Across the street from the Dallas Farmers Market you’ll find a footnote to one of the city’s biggest political blunders. Called City View at Farmers Market, the development stands next to an apartment complex along a road whose name was changed in February to César Chávez Boulevard. The small group of $300,000 brick townhouses now has its third address in as many years because of a public opinion vote conducted by the city. Council members and minority-group advocates have hailed the name change as a victory for Dallas’ growing Hispanic population. The only problem: the political kerfuffle that led to changing the street name has landed the five City View homeowners in a sort of urban Bermuda Triangle where neither mail nor fire trucks nor hungry dinner guests can find them.

When Perry Homes built the property in 2006, the developer gave the houses an address on a shared access plat, or access road within the property, called Central Market Lane. But two years later, Dallas Fire-Rescue requested that the street name be changed because emergency crews were having trouble finding the houses. So Central Market Lane became South Central Expressway.

John Farrell, an attorney at Haynes and Boone and an owner of one of the Forgotten Five, went from living at 905 Central Market Lane to 906 South Central Expressway without moving an inch. “It’s someone [at the city] saying, ‘I’m going to change your address and I don’t really care about your concern. It doesn’t affect me and I don’t know what you’re going through,’ ” Farrell says. His voice shifts from anger to resignation as he talks about the headache of owning a house with three addresses and the lack of response he’s gotten from city staff and elected officials. Farrell and his neighbors frequently receive each other’s bills, checks, and packages in the mail. They also worry about the potential nuisance if they seek to refinance a mortgage. It appears as if they’ve all moved twice in three years.

Even before the recent name change, getting to Farrell’s house was a challenge. Type “906 South Central Expressway” into Google Maps or a GPS, and you will arrive at the intersection of South Central Expressway and Marilla Drive. The first time I tried to find his house using Google Maps on an iPhone, I ended up driving around lost for an hour before giving up. It wasn’t until I had a “Who’s on first? What’s on second?” conversation with Paul Nelson, one of the city’s chief planners, that I understood the cause of the confusion.

When the city changed the name from Central Market Lane to the far less pastoral sounding South Central Expressway, it failed to update the street’s name on its maps—the same maps that are relied upon by the U.S. Postal Service, every major shipping company, and GPS. But how often those updates get made is unclear. “The survey vault has a lot of that information on the older streets, but I don’t know how well that’s kept up to date,” Nelson says.

That’s why it didn’t surprise Farrell that even the city of Dallas couldn’t find him. When it came time to schedule an early public hearing on South Central Expressway’s proposed name change, the city sent Farrell’s notice to the old Central Market Lane address. Farrell made it to the city’s planning and zoning hearing despite the error. He was one of only two to speak against the name change. State Representative Rafael Anchia (D-Dallas) and League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) officials were among the dozen or so people who spoke in favor of the change, but it might as well have been two against 20,000.

“I don’t care if it’s called Polka Dotted Lane if my UPS guy can get here with the sales literature that I need for my job,” says Ashley Anderson, Farrell’s neighbor, who made as many hearings as she could. She’s a regional sales director for a national bank chain, and she’s trying to refinance her home. “But it’s the fact that it will be my third address in less than three years and no one is listening to me.”

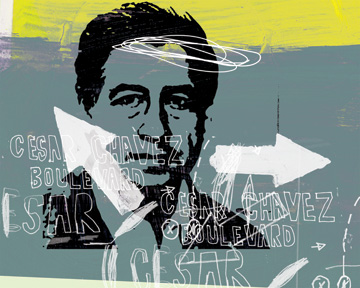

Finding a street to honor César Chávez has been a political fiasco since the day in 2008 that the City Council asked residents to vote on a new name for Industrial Boulevard. The vote was supposed to be a way to get residents excited about the Trinity Project. Industrial ran along the northern levee, an area that figures to see redevelopment as the Trinity Project takes shape. But the city got a surprise when, instead of a name with aquatic connotations, the clear favorite, with 21,420 votes, was the name of a Hispanic civil rights leader who had no connection to Dallas. César Chávez Boulevard didn’t exactly sound like an address that would inspire developers to imagine high-rise condos with views of kayakers playing on the river.

The City Council said, “Thanks, but no thanks,” and changed Industrial to Riverfront Boulevard—but everyone promised that Chávez would get his street. The fight moved to Ross Avenue, then to Young Street, and finally to the stretch of South Central Expressway between Pacific and Grand avenues. Each time, the pressure on the city’s Hispanic council members mounted.

Though the consensus on the Council is that South Central Expressway is a perfect fit because Chávez founded the United Farm Workers union and the street is home to the city’s farmers market, Councilman Steve Salazar admits that it was the path of least resistance. “Look at the different streets that could be considered,” Salazar says. “This street has the fewest number of homes or businesses that could be impacted.”

But don’t blame Salazar for sounding like he just got done fighting a battle he wasn’t ready to wage. Getting a Dallas street named for Chávez was a political issue that truly began at the grass-roots level. When the public vote was conducted, Ray de los Santos was the district director of LULAC, Dallas’ largest Hispanic civil rights group. He says the majority of the votes for Chávez were coordinated by students. “For the adults, it had not registered as that big of an opportunity,” de los Santos says. “It was our college students, our high school students that led this. And then they came to LULAC, and we used the LULAC infrastructure. It was the social networking. It was the Facebook and the MySpace. It was a real youth-oriented movement. We saw the power of that with the MegaMarcha [for immigration reform] in 2006 and the walkouts that happened right before that.”

LULAC created the César Chávez Task Force to coordinate its renaming efforts. The group forced a Council divided along racial lines to come up with a solution and pass it unanimously. No small feat when you consider that even San Antonio doesn’t have a street honoring Chávez.

Now Farrell and his neighbors are left to live with the consequences of a political fight that got buried in their backyard. “It just seems that it was railroaded through without much thought about what we’re doing here,” Farrell says. “It’s a farce at this point. Three streets they’ve tried, and they’ve failed—and those were high-profile streets. It’s not an honor.”

Write to

[email protected]

.

The Cost of Change

19 standard blades @ $175 = $3,325

6 mast blades @ $350 = $2,100

City property notification = $444

News notice = $900

Total cost to city = $6,769

This does not include the cost of changing the exit sign at the southern tip of North Central Expressway. Cost figures reported by Rudolph Bush in the Dallas Morning News.