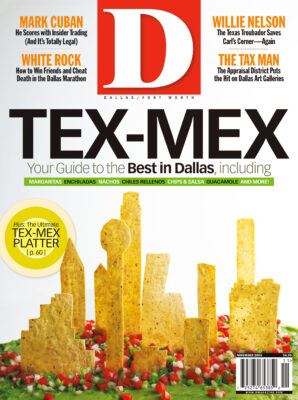

Tex-Mex is the food we come home for. When we return from a trip, many of us drive straight from the airport to our favorite salsa source. We know places where families have served the real deal—rolling enchiladas, stuffing tamales—for 50 years or more. The appetite cuts across the city’s subcultures. Chile con queso is the cultural glue that binds Dallas together. In the following pages, we answer every Tex-Mex question you ever had, plus a few you’d never think to ask. What, for example, is “authentic” Tex-Mex? Who invented the frozen margarita? And is it possible to fit 12 items on a single combination plate?

|

El Fenix was opened in 1918 by Mike Martinez. Photography courtesy of El Fenix |

The Tex-Mex Trail

From Mike Martinez to Mico Rodriguez: How Mexican food, margaritas, and money morphed into Dallas’ most beloved cuisine.

Did the ancient Aztecs eat tostados? That’s not a question we’ll address here, but Vanessa Fonesca did, in her UT doctoral dissertation. That such a question was seriously considered is proof of the breadth and depth of influence Mexican food has on American culture. The Latinization of America started in the Southwest, and nothing has helped bridge the Hispanic-Anglo cultures like cheese enchiladas. Owning a Mexican restaurant was—is—the first bite of the American dream for many Mexican immigrants in restaurant-crazy Dallas, where many businesses wouldn’t even serve Mexicans until the 1930s and ’40s.

The Aztec answer may be lost to the mists of time, but the origin of Mexican restaurants in Dallas is pretty clear. Miguel “Mike” Martinez opened the first Mexican restaurant in Dallas on September 15, 1918, at the corner of Griffin Street and McKinney Avenue, a neighborhood then known as “Little Mexico.” Oddly enough, though, Mike’s restaurant didn’t serve Mexican food. Instead, he served American-style dishes.

|

Adelaida “Mama” Cuellar in the early 1890s with the first of her 12 children: Gabina (left), Hermino, and Santiago. Photography courtesy of El Fenix |

Born in Mexico in 1890, Mike emigrated to the United States, driven by poverty. As a young man in America, he first worked for the railroads, mostly in Colorado. But he didn’t part ways with the rails until he reached Dallas, when he went to work for the posh Oriental Hotel (which became the Baker Hotel), in downtown Dallas, across from the resplendent Adolphus.

At the Oriental, Mike learned cooking techniques that enabled him to open his own cafe. After several months of serving Anglo food, he started making his version of Mexican dishes—tacos, frijoles, enchiladas, and tamales. But the Anglo preference for high-dollar meat demanded that protein-poor Mexican food be beefed up. The result—though no one recognized it at the time—was a whole new cuisine. Much later, it was dubbed “Tex-Mex.” To make the crossover complete, Mike topped the cheese enchiladas with Texas chili. He named his cafe El Fenix.

In the early days, Mexican food was such a novel concept to Dallasites that a 1924 headline in the Dallas Morning News actually proclaimed “Movie Star Successfully Encounters Mexican Food.” In 1931, in a Morning News story titled “I’m Through With the Whoopee Lulas,” Allen Duckworth wrote “Lots of girls have Mexican food complexes. … Once you start going with one they’ll have you down in Little Mexico eating all those fool things that you just have to point at on the menu and take a chance on what you’ll get.”

Obviously the Whoopee Lulas prevailed: 33 years later, Mike and his wife Faustina moved to a larger location at 1601 McKinney.

“In 1964, the city said they needed our property to build Woodall Rodgers,” Mike’s son Alfred says. “We moved across the street, and we moved fast. We served dinner at the old location one night and served lunch the next day in the new place.”

Mike and Faustina had eight children. When the sons got out of the Army, after World War II, they all followed their father into the family restaurant business. So did most of the daughters.

To meet the growing demand, El Fenix and other Tex-Mex cafes expanded out of Little Mexico. Today, El Fenix’s Northwest Highway location, solidly on the cusp of Preston Hollow and the Park Cities, has lines out the door every Wednesday for Enchilada Night. Alfred still works in the McKinney Avenue El Fenix today, though now it’s shadowed by Woodall Rodgers, and Little Mexico has been replaced by the American Airlines Center, Victory, and luxury hotels like the W. And the food that started in Little Mexico has taken over Big D.

Fonseca, our UT scholar with the big questions, posits in her dissertation that one reason Mexican restaurants became popular when they did is because of technological advances. Mexican food menu items such as tortillas, taco shells, and chips are all made from masa. In the early 1900s, making masa for a restaurant was a time-consuming process, and the product spoiled quickly.

In 1909, Jose Martinez of San Antonio patented the Tamalina process that produced dehydrated corn masa. The end result, masa harina, was easily shipped and stored and facilitated in the preparation of the basics of Mexican food. But taste, as much as technology, fueled the Tex-Mex boom.

|

The second El Chico restaurant opened in 1946 in Lakewood and is now Cantina Laredo. Photography courtesy of CRO, Inc. |

There’s a third generation now working at El Fenix, indicative of another precedent established by Mike Martinez in the Tex-Mex restaurant world: this is a family business. But it was the Cuellar family, founders of El Chico, that laid the foundation of the Tex-Mex culture in Dallas. At the peak of their success, the Cuellars’ restaurant company was the largest Hispanic-owned business in Texas, according to John, grandson of Adelaida Cuellar, the family matriarch.

Adelaida emigrated from Mexico, and in 1913 she and her 11 children moved to Kaufman, where husband Macario was the foreman of the Star Brand Ranch and where their last child was born. In 1924, Adelaida, ever the family businesswoman, decided to make hamburgers, enchiladas, and chili and sell them at the Kaufman County Fair. “In one weekend, she made more money at the fair—$300—than her husband made the whole year picking cotton,” John Cuellar says. “She decided there was definitely something to this Mexican food business.”

The Cuellar children grew up during the Great Depression. When they were old enough, they moved away, each seeking his fortune along points of the compass. Somehow, they all ended up following Mama’s footsteps, making and selling Mexican food—in Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas. In 1940, they all returned to Texas, borrowed $500 from their mother, and opened the first El Chico in Dallas at 3514 Oak Lawn Ave., next to Lucas B&B, where Pappadeaux Seafood Kitchen is now. By 1949, they were the largest Mexican food organization in the country, with 250 employees and $1.25 million a year in sales.

Again, the technology was right for the menu. The California produce processing business had received a giant boost during the war. Later in the 1940s, when the troops came home, there was not a huge customer base for all those dehydrated spices and canned chilies. “They started selling to Mexican restaurants in Texas,” John says. “We bought chili powder in 220-pound drums. At one point, El Chico was the third-largest consumer of avocado in the United States.”

|

| The five Cuellar brothers who built El Chico: Willy Jack (left), Mack, Alfred, Gilbert, and Frank, in 1973. Photography courtesy of CRO, Inc. |

The business grew quickly. Another El Chico opened in Lakewood in 1946, one in Fort Worth, two more in Dallas, including one in Inwood Village (now Cantina Laredo) in 1949. In that year, the five sons, “Mama’s boys,” as they were known—Gilbert, Mack, Alfred, Frank Sr., and Willie Jack—pooled their resources to form a single business.

Between 1968 and 1998, the brothers sold and bought back the business six times, making money each time, John says. In 1961, the Cuellars received a phone call from Angus G. Wynne Jr., part of the family that had owned the Star Brand Ranch in Kaufman, where Adelaida raised her family. Wynne was taking a wild gamble on an amusement park in Arlington. He was calling it “Six Flags Over Texas,” referring to the many cultures that make up the state, and he wanted his old friend to run the restaurant in the “Mexico” section of the park.

“That was my first job with the company,” John says. “I was 16. Most people in the United States still didn’t know what a taco was.” On opening day, John got a taste of the taco-mania to come in the next decade. “We ran out of taco shells. We ran out of tamales. We ran out of paper plates and cups.” El Chico at Six Flags was the highest-volume restaurant in the chain.

El Chico paved the way, but other families staked their claims. In 1947, at Sonny Dominguez’s Tupinamba, the fried tacos became famous. Mama Ojeda’s sour cream chicken enchiladas and the hand-patted flour tortillas at Herrera’s drew crowds to Maple Avenue. Austin-style Mexican food came north, first with Pete Dominguez, whose Mexican “pete-za” and George Poston plate at Los Vaqueros were Park Cities favorites.

Over the years, El Chico bounced back and forth from a privately held to a publicly owned company, but the Cuellars were always connected to it. Once a week, all five brothers, multimillionaires with businesses in 14 states, would gather at their mother’s house for lunch. They began to hold holiday family gatherings, which included many El Chico employees, at the El Chico in Fair Park (now the Old Mill).

Mico Rodriguez’s mother was a cashier at El Chico, and his dad was a manager.

“El Chico had a real culture all its own,” he says. “I remember the first time I went to the family Christmas party at Fair Park. There was nothing like it. These were the five godfathers of Mexican food. They had an aura and a presence that was magnetic to me. I thought then, ‘This is what I want to do the rest of my life.’”

Now Mico is co-owner of Mi Cocina, the current top-dog Mexican chain. He wasn’t the only one to be inspired and trained at El Chico. Alumnae are everywhere, and many of the famous Dallas Tex-Mex restaurants trace their roots to El Chico. David Franklin, who founded On the Border, started at El Chico. Chuck Anderson of Abuelo’s used to work at El Chico. Pulido’s was managed by another branch of the Cuellar family, descended from one of the sisters who married Gabriel Gamez. Frank Sr. started La Calle Doce, the first Tex-Mex seafood restaurant in town, and Ranchito and Tejano, the only restaurant still owned by family shareholders. After leaving El Chico behind, Gilbert Sr. returned to the business to open the first Cantina Laredo in Addison in 1984. Former El Chico manager Raphael Carreon opened Raphael’s, which was reincarnated as Rafa’s on Lovers Lane. Desperados, the post-collegiate boomer watering hole founded by El Chico ex George Levy, just celebrated its 30-year anniversary. And Mico’s parents, Ana and Butch Enriquez, opened Mia’s on Lemmon Avenue in 1980. Today, it’s still one of the most popular joints in town.

It was the grandson of a Cuellar who made arguably the biggest technological leap in Tex-Mex history. In 1974, in a restaurant called Mariano’s in Old Town, Mariano Martinez served the first frozen margarita, using a retrofitted soft-serve ice cream machine that now sits in the Smithsonian. The invention of the frozen margarita spawned a whole new genre of Tex-Mex restaurant-bars, where singles came for the drinks as much as the food. The swinging-singles margarita scene spread to Moctezuma’s on McKinney and Genaro’s, where Monica Greene (Monica’s Aca y Alla) met much of her future clientele.

One El Chico alum took Tex-Mex in a different direction. Mario Leal opened Chiquita, the first white-tablecloth Mexican restaurant in Dallas, where the permanent Christmas lights and border kitsch décor were replaced by giant, colored paper flowers. The service was gracious, not just efficient. Leal was famous for his tacos al carbon, steak wrapped in flour tortillas, the forerunner of the fajita.

As Mexican restaurants became more popular with Anglos and the cuisine more familiar, North Dallas began “discovering” Mexican restaurants in Mexican neighborhoods. Everyone had his favorite “secret” Tex-Mex joint—A.J. Gonzales behind KERA on Wolf Street, Cafe Rincón on Harry Hines, Rosita’s on Maple. Guadalajara on Ross Avenue became the place for post-club dining. At 3 in the morning, the place was packed with Norma Kamali-clad cool girls and Stray Cat wannabe boys scarfing down cheese enchiladas with a Tecate.

The tastes of Tex-Mex also seeped into high-end restaurants. Local chefs Stephan Pyles, Dean Fearing, and Avner Samuel were heavily influenced by south-of-the-border ingredients, which laid the foundation for what became known as Southwest Cuisine.

Fiery little British ex-pat Diana Kennedy, in her 1972 book The Cuisines of Mexico, drew an emphatic line between interior Mexican food and the Anglicized Mexican food she called “Tex-Mex.” The term was meant as an insult, implying the bastardization of authentic Mexican food.

“‘Bastardization’ is the perfect term for Tex-Mex,” John Cuellar says. “But Gilbert Sr. used Tex-Mex to describe the food at El Chico way back in 1954. And we’ve got the documents to prove it.”

Bragging rights aside, Tex-Mex has become a cuisine all its own. And the Whoopee Lulas are now chowing down on combination plates in Dubai.

THE PERFECT COMBINATION PLATTER

|

| Photography by Manny Rodriquez, food styling by Brook Leonard and Scott Hartzler |

Face it: we’re emotional about our favorite Tex-Mex fixes. We go to one place with the kids, to another for a couple (or three) margaritas with our No. 5. Lunch? Perhaps the hole-in-the-wall around the corner from the office. Over the last year, we tried them all and concocted our fantasy combination platter by combining our favorite items onto one plate. The result? A last supper to die for.

BEANS

Without beans, there is no Tex-Mex. They’re obligatory on any combo plate but also surface as a not-so-secret ingredient everywhere else: nachos, tostadas, quesadillas, enchiladas, burritos, and tamales. There’s a host of variations, from ranchero and charro beans with bacon, chilies, and tomatoes, to “drunken,” or borracho, beans with beer. But you know what the real deal is: frijoles refritos—refried beans, baby, mashed once with lard and heated on a skillet. Refried-bean perfection boils down to “creamy plus fluffy,” and that’s exactly how they do it at Aparicio’s (216 E. Virginia St., McKinney. 214-733-8600).

RICE

Rice always gets eaten last—if at all, poor thing. It plays the same thankless role in Tex-Mex as in Asian food: stay in the background, fill out the plate, and sop up the heat. Hey, we can’t all be tacos. It’s actually known as “Spanish rice” and feels like an afterthought, despite the Tex-Mex tendency to give it a natty orange tint by cooking it with tomato. Onion, pepper, and garlic are in there, too. Heck, some places go all out and add the random kernel of corn or pea. This lends some much-needed texture, because the rice usually gets so overcooked that you can’t tell one grain from another. The best, found at Margarita Ranch (Mockingbird Station, 5321 Mockingbird Ln. 214-824-3573), is warm and moist and spiked with corn and diced carrot.

TAMALES

Mexicans were toting around tamales long before the Earl of Sandwich invented his namesake snack. These pancakes of ground corn, rolled inside a husk and steamed, were the original portable meal. The big variable in tamales is the filling, and pretty much anything goes: shredded chicken, chili con carne, shrimp, mushrooms, corn, jalapeños, spicy black beans—even fruit and nuts. Modern fillings include gourmet goodies such as goat cheese or sun-dried tomatoes. But if you’re talking Tex-Mex, you’re talking meat, especially pork, seasoned with cumin or chili powder and slow-cooked until it falls apart into long, tender shreds. They’re a specialty and the best at La Popular (5004 Columbia Ave. 214-824-7617).

CHIPS

A moment of silence for Rebecca Webb Carranza, who invented the tortilla chip in 1950 and passed away in January ’06. Determined to recycle the imperfect specimens at her Los Angeles tortilla factory, she cut them into triangles and deep-fried them. Tex-Mex has never been the same. When cut extra thin, they become light and crisp, though sometimes oily. The alternate version comes thick and sturdy, almost like corn chips, primed to stand up to dip. Newer “artisan” chips contain stone-ground or blue corn. But there’s none of that froufrou stuff in Tex-Mex, where pale “restaurant style” chips have but one purpose: to scoop salsa. The best are served perfectly warm and salty at Herrera’s (4001 Maple Ave. 214-528-9644).

|

| THE MASTERS OF TEX-MEX Alfred Martinez, El Fenix (left) A third-generation Martinez, Alfred still pulls two shifts a day at the oldest El Fenix location downtown, where, the family claims, the Mexican food revolution began in Dallas. Once the center of Little Mexico, the restaurant now stands under the shadow of Woodall Rodgers. Little Mexico has now been replaced by the W Dallas–Victory and the AAC, but El Fenix remains. Now with 16 area locations, El Fenix’s famous Wednesday Enchilada Night continues to draw thousands of loyal customers. Matt Martinez, Matt’s Rancho Martinez (right) |

SALSA

Salsa is Tex-Mex’s concession to the requirement for a fresh vegetable, though you might not recognize it as such. Salsa dates back centuries, yet it was the first Mexican food to go mainstream in the early ’90s, when it beat ketchup as the most popular condiment in America. The basic recipe contains tomatoes and chilies, but given the infinite improvisation salsa seems to invite, no two are alike. People add onion, pepper, corn, peas, and beans. They add peaches, pineapple, and mango. They serve it warm. No, they serve it cold. They blend it smooth; they keep it chunky. They pile on chilies for a fiery heat, or they skip chilies for an ultra-fresh taste. Classic Tex-Mex salsa is a red purée, moderately hot, like the good stuff at Avila’s (4714 Maple Ave. 214-520-2700).

Salsa is Tex-Mex’s concession to the requirement for a fresh vegetable, though you might not recognize it as such. Salsa dates back centuries, yet it was the first Mexican food to go mainstream in the early ’90s, when it beat ketchup as the most popular condiment in America. The basic recipe contains tomatoes and chilies, but given the infinite improvisation salsa seems to invite, no two are alike. People add onion, pepper, corn, peas, and beans. They add peaches, pineapple, and mango. They serve it warm. No, they serve it cold. They blend it smooth; they keep it chunky. They pile on chilies for a fiery heat, or they skip chilies for an ultra-fresh taste. Classic Tex-Mex salsa is a red purée, moderately hot, like the good stuff at Avila’s (4714 Maple Ave. 214-520-2700).

MARGARITA

These days, you can be a tequila connoisseur. (Trece has 120 kinds of tequila on the menu.) When we were young, tequila was considered a drug—a hallucinogen, if you want to get picky—as much as a drink. Fifty cents and a lick of salt, taken like medicine, and you were good for the night. Tex-Mex was struggling in the ’70s. It was hard for bartenders to keep up with the demand for good, cheap margaritas, and customers no longer settled for mere beer with their combination plates. Mariano Martinez’s bright idea to make margaritas with Slurpee machines ushered in the era of the Tex-Mex bar—sweet, cold, sipping drinks that could be sold for $5 with a healthy markup. These days, you can’t have Tex-Mex without margaritas. We still like ’em straight up, shaken not stirred, and the Yucatán at Primo’s (3309 McKinney Ave. 214-220-0510) is top-shelf.

ENCHILADA

There are a million kinds of enchiladas. You can find them stuffed with chicken, seafood, spinach, potatoes, and corn fungus (called huitlacoche if you don’t want to scare anybody), but real Tex-Mex enchiladas are corn tortillas softened in hot lard, stuffed with onions sautéed in cumin and grated yellow cheese, and smothered in chili con carne. Period. The best in town are at El Jordan (416 N. Bishop Ave. 214-941-4451). Try them with a cold Mexican Coke.

GUACAMOLE

Of course we like avocado. It is one of the few fruits with natural fat built right in it. Avocados, and supposedly guacamole, date back to pre-Columbian Aztec cuisine. The Mayans apparently ate them, too. The question is, did they make their guacamole with Hass avocados? You can tell by the color: if it’s not made with Hass avocados, the green is too bright. The correct color was immortalized in a million 1970s appliances as well as in a song called “Avocado Green,” on an early album by great Dallas bluesman Johnny Winter. The best guacamole is seasoned sparingly, just enough to set off the natural butteriness of the fruit. But the genius of guacamole on a combination plate is the contrast of its congealed creaminess with the spicy salt of the plate’s other components. That’s what you get at Rafa’s (5617 W. Lovers Ln. 214-357-2080).

TACO

In Mexico, a taco is a fresh, hot tortilla wrapped around shredded meat or beans with a little sauce. The original tacos, real Tex-Mex tacos, are stuffed, held together with a toothpick, then fried. This version, however, is a lot harder to keep indefinitely fresh. The taco, like the margarita, has been altered by technology. Most places now use a pre-formed, U-shaped, machine-made shell that is filled with meat, beans, lettuce, and cheese just before serving. The “puffed” taco—the kind Tupinamba made famous in the 1940s—is made by deep-frying a fresh tortilla so it puffs up like pita bread, then filling the fragile, flaky center so there’s a nest of flavors in the middle. But we think the perfect taco is walking food and can be eaten out of hand, so our favorite is the filled then fried half-moons at Escondido (2210 Butler St. 214-634-2056).

TORTILLA

The tortilla is the foundation of Mexican food—sacred mother corn mixed with water and patted flat. It’s the most basic New World version of the most basic human food: bread. The Spanish called the native Indian food tortilla—their word for “little cake”—and the Mexicans used them as plates, forks, and spoons. In Texas and other states, the Anglos replaced the corn with wheat flour, which contained gluten, and the flour tortilla was born, stronger and more flexible than its corn sister, able to hold a lunch-full of rice, beans, and beef. Very few places in town still hand-pat their own, but Chuy’s serves around 3,500 of their homemade, hand-rolled balls of flour (no lard) tortillas a day (4544 McKinney Ave. 214-559-2489).

|

| THE MASTERS OF TEX-MEX Mama Ojeda, Ojeda’s (left) Cecilia and Bentura Ojeda were broke, busted, and disgusted with Shreveport, Louisiana. Bentura worked in a restaurant. “We had no money, and we had nine kids,” says Cecilia “Mama” Ojeda. “We had so many kids, and we wanted to see them all the time, so we moved to Dallas and started a restaurant.” They staffed their Maple Avenue restaurant with family and used their own recipes for enchiladas and puffed tacos. Today there are five locations of Ojeda’s, each with a family member in control. And the original location? “Mama still runs the original by phone,” her son Tom says. “At 87, she is still the one who hires and fires.” Eddie Dominguez, Tupinamba (right) |

PRALINE

By the time you finish a combination plate, you might want something sweet, but you don’t want much. These days, many restaurants tout flan, the distinctive version of baked custard made with evaporated milk. Others offer sopaipillas, but these are New Mexican sweets. Growing up, we were always offered a simple choice: sherbet or praline. If you chose the former, you got a tiny neon-colored scoop in a stainless-steel dish. But we usually chose the latter, and what could be more Tex-Mex? The candy combines the native Texas pecan with coarse Mexican brown sugar to create a version of the Creole French sweet called praline. In Dallas, lots of Tex-Mex restaurants buy theirs from RJ Sho-Nuff’s Famous Texas Premium Candy Co. (7479 S. Westmoreland Rd. 214-374-5876). RJ’s pralines are 3 inches in diameter, holding complete pecan halves crystallized in sugar like flies in amber. There’s no caramelized, corn-syrup chew here, just quick-dissolving sweetness that disappears on the tongue like cotton candy.

NACHOS

Some say they were first served at the State Fair of Texas in 1954. Others say that in Piedras Negras, just across from Eagle Pass, Texas, a bartender nicknamed Nacho threw together tostados, cheese, and jalapeños for some military wives on a day trip and—ole! He invented the nacho. It has even been said that Howard Cosell made nachos famous by eating them on the air when he was in town broadcasting Monday Night Football from Texas Stadium. Okay, so much for Internet research. What we do know, from our own life experience, is that originally nachos were constructed individually: first a tostado, then a spread of refried beans, then a little shredded cheese, then a ring of pickled jalapeño. Some concessionaire saved time by piling chips on a plate and haphazardly dumping the toppings all over them. Those are the nachos that became sports snacks, served in every ballpark, stadium, and arena in the country. We still like the ones shown individual attention. At Mi Cocina (11661 Preston Rd. @ Forest Ln. 214-265-7704; multiple locations), each little nacho is a perfectly composed mouthful.

CHILE RELLENO

The best chile relleno came to Dallas via Austin, but Matt’s Rancho Martinez (6332 La Vista Dr. 214-823-5517) has been in Dallas now for 20 years, so we can justify it. Owner- chef Matt Martinez’s father and grandfather served this version to generations of UT students at El Rancho, the first Tex-Mex restaurant in Austin. The Martinez chile relleno is a seeded Anaheim chile, filled with a choice of stuffings (we like the shredded beef), battered in buttermilk and flour, and fried until the crust is crisp and the pepper is cooked. The whole thing is sauced with ranchero and sprinkled with chopped pecans and raisins, crowned with a dollop of sour cream. Then it’s rushed to the table, before the crust starts to wilt and sag under the sauce. Besides the à la minute presentation, unusual amid the casserole style of so many Tex-Mex dishes, Matt’s chile relleno is distinctive in that it threads back through Mexican culinary heritage, through Spanish cuisine, to the Moors from Northern Africa, who conquered and brought their complex food, flavored with layers of dried fruits, spices, and nuts.

|

| BIG ENCHILADA: Mico at his restaurant in West Village. Photography by Tadd Myers |

The New Boss

Mi Cocina founder Mico Rodriguez made Tex-Mex respectable.

Mico Rodriguez strides into the Mi Cocina at West Village, wearing a custom-made shirt and Ferragamo shoes, and he’s rushed at the entrance by a coterie of customers and employees. “mico!” hollers one diner. A server pleads with him to visit one of his tables. Manager Walter Rosales steps into the melee to escort Mico inside.

They might as well kiss his ring.

West Village would seem to represent a personal best for the 49-year-old Dallas restaurateur. Two of his concepts, Mi Cocina and Taco Diner, occupy prime slots in this trendy retail center. Sweeter still, they sit directly across from each other—and both thrive.

“This appetite for Mexican is so incredible that it even amazes me,” Mico says, sounding as if he just found a $20 bill on the ground.

His success has become self-perpetuating. The bigger his M Crowd empire becomes, the more ambitious it gets. West Village is a pit stop for a larger urban zone: New York, where a Taco Diner—the sixth—is scheduled to open at the end of 2007.

The M Crowd, of which Mico is CEO, includes 15 branches of Mi Cocina across North Central Texas and one in Kansas City, plus Mercury Chop House, Mainstream Fish House, five Taco Diners, and the upscale Mercury Grill. But Mi Cocina, serving good old Tex-Mex, is the backbone of his empire.

Mico started paying his dues at age 6, when he worked as the fabled water-boy at El Chico, where his parents, Ana and Butch Enriquez, worked until 1980, when they left to open their own place on Lemmon called Mia’s. Backed by partners Ray and Dick Washburne and Bob McNutt, Mico left Mia’s in 1991 and opened the first Mi Cocina with his wife Caroline on Preston and Forest in 1991. (Full disclosure: our food editor has a relationship with Dick Washburne—as of press time.) With Mi Cocina, he took what was formerly a primitive, funky dining experience and elevated it into something respectable—chic, even.

“I used to eat at his mom’s restaurant and became one of his first customers when he opened in Preston Forest,” says Mercury Gill executive chef Chris Ward. “He did what PF Chang’s does, which is to add a boutique atmosphere.”

In the process, he changed our perception of what a Mexican restaurant should be.

“I felt that the Mexican restaurant world in the 1980s needed a little more sophistication than broken-down buildings painted pink or yellow,” Mico says. “The whole deal back then was ‘border.’ They went totally theatrical, with Don Pablo’s, Uncle Julio’s, On the Border. That is not what I wanted to do. I felt like somebody needed to go back to the example set by El Chico in the ’60s, which was elegant.”

Bringing Mi Cocina to Highland Park Village put it over the top, Ward says.

Mico does much of it himself; he has an eye for design. For Taco Diner, he expanded on the contemporary cleanness he’d created at Mi Cocina, creating a minimalist-modern interior with cool periwinkle and lime colors.

“I can remember when I was young, walking to Neiman Marcus downtown, where I studied the cosmetics counter, looked at the lighting, saw everyone enjoying the experience,” he says. “I was always aware.”

His influence now permeates the local Tex-Mex scene, most tangibly in a wave of places that have duplicated his formula. One of the first knock-offs was Anamia’s, opened in 1996 by former M Crowd employee Jay Ortiz, now with three locations. Then came Rio Mambo Tex Mex y Mas in Fort Worth, opened by former M Crowd manager Brent Johnson. There are now two.

Luna de Noche was opened in 1998 by Lisa Galvan-Cuevas, with her brother Eddie Galvan, who worked for Mico for many years. Lisa and Eddie are siblings to Mico’s wife Caroline. Luna just opened its sixth branch in Victory Park.

In 2005, Eddie left Luna de Noche to open Casa Milagro in Richardson, joined by Arnold Nitishin, who worked with the M Crowd for 12 years, most recently as director of operations.

Meanwhile, Mico’s uncle Manny Rios (the Manny after whom Mia’s “Mannychanga” was named) opened Manny’s Tex-Mex in 2005 on Lemmon Avenue, barely a block from West Village, with a former Mi Cocina cook in the kitchen.

“These guys went to Mico University and they learned,” Mico says. Less directly connected but still part of the Mico-Caroline family are Manny’s Tex-Mex in Frisco, owned by Caroline’s cousin Richard Galvan, and Ricardos Tex-Mex in Allen, owned by Richard’s son (Caroline’s nephew) Kevin. Confused yet?

“Mico University” refers to Mico’s program of finding and developing managers for his company. Most of the day-to-day business is executed by 1,200 intensely loyal employees, most of whom have worked for him for 14 years or more.

“My job is to develop other Micos—that’s the rest of my career,” Mico says. “How do you find someone that can’t live without this business?”

“There’s a lot of people they’ve brought through the system,” Ward says. “You find a waiter that’s familiar with one of the stores and make him manager. People know that he’s made a lot of lives.”

Along the way, he made a lot of lives.