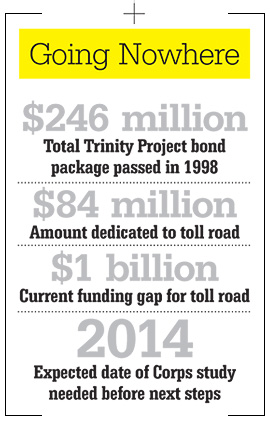

In the fall of 2007, when Dallas residents voted down a referendum that would have killed a proposed toll road built into one of the levees along the Trinity River, the future looked bright. This toll road, our city’s leaders assured us, would solve downtown Dallas’ traffic problems while simultaneously providing much-needed funds to complete the massive Trinity River Corridor Project. One of the most ambitious public undertakings in this country’s history, the proposed project already included plans to reroute the river, assemble three giant bridges, create two lakes, and build the largest urban park in the United States, replete with nature trails and ballparks and delightful views of the city. This toll road would require an equally ambitious feat of engineering. And, we were told, our people were up to the challenge.

Earlier this summer, after a two-year open-records fight led by the Dallas Morning News, we learned that even back in 2007 the Army Corps of Engineers was far from convinced that the toll road would ever work. Just as the weather changes and winds reverse direction, so now, too, support for the toll road is fading. In a story that ran in the New York Times, a Texas Tribune writer recently referred to the toll road portion of the project as “all but dead.” But former mayor Tom Leppert, who is now running for U.S. Senate, still believes in the toll road he championed four years ago, and he insists he did not mislead the public before the crucial vote.

It’s hard to imagine anyone taking Leppert’s word on this, but city officials are pushing forward, literally drafting a supplement to a supplement to the toll road’s environmental impact statement, which itself has already cost taxpayers millions. “The work is continuing,” says assistant city manager Jill Jordan. “It’s just slow because the Corps has to get their work done. We can’t finish our work until they finish their work.”

The saga of city government. This is a lull in the conversation, to say the least. So let’s use this moment as an opportunity to reevaluate. Or, to be blunt, let’s scrap the toll road.

The bad news: we’ve already wasted millions and spent years toiling unproductively on what was, looking back, a bad idea. “It has become abundantly clear over the last decade that the toll road aspect of this project has stalled out the other aspects,” says Dallas City Council member Angela Hunt, who got the signatures needed to call that 2007 referendum. Hunt has been right all along when it comes to the toll road.

Today, there are (at least) four reasons why the road ought to be abandoned. First, it’s now clear that the Trinity Project doesn’t depend on it. D Magazine endorsed the road in 2007 because city leaders insisted that it was integral to the larger project. Flood control, parks, transportation—those were the three legs of the stool. Without the money for the road and the dirt needed to build it, we couldn’t afford to dig the beautiful lakes. Hunt has demonstrated that that simply isn’t true. While the flood control measures and the parks themselves might cost more without the road, that cost will be far less than if it were built.

Third, it’s also clear that the Army Corps of Engineers is not going to approve building a toll road in the middle of a floodplain. Not after the disasters of Katrina and the floods in Tennessee and North Dakota. “The Corps is screaming ‘No!’ at the top of their lungs in the only language they know, which is bureaucrat-ese,” Hunt says. “They said they need to study it. Then they need to analyze it. Then they need to consult. Then they need to study it some more. This is how they say ‘No.’ ”

The fourth reason the road won’t work is probably the most important, though it has been discussed the least. Highways are bad for cities. Inter-city freeways are necessary to link regional economies like Dallas’ and Houston’s and Austin’s. But intra-city highways—the expensive eight- or 10-lane thoroughfares that turn into parking lots twice a day—those choke the life out of metropolitan areas. Even President Eisenhower, the father of the U.S. interstate system, was opposed to putting highways through cities. They displace people as they’re built and then, as time goes on, highways decentralize populations. They make it easier—and often cheaper—to live farther away from the center of economic activity, which means that just as a city undertakes an expensive infrastructure investment, it loses a portion of its tax base. A 2006 study from Brown University found that, on average, each intra-city freeway leads to an 18 percent population loss.

One of the fundamental goals of the Trinity River Project has always been decreasing traffic congestion. Building a highway doesn’t decrease congestion; it makes it worse. Increasing the number of lanes only increases the number of people driving, while decreasing the amount of viable commercial space where a car might be able to get off the road. Modern urbanists now think that building highways is at best a temporary (but very expensive) solution to congestion.

A better answer to Dallas’ traffic problem is to create more transportation options, more ways to get around without a car and better routes to take with one. When San Francisco lost two major freeways after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the city decided that, rather than rebuild, it would replace the freeways with a grid of people-friendly boulevards. Today an area that was once desolate is thriving. With boulevards, a steady, predictable level of congestion actually fuels the local economy. People stop to eat dinner, to shop, to linger in a place that is part of the urban fabric—as opposed to a freeway, which just tears through it. Those places eventually become desirable places to live, which means population density goes up, and the standard of living goes up, too. Forty years ago, people scoffed when Vancouver refused to allow highways through the city. Vancouver today is at least pleasant enough to host the 2010 Winter Olympics.

Scrapping the road won’t speed up the parks and the lakes. Nor will it delay them. And there’s good news: because the original bond involved so many aspects of development, the money that remains can be redirected to other parts of the project. It can be used to get a fresh, 21st-century take on better transportation options.

History will show that the vote to build this toll road was a mistake. An expensive error, sure, but hardly the city’s worst. Now it’s time to move on.

Write to [email protected].