We pretend that art is long while life is short, but it turns out that art—or at least fashions in art—can also be transient. Consider museums. Think of what is on the walls and what is in the basement. Most great museums are icebergs. As much as 90 percent of a collection is hidden underground. Works of art rotate. But once something disappears from view, it seldom returns.

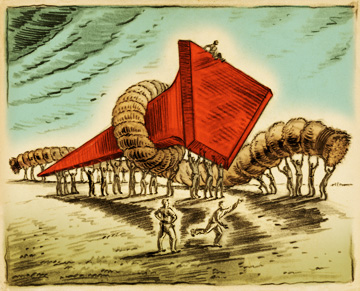

When the new Dallas Museum of Art opened in 1984, one of its main attractions was Stake Hitch, by pop sculptor Claes Oldenburg and his late wife, Coosje van Bruggen. This signature centerpiece went on view in the 45-foot-high barrel vault of Edward Larrabee Barnes’ original building. The work, commissioned by members of the Murchison family, honored the patriarch, the late, legendary John D. Murchison. One printed guide to the DMA lists it as one of the museum’s “10 top treasures.” Like most of Oldenburg’s best works, it made a playful as well as serious statement, in this case about rooting great art in Texas clay. A polyurethane, plastic, and fiberglass rope was tied to an aluminum, steel, and resin hitch, and it reached up—all 150 feet of it—to the ceiling, while the bottom of the bright red stake to which it was tied went into the underground loading dock. It became an instant 5,500-pound icon. For many viewers, especially schoolchildren, it offered the thrill of a seeing a big, contemporary work with an easy “wow” effect.

And then it vanished. After 18 years, Jack Lane, then the director of the DMA, decided that the piece was an obstacle in the barrel vault, and he arranged for its removal in order to make way for the series of temporary exhibitions, as well as social events, that have filled the space since. Oldenburg and van Bruggen received a written assurance from Lane in June 2002: “The board of trustees is committed to reinstall the Stake Hitch again during the remainder of this decade and, once installed, to leave the work in place for at least one year.” An equally polite letter from a DMA lawyer, dated one month earlier, to the artists’ lawyer in New York wiggles a bit in lawyerly prose: “Additional exhibitions of Stake Hitch are likely, but the Museum cannot make a commitment beyond the present decade as to do so would unreasonably obligate the future stewardship of the Museum and successor members of the board of trustees.”

“The remainder of this decade” pretty clearly means “before 2010.” How binding was this promise that has been broken? Does the DMA have a moral, if not a legal, obligation to return the work to public view? The installation of the piece antedated the 1990 federal law that protects site-specific works done afterward. All we know is that the piece lies in storage. A spokesperson for the museum wrote to me with an official pronouncement: the piece “is safely in the Museum’s art storage facility in especially designed and manufactured cradles, and is being responsibly cared for as a valued work of art.” It sounds like cryogenics. Some people—unwilling to be named—have expressed skepticism about the words “safely” and “responsibly.” And the official said nothing about plans for reinstallation. Perhaps the museum folks do not wish to be (ahem) tied down.

We’ll have to wait to see whether Stake Hitch will get a second act in its life. Many people think that for the sake of its mission to preserve art, the DMA should not forget its promise to reinstall the piece. Among other reasons, this is something commissioned by and for the DMA. In addition, there is no other Oldenburg work in Texas that has the symbolic significance and scale of this one. The late Ted Pillsbury, former head of the Kimbell, went so far as to tell me that the displacement of the piece “to accommodate more ephemeral events, be they exhibits [of Sigmar Polke, for example] or parties, bears its own irony, as the sculpture wittily expresses the futility of rooting culture in the barren soil of Texas.”

This may be too strong a protest. Texas has proved itself fertile, not barren, over the past six decades, as art and money (the first as a result of the second) have kept pouring in. Rick Brettell, former DMA director, says that when the Hamon wing was added to the 1984 DMA building, he tried to encourage Ed Barnes to redesign the new atrium so as to receive Stake Hitch in a space designed as a lobby rather than a gallery. This is where most people now enter the museum anyway, having come up from the underground parking lot. A relocation of the sculpture would also have meant that the bottom of the spike, then in the museum’s loading dock and therefore invisible to museum-goers, would have protruded through the floor into the first level of the garage beneath. And it also would have transformed the atrium’s grand staircase and balcony into a viewing platform from which to see the work from above.

But the artists said no, arguing that the sculpture and the architecture of the barrel vault constituted a single artistic experience. They felt that “Stake Hitch has no value except in its original site.” And even were they to be persuaded to move it, they said it would possibly need to be rethought and refabricated, which could cost the museum $1 million. Smart businesspeople, these artists. Brettell says the cost nixed whatever negotiations might have occurred.

Stake Hitch is the only one of Oldenburg’s 41 site-specific pieces ever to have been removed, even temporarily. Last summer, I wrote for D Magazine about the Nasher Sculpture Center and James Turrell’s site-specific outdoor work Tending, (Blue) that may be affected by the proposed Museum Tower that will loom over the site. Does the DMA also have egg on its face?

Whether the DMA acted with perfidy or legitimate expediency is hard to know. The art world is filled with shenanigans. Museums operate in part by the Golden Rule. That is, the person with the gold makes the rules. And when the trio of great collector-benefactors—the Hoffmans, Rachofskys, and Roses—made their own bequests to the museum under Jack Lane’s watch, we had a clear sign that tastes and procedures were changing.

Dallas has a history, even more than the rest of the country, of tearing things down and starting over. The policy of “newer is necessarily better” is a kind of mantra here. Just look around any neighborhood to see what qualifies as “old” architecture. “Make it new,” advised Ezra Pound in the heyday of modernism, but he didn’t mean “knock it over” or “hide it from view” if it’s old.

Contemporary art is naturally the hardest thing to assess. Museums collect stuff in the hope of getting tomorrow’s acknowledged masterpieces at today’s bargain prices. (Pillsbury said he’d heard Stake Hitch is worth about $20 million.) They are making bets on future appreciation—financial as well as aesthetic—but not all gambles pay off, which is why most museums had a policy, before about 1940, of not buying work by living artists. The DMA’s first full-fledged curator of contemporary art, Robert Murdock, was a fan of Color Field paintings. According to Brettell, the DMA has significant holdings of the work of Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Larry Poons, much of which has also been in storage for a decade or more. These artists were popular in the ’60s. Now their star has declined.

Will we see them again? Will Stake Hitch return to the OK Corral? Only time will tell. If something lies buried in storage long enough, no one will even remember we have it.

Write to [email protected].