THE VOICE ON MISTY KEASLER’S ANSWERING MACHINE THAT Saturday in June was urgent. “I’ve got your heroin addict. I’m in the emergency room at Piano Medical Center. Grab your cameras and come quick.”

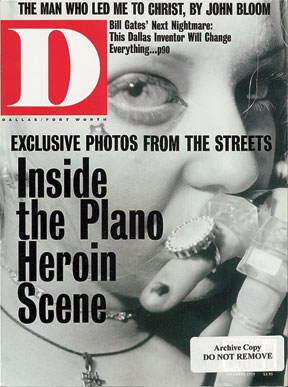

Misty couldn’t believe her ears. For weeks the 21-year-old photography student had been looking for a way inside the life of a heroin junkie, a Piano heroin junkie. She had never tried drugs herself-“Not even pot, and everyone’s tried pot”-but like a lot of people in Piano, she knew plenty of kids who had. Indeed, her closest friend, Jason, had only recently been released from rehab following a prison sentence for possession of heroin. But the image she wanted to photograph now-the image of a junkie this close to death-was the image she had never witnessed herself. She knew her best chance of capturing it was to find her way inside the emergency room during those critical minutes following an overdose.

Belita Nelson, the woman who left the message-two hours old by the time Misty heard it-didn’t give specifics. Who was the addict? Would the kid’s parents allow a photographer to take pictures? And what about the E.R.? From past experience Misty knew the emergency room to be an unwilling participant when it came to recording life-and-death moments. She’d have her answers soon enough. For now she grabbed her cameras, stuffed a handful of model -release forms into her bag, and flew out of the house.

Misty had been pestering Nelson for weeks: “Find me a junkie.” “Have you found me a junkie?” “When are you going to find me a junkie?” Misty’s former speech teacher ai Piano East Senior High, Belita Nelson now heads The Starfish Foundation, a nonprofit drug prevention and awareness organization she founded in 1997 after a .string of heroin deaths threatened to turn Piano into the heroin capital of suburban America. But Nelson is more than a concerned citizen, more than a liaison for Misty. Her own son-Misty’s friend, Jason-spent five years in and out of drug rehab before Nelson, desperate to get him off the streets and away from the dealers, called the police and had him arrested for possession of heroin.

It was last June, six months after Jason’s release, that Belita Nelson and Misty Keasler began talking about how they could put a face to the Piano heroin statistics ( 18 Piano-related heroin deaths in the last three years). Although officials citywide are anxious to point out that the crisis has abated, heroin use is not a thing of the past. “It’s just gone underground,” says Nelson. “When you have heroin as cheap and as plentiful as it is out there, you have addicts, and when you have addicts, it’s not over.”

As executive director of The Starfish Foundation, Nelson has developed a blueprint for combating drug abuse in schools across the country. The plan-a combination of drug-prevention education, community involvement, and strategic programs-outlines the responsibilities of everyone in the community, from schoolteachers to grocery store clerks. Through speaking engagements and television appearances (Oprah, Leeza, Nightline), Nelson discovered an audience eager to hear the testimonial of a suburban mom whose life took a dramatic detour because of a drug once confined to the darkest corners of the ghetto. In describing the ravages of heroin, she found that words alone are woefully inadequate. She needed a visual aid to deglamorize heroin.

Misty, meanwhile, needed a subject worthy of her second photo documentary.

In the years since she graduated from Piano East (class of ’96). Misty has switched her focus from drama (her first two years were spent studying theater at DePaul University in Chicago) to photography. After she moved back to her parents’ home in Richardson a year and a half ago. she enrolled in a course on “visual anthropology” at Collin County Community College. More than just a beginning photography class, the course concentrated on the study of people through their culture. Her first project-a series of black-and-white photos chronicling seven months in the life of a woman battling brain cancer-resulted in a showing at Piano’s House of Black & White; the exhibit caught the attention of The Dallas Morning News, Piano Profile, and the Piano Star Courier and led to a scholarship at CCCC. The success of that first foray into photojournalism guaranteed her second-whatever the subject might be-a showing at the school’s new gallery. As she listened to her old friend Jason talk about his addiction to heroin and his fight to slay clean, she became intrigued by the idea of chronicling the life of the suburban heroin junkie.

She thought of Larry Clark, the gonzo photographer famous for his hyper-real, black-and-white pictures of street junkies in the 1960s and ’70s. Heroin, through Clark’s lens, was far from glamorous. Misty wanted to capture the same side of the suburban addict. But Clark had a key advantage. A junkie himself, he never had a problem with access. He simply photographed his surroundings. Misty, the product of a strict Baptist upbringing, has a history of substance abuse that can be recounted in the random night she’s consumed too much alcohol.

At Piano East, as kids began experimenting with drugs, Misty stayed straight, adhering to her practice of leaving parties the minute she caught a whiff of marijuana and parting ways with friends-like Jason-who didn’t just say no. Even now, at 21, Misty Keasler is the picture of Piano youth. (Rather, an outdated picture of Piano youth.)

SHE PARKED HER MAXIMA OUTSIDE MEDICAL CENTER OF PLANO and raced inside. Misty tried to imagine the strings Nelson pulled to get inside the E.R. “This kid’s parents are never going to let me take pictures of him,” she thought to herself. She pictured herself approaching the admitting nurse-at this hospital that averaged 10 heroin overdoses a month at the peak of the crisis-and asking for directions to the room occupied by the nameless junkie brought in earlier that afternoon: “Excuse me, where is the heroin overdose?” “Get oui of here!”

Misty managed to bypass the admitting nurse altogether. As she began wandering the hall, she found Belita Nelson sitting inside a dimly lit hospital room. She almost didn’t recognize the woman she affectionately calls “B”: Sitting in a chair, her legs folded close to her chest, Nelson rocked back and forth, her eyes fixed on the hospital bed where a motionless body lay wrapped in a blanket. Misty thought the person was dead.

“Start taking pictures,” Nelson said.

Misty didn’t ask questions. She didn’t ask who it was she was shooting or where the kid’s parents were. She didn’t bother with the model-release form sticking out of her bag. This was the picture she and Nelson had been talking about: the picture of a junkie this close to death-or beyond. She reconciled her own misgivings about being in this place, at this moment, documenting this image, remembering the advice of her photography teacher, Byrd Williams. Williams likened his student’s mission to that of a photojournalist documenting the ravages of war. It wasn’t her job to take sides; it was her job to cover the story. “Shoot now,” he was always telling her, “edit later.” So she did. She shot what she assumed was a heroin junkie, dead of an overdose, wrapped in a blanket that left only his feet exposed.

It was through her camera’s eye that she noticed something written across the bottom of the victim’s socks, a name perhaps. Jason’s name. And a six-digit number. “Why is that person wearing Jason’s socks?” she thought to herself, struggling to make sense of what she saw. “He must have left them here.” She continued to shoot, but refocused on the six-digit number. Those were the socks assigned Jason while he was in prison. The motionless body wrapped in a blanket was… Jason?

Misty let the camera drop from her eye. Her mind was racing. This couldn’t be Jason…. Jason was clean…. Jason was with her… last night… at the poetry jam… at Club Clean>iew…. This couldn’t be Jason…. Jason was clean…. Misty began shaking.

Until that moment Nelson assumed Misty knew the addict was Jason. After all. the two of them had been spending virtually all of their free time together indeed, they had been together until 3 that morning. But the look on Misty’s face told her otherwise: her son’s closest friend was as stunned by Jason’s free fall as she was.

“It’s OK,” Nelson said. “He’s going to make it. Keep shooting.”

“What if he doesn’t want me to take his picture?”

“Too bad,” said Nelson, who had confronted her son’s mortality on two other occasions. “We’re doing it my way this time.”

IF PLANO WERE A LITTLE ROUGHER AND A LOT POORER, MAYBE NO one would’ve been surprised by that first Piano-related heroin death four years ago.

This kind of thing wasn’t supposed to happen in Piano. Strict planning and zoning codes transformed the one-time farming community in the northern shadow of Dallas into a real-life Utopia, a young, well-educated place with Mayberry values and Leave It to Beaver morals. A place where the median household income hovers around $60,000 a year, where the average head of that median household is a 35-year-old with kids who attend schools that are academically acclaimed and regularly win state athletic championships. A place with well-tended public parks and hike-and-bike trails built within walking distance of the average home. A place, in short, where above-average is the average.

The National Civic League even tagged Piano an all-American city. But that was 1994. two years before detectives working the burglary unit at the Piano Police Department began noticing some changes. An increasing number of break-ins were taking place in the mid-die of the day. and the suspects were addicts who had begun stealing in order to support their drug habit. Not coincidentally, the town with Mayberry values and Leave It to Beaver morals lost four to heroin that year ( 17-year-old Jason Blair, 19-year-old Adam Goforth. 20-year-old Jeff Potter, and 22-year-old Matt Shaunfield).

And yet Piano refused to believe the deaths were anything more than an aberration, until the end of 1997 after a string of 1 i Piano-related heroin deaths captured national headlines and brought the death toll up to 15. Only then did Piano, Texas -the town Money magazine once called the safest city of its size in the country-snap out of its denial. More than 3.000 Americans a year were dying from heroin overdoses, an estimated 24 to 30 of them in Dallas County, but the national spotlight was fixed on the one-time farming community named by al9th century settler who thought “Piano” was the Spanish word for “plain.”

As it turns out. Piano typifies the new heroin culture. In the mid-’90s, Mexican and Columbian drug cartels began targeting the suburbs for the same reason anybody with a product to sell targets the suburbs: a willing customer base, plenty of disposable income, and an overall lack of regulation (a police force more accustomed to garage break-ins than drug dealers). To complicate the equation, the product was new and improved: purer (40 percent purer than it was in the ’70s and ’80s) and available in a powder that’s as easy to snort as cocaine. “Dealers take black tar heroin, freeze it. then grind it up in a coffee grinder, and mix it with an over-the-counter sleeping aid that has an antihistamine in it that keeps your nose from running.” says Greg Rushin, Piano’s assistant chief of police. In what appeared to be an especially perverse marketing ploy. Piano drug dealers weren’t even calling it heroin. “They called it chiva.” says Rushin. “There was great naivete. Some of the kids didn’t think it would be as addictive if you snorted it, which isn’t true.” In a suburban community like Piano, where kids are basically clean, high-grade heroin (sold for $5 to $15 a hit) can cause death immediately.

As the death toll climbed. Piano police launched what was dubbed “Operation Chiva”: they tripled the number of officers assigned to the department’s narcotics division from four to 12; they created the Heroin Task Force (in conjunction with the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Texas Department of Public Safety, among others) to target the dealers; and they began coordinated aggressive prosecution, treating each overdose as a crime, rather than an accidental death. In July ’98 “Operation Chiva” led to the indictment of 29 people who were accused of conspiring to distribute heroin and cocaine in the Piano area and contributing to Piano heroin overdoses. Of the 29 all but one were convicted or pleaded guilty. The 18 months since have seen a drop in drug overdoses, according to Rushin. “The thing that really helped is the broad-based community effort, getting everybody-press, clergy, legislators, individual families-to work together. Nobody can do it alone.”

Misty Keasler was a sophomore at DePaul when her home-town began making the evening news. She had grown accustomed to the blank stare she received whenever she answered the question, “Where are you from?” But now that had changed. Piano was suddenly part of the national lexicon. To hear newscasters tell it. heroin was killing off young people in Piano.

She missed the broadcast of an interview with an imprisoned addict from Piano whose mother was so desperate to get him off the streets she had him arrested for possession of heroin. But Misty”s mother saw it and promptly telephoned her daughter: her old friend Jason-with whom Misty had spent countless weekends on a bus traveling to speech tournaments around the state-had been interviewed. Misty knew Jason experimented with drugs in high school; in fact, that’s the reason they’d grown apart. Still, Misty was stunned by her mother’s phone call.

She was back home in Richardson, living with her parents and attending Collin County Community College, when she caught up with Jason last spring. Out of prison and living with his mother, Jason was in the process of rebuilding his life when he and Misty became friends again.

It was at the beginning of the summer that Misty and Jason sat at Belita Nelson’s kitchen table discussing with her the possibility of photographing heroin junkies for Misty’s second photo documentary. Although Nelson believed it would be dangerous, she also saw the project as an opportunity to show that the heroin crisis was ongoing and not at all a thing of the past.

Sitting there at his mother’s kitchen table, six months after his release from prison, Jason knew better. Only weeks before, on his 21st birthday, Jason had relapsed.

THEY HAD JUST SCORED. NOW THEY NEEDED A PLACE TO SHOOT UP. Too early to hit the clubs in Deep Ellum, they drove to Oak Cliff and a certain gas station favored for its habit of leaving the restrooms unlocked. Walking from the car to the men’s room, they made an interesting threesome: the girl with the pierced lip: the twentysomething guy in full makeup; the conservatively dressed young woman with a camera hanging from her neck.

Inside a men’s room just large enough to accommodate the three of them, one junkie shot a needle into the arm of the other, as Misty Keasler took pictures. Curiously,despite the purity of today’s heroin. all of Misty’s subjects preferred shooting up to snorting. It was a surreal moment-to anyone but the three crammed inside the restroom. In the two and a half months since she found Jason wrapped in a blanket at Piano Medical Center. Misty has thrust herself into the nether world of the Piano heroin crisis. Her life revolves around a part-time job. classes at Collin County Community College-and drug runs with heroin junkies. (If her friends from Piano East could see her now.)

Sitting outside the commons at CCCC waiting for the results of the night in Oak Cliff to dry in the photo lab. Misty digs through her oversized black shoulder bag. “The camera protects me from seeing what’s really going on-big time-until I look at the negatives, and then it’s more of a job,” she says. preoccupied by her search. ’if they’re shooting up and I’m out of him, all of a sudden it’s this scary thing. When I have my camera and I’m shooting pictures, it’s about the pictures.” She is still digging. “Here they are.” she says, pulling a pack of cigarettes from her bag. “I started smoking just to calm my nerves.” As she attempts to light a clove cigarette on what is an uncommonly windy day, she is both self-deprecating and self-conscious. After four attempts, she finally succeeds. But, the irony of Misty Keasler smoking a cigarette of any kind isn’t lost on her. This is the person who quickly amended her answer of “No” to the question “Did you drink in high school?” with “I would occasionally drink wine with my boyfriend, but my parents still don’t know about it.”

With Jason enrolled in a California rehab called Sober Living by the Sea and studying to become a drug and alcohol counselor. Misty thinks back on the all-night telephone conversations she used to have with Jason before his relapse sent him far from home. Now she realizes how naive she was about his battle with heroin. “I got into this and 1 thought. ’Junkies are bad.’ Very black and white,” she says. “Now the lines aren’t as clear. It’s like the deeper you get into it. the lines start to dissolve.”

She has plenty of pictures of junkies scoring and shooting up. What she lacked, until recently, was the footnote to her series, her Leave It to Beaver moral. After weeks of discussion with the Collin County medical examiner, she was finally granted access inside the morgue. The night after she heard about a Piano Senior High graduate (class of 95) who died of a heroin overdose in Mexico, she had a dream. In the dream the coroner approached her as she stood in the morgue and said that yes. she could take pictures of the corpses – the cold, stiff, yellow bodies-but first she must lie down with them. In order to get the pictures of heroin junkies this close to death, she had to lie down with them. She woke up in a cold sweat.

Three weeks later, as she stood inside a refrigerated room at the Collin County morgue, she photographed the body of on 18-year-old girl. dead of a heroin overdose. There were two tags around her toes and a tag around her wrist.

Misty Keasler had never tried heroin and yet the drug had robbed her of her innocence, “I’m so much street smarter,” she says. She is the picture of Piano youth.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain