him in a police car for the trip back to prison. “I noted a billion deputies around and a sniper gun trained on me,” he wrote in an early October journal entry. “We were driving so fast that I couldn’t take the scenery in like on the trip to Dallas.”

Within two months, Randy and Crystal took down that journal entry along with years of material, their wedding photos, and various other content from randyhalprin.com.

But Randy didn’t take the site down. He returned there this spring with a new cause. It’s an online petition to give phone privileges to the 315 prisoners currently held under death sentences in Texas. The first signature came from Crystal, who wrote, “These men on death row are humans and are loved.”

Write to [email protected].