The most hilariously unsportsmanlike moment in sports history occurred in a hockey playoff game last April, and it starred Sean Avery, one of the newest members of the Dallas Stars. So far, it has gotten about a half million views on YouTube.

The most hilariously unsportsmanlike moment in sports history occurred in a hockey playoff game last April, and it starred Sean Avery, one of the newest members of the Dallas Stars. So far, it has gotten about a half million views on YouTube.Avery, then the left-winger and agent provocateur for the New York Rangers, had been skating like an angry bee beside, behind, and in front of the opposing goalie, Martin Brodeur of the New Jersey Devils. They had words. Avery can zing—“You didn’t deserve your gold medal,” he once informed a member of Canada’s Olympic hockey team during a game—but this discourse was puerile. “Your genitals are of insignificant size.” “And yet your sister seemed pleased during our recent assignation.” That kind of thing.

Then—inspiration. With two members of Brodeur’s team in the penalty box, the Rangers had a five-man-to-three advantage. Avery positioned himself directly in front of Brodeur, but facing him, and paying no attention whatsoever to his teammates or the puck. For a jaw-dropping 30 seconds or so, while television announcers said, “I’ve never seen this before,” the pest blocked Brodeur’s view by waving his arms and stick in front of the goalie’s face and aping his every move. Fearing a penalty for—what, ice dancing?—a teammate bumped into Avery to get him to stop, but he didn’t stop, not until the puck slid to the opposite end. Avery retrieved it, came back, and scored on Brodeur. Injury added to insult. New York won.

“Nobody should have to play hockey with a stick an inch from your face,” Brodeur told the media afterward. “While he was doing it, I couldn’t see anything.”

On Hockey Night in Canada, the venerable Don Cherry said, “He’s a good hockey player, but he acts like a jerk. … What Avery did, I don’t want you kids copying it, because he has no honor, and he hasn’t got respect.”

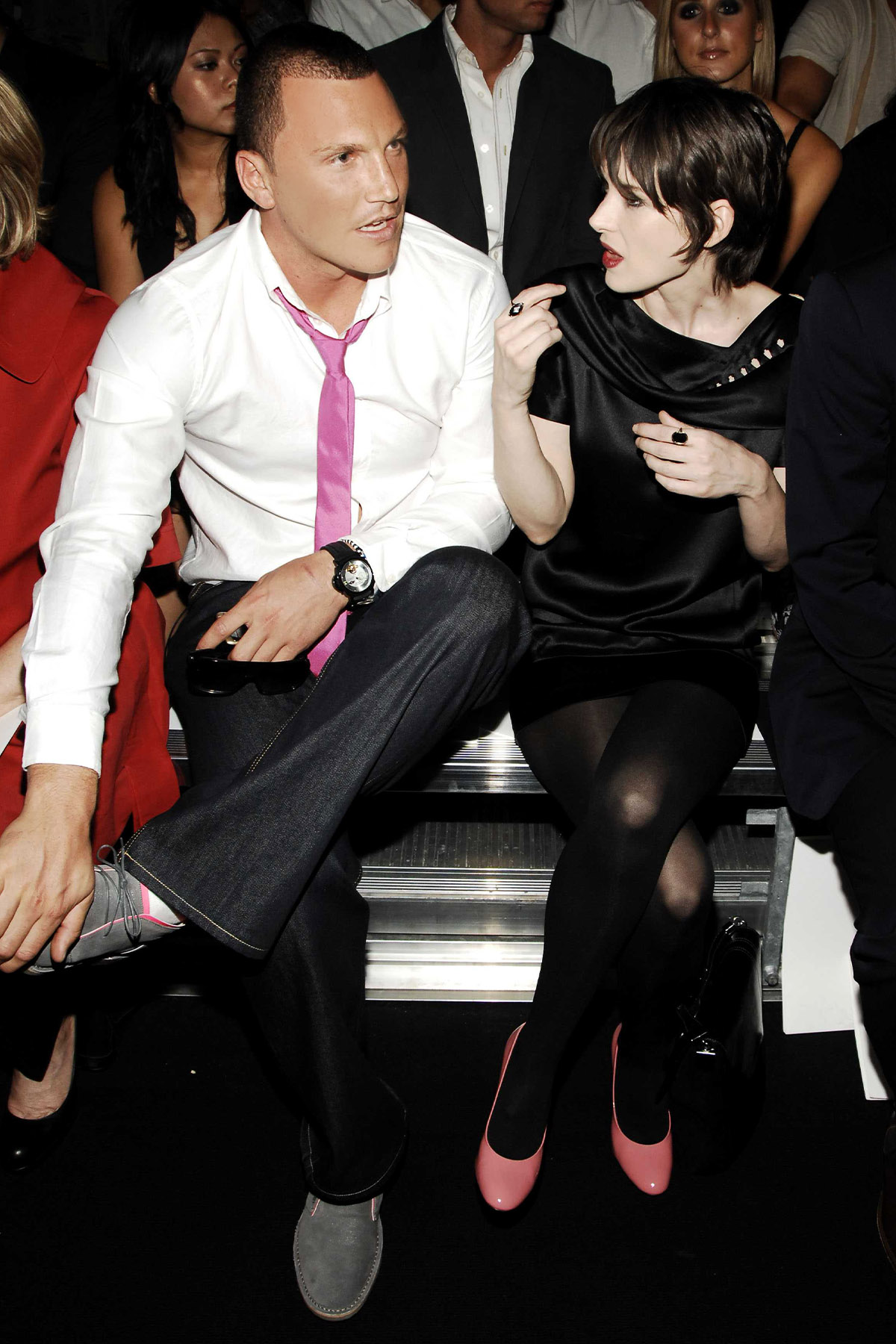

[img-credit align=”alignnone” id=” 862163″ width=”1200″]

[/img-credit]

[/img-credit]The next morning, the NHL announced that henceforth such behavior would result in a two-minute penalty. Everyone calls it the Avery Rule, a bizarre bit of immortality for an unusual man. For like a nun with a gun or a dachshund that can drive a car, Avery embodies contrasts so discordant it almost hurts to think about it. On the one hand, he is thoughtful, soft-spoken, and articulate. On the other, he is a maniac who has twice led the league in penalty minutes. He’s quarreled—loudly—with teammates, opponents, an assistant coach in Los Angeles, even a broadcaster. “You’re a horses— announcer,” he shouted at Brian Hayward, a former goaltender who does TV color commentary for the Anaheim Ducks. The Hockey News polled current players last season to discover the most hated man in the National Hockey League. Avery won in a landslide.

What would be the most extreme yin for the yang of this combative athlete? Neurosurgery? Philately? Buddhism? No. Fashion floats the Avery boat. In fact, our new left-winger cares so deeply about fashion at its high end—designers, designs, photography, and commentary—that he applied for and got an internship at Vogue this past summer. Editor Anna Wintour—the bitch goddess who inspired the book and movie The Devil Wears Prada—knows publicity when it passes her the puck, so Avery reported to 5 Times Square and got a picture ID and a time card. He made minimum wage and made everyone take him seriously—not an easy thing, given his income (now about $4 million a year) and the number of times his picture had been in the Post with actress Elisha Cuthbert and Kelly Klein, Calvin’s ex. His stint at the magazine will serve as the basis for a romantic comedy to be produced by New Line Cinema. But Avery took his job seriously; he attended editorial meetings, assisted with photo shoots, and edited an issue of MensVogue.com. In his 1,600-word valedictory, he explained his summer vacation.

“It’s simple,” Avery wrote. “I like clothes. Always have. What started innocently enough with my first tie-dyed Chip & Pepper shirt at age 12 has evolved over a decade and a half to a closet full of Dries Van Noten, YSL, Dior, and Costume National, to name a few.”

Avery spent a week crafting his essay, his first published work. Although the piece is entertaining and cogent, it hints at a kaleidoscope of conflicts within his conflicts. His closing thought does more than hint at the obvious one: “If you feel like teasing this hockey player about an obsession of his that you think is a little unusual, go right ahead. Just know that you may get your ass kicked by a very expensive pair of shoes—and that they’ll probably match both my belt and my shirt.”

Gliding on ice on steel blades is a gentle, hypnotic activity, ideal for first dates. The rhythm of legs and breath leads to effortless speed and a waking dream that “The Beautiful Blue Danube” is playing nearby. Add sticks and a puck and two goals, and the feeling of abandon morphs but does not disappear, and the soundtrack is less Johann Strauss II and more Foo Fighters.

That hockey became the national sport of the most polite country on earth must be a good thing, eh? Perhaps on some level, Canadians and the fast and furious game need each other. A Toronto boy named Al Avery seemed to need it. Sean’s father played forward, and he was good. “Major junior,” Al says. His voice is manly but soft and uninflected. “The Ontario Hockey League. Most go from there to the NHL, but I went to university instead, on an academic scholarship, then taught college PE after that.”

Al met and married Marlene, another teacher, and they had Sean and, eight years later, Scott. They put their oldest boy on a peewee team when he was 7. He didn’t like it. Couldn’t skate. “He wasn’t gonna go back, but his mum talked to him,” Al says. “She’s the only one he’s ever truly listened to.” Marlene explained that there was a position for boys with mobility issues: goalie. Sean returned to the rink, but the goalie thing didn’t last. He discovered that not only could he skate, he could fly.

“If you feel like teasing this hockey player about an obsession of his that you think is a little unusual, go right ahead. Just know that you may get your ass kicked by a very expensive pair of shoes—and that they’ll probably match both my belt and my shirt.”

excerpt of essay by sean avery published in vogue

Few Americans understand junior hockey in Canada. The corollary is not to junior anything in the United States. It’s much more like minor league baseball—a gritty professional league just below the majors. Kids in their middle teens leave home to live in a faraway city and spend six hours a day with blades on their feet. Age restrictions are enforced now, with 16 as a minimum, but for years these kids and their parents lied about their birthdays like Chinese gymnasts. The displaced players attend the local school, but education is not the point in this system. They’re paid a stipend—making them pros in the eyes of the NCAA and thus ineligible for college hockey in the United States—and they ride endlessly on buses over icy roads, eat fast food, and nurse the bruises from a fight or a forecheck.

Avery’s junior hockey experience produced, he says, “some of the best memories and friendships I’ve had. We’d billet with random families. Just going to high school, playing hockey, no money, no pressure. They’d give us $100 every two weeks.”

A team in Halifax wanted him when he was 14, so off he went. Later he skated for the Owen Sound Platers (northwest of Toronto on the Georgian Bay); the Kingston Frontenacs (several hours east, at the confluence of the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario); then in Cincinnati, for the (then) Mighty Ducks. Junior hockey kept young Sean in a rink almost all the years of his youth, estranging him from his little brother and defeating his slight interest in education (he didn’t finish high school). But the teenaged Avery was being graded and evaluated constantly by coaches and scouts, and getting As. Exceptional skater and above-average stick handler and scorer, his report cards read. Intelligent, sees the ice well. Probably too small for the big time but strong and quite willing to battle. “He gets that from his mother,” Al says. “She’s very fiery and aggressive.”

Do you remember Sean’s first big fight? Yes, Al says. Prince Edward Island.

About half of hockey fights simply erupt, like lava. Somebody slashes or trips or hooks, and the freaking refs are blind. In the standard ritual, sticks are thrown down, then gloves, then right fists are cocked while left hands grab the opponent’s jersey to secure and steady the target, the other guy’s cabeza. No one wastes time on body shots. Combatants whale each other’s faces pink or dripping red, the refs step in, and penalties are assessed.

Thirteen-year-old Sean’s first big rumble was the other kind: premeditated, with at least a few seconds to form intent.

It was a tournament game, Al Avery recalls, with lots of people watching. The puck bounced out of the corner, and the opposing goaltender left his protected area—the crease—to retrieve it. “Sean decided to take him out,” Al says simply. Did he ever. The bullet of a kid from Toronto shot into the heavily padded boy so hard that he had to leave the game. Goalies are regarded as a team’s most valuable player, and teammates are duty-bound to protect them. Sean’s bit of calculated violence was therefore extremely unpopular with the other team and its fans. There was shoving and colorful language. Boos rained down.

The ferryboat trip back to the Nova Scotia mainland required 75 minutes. “That was a very cold ride,” Al says. Parents from the team with the injured goalie wanted to throttle his boy, but his father held them back. “I’ve escorted him out of a lot of arenas,” Al says. “No one from the teams he plays against really likes him.”

Avery came to town in August to meet the media and to find a place to live. We met at Bar of Soap, across the street from Fair Park. He wore jeans and a white t-shirt, a look that said: I can wash my car in this if I want.

The usual shorthand to describe an athlete’s corpus doesn’t help that much with Avery. He’s 5-foot-10 and 195 pounds, but so is a friend of mine who sells insurance. Avery seems to be wearing a super-hero muscle suit beneath his clothes, and surrounding his tree trunk neck are a tangle of necklaces, including one with a bullet and one with two keys.

“Hi, nice to meet you,” he says. “I think you know Nicole?” Avery is the only player in the NHL employing a personal publicist, and Bragman Nyman Cafarelli, of which Nicole Chabot is a media director, is known more for clients from the world of pop culture (not that the company makes its client list public). She does not—thank you—sit in on our conversation at a booth near the door.

“I feel like I’m in New York,” Avery says, putting down his Bud Light. “This reminds me of Queen Street West in Toronto or a lot of places with nice vibes on the Lower East Side. I like people with a little substance, artistic people.”

It’s sort of an arty atmosphere at Bar of Soap, with the paintings on the wall for sale and a heavily inked bartender and a painted black cinder block performance space in the back, near the washing machines. We can hear the thrum of bass and the two girl singers from a band from San Antonio called Ledaswan. During his two years as a New York Ranger, Avery decompressed by visiting similar spots as much as five times a week. Rock, not jazz or blues or klezmer. He’s got Sparta, Mars Volta, and Sleeper Car on his changer at the moment. He likes Radiohead, too, and just went to one of their concerts.

“I’m just looking for a place to get comfortable, not somewhere to talk about the game,” he says. “I’m sure there’ll be times when the guys want to go to the Ghostbar or W, and I’m not opposed to that but this place has a band and a pool table, and I can do my f—ing laundry while I’m at it.” And not be recognized. Perhaps the wonderful combination of attractions at the Bar of Soap causes him to declare, “I think this is where I want to live.”

For a while we discuss the social possibilities were he to acquire a large industrial space in sight of the Cotton Bowl—“If I build it, they will come,” he says—but the next day our new winger would put down a deposit on an apartment near the Ritz on lower McKinney (which turned out to be a prescient move, as Bar of Soap would shutter a few weeks later).

Who might he entertain in his new three-bed, three-bath? “I tend to pick a little more high-profile women, but it’s not because I like to get my picture taken. I like girls with a vibe to them, like an artist or an actress.”

The girl on his arm need not be into fashion. “I’ll wear the designer stuff,” Avery says. “I don’t care about her shoes.”

Avery goes on a bit in his mild voice about music and books and clothing and the two designers he particularly likes at the moment, Alexander McQueen and Helmut Lang. He finished Moby-Dick last month, he says, and is now trying to get through Ulysses, by James Joyce—an autodidact’s heroic effort to be more interested and interesting. Meanwhile I’m wondering what a Frontenac is, and picturing Avery as a 7-year-old, and the first time he got sent to the principal’s office, for screaming into the ear of a classmate. The other child was deaf; little Sean required proof. Now he is calm, subdued even, but if we were on skates I know he’d trip me and taunt me into a bad mistake.

At the press conference at the American Airlines Center, the new Star wears a white t-shirt, a summer-weight red plaid sports coat, matching shorts, and dusty red Alexander McQueen shoes, untied, no socks visible. It’s a look that says: you want to make something of it?

“The first couple of years I had a short fuse,” Avery says. “If something upset me, I’d just react to it. I have to put the team first. But we’re out to win a game. Whatever it takes to help my team win, as long as my team will benefit, I’m gonna do it.” Then, in PR-conscious afterthought: “Of course, I still represent an organization.” He uses the Canadian pronunciation: “organ-EYE-zation.”

Avery drains his third and last Bud Light and walks to the back to watch the band.

Eleven hours later, at the press conference at the American Airlines Center, the new Star wears a white t-shirt, a summer-weight red plaid sports coat, matching shorts, and dusty red Alexander McQueen shoes, untied, no socks visible. It’s a look that says: you want to make something of it?

Dark-suited co-general manager Les Jackson begins the show with a statement that fails to rise above cliché: “Brings a lot of different things to the game … will help take us to another level … .” Behind him, Avery is taking off his jacket so he can slip on his black Stars sweater for the five TV and two still cameras. Jackson picks up the red plaid rag. “Nicest jacket I’ve ever had,” he says, and it gets a laugh.

The questions begin. Ric Renner—the TV guy with the lemon meringue hair—makes the excellent point that some of Avery’s nastiest fights have occurred against Dallas, and with Stars star Brenden Morrow in particular. That gonna be a problem?

“You almost have more respect for guys you’ve battled,” Avery replies. “We leave it on the ice and don’t hold grudges. … It’s gonna be tough for other teams to play against us.”

There’s a pause, and he answers an unasked question: “My personality off the ice is surprising to most people. I’m pretty mellow. The way I act on the ice is almost like a character.”

Where that character comes from seems plain. When Avery finally made the big time, it was with the Detroit Red Wings, Brett Hull’s team. The superstar allowed the rookie to live with him and his wife, an incredible turn of events for Avery, who, as a 12-year-old, had painted “Hull of a Shot” on a sheet and taken it to a game at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto. Hull was a magnetic figure, with his blonde hair and gung-ho style, but little Sean was too embarrassed or mesmerized to hold up his sign.

“It was fun watching him mature,” Hull says. Now he is the Stars’ other co-general manager and a beloved figure for scoring the winning goal when the Stars won the Stanley Cup in 1999. “I knew he was gonna be great. He was constantly learning and then training in the off-season with Kris Draper. No one trained harder.”

But those fights and penalty minutes—we assume you’ll ask Avery to throttle back a little? “Absolutely not!” Hull says. “That’s exactly what we want! He’s got a fiery personality and he makes plays. He’ll add electricity. He’s gonna ruffle some feathers. We need to add some spice to what we have. Our core of Marty [Turco] and Mike [Modano] and Brenden—these guys are all great—but we need more bite.”

Avery approaches the next element of his whirlwind trip to Dallas—a photo shoot for D Magazine—like a fashion professional. With seven people in a conference room at the magazine’s offices, he unselfconsciously strips down to his underwear and begins trying on clothes that style director Stephanie Quadri has borrowed from Neiman Marcus and LFT, a fashion-forward shop in Victory Park. None of it works.

“No, I would never wear this,” Avery says, examining his look in a floor-length mirror. “I would never wear this jacket with this. I hate these pants more than life itself.” Offered a fedora, he makes a sound like a small animal that has just been shot, by way of communicating that he will not be wearing a fedora. In the end, he settles on the clothes he’d brought with him. They are new—with price tags still on— and made by Ann Demeulemeester and Costume National.

“I knew his style was very specific and it would be difficult to choose clothes for him,” Quadri says. “His look is very casual but upscale—and complicated by his body. His thighs are so huge. He’s definitely not conservative. He does not like suits. He said he’d wear these things to a black-tie dinner. In Dallas? Good luck.”

The shoot itself takes place down the street, in a walk-in freezer at Eatzi’s. Again, Avery strips to skivvies to change into the outfit that was deemed too wrinkle prone to make the short trip on Avery’s actual person, as photographer Elizabeth Lavin and her assistants fiddle with cameras, lights, and a portable fog machine. The shelves outside the freezer hold gallon containers of Grandma’s Molasses, Heinz Vinegar, Bertolli olive oil, Kikkoman soy sauce, oats, and matzoh meal. The red tile floors are shiny and slick from just being washed. Employees go about their business while 10 people huddle in a tiny space to watch Sean Avery have his picture taken.

“Now look away—now look back—a little smirk. Good! That’s great! Can we have some more smoke?”

“Layered necklaces are very cool this season.”

“Hey, Sean, tell us about the necklaces. What do the keys mean?”

“The keys are to the pools at the Beverly Hills Hotel and Chateau Marmont. Very important keys to have.”

“And what about the bullet?”

“That’s in case I ever need a bullet.”

We have time to contemplate the network of scars that trace Avery’s face beneath the stubble and, of course, his clothes. He said that a main appeal of custom apparel to him is that it tells a story. The story I’m getting is that he can afford Gucci. And that Gucci makes this powerful man feel even more powerful.

The shoot seems to go on forever, but Avery remains cooperative and calm. He looks away, looks back, little smirk, until the photographer has enough.

About three hours later, Avery’s crazy days in Dallas reach a suitably odd crescendo. He’s been asked to throw out the first pitch before the Rangers-Yankees game in Arlington. He strides to the mound, throws the ball, acknowledges the applause—standard stuff. But in the booth with the TV guys later, the hockey player reappears. Avery says that he would have thrown a better ceremonial ball if not for the six or seven Bud Lights he poured down his neck in the clubhouse—and, too, he says he tried to throw a knuckler. And when Yankees catcher Ivan “Pudge” Rodriguez is carried off the field after a collision at home plate, our new winger scoffs.

“I’ve taken bigger hits than that during warmups,” he says.

The next morning, on television and radio interviews, he does not apologize.

Write to [email protected].

Get the ItList Newsletter

Be the first to know about Dallas' best events, contests, giveaways, and happenings each month.