THE MORNING OF FRIDAY, April 18,1997, Daniel Wells of McKinney took the stand in his own defense. Charged with aggravated sexual assault for fondling his girlfriend’s 8-year-old daughter, Wells explained it was all a misunderstanding. Wells was a decorated Vietnam war hero, with two Purple Hearts and two Bronze Medals for valor. On cross-examination, testimony revealed that even the mother initially hadn’t believed the little girl. Il was the war hero’s word against the child’s. In desperation the prosecutor’s office tracked down B.G. Burkett, a silver-haired Dallas financial adviser who has obtained a national reputation as a military researcher and historian of the Vietnam War. Within an hour, Burkett had obtained Wells’ military record. That afternoon, Burkett drove to McKinney, was swom in as an expert witness, and testified that Daniel Wells was a fake. He had a mediocre military career as a Navy cargo handler; he had never served in combat, nor had he ever received any valorous decorations. Wells’ story fell apart. He was sentenced to 20 years.

Like the nationally infamous Larry Lawrence, the big Democratic donor who invented a story of heroic action in the merchant marine and was briefly interred in Arlington National Cemetery, Daniel Wells had concocted his Vietnam war stories from true-life accounts in books and magazine articles.

Wells’ lies were no surprise to B.G. Burkett. Whenever a media story portrays a troubled Vietnam vet who relies on the war to explain or excuse himself, Burkett investigates. In most cases, the purported vet is an exag-gerator or an outright fake.

For the last decade, Burkett, now 54, has undertaken a one-man crusade to advance the truth about the men who fought in Vietnam and to expose the frauds who have played on the image of Vietnam vets as homeless, unemployable, suicidal, or addicted. Burkett, a graduate of Vanderbilt and the University of Tennessee, served as an ordnance officer with the 199th Light Infantry in 1968-1969. Burkett’s mission began in 1986 when he agreed to serve as co-chairman of the effort to build the Texas Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Fair Park. (President George Bush was the honorary chairman.)

Repeatedly, Burkett tried to interest reporters in writing about the memorial only to be asked instead about homeless veterans and drug abuse rates. Time and again he made fund-raising calls to Dallas’ corporate leaders and philanthropists, only to be rebuffed. After doing some research, Burkett realized that what everyone thought they “knew” about Vietnam veterans was wrong.

The fact is, Vietnam veterans-real Vietnam veterans-are among the most successful generation of warriors in the nation’s history. The popular image of the permanently traumatized Vietnam vet, perpetuated by fakes adept at capitalizing on the public image, is so wrong that it almost amounts to a parody.

Determined to set the record straight, Burkett became a detective of sorts. Whenever he saw someone in the newspaper or on TV described as a Vietnam veteran, Burkett filed a Freedom of Information Act request for his or her military record. Most often he checked the “image makers,” the veterans used by reporters to illustrate stories on homelessness. Agent Orange illnesses, criminality, drug abuse, or alcoholism.

Burkett has filed FOIA requests for more than 1.700 individuals in the last decade, and more often than not, the records revealed that the “veteran” was bogus. Those claiming to be involved in covert operations or members of elite military groups like the Navy SEALs or Green Berets were even more likely to be impostors. Some of the phonies had built elaborate frauds, going to extraordinary lengths to forge and steal documents and photographs, then altering them to support their pretensions to heroism. They bought medals at flea markets and through catalogs. They cried on camera when talking about their dead buddies, about witnessing atrocities. Some had fooled their families, their wives, fellow workers, psychiatrists, even military commanders who had also been in Vietnam.

In the process, Burkett also uncovered a much larger story, an immense public fraud almost completely overlooked by the press and historians and other alleged experts on the Vietnam War. Those who fought it were neither particularly young nor disadvantaged nor overwhelmingly black or brown, nor apt to abuse drugs in the jungle or to return home as emotionally devastated misfits. Just the opposite, in fact, has been (he case. Vietnam vets have fared as well or better than any other generation of warriors and continue to make important, positive contributions to the nation. In effect, they have been slandered. Burkett’s massive investigations reveal a silent conspiracy among both individuals and institutions eager to advance their various agendas and indifferent to the truth, which long since became the first casualty of the Vietnam War.

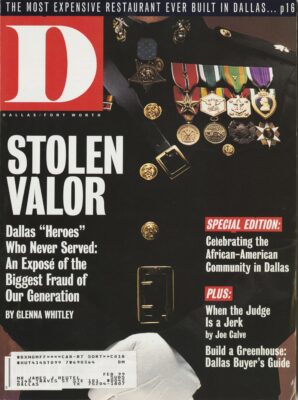

Now, Burkett and 1 have co-authored what amounts to a comprehensive indictment of this fraud: Stolen Valor: How the Vietnam Generation was Robbed of Us Heroes and History, a book that is certain to provoke controversy and redress decades-old wrongs that have tainted society’s view of Vietnam vets.

Burkett’s research began in Dallas, but he soon uncovered phonies who had deceived the nation’s most prestigious news organizations. For example, the murderer who snookered the Boston Globe and Mike Wallace of “60 Minutes” and wrangled early release from prison because his heroin addiction was supposedly caused by war trauma suffered in Vietnam. Or the bogus SEAL who pulled the wool over Dan Rather’s eyes and became the centerpiece of an award-winning CBS documentary on the Vietnam War. And the phony Green Beret who testified before a federal judge against members of a Mafia family.

Burkett’s expertise in Vietnam-era military records has often embarrassed the news media. In March of this year, when self-styled “Vietnam vet” and “Navy SEAL” Jason Leigh seized a VA building in Waco in a 14-hour stand-off with police, national network news reporters were quick to identify him as a Vietnam veteran and Navy SEAL. Like so many times before, Burkett quickly proved Leigh was a phony; he had been released from the military after only five months and had never served in Vietnam. But to Burkett he was only one more in a long string of those who would like us to believe their problems began in Vietnam.

Phonies and Frauds

When Burkett first began to investigate his suspicion that fakes were trading on Vietnam stereotypes, Dallas provided plenty of examples.

■ Former Green Beret Jesse Duckworth was a common sight at Dallas-area veterans events in the mid-’80s. Slovenly in dress, he stank of alcohol and always needed a shave. He frequently bragged that he had been awarded the Silver Star for combat heroism.

Photographers gravitated to Duckworth at parades and wreath-laying ceremonies. Journalists asked him for quotes. On Veterans’ Day 1986, an Associated Press picture of Duckworth saluting a pair of jungle boots at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the Washington Mall appeared in newspapers across the country with captions such as: “Vietnam veteran salutes war dead.”

But Duckworth had never been a Green Beret. He was awarded no medals for heroism. And he had not served in Vietnam.

J.W. Duckworth had been a private first class in the Army, and his only overseas duty was in Germany. Court-martialed while at Fort Hood on two charges of AWOL, Duckworth had been sentenced to 40 days hard labor and reduced to private E-1 before being discharged.

■ Joe Testa was president of the Dallas Vietnam Veterans of America chapter in the mid-’80s and often donned old combat fatigues for events where cameras might be present. Testa claimed he had been drafted in 1967 and had served 18 months with an infantry division headquartered west of Saigon. When Oliver Stone’s movie Born On The Fourth of July was being filmed in Dallas. Testa appeared at calls for extras, wearing a Silver Star and walking with the help of a cane, as if suffering from an old war wound. Reporters often turned to Testa when they wanted to write about veterans and Agent Orange, mental illness, drug abuse, or homelessness.

But Testa had not been drafted, He enlisted in the Army in 1967. After going AWOL twice, he received court-martial sentences totaling nine months of hard labor. Testa did not serve in Vietnam, received no Silver Star or anything close to it, and was discharged under conditions “other than honorable.”

■ In July 1989, the Dallas Times Herald reported that Vietnam veterans Gaylord Stevens and Ken Bonner had opened a Vietnam War Museum at the Alamo Plaza in San Antonio, the only museum of its kind in the country. The two men organized volunteers to solicit money on the street-wearing ragged military garb, of course. Stevens, the director, was gaunt and bearded, seemingly hardened by his service as an elite Navy SEAL in Vietnam during 1968-1969. Co-founder Bonner had served in the Green Berets in 1971-1972. Both gave the Herald their discharge papers to authenticate their war service.

But both were impostors. Stevens had not been a SEAL; he had served in the Coast Guard on stateside duty from 1969 to 1972. Bonner hadn’t entered the Army until 1978, three years after the war ended, and had never been a Green Beret. He had, however, taken the precaution of adding seven years to his reported age in order to seem old enough to have served in Vietnam

■ While an inmate in federal prison in Texarkana on drug and firearms charges during the 1980s, John Woods founded the first “incarcerated” chapter in Texas of the Vietnam Veterans of America. After his release from prison. Woods became an outspoken advocate for troubled Vietnam veterans who had been driven into crime by war-related problems. He testified on their behalf before the U.S. Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee and the U.S. House of Representatives, telling how wartime traumas led to crime. Woods’ own problems, he told people, had been triggered by his experiences as a secret assassin in Vietnam.

In 1988, Woods was appointed executive director of the Vietnam Veterans Resource & Service Center in Dallas to help veterans obtain VA benefits and services. A story about Woods in The Dallas Morning News called him a “ballpoint guerrilla,” a “point man in near-daily firefights,” the “Vietnam Veterans of America’s answer to Rambo in Texas.”

“His motivation comes from personal experience,” wrote reporter Steve Levin. “Foui times, he has had surgery to remove tumors he believes are related to his exposure to the defoliant Agent Orange in South Vietnam as a member of the Coast Guard.”

But John Woods served in the Coast Guard as a seaman apprentice for only one year, from October 1970 to October 1971, and that service was entirely in American waters, The closest he came to the Vietnam War was a short cruise to Honolulu. Though Woods signed up for a four-year tour, he was discharged early, declared “unsuitable for military service” after repeated abuse of drugs aboard the Coast Guard cutter Mellon.

In his one year of active duty. Woods progressed from smoking marijuana to taking heroin, suffering three separate drug overdoses. After he left the service. Woods had been arrested at least a dozen times and convicted of three felonies. Burkett showed the record to a Dallas Morning News reporter, who wrote a copyrighted story in the paper exposing Woods. After lis exposure, four members of the center’s board of directors resigned, including Howard Swindle, an assistant managing edi-or of The Dallas Morning News.

Incredibly, the Texas VVA decided to ignore Woods’ lies, apparently because he had not falsified his record to obtain employment or government benefits. In the ultimate irony, Woods was elected president of the Dallas VVA Chapter and for a ceremony on Memorial Day in 1994 played host to General Westmoreland. Today, he is employed by the national VVA organization and has continued to insist he suffers tumors caused by exposure to Agent Orange.

■ Retired Lt. Colonel Michael Donley was well-known among his colleagues as a Vietnam War hero who was still struggling to put the horrors of combat behind him. His first day in-country, Donley was ordered to lead the rescue of a downed Huey transport helicopter in the Delta region. “By the time we’d gotten there,” he told a reporter, “VC had overrun the position. and our job really became retrieving the bodies.” A few months later, he was again aboard a Huey, this time on a classified mission. When Donley was shot in the leg, his sergeant threw him over his shoulder and carried him 200 yards to cover. Treated in Japan, Donley was sent back into combat and later shot in the same leg. Two Purple Hearts to his credit, he was sent home where he retired from the military as a lieutenant colonel.

But Donley struggled with war memories, waking in the night with the memories of the stench of burning bodies, the sounds of screaming. The internal pressures cost him two marriages. Elected first vice president of the Dallas-area NAACP, Donley told friends he used religion and the teachings of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X to overcome the trauma the war caused in his life.

But military records show Donley was stationed at Webb Air Force Base during his tour of duty-as an inventory management specialist. In other words, during the Vietnam War, he was an enlisted supply clerk in Texas.

■ During his campaign for the Addison City Council in 1991, Archie “Bud” Akin boasted that he had served as a lieutenant in Vietnam and piloted A-4 Skyhawks for five years in the U.S. Navy, an important qualification in a town whose chief asset is its corporate airport. Akin was duly elected. But after being accused of “meddling” in an important lawsuit against the city, hiring friends for contracts, and wasting city funds, Akin became the target of a recall campaign.

That’s when voters discovered that Akin had never served in Vietnam. Although he had joined the Navy at age 17 in I960, he had never come close to piloting Navy Skyhawks.

■ When private investigator James Joseph Young Jr. went into business in Dallas, he made much of his experiences as a Special Forces colonel who saw combat in three wars-World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. He used the title “Retired Colonel” and scattered military memorabilia throughout his office. Young proudly talked about his experiences in covert operations and his many decorations, which included the Distinguished Service Cross, two Purple Hearts, and more than 50 commendations from the Army. But the “retired colonel” had served only in WWII, and then his highest rank was private first class. Young’s fabrications were exposed in a bizarre way, by a true hero.

In 1987, Young was hired by Dallas developer Robert Edel-man to kill his estranged wife. Young turned to an acquaintance, the late Fred William Zabitosky, to help him find a hit man. As a Green Beret in Vietnam, Zabitosky was assistant team leader of a nine-man Special Forces recon team. The group was operating deep within enemy territory on Feb. 19, 1968, when a larger NVA force attacked. Though seriously wounded himself, Zabitosky rescued the injured pilot from a burning helicopter while under heavy enemy fire. He received the Medal of Honor for his heroism.

When approached by Young, Zabitosky immediately contacted the FBI. He cooperated with federal agents by setting up a sting, telling Young he wasn’t interested but that he could find someone who was. Taped by Zabitosky talking about the hit, Young ultimately pleaded guilty to his involvement in the proposed murder-for-hire and went to prison.

■ One night in 1988, a social worker named Keith Roberts invited a pretty young woman whom he had treated for depression at a Dallas-area psychiatric hospital to meet htm at a local hotel. At the hotel, Roberts tied her up and slipped a black leather hood over her head and a red dog collar around her neck and attached a leash to it. While forcing himself on her, Roberts told her he had been part of an assassination team in Vietnam, highly trained men who infiltrated villages at night and slit civilians’ throats. The grisly story terrified the young woman. Roberts’ message was clear: Tell and you’re dead.

Roberts used the story not just in bizarre seduction ploys. He told others around the hospital the same wild stories of assassinating civilians in Vietnam. But as Christine Wicker reported in The Dallas Morning News, the truth came out when the young woman filed a personal injury lawsuit against Roberts and the hospital where he worked: The social worker had never served in Vietnam. The patient was awarded $1.1 million.

■ “Vietnam vet” Scott Barnes, an Arizona dress-shop owner, told lies that possibly changed the course of American history. In May 1992, Ross Perot. Dallas’ very own populist billionaire, was racking up a commanding 37 percent in presidential polls. But when Barnes, who had somehow managed to get Perot’s ear, told the independent candidate he had been hired by the Republicans to tap Perot’s phones, smear his daughter Carolyn, and disrupt her August wedding, Perot called off his campaign.

That was just one of many bizarre events in the topsy-turvy world inhabited by Barnes. In 1985, ABC News bought Barnes’ assertion that he had been hired by the CIA to assassinate a Honolulu businessman; the network later was forced to retract the story.

A self-described former intelligence operative, Bames over the years has claimed to have been an Army MP, a Navy SEAL, a Green Beret, a CIA assassin, and a DEA agent. He is best known for contacting POW-MIA groups, claiming sightings and escapes of men still missing in Vietnam, and asking for money and other help to stage rescue attempts. That’s apparently how he first met Perot, whose interest in the POW issue he adroitly played on.

But military records show Barnes was never involved in Special Forces or intelligence operations, nor did he ever serve in Vietnam. In reality, Barnes’ sole military experience was as a low-level security guard in a detention facility at Fort Lewis, Wash. Apparently, he failed even at that. Barnes was discharged 16 months after his enlistment for “failure to meet acceptable standards for continued military service.”

A Myth Contradicted By Fact

The myth of the Vietnam veteran as a social misfit, Burkett believes, has been perpetuated by the liars and wannabes who have seized on Vietnam either as an excuse for their problems or as a way to add color to their otherwise drab lives. In their efforts, the fakers have been aided and abetted by the VA, veterans advocates, and the mental health care industry. Not only do they denigrate fighting men who were among the finest America ever produced, but the monetary cost has been enormous for American taxpayers. Even today, the Veterans Administration often does not check the records of those who claim to suffer from maladies caused by Vietnam, even though it is patently clear from Burkett’s research that many of those who make the claims never came within spitting distance of Southeast Asia.

But the deeper harm may be to our understanding of our own history. The image of those who fought in Vietnam as poorly educated, reluctant draftees-predominantly poor whites and minorities-is not true.

■During the Vietnam War, seven million men volunteered for the military; only two million were drafted. Burkett’s research indicates that 75 percent of those who served in Vietnam itself were volunteers.

■They were the best educated and most egalitarian military force in America’s history. In WWII, only 45 percent of the troops had a high school diploma. During the Vietnam War, almost 80 percent of those who enlisted had high school diplomas, and the percentage was higher for draftees-even though, at the time, only 65 percent of military-age youths had a high school degree. Throughout the Vietnam era, the median education level of the enlisted man was about 13 years. Proportionately, three times as many college graduates served in Vietnam than in WWII.

■They were hardly teenagers, despite the common belief that youngsters were sent to Vietnam as cannon fodder. An analysis of data from the Department of Defense shows that the average age of the more than 58,000 men killed in Vietnam was almost 23 years old.

■The stereotype holds that those who died in Vietnam were disproportionately black and Hispanic. About five percent of those killed in action were identified as Hispanic and 12,5 percent were black-making both minorities slightly under-represented in their proportion of draft-age males in the national population. (When asked by Burkett, most people guess that “thousands” of 18-year-old black draftees died in Vietnam. In reality, only seven of the killed-in-action match that description.)

■Another common negative image of the soldier in Vietnam is that he smoked pot and shot up with heroin to dull the horrors of combat. However, except for the last couple of years of the war, drug usage among American troops in Vietnam was lower than for American troops stationed outside the war zone. And when drug abuse rates started to rise in 1971 and 1972, almost 90 percent of the men who fought in Vietnam had already come and gone. A study after the war showed the use of illegal drugs among those who went to war and those who stayed at home to be about the same.

■Of the 5,000 men who deserted the U.S. military for various causes during the 10 years of the war, only about 250 did so while attached to units in Vietnam. Only 24 deserters attributed their action to the desire to “avoid hazardous duty.” And 97 percent of Vietnam veterans received honorable discharges, exactly the same rate for the military in the peaceful 10 years prior to the war.

■ After the war ended, reports began to circulate of veterans so depraved from their war experiences that they turned to crime, with estimates of the number of incarcerated Vietnam veterans as high as one-quarter of the prison population. Bui these estimates relied on the self-reporting of criminals. In every major study of Vietnam veterans where military records were verified, a statistically insignificant number of prisoners were found to be Vietnam veterans.

■A corollary to the prison myth is the belief that substantial numbers of Vietnam veterans are unemployed. But a study by the Labor Department in 1994 showed that the unemployment rate for Vietnam veterans was 3.9 percent, significantly lower for male veterans of all eras (4.9 percent) and the overall unemployment rate for males (6 percent).

■Since the war, the stereotype of the homeless Vietnam vet has been buttressed by panhandlers with signs like “Vietnam Vet: Will Work for Food.” But the few studies using military records show that the percentage of Vietnam veterans among the homeless is very small.

■The same is true for the belief that Vietnam vets have high rates of suicide. More Vietnam veterans, it is often reported, have died by their own hand than did in combat. Not true. A 1988 study by the Centers for Disease Control found that the suicide rates of Vietnam veterans aren’t any different than those of the general population.

Contrary to these perceptions, Vietnam veterans as a group have higher achievement levels than their peers who did not serve in the military. Those who remained in uniform reshaped the American military after the Southeast Asian disaster and mobilized to win the Gulf War with lightning speed. Disproportionate numbers of Vietnam veterans-such as Dallas” own Sam Johnson and Arizona’s John McCain, both POWs- serve in Congress. Florida’s former congressman (and POW) Pete Peterson is now U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam. Vice President Al Gore is a Vietnam veteran, as is Gen. Colin Powell, former head of the joint chiefs of staff. Dallas City Manager John Ware is a Vietnam veteran, as is civic leader Roger Staubach, along with scores of our top corporate CEOs. The stereotypes may persist, but meanwhile, real Vietnam vets are helping to run the country.

Related Articles

D CEO Award Programs

Deadline Extended: D CEO’s Nonprofit and Corporate Citizenship Awards 2024

Categories include Outstanding Innovation, Social Enterprise, Volunteer of the Year, Nonprofit Team of the Year, Corporate Leadership Excellence, and more. Get your nominations in by April 19.

By D CEO Staff

Local News

Texas Lawmakers Look to Take Zoning Changes Out of Dallas’ Hands

Dallas is taking resident input on its ForwardDallas land use plan, and a vocal group is leading the opposition. But new talk among conservative Texas policy makers indicates the decision might not be in the city's hands for long.

Healthcare

Convicted Dallas Anesthesiologist Could Face 190 Years for “Toxic Cocktails” in IV Bags

Dr. Raynaldo Ortiz worked at the Baylor Scott & White Health facility after spending time in jail for shooting a dog and while having a suspended medical license.

By Will Maddox