|

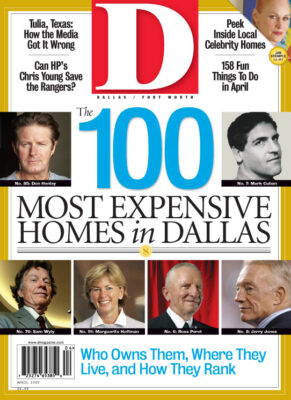

| TALL BOY: Highland Park grad and Princeton alum Chris Young can throw hard and think smart. |

Imagine discussing theistic baseball with a man who attained just about every on-the-field tangible that the sport has to offer. This is Orel Hershiser, pitching coach of the Rangers, a man who appears on the Johnny Carson highlights video, amazing his host with an impromptu and stirring tenor rendition of the doxology. So it was perplexing when Hershiser, a man of deep-water spiritual convictions, listened to my most cherished of baseball beliefs and said, “I think that’s a big load of bull crap.”

The point of discussion was a moss-shrouded theory embraced during previous generations: in baseball, God didn’t give out good minds with good arms. In other words, pitchers, as opposed to the everyday hitters and fielders, could receive remedial high school credits for watching Sesame Street.

Hershiser dropped the gauntlet. “Jim Palmer? Ever meet Jim Palmer? Think he’s dumb? Or Tom Seaver? Bob Gibson? How about Sandy Koufax? Now there’s a real moron for you.” Hershiser, the National League Cy Young Award Winner of 1988, same year SI tabbed him Sportsman of the Year, was steamed.

Huh. Hershiser produced five minutes of compelling testimony for the exceptional thinking processes of the big-league pitcher. Strong stuff, but it tended to contradict directly my recollections of Ranger hurlers from the past. I am talking about a memorable assembly of orally fixated miscreants who had as much difficulty locating their hotel rooms as they did the strike zone and were frequently seen peeking at the front page of the morning paper to determine what day it was. These were pitchers like Charlie Hudson, who missed a couple of months because of a self-administered accidental gunshot wound, and Roger Moret, the man who turned himself into a naked statue before a game and was hauled away to the psych ward. When people mention Rangers pitching to me, it’s the likes of Hudson and Moret who spring to mind.

So who’s right here? The expert, Hershiser, or the long-suffering pragmatist, me? Rangers fans, with the 2005 season looming upon us, better hope that it’s Hershiser. That’s because a key element in the Rangers’ plans to contend for post-season playoff reservations this season, perhaps the key, happens to be a pitcher whose academic background would tend to belie his occupational status.

Meet Chris Young. He’s a graduate of Highland Park High School and Princeton University, with a degree in political science. That’s the part that bothers me. Poli sci and Cy Young hardly go hand in hand.

But, based on what Young demonstrated toward the end of the 2004 season, he could become the elusive piece that the Rangers so desperately require to remain competitive throughout the regular season. Despite a season of bright surprises in the win column in ’04, beyond Kenny Rogers and Ryan Drese, the team’s starting staff was a shambles. By mid-season, poor Hershiser, not to mention his boss, manager Buck Showalter, felt more like guest judges on American Idol than the brain trust in the big-league dugout.

This was the staff that seemed to consist of Rogers, Drese, and whoever had four days’ rest at the Rangers’ Texas League affiliate up in Frisco. By the end of the season, Texas had auditioned 17 starting pitchers. No team in the major leagues could top that. The number also tied a team record, equaling the number of starters who took the hill in 1973, the year that Hudson shot himself. But that ’73 team lost 105 games, which was the most futile of all Rangers seasons, while last season’s team won 89 games and competed for a playoff spot.

Thus the basis for the optimism that prevails as the Rangers approach the 2005 campaign. Should Chris Young build on and improve the basic skills that he demonstrated in his big-league audition in the final month of the season, then the team will have its third dependable starter. That would serve to stabilize the team’s alarming revolving-door pitching rotation.

So what makes this Young character so different from the pack, other than the expanded mental capacities that the Ivy League degree implies? Well, for openers, Young happens to be 6 feet 10 inches tall, and the presence of such a creature standing upon the elevation of the pitcher’s mound, glaring down at the hitter, offers intriguing possibilities.

“That height, when you consider the natural angle of delivery, should provide the 6-10 pitcher with an advantage,” Hershiser confirms. “There are some components, about six, that you look for in a major-league pitcher.” Hershiser talked about “open-body torque” and “muscle-fiber twitch,” along with other desirable kinesic traits that sounded disturbingly like rocket science. “Given those factors, I’d rather have a 5-10 guy with all of the outstanding technical fundamentals than a 6-10 pitcher who didn’t have them all,” the coach said.

So how many of Hershiser’s magic components does Young bring to the party? “He’s got them all,” Hershiser says. “But at the major-league level, so does about anybody else.

“The separator becomes this: when the pitcher confronts his lifetime dream, does he become nervous, excited to the point that he can no longer perform? That’s the determinant.”

Viewed from that perspective, Young’s transcript now appears even more intriguing. Here’s Young’s story as he attempts to position himself as the first hometown hero to play for any of the area’s four major pro franchises since the late Harvey Martin, defensive end for the Cowboys.

Young grew up on Bryn Mawr, east of Preston Road, and attended University Park Elementary and McCullough Middle School. By the time he reached HP as a 10th grader, Young was about 6-6, still growing, and endowed with athletic skills that would make him the biggest multisport star that HP had witnessed since the days of Doak Walker and Bobby Layne during World War II. Young earned all-state honors in basketball and baseball, leading the Scots to the state tournament in both sports, winning the title in the latter.

By the end of his high school athletic career, Young faced some life-altering decisions. College or pro? Basketball or baseball? He recalled the process as he sat in Gordo’s, where he was a frequent customer in his high school days, and gazed across the street at the folksy little HP baseball field, the place they call Scotland Yard.

“Assuming that I was going to college, I wanted to play both sports,” Young says. “Several places said they’d be willing to allow me to play both, but they made it known that baseball would be a secondary consideration because basketball is a revenue-producing sport in college and baseball isn’t. So, under that circumstance, the basketball coach would get the ultimate say-so as far as my career was concerned.

“But I got the opportunity to attend Princeton, where they don’t give athletic scholarships,” he says. “And that way, I could have a little more control of my sports destiny.”

Very mature thinking on Young’s part. Get those childish college years out of the way first, earn that Ivy League diploma with all of the job uncertainty that comes with that these days, then settle down with the lifelong security of a real profession—in sports.

After Princeton, though, there were more choices. Major League Baseball or the National Basketball Association? The Sacramento Kings desired his services. Again, Young pondered his options. Baseball would come first. Helluva choice. In the world of the NBA, being 6-10 offers no advantages. In baseball? Well, just look at Randy Johnson.

So, Princeton degree in hand, he disappeared into the obscurity of the minor-league hinterlands and served a two-year apprenticeship in locations like Hickory, North Carolina. He originally signed with the Pittsburgh organization, then was swapped to Montreal, which is a lovely place to visit, and, were it not for the realities that everyone there speaks French and no one appears to have realized that the franchise even exists, it might have been as good a place as any to play major-league baseball. Young, by now, was thinking more and more about a hoops career.

Then his sports destiny intervened. In one of those under-the-radar transactions that proliferate in baseball’s pre-season springtime, GM John Hart engineered a minor-league trade that brought Young to the Rangers. “Of course, I was delighted at that,” Young says. “As a kid, I was an avid Rangers fan. Even after I signed, when I was playing in the minors with other organizations, I’d check the standings every day to see how the Rangers were doing.”

Young was stationed at Frisco, in the AA ranks, to refine his technique. Then, late in August, he got the call from the Rangers. He was “going to the show” and soon it would be time, like Hershiser says, to confront that lifetime dream.

Two starts at Ameriquest Field produced mixed results. Against the Minnesota Twins, Young didn’t last five innings, although the Rangers won on a ninth-inning home run. In his second start, against Baltimore, a day game in Arlington, Young encountered some control problems. But for three innings, while Young had his stuff, Orioles batters appeared intimidated by the 6-10 rookie. Imagine that. An intimidating presence on the mound wearing a Rangers uniform. The franchise hadn’t seen that since Nolan Ryan retired and, for that matter, produced precious little in the intimidator category in the 17 years before Ryan came to Arlington. Then, during Labor Day weekend, Young came face to face with the moment that may define his career.

On September 3, 2004, the Rangers’ charter flight landed at Boston’s Logan Airport at 4 a.m. Throughout the day, Young had trouble working in a few hours of sleep before the night game against the Red Sox. He was too excited about seeing Fenway Park and was aflame with the prospect that the following afternoon he would pitch there.

By then, cosmic forces were clearly at work in Boston. The baseball miracle that ended the 86-year-old Curse of the Bambino was approaching, and the Sox fans could feel it coming on.

“Fenway Park is more than I could have imagined,” Young says. “The atmosphere is that something is about to happen. Manny Ramirez hit a home run, and the place simply erupted, just went nuts. Yeah, it was a bad moment for our team, but I’d never experienced such sheer energy in a baseball stadium. Since I was starting there the next afternoon, I wanted to just inhale that atmosphere—feed off it, if possible.”

Fenway Park, with its Green Monster, the short left-field wall that eats pitchers alive and devours careers, is not a venue where rookie pitchers conventionally desire to tread. Young claims he couldn’t wait to get to the park. “I got up early and actually walked from the hotel to the ballpark. There were plenty of Sox fans walking over there with me, the ones who wanted to get there early, although they didn’t have any idea who I was. I just wanted to drink it all in.”

Young went through his pre-game routine, stretching and having a trainer massage his golden arm. “It’s kind of dark in that area in the tunnel that leads from the clubhouse down to the dugout. So I walked through that and then outside and saw the green field and that late summer sky over Fenway, perfectly blue. It was an overwhelming feeling.”

How did Young fare when facing his lifetime dream? He pitched to the very maximum of his capacities. When Showalter finally came to remove him from the game, there were already two outs in the bottom of the sixth and Young had yielded but one run en route to his first major-league victory.

After losing his next start, Young rebounded with six shutout innings against the California Angels in a game that the Rangers won 1-0—their first 1-0 win dating back 669 games.

Rookie performances that come late in the long season are so often only a tantalizing mirage, the byproduct of an adrenaline-charged kid enjoying the role of the can’t-miss prospect against weary veteran players crawling toward the oasis of the completion of a fatiguing campaign. Still, the Rangers won five of the seven that Chris Young started, and he looked stronger and more in command with each trip to the mound.

What can the Rangers—and, needless to say, Rangers fans—expect this season from the hometown boy? There were no guarantees that Young would even appear in the big-league roster going into the regular season, though the team did give him a contract that pinpointed his sports destiny for the next three years.

“The last thing we will do is put undue pressure on Chris,” Hershiser says. “What we expect of him this year is that he will perform at a level that forces us to use him.”

Still, Hershiser cannot deny that the 6-10 kid with the Princeton education has potential. And there’s the rub. It was Whitey Herzog who looked at what were touted as bright pitching prospects before that dismal 1973 season and observed, “From a manager’s standpoint, potential is what gets you fired.”

Mike Shropshire is an author and career writer. His first D Magazine article, “The Looney Legend,” appeared in October 1980.

Get our weekly recap

Related Articles

Try the Whole Roast Pig at This Mexico City-Inspired New Taco Spot

Raychael Stine’s Technicolor Return to Dallas