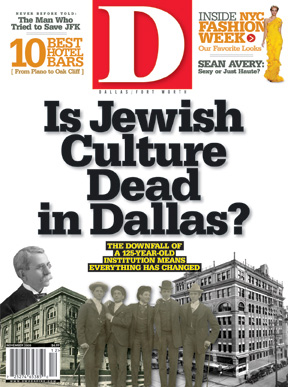

photos courtesy of the Dallas Jewish Historical Society

|

| MEMBERS ONLY: The club’s building on Ervay and Pocahontas streets burned in 1931. |

The building is as big as a city block and simply beautiful, a clean architecture of horizontal lines, pale red brick, and brown painted trim. Live oaks spread their arms to shelter and welcome, and thoughtful plantings frame the whole. But the interior of the clubhouse of the Columbian Country Club gives a much different impression.

|

| An undated photo of members W.M.S. Friend, Ralph Applebaum, Edward Salzenstein, Joe Sidenbitel, and Eli Sanger. |

Dust falls on dust in the deep silence of its 53,000-square-foot interior, a space so vacant that the SWAT squads of the Addison and Carrollton police departments find it ideal for occasional practice of hostage rescue. Plumbing and kitchen fixtures, wood paneling, paintings, furniture, clocks, computers—anything with salvage value is gone. A phone directory in a thin metal frame by the pro shop door remains unharvested. It’s worthless. No one needs to remember that Octavio in Maintenance was at extension 190 or that there were three card rooms or that the kitchen required four telephones, including one for Ralph, the executive chef. You dialed 180 to speak to Chad, the general manager, and 189 to chat with Tom, the friendly golf pro. The receptionist’s name was Lani. Dial zero.

The Columbian was Dallas’ Jewish country club. Jewish country clubs are not at all unusual, especially in the big cities to our north and east. Chicago had five, New York eight, Philadelphia eight. There were four in the Cleveland-Akron area, where I grew up. I caddied at one of them, an experience that both informed and warped my ideas of wealthy people, Jews, and club life.

Why Jews felt compelled to band together was simple: they enjoyed their own company, and the other clubs were not letting them in. “Restricted” was the now-quaint euphemism for discrimination based on religion. So in nearly every big North American city with a critical mass of Jewish families, they carved out their own slices of country club heaven, and they were usually as good as the clubs that had excluded them (and they always had better food). A lot of this retaliatory golf club construction occurred in the 1920s, when the United States had money, and an appealing young man from Atlanta named Bobby Jones was the best golfer in the world. Everyone wanted to play Bobby’s game.

Founded in 1881, the Columbian owned a longer history than most clubs of any kind in the United States. A lot of people—including D Magazine in 1984—said it had the best restaurant in Dallas (although the property is just over the tracks, in Carrollton). Its golf course ranked behind only the first tier—Preston Trail, Lakewood, Northwood, Dallas Country Club, and Brook Hollow. “When a Jew moved to Dallas,” said Lester Melnick, the well-known retailer, “he joined a temple or a synagogue and hoped to someday be invited to join the Columbian Country Club.” How many weddings and bar and bat mitzvahs did the Columbian host, and how many romances bloomed on the shores of its big blue pool? We can estimate the rounds of golf played—somewhere around a million—but who can guess the number of spritzers and blintzes they served?

|

Now, a wrecking ball awaits. It seems like such a waste, such a miscalculation by some of the smartest people in the city. There’s an epic sweep to the rise and demise of the Columbian Country Club, encompassing great men and social trends and revealing a corner of history that historians too often ignore—what people do for fun. But the final days of the club have been, well, complicated. A lawsuit painted a formal backdrop of petitions and restraining orders for shouting and fracturing friendships. Tiger Woods was involved, in a way, as was a gunslinger of an out-of-town consultant—albeit a gunslinger in a good suit and with an English accent. A plucky band of Columbian survivors still stands, for outside the doomed clubhouse the jewel-like golf course remains. The course has a new name—The Honors Golf Club of Dallas—and a new vibe. Tony Romo is a member, as is Stars goalie Marty Turco.

Will this new club survive? It matters. About $20 million is at stake.

My employer at the Jewish club where I caddied would arrive on the first tee, vivid in red pants and redolent of cologne. “What’s your name, son?” he’d ask kindly.

“It’s Curt, sir,” skinny teenaged me would say, clutching the man’s heavy leather golf bag.

“Okay, caddie, gimme my 3-wood.”

Whether the trousers were green or red or purple, this tableau played out so regularly that we bearers stopped noticing. I was thoroughly disoriented: new to golf and to puberty, and I’d never met a Jewish person as far as I knew. My ever-changing roster of bosses amazed me. They began sentences with “so” and ended them with “already” and asked a lot of questions of me and of each other. “So where did the ball go?” “So what do you want from me?” “Why can’t I putt, already?” Schmuck, schlemiel, schvartze, plotz, oy veh. I learned and started using a score of funny new words. The members tipped like they were giving blood, which is to say reluctantly, if at all.

I drew conclusions about Jews from this small sample, including that they were wealthy, parsimonious, often hilarious, and horrible at golf. But I learned only one true thing, confirmed, eventually, by working at five other courses during the next 15 years: our members loved their club and made a day of it whenever possible.

|

| FIRST CLASS: The front and back of a 1908 postcard that shows the Columbian Club building. It had a bowling alley and gym in its basement. |

Some will view the very existence of Jewish clubs as a shameful extension of Old World ostracism and persecution. Not that there aren’t abuses in this sliver of society—try joining Dallas Country Club, Mr. Goldstein!—but there is joy in banding together with people who look like you and talk like you and believe what you believe. We get enough melting pot in public schools and at the Cowboys game. Private clubs have their place, and they’ve been around forever.

For example: the Young Men’s Hebrew Association formed in Dallas in November 1881, ostensibly for the “mental, moral, and social advancement of its members,” according to its charter (in those Victorian times, social associations required a lofty-sounding raison d’être). But the YMHA re-branded in 1890, led by seven Young Hebrew Men who apparently desired more contact with Young Hebrew Women. The seven, who were regulars at a downtown dance hall called the Phoenix, persuaded the YMHA to change its name to the Phoenix Club. Meetings were held at the dance club at the corner of Jackson and Ervay.

A bond sale and the support of the merchant princes of Dallas—Sanger, Harris, Kahn, Gordon, Sakowitz, Neiman, Marcus—enabled the construction of a clubhouse elegant enough for their daughters’ debuts. The new place at Ervay and Pocahontas opened in 1905. It had a bowling alley and a gym in the basement, with dining and reception on the first floor. The top level had a hall with a stage, and that marvelous new invention from Mr. Edison, a phonograph. Perhaps as an effort to distance itself from its dance hall days, the club took still another new name: the Columbian Club.

This was the lay of the land: for about four years, beginning in 1913, while Temple Emanu-El built its new home on South Boulevard, the Columbian hosted Seders (Passover dinners), Hebrew classes, and confirmation and post-confirmation classes. A couple of early 20th-century Dallas mayors belonged to the Ku Klux Klan. Our other private clubs—except Lakewood, where the Sangers had a presence—would not admit Jews. But neither religion nor retreat from anti-Semitism was the point of the Columbian Club.

“My father became a member of the club in 1910 at age 25,” Lyra Brin Daniels says. “He met Boots Badt in September 1922 at the Opening Ball. They married in January 1923. My father played poker at the club twice a week in the afternoons—on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

“Eddie and I met at the club in December 1946,” she says. “We had our first date on December 31. Since that night, we have been at the Columbian Club every New Year’s Eve for 59 years with only two exceptions: the year Eddie came down with the flu and in 1954, for the birth of our first child.”

|

| DANCING WITH THE BARRS: Whoever owned this piece of ephemera, on at least one occasion, she literally had herself a full dance card. |

As it was for Lyra and Eddie, who married—at the club, of course—in April 1949, the Columbian was an extended family. And it was a Ball—Inaugural, Masquerade, Presidents, Anniversary, and Candle Light. Perhaps the latter led to the fire of 1931, which burned the place almost to the ground. With impressive speed, and despite the Depression, the club acquired land on Garland Road overlooking White Rock Lake and had another clubhouse open in less than two years. The new place had a pool, a bar, card rooms, and a view. But: no air conditioning, not enough space, and the adjacent land was too expensive to annex for the golf course more and more members wanted.

To judge by the hectoring tone of the letter sent to the membership by the board of directors in 1951, the club had hit bottom:

For many years the Columbian Club has been an unprogressive organization and has finally reached a low ebb in its history. Certain members have resigned in the last two years because they feel the club has little to offer. The continuing members have, by and large, shown such a complete lack of interest in the development of the Club and its activities that a serious question has been raised in the minds of many about the advisability of the Club’s continued existence. …

The Dallas Jewish community is entitled to have a fine country club of which it can be justly proud. … We are one of the few cities with an outstanding Jewish population that has neglected to build a proper club. … With this in mind, the Club Directors have taken an option on a piece of property north of the present City limits. The property covers approximately 326 acres and the Directors envision an outstanding Club with all the facilities a discriminating membership would require.

The proposal to buy the land and to build a grand club passed. Columbian had joined the modern age—and sowed the seeds of its own destruction.

Single malt scotch began as mere Scottish moonshine, a low-cost alternative to cognac. Opera was a rowdy amusement for music lovers who couldn’t afford the symphony. Golf morphed similarly, surviving for hundreds of years in Scotland, England, and Ireland as pasture pool, a fast, affordable hike on seaside acres for men and women of every income level. But when it arrived in the United States during the Gilded Age, the game became upper-crusty—mostly because of clubhouses. They had huts to store the clubs and a cubbyhole for a bottle of whiskey. We built palaces.

|

| DRESSED FOR SUCCESS: Some women at the Columbian were determined to wear the pants in that club. |

Not until after World War II and the advent of Arnold Palmer did American golf begin to loosen its tie. Arnie, arguably the first television sports star, had more ham in him than a prize pig. He won or lost thrillingly, then signed your program, and yours and yours and yours. Every sector of golf, including the private country club, enjoyed robust health during Palmer’s reign. But today’s leading light is much dimmer. Tiger Woods attracted new golfers but couldn’t keep them (and he doesn’t do autographs). Participation has plunged, falling from 6.9 million very avid golfers (25 times a year or more) in 2000 to 4.6 million in 2005, according to the National Golf Foundation.

One impossible-to-ignore factor in the game’s declining popularity is how freaking long it takes to play it. The fiction—thanks, Tiger!—that even high handicap golfers need precise yardages to every target, and that greens must be examined before putting as if you’re deciding where to dig the well, have added, probably, an entire hour to the ordeal. Golf is exhilarating when done in three hours but it’s excruciating in the new norm, five. Add the things you do at a private club—a shower, a meal or two, and a beer or two, and the day is done. Do we really want Daddy wearing golf shoes all weekend?

|

| Others were on the fence. |

Dicey economics, changing gender roles, and increased choice from new high-end daily fee courses also threaten the country club life. “Don’t forget pools,” says Craig Prengler, a former member of the Columbian Country Club. “Since the ’80s, everyone who builds a new house also builds a pool. You don’t need to go to a club to swim.”

Jewish clubs face another, particularly sticky challenge: low birth rates. There aren’t enough Jews to go around! Westwood in Houston, Brynwood in Milwaukee, Hillcrest and Brentwood in Los Angeles, two of the four Jewish clubs in Cleveland-Akron, and three of the eight in Philadelphia—all are no longer Jewish-only. And the great new private clubs in North Texas—including Dallas National and Gleneagles—don’t give a sou if you go to a temple or to a church. They don’t “restrict.”

So the Columbian Country Club raced into the inscrutable future, not knowing that it was driving toward a cliff. The new club just north of Beltline in Carrollton opened in 1955. Total cost, including land, was about $800,000. The clubhouse required half of that amount, four times more than the nine-hole golf course, because it was four times more important. Golf was for working on your tan. “Men are requested not to remove their shirts until the first green,” a club pamphlet read, “and to put them on again at Number Nine Tee.” The formula worked, because membership jumped from 348 in December 1954 to 428 a year later.

Golf’s role in the club ascended, eventually, as nine more holes were dug out of the dirt in the ’60s, and all 18 benefited from a facelift in 1998. But brunch and lunch and cards remained supreme. Thanks to a $3 million investment in 1984, the clubhouse grew to its present size. Within it gleamed a new 6,000-square-foot kitchen for the best restaurant in Dallas.

The years went by. Heated and air-conditioned indoor (of course) tennis courts were added. Imperturbable Fred Ablom seemed to win the golf championship every year. Wednesday became synonymous with chicken dinner at the club, and the Sunday night buffet was a ritual. Even when he was chairman of the Democratic Party or ambassador to the Soviet Union, Robert Strauss always found a way to get back to the Columbian for the Saturday night poker game. Membership peaked at about 600. But at some point in the ’80s or early ’90s, for the reasons discussed above, the balloon began to lose air.

Members heard the hissing sound every month when they opened the mail. As membership fell, dues hopscotched a hundred bucks at a time from a baseline of $300 to $900 per month. The Columbian cost more than anywhere in town except for the billionaire boys’ club, Preston Trail.

“I came onto the board in 2000,” says Charles Zelazny, a second-generation member. A wiry man with a deep tan contrasting with his gray hair, Zelazny owns an employee benefits company called Taxsaver Plan. “After going to two meetings, it was obvious to me that we had big problems that were not being looked at in the right way. We began to organize committees that would give us direction, to plan. Let’s plan on what’s gonna happen.”

The board played around with schemes to attract new members from the shallow pool of Jews of the right age and income level. “It didn’t seem to matter what we tried,” Zelazny says, and his voice trails off. “No matter how we priced it—”

In late 2005, the board met to discuss hiring Los Angles-based consultant David V. Smith, whose Golf Projects International handles development, marketing, and operations. Zelazny and a handful of others sat at the big conference table in the Phoenix Room at the club, an airy rectangle with a pink and rose-colored carpet over a parquet floor, and floor-to-ceiling windows. It was a grim moment. “If we hire him, you know it’s the end of the club as we know it,” someone said, for they all realized Smith might recommend something drastic. “If we don’t hire him,” replied another board member, “it’s the end of the club anyway.”

|

| CERTIFIED: In 1920, Louis Oppenheimer paid $100 for one share of the Columbian Club. Though the golf course still stands, the club no longer exists. |

The consultant arrived in January 2006 and got the lay of the land. It wasn’t good. “Columbian Country Club was at death’s door, with all nails in the coffin save one,” recalls Smith. He’d seen this before: a club running a growing monthly deficit makes some last-ditch efforts to save its bacon and winds up making things worse. “Membership drives and discounts turn out to be detrimental,” Smith says. “They cause a decrease in image and perceived value.”

Smith had also observed groups as polarized as the ones at the Columbian, with half the members purely social and half gung-ho golfers. With the club in trouble, the two sides became opposing camps who shouted and swore at each other. The faith that had brought them together would not be enough to keep them whole, for one big reason: there was no one to inherit the thing. The sons and daughters of Todd Aaron and Robert Zelazny had happily abandoned the country club life in favor of more peripatetic activities involving snowboards and soccer practice.

A task force of club members worked with Smith, who presented the findings to the membership. He built his case with bullet points and numbers on a screen, and with handouts with 30-point type. There were pages entitled “Assessment for Operating Loss Over Next 4 Years Based on Historical Trends”; “Other Options Considered” (club merger, partial sale of real estate in three parcels, mid-level club option, club sale); “Market Summary”; and “How Deep is the Jewish Market?”

Jewish population in North Texas (50-mile radius) = 50,000

7.6 percent play golf = 3,800

25 percent play at private clubs or premium public courses = 950

And so on. The conclusions: the club should no longer be strictly Jewish. You should close the kitchen, the tennis courts, the swimming pool, the clubhouse. In fact, bulldoze the clubhouse. You simply can’t afford not to. Rebrand as something the public wants—unless you want to spend about $17 million to expand the clubhouse to 70,000 square feet, to make it competitive with the top clubs in the area. And, let’s see, $17 million divided by about 300 members—does anybody want to do that? The only way for the Columbian to survive is as a golf-only facility. Here is how we’ll do it. We call this the New Day Plan.

Smith is apt to sigh when he talks about this. “No matter how carefully you tread or how well you present, it’s as if they have no receiver for the message you’re sending,” he says. “It was a very difficult assignment to convince them over two years to abandon a 55,000-square-foot clubhouse and a full-service kitchen in favor of a 5,000-square-foot temporary building.”

Smith is British. He understates. “Difficult” does not quite capture the feeling.

Most of the club’s 204 voting members convened at the club to decide on the New Day Plan on December 17, 2006. A CPA watched the ballot box like a hen monitors her chicks. People slipped their votes through the slot and strolled into the dining room. There were Hanukkah lights; the club always looked great for the holidays. Later in the evening, the accountant cleared his throat and announced the results: the golfers had won, narrowly. The socials and those who wanted to sell protested by having some legalistic paragraphs read into the record. Then, they sued.

So—125 years of history came down to this, already: Cause number 06-12960-E, Todd S. Aaron and Ari J. Susman V. Columbian Country Club of Dallas. The Plaintiffs’ First Amended Petition For Declaratory Judgment, Temporary Restraining Order And Other Injunctive Relief accused “the President and the Board, or certain members of the Board, of having a personal interest in gaining approval of the New Day Plan, because they … wanted to be in position to maximize their shares of the proceeds of a liquidation of the Club, if the New Day Plan was implemented but not successful.”

The plaintiffs pointed out that the Club had received an offer of $19,166,400 for its 220 acres, but that this very relevant fact was not shared with the membership before the big vote. Which was true. Whoops. Another offer hit the table the week in February 2007 the lawsuit was filed: Texas Home Partners wrote to say they’d pay $22,603,880.

The defendants had two replies: they had had serious questions about the validity of the offers received, and in no way were they trying to enrich themselves and screw those who dropped out of the club. They just wanted a golf club. This golf club. They knew that the Columbian was possibly the most fun track in town; thus, their passion.

Neither of the lead dogs in the suit, Todd S. Aaron nor Ari J. Susman, wanted to talk about the unpleasant 10-month interval of depositions, writs, and legal fees. But Dr. Ben Schnitzer spared a few minutes from his busy practice of urology at Baylor Medical Center. Schnitzer takes an Olympian view of the demise of his club. “There were other options I preferred to the one they chose,” he said. “But for some remarkable reason, people disagreed with me. We had some knowledgeable people—one, specifically, an architect—who thought we should not tear down the clubhouse. Or you could keep half the clubhouse by getting rid of the big ballroom. Another thing: some of the outlying areas could be sold off for condos. The architect showed where these could be. The condo owners could be members. This was off-handedly dismissed by a couple of people, not really considered, in my opinion.

“The lawsuit?” he says. “It was just the idea of them selling after others had left. Here I am a member for 40 years—but I wish them well. I have many dear friends out there and many, many patients I’ve treated for cancer and stones.

“This was not the apex of my life.”

The honorable Martin Lowy, Judge of the 101st Civil District Court, signed the Agreed Order of Dismissal on December 5, 2007. “Dismissed with prejudice to the refiling of same,” the document read. “The costs of court are taxed to the respective parties which incurred same.” The plaintiffs got some money from the defendants—“a small judgment,” according to Robert Zelazny—and a guarantee that they’d share in the proceeds if the new club goes under before 2012.

They were going to call it The Golf Club at Columbian but decided, finally, that any iteration of the old name detracted from the newness of the thing, its break from the past. The Honors Golf Club of Dallas conjures old-school virtues and hints that tea and cake and swimming—country club stuff—are not on the menu. But this quite unique name was already taken. The Honors Club, in Ooltewah, near Chattanooga, is well-known in golf circles. So “the Honors Golf Club of Dallas” seems strange, like trying to recycle “Augusta National.”

HGCOD looked at the prices of all the private clubs in the area—from Brookhaven’s $3,500 initiation fee and $350 monthly dues, to the $200,000 and nearly $1,000 charged by Dallas National—and positioned itself roughly in the middle. You may join Honors for $30,000 plus $595 per month as this is written, but the price is going up, they say, to $35,000, then $40,000. Discounting reduces perceived value. Lesson learned.

“They didn’t rebrand so much as create a new brand,” says Dallas marketing guru Liza Orchard, owner of Impact Cause Marketing. “Rebranding requires some reference to the previous product, to the past. But today’s Dallas doesn’t care about history. We scrape and re-build. Dallas likes new.”

New members are trickling into the Honors Golf Club, attracted by the intriguing golf course and its friendly staff. If the trickle becomes a stream, they’ll probably erect a much smaller clubhouse where the big old one used to stand. It will have a kitchen. They should serve blintzes.

Curt Sampson’s most recent book is Golf Dads: Fathers, Sons, and the Greatest Game (Houghton Mifflin, 2008).