The khakis are a surprise. Rumors have it that he’s now a fashion plate. That he reads Women’s Wear Daily, that he knows what’s on the runways, and that, like a carnival guesser, he can identify the items you’re wearing by label and price, from head to toe.

So when Ray Washburne, the new co-owner, general partner, and president of Highland Park Village, lurches through the door of the ritzy shopping center’s Mi Cocina restaurant, you figure the rumors have it wrong. Because he’s not wearing Zegna or Tom Ford—or, if he is, he’s not wearing them correctly. The outfit he’s chosen on this Tuesday afternoon is straight out of a Casual Friday handbook: brown loafers, khaki pants, a blue and white checkered shirt with a white t-shirt peeking from beneath the collar.

Then again, the garments appear to be quality. Expensive, even. Plus, they fit about as well as can be expected on a man who is 6-foot-5, long-armed, high-waisted, and, at 50, has a burgeoning midriff. And after Washburne folds himself into a booth at the restaurant—one of 15 Mi Cocinas he owns along with his brother Dick and the fruitcake magnate Bob McNutt—he explains that the rumors are, in fact, true. Sort of. Yes, he has read WWD. Yes, he has some concept of what the glitterati are wearing on Rue de Rivoli. But that’s not because he’s interested in fashion. That’s because he’s interested in real estate, the real estate he’s sitting on right now. “We’ve got a very high quality tenant in Highland Park Village,” Washburne says. “And it’s important that we understand the business they’re in.”

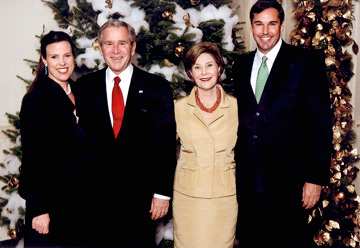

“We,” in the case of Highland Park Village, is Washburne and his wife, Heather Hill Washburne, plus Heather’s sister Elisa Summers and Elisa’s husband, Stephen. The sisters are daughters of Al Hill Jr., who is the son of the late Margaret Hunt Hill, who was the daughter of Lyda Bunker Hunt and the legendary oilionaire H.L. Hunt, at one time the richest man on earth. But you probably knew that already.

Last May, the two Hunt-Hill heiresses and their husbands became only the fourth owners in the 79-year history of Highland Park Village. They bought the property from the descendants of another local business legend, Henry S. Miller. The purchase price: $171 million, or $684 for each of the shopping center’s 250,000 square feet. As far as anyone knows, that’s the highest price ever paid in Dallas for that much retail real estate. Probably it is the highest price ever paid for an existing shopping center anywhere in the Southwest.

The top-dollar sale might never have happened if not for a rabbit-eared Mi Cocina server. “I was having dinner here with my wife one night,” Washburne says between quick sips of an Arnold Palmer. “And one of my waiters had heard someone talking about how they were thinking about buying Highland Park Village. So I happened to see Henry Miller III walking by, and I called him over. He pulls up a chair, puts down a shopping bag, and I say, ‘Are you selling?’

“He said, ‘We’re not promoting it, but we’ve had an offer come to us, and we’ll know in the next couple days if it goes through.’

“So I called him the next morning,” Washburne continues, telling the story in an excited rush. “The deal had dropped. I said, ‘I’ll be in your office in five minutes.’ I hurried over there, we made a handshake deal, and a few months later, the contract went through and I bought it.”

At least that’s how the story goes the first time I hear Washburne tell it. As his friends will tell you, he’s a talker. A fast talker. And a storyteller. It’s a trait that has made him popular on the Park Cities cocktail party circuit. “Ray loves to spin yarn,” says one Washburne associate. Still, sometimes you wonder if Washburne isn’t playing around with details for effect. Because, sure, it’s possible that someone at Mi Cocina was talking too loudly over their chicken con hongos. And, sure, it’s possible that, just like that, two oil heiresses and their husbands agreed to come up with more money than any of them had ever spent on anything before, including Washburne, who has been buying and selling real estate since he got his commercial real estate license at the age of 19. But it seems just as likely that Washburne, a tireless networker, heard from sources closer to the potential transaction that the Millers might be open to an offer. Whichever. Washburne’s “overheard” yarn is certainly more fun to spin.

And fun is something Ray Washburne seems to be having a lot of as he embarks on a multiyear renovation of Highland Park Village. He has changes both dramatic and discreet in mind for the shopping center, alterations he thinks will make the place more inviting than it has ever been and, eventually, more profitable. But even though Washburne is already prettying up the grounds with new landscaping and completely making over the center’s 75-year-old theater, he’s in no hurry to make Highland Park Village’s bottom line more attractive. Which is saying something for a guy who put himself through SMU selling 6-foot-long swaths of carpet to freshman girls and has been hustling for a buck ever since. “This is not a normal real estate deal where you buy something, create value, and sell it,” Washburne says, unfurling himself from the Mi Cocina booth. “This is something I’m creating with the intent of it being in the family for generations, something we’ll leave to our kids and grandkids. So we have time to do this right.

“Come on,” he adds, charging out the restaurant’s front door. “Let’s go look around.”

To understand what’s got Ray Washburne so excited, we need to talk about jewelry. And accounting.

Washburne says he and his family paid a historically high price for Highland Park Village because it is a “gem” that needs “polishing.” Or, sometimes, an “emerald” that needs “shining.” Other times, an “heirloom” that needs “safekeeping.”

The shopping center certainly has been an heirloom for the Henry S. Miller family, which bought it in 1976 for $5 million. Miller was just the third owner of the center, which opened in 1931. Miller convinced luxe brands to set up in the center—bringing Hermès, among others, to a city that was awash in oil money. His changes paid off. Miller’s $5 million purchase price in 1976 roughly translates to $18 million in today’s dollars. That means Highland Park Village has appreciated 850 percent in value during the 36 years between buyers.

This is where the accounting comes in. Highland Park Village has 200,000 square feet of retail space and nearly 50,000 square feet of office space on floors above the stores. When Washburne et al. took over, average retail rents in the center were about $36 a square foot. Washburne wants to quadruple that rate for most of his tenants, to $120 a square foot or more. Put on your green eyeshades and figure the difference: 200,000 x 36 = $72 million annually, whereas 200,000 x 120 = $240 million.

Trouble is, $120 a square foot is about three times more than the highest rate charged by any other shopping center in Dallas. And maybe you’ve noticed that there’s a recession going on. “When we looked at the quality of tenant we have and their sales per square foot, I realized that our competition isn’t in Dallas,” Washburne says, squinting in the sun outside Mi Cocina. “It is not Inwood Village, and it is not Preston Center. Our competition is Worth Avenue in Palm Beach, Rodeo Drive in Los Angeles, Americana Manhasset in Long Island, and SoHo in New York. And, in those places, rents are $150 to $200 a square foot or more.”

A lot more in some places. On Rodeo Drive, for instance, rents range from $200 to $400 per square foot. Yet retail analysts say sales per square foot there aren’t substantially higher than the $1,000 to $1,500 per square foot that Washburne says Highland Park Village’s high-end retailers bring in. Which may explain why the tony shopping center’s most elegant tenants have not balked at Washburne’s rent hikes. “If you went into a high-end steakhouse and they had a $2 entrée, you’d think something was wrong with it,” Washburne says. “We looked at this the same way. Charging a higher rent here makes you more legitimate in the eyes of the retailer. It convinces them that you’re selling them something of real value.”

Well, not everyone is happy. Banana Republic, for one, chose not to renew its lease. Washburne says that decision was voluntary. But consider the chain retailer’s options. Banana Republic occupied 8,000 square feet at the west end of Highland Park Village, making it the biggest retailer on the site. It paid $30 a square foot and faced a quadrupling of that rate—to a rent of nearly $1 million a month. That’s almost 14,000 pairs of straight fit corduroy pants. Banana Republic moved out.

In its wake, Washburne is carving up the store into five separate spaces. Christian Louboutin, Diane von Furstenberg, and Vilebrequin have so far moved in, and a woman’s hair salon is expected to follow next year. All are paying Washburne’s higher rates. But with only a few hundred square feet, Christian Louboutin needs to sell about two pairs of its $900 heels per day to pay rent.

Still, there’s a catch. The Village isn’t just home to Jimmy Choo and Hermès and Harry Winston. It is also home to Tom Thumb and Starbucks and a theater and Deno’s shoe repair. None of those places can afford $120 a square foot any more than Banana Republic can. But Washburne isn’t expecting any more “voluntary” departures, and he’s willing to carve a lot out of his potential bottom line to make sure of that. “We’re going to have loss leaders, but those will also be the things that drive people to come here,” Washburne says.

Take the Village Theatre, for instance. It’s the first thing that the store managers ask about after Washburne sails through the door at the Carolina Herrera store just a few doors down from the theater’s construction site. He is also queried on the subject inside the Village Barber Shop, where little Ray Willets Washburne got his first haircut and where his three young children have gotten theirs. As he crosses the parking lot near Patrizio, someone even shouts at him: “Hey, Ray, when’s that theater going to be done?” “December,” Washburne hollers back in Texas twang. “I’ll send you an invitation, get you a real good seat. Right down front.”

It may be a popular topic of conversation in the shopping center and surrounding neighborhood, but the Village Theatre is an accounting disaster, even with a mezzanine-level restaurant where Top Chef contestant Tre Wilcox will do the cooking. “It won’t bring in a lot of revenue,” Washburne says. “So, if that was the only building I owned in this center, I’d turn it into retail. But because we own everything, we just got rid of four small theaters and we’re going to have two big ones. We’ll have stadium seating and all the latest equipment. If we’re going to have a theater and it is going to be our donation to the neighborhood, we decided we should make it the best theater it can be.

“I can really appreciate this because I grew up here,” he says. “Highland Park Village isn’t just a shopping center; it is a community asset. And we’re going to keep it that way.”