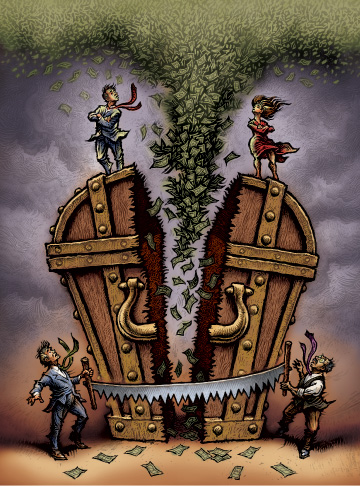

This much we know for sure: Dallas County divorce filings were down from 2,375 for the last three months of 2007 to 1,789 for the last three months of 2008, a drop of nearly 25 percent. “I do not believe Dallas is special,” Becker told me. “One force delaying divorce during bad times is the cost of getting a divorce. This means that marital discord during recessions may first show up as separations rather than legal divorce.”

As with all things, these costs are magnified among the wealthy, where the stakes are higher. So, has the fiscal crisis had an effect on divorce among the wealthy in Dallas? Most everyone in a position to know agrees that it has. But their answers vary greatly.

Since county figures say nothing about a divorcing couple’s income, to find out whether hard times act as a brake or a spur to the most moneyed demographic, we must rely on anecdotal evidence from those in the professional categories that minister to wealthy couples enduring troubled marriages in a troubled economy: lawyers, shrinks, and jewelers.

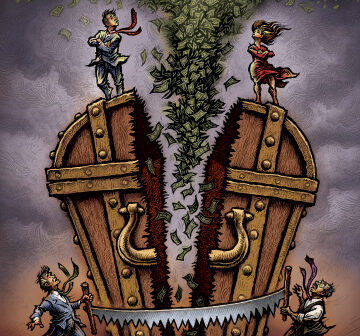

“While divorce filings may be down in general, the numbers among the wealthy are pretty much unchanged,” says divorce attorney Janet Brumley. Brumley then brings up renegotiation, a well-worn topic of discussion among all the lawyers interviewed for this article. “Never before have payments been tied to the price of crude,” she says. But that’s exactly what is happening now. Brumley offers an example: a woman recently divorced an oilman. When oil was above $100 a barrel, he felt comfortable paying $85,000 per month. He thought to himself, ‘Even if it gets down to $50, I’ll be okay.’ But when oil hit $33, he was not okay.

“If the woman enforced the original agreement, it would force a sale of all his assets at bargain prices and would bankrupt him,” Brumley says. “And, after all, he’s the father of her children. Instead, they are negotiating a way for his payments to be lowered and pegged to the price of crude with a floor and a ceiling and a longer payout with interest. Now, this would be a terrifying prospect for someone who was getting $8,500 a month and had to pay all her bills from that, but it’s not so much of a crisis at $85,000.”

Considerate behavior, noblesse oblige, or enlightened self-interest?

A no less practical set of sensibilities is recounted by attorney Ron Massingill, who also feels that the divorce rate among his wealthy clientele is unchanged. One recent couple, whose worth had dropped by millions, realized that they still had plenty left and just split it down the middle. They felt that if they waited, they were just wasting time. “Two of my clients ran into each other recently,” Massingill adds. “One of them, just divorced, said, ‘I’m worth half as much today as I used to be.’ The other replied, ‘I’m also worth half as much as you used to be, and I still have my wife.’ ”

Still, while everything remains relative, the remark gives rise to a passing thought: is there really such a thing as a friendly divorce? None of the lawyers I talked to actually laughed at the question, but attorney Mike McCurley brought things back into perspective.

“I’m seeing fewer divorces at the moment because uncertainty breeds fear, and fear is contagious,” McCurely says. “During bad economic times, divorces go down. It’s not that bad times bring couples closer and salvage marriages; it’s more that people become cautious. As happened after 9/11, there’s a pause and then the divorce rate makes up for lost time. To the degree that divorces among the wealthy may be up, it’s because, if you’re the moneyed spouse with a lot of assets that are difficult to divide, this may be the right time to file. Especially if you can negotiate a long payout.”

Longer payouts for divorce may be part of a larger emerging trend in the current Dallas economy. Brad Todd, a principal at The Richards Group and arts activist, sees this happening with charitable giving as well. “Donations to the Symphony are off, but less than you might imagine,” he says. “Instead, large donors are stretching out the length of their gifts. The Dallas Center For Performing Arts had an original goal of $275 million, which ran up to $350 million. They’re stretching it out, not cutting back. Same for SMU, which launched a $1 billion drive in September with a 10-year horizon. Now it may take 20.”

According to McCurley, “Lots of people see bad economic times as a form of leverage. They say, ‘Let’s redo the deal.’ Since the driving force is fear, and that fear is reinforced every time we hear how tough the times are, some people are able to use it to their advantage. The sad part is that these days, once a marriage ends, you see people fighting more over kids—visitation, custody rights, duties and obligations. Co-parenting is going into a slide.”

Prenuptial agreements are becoming more common, too, McCurley says. “In this economy, the non-moneyed spouses and their lawyers are being less bashful about negotiating hard. Love may blind you, but people are very money conscious right now.”

One man who knows a lot about prenups is a leading Dallas high-end jeweler, a person who sometimes hears about a planned divorce before the lawyers do. “I’ve supported many trophy wives for years,” he says. “I help them plan how and when to sell their jewelry. The prenup figures into this. While one woman told me, ‘I’ll sell the refrigerator and stove before I’ll sell my jewelry,’ many others see this as their livelihood between marriages.”

“I find that divorce is actually up among the wealthy,” says Dallas psychoanalyst Burton C. Einspruch, the lone person interviewed to have observed an increase. “So many of their marriages were ill-conceived to begin with, and declining assets lead to increased use of drugs, legal and otherwise, more family violence, and more DWIs. A DWI is often the last straw in a marriage.”

Einspruch also sees more split-ups among what he calls “pseudo marriages,” couples living together on a long-term basis. “These don’t show up in the statistics down at the courthouse,” he says. “Dallas is a fun-oriented place with many fragile relationships, couples who think about divorce in a chronic way. With some, hard times represents a moment to be opportunistic.

“There’s a sign in my office: ‘I hate my life, but I love my lifestyle.’ For many in Dallas, there’s no context for an economic downturn,” Einspruch says. “They’ve never seen hard times. There’s a firm sense of entitlement, and that entitlement becomes the core part of existence for some. Suddenly it’s gone. Suddenly there are unemployed bankers in Dallas, but the pressure for ostentatious wealth persists.”

But now there appears to be a new sense of caution among those who still have wealth. “The rich guy who flips ’em once in a while used to be more cavalier about money,” says lawyer McCurley. “Now many of them consider risk management. A lot of moneyed men are in high-risk enterprises. And here’s one area of life in which, with a prenup, they can contractually insulate themselves from risk.”

Which may be a lucky thing. As one veteran of several marriages and an identical number of lucrative divorces puts it: “To see a man truly naked, watch his behavior when his money’s gone. Not a pretty sight.”