AT 8 P.M. ON JAN. 10. DALLAS POLICE SPOKESMAN ED Spencer strode to the podium of the spartan 30-by-40-foot third-floor room that serves as the site of press conferences at police headquarters. Barely glancing at the horseshoe of cameras before him. Spencer cleared his throat and read the statement police had spent the past three hours preparing: “On Dec. 29. 1996. the Dallas Police Department initiated an intensive investigation into allegations of sexual assault against two members of the Dallas Cowboys and a third individual. Through the investigation process, we have determined conclusively that the allegations are not true and that a sexual assault did not take place.”

Asplit-second before Spencer began. 37-year-old Marty Griffin. the KXAS Channel 5 investigative reporter who had broken the Story of the “rape.” slipped into the doorway of the crowded room. Clad in an oversized varsity jacket, clutching his microphone as a kid might a toy. the normally cocksure Griffin looked small, quiet and badly shaken.

Ten days earlier, at the news conference police held to announce Erik Williams and another Cowboys player, later identified as Michael Irvin. were under investigation, a different, more familiar Griffin had been present. That Marty was the combative, self-assured Channel 5 “Public Defender.” the man who had scooped other journalists in the Michael lrvin sex. drugs and murder-for-hire scandal. But this Marty, slinking through the doorway, looked as if he’d been dragged from the nearest pub. where he’d been washing down MI let of crow.

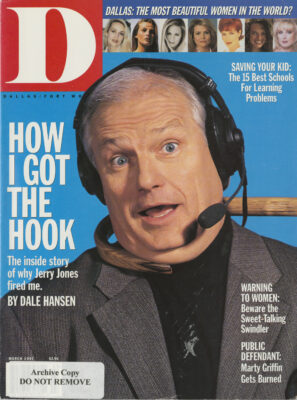

In 11 days, what might have been the biggest story of his career had crumbled. Speculation ran rampant. Had Marty set himself up, the easy mark of some hasty cops, a topless dancer and his own blinding ambition? Or did he conspire with his sources- as a lawsuit would later allege-to perpetrate a con on the Cowboys and the public? In an odd reversal of fortune, Marty would become the investigated rather than the investigator. The squalid episode needed a scapegoat-and who better than Marty Griffin?

IN BROADCAST NEWS J AMES BROOKS’ 1987MOVIE ABOUT love and declining standards in network news, the producer, played by Holly Hunter, takes a crew into the Central American jungle to film peasant rebels. Her cameraman asks one soldier to put on the new boots Uncle Sam has just delivered in lieu of badly needed weapons. “Stop,” yells Hunter as the camera man n^V crouches for the shot. “Just do what you want, sir,” she tells the bewildered soldier, who puts on the boots anyway.

Today, Hunter’s character wouldn’t bat an eye at such efforts to help the news along. During the past 10 years, the line between reporting the facts and staging them has blurred still more. Gone are the godfathers of truth and accuracy, Walter Cronkite and Chet Huntley, replaced by shows I ike “Inside Edition” and “Hard Copy.” With their proliferation, the Darwinian struggle for ratings has become all-consuming, and the temptation to give the news alittle tweak nigh irresistible. After all, gas tanks don’t always explode on cue.

Enter Marty Griffin, a brash young reporter who had been struggling to make his mark on TV news since 1988, when he was hired at Channel 5, the perennial No. 2 station in this media market. Marty had grown up in Pittsburgh, the second of five children born to an inner-city Italian Catholic family. A self-described “wild guy” who was “always in trouble,” he was picked up at 15 for car theft. Fortunately for him, the charges were dropped.

Griffin believes the experience helps him gain the trust of sources to whom rivals cannot relate. “It’s part of the reason I can talk to people whose backgrounds aren’t the greatest,” he says.

Scared straight, he went on to Ohio University, where he discovered journalism. Although he searched for a news job out of college, his tapes were uniformly rejected, so he waited tables at a famous Pittsburgh steak joint. Eventually, he got a call from a Wichita Falls station that needed a weekend meteorologist. Just in time, too; Griffin says he set a customer’s jacket afire.

During his two and a half years in Wichita Falls, he became famed for his on-the-air antics, like slapping on a fedora and raincoat and belting out “Singin’ In The Rain” during a weather report. He moved to stations in Tulsa and Oklahoma City before reaching Dallas. Along the way, he switched from weather to weekend anchoring and police reporting. Channel 5 made him an investigative reporter, a specialty that suited his street-smart persona.

In the early ’90s, Griffin became one of the station’s “Public Defenders,” a new breed of muckraker who delved into everything from local corruption to odometer tampering. Often, the content was paper-thin, their importance hyped by campy commercials featuring reporters in trench coats emerging from shadow.

Griffin carefully cultivated his sources. “My sources are my career. I never hurt my family, and I never burn a source.”

In a market dominated by Channel 8’s conservative stable of reporters, it was hard not to notice Griffin. Dark and dapper in Armani suits, he had attitude. But his over-dramatic delivery of puffed-up facts earned him the moniker “No Facts” Griffin.

“I think he’s a well-meaning guy,” says John Miller, news director for Channel 8. “But he’s naive and not the brightest fellow.”

In one report, according to The Wall Street Journal, Grifrin used hidden cameras to catch operators for Dallas’ 911 system sleeping on the job. The city complained, saying they were not emergency operators but those who answer calls for dogcatchers and maintenance workers. “There’s a danger in investigative reporting when you get into a mind-frame where you disregard that which doesn’t prove your theorem,” Miller says, “when you want to get someone so badly that you ignore stuff that does not fit.”

The “Public Defender” team became the station’s most recognizable franchise, “They must have put incredible pressure on him to turn stories,” says Miller. “Last November [during sweeps], almost everything you saw was a ’Public Defender’ report. They [Channel 5 managers] considered it a major part of their image. They devoted about half of their image promotion to it.”

Grifrin shed the “NoFacts” nickname forever after Michael lrvin was caught last March in Residence Inn Room 624 with two topless dancers, illegal drugs and an array of sex toys. From the start, Griffin had the story by the throat. Not only was his reporting accurate, it was first-and being first is what counts in TV news.

The Pedini Affair is a case in point. In 1993. Dennis Pedini, a “covert surveillance expert,” met Griffin, who was covering the FBI siege of the Branch Davidians in Waco. Shortly after the lrvin story broke, Pedini, who’d since done work at Valley Ranch, called Griffin. The night before.Pedini claimed, he had been on a cocaine-buying expedition with lrvin, who at the time was loudly proclaiming his innocence and maneuvering to avoid indictment.

Griffin huddled with his editors, who said they wouldn’t run with the story without videotaped proof. So, with Pedini’s help, he got it. The “Tarnished Star” series catapulted Channel 5 into first place during its sweeps week run in May.

Although the episode did much to enhance Griffin’s reputation, it also left him with an ethical black eye, thanks to his reliance on a hidden camera and his insistence the station pay Pedini $5,000. The story became a public relations nightmare for the station, which was accused of checkbook journalism. Griffin remained undaunted. “The flip side is 1 got hundreds of calls,” he says. One of them was from a young woman named Nina Shahravan.

In late October, Shahravan called Channel 5, claiming to be a friend of lrvin’s. She suggested that lrvin needed help with a continuing drug problem. The desk passed the message on to Griffin, who returned Shahravan’s call.

Shahravan told Griffin she had been a topless dancer but had gotten out of the business. She said she didn’t smoke, do drugs, or drink, but nevertheless claimed she prowled the town with lrvin. Lately, Shahravan said, many things had happened to scare her. The night before, she said, lrvin had dropped acid (a claim that has never been confimed).

Griffin contacted a courthouse source, who told him that the Dallas County Probation office does not screen probationers for LSD. Then he talked to Pedini, who said he had seen Shahravan in Irvin’s company at the infamous “white house,” where some Dallas Cowboys players brought women to party.

On Oct. 30. Griffin met the petite Shahravan when she agreed to visit Channel 5 to tape an interview. Shahravan told him a tale of Cowboys parties and bizarre sex. But the biggest bombshell was Shahravan’s claim that she knew about Cowboys players dealing drugs.

TO FOLLOW UP ON SHAHRAVAN’s CHARGES, IN EARLY November Griffin contacted Herbert “Kim” Sanders, a 22-year veteran Dallas police officer with whom Griffin previously had worked on stories. He invited Sanders and other members of the DEA drug task force to come to the station and view the tape of Shahravan talking about her involvement with allas Cowboys players and drugs.

“Griffin wanted to know what we thought,” says another officer who watched the videotape. “A lot of the stuff she was talking about was just weird. Not illegal-just kinky. She did talk about possession. But mostly what we thought was there was no timetable and no corroborative evidence–just her word.”

Agents told Griffin they believed Shahravan because her information fit with other intelligence they’d gathered over the years. Sanders said he was interested in speaking with Shahravan. Around Thanksgiving, Griffin arranged a meeting for himself, Shahravan and Sanders at DEA headquarters. There. Shahravan told officers she had been asked to pick up a “Christmas package” for a player. She told officers she had seen large quantities of drugs at a condo where she was taken by limo to pick up the package. Assuming “the package” would contain drugs, she refused to pick it up.

“She kept saying she was scared,” one task force agent recalls. The agent says it was obvious she knew the players; the officers concluded that she was telling the truth. She provided a description and an address.

“You’ve got to be fairly smart to keep track of your lies,” the agent says, “and she’s just not that smart.” But there was no way to corroborate her story. “Mostly it was just stale-a party here two weeks ago, a party there,” he says. “We have to have it within 48 hours to do anything with it.”

The agents say Shahravan never asked for money. But after a while, they ended the interview. “It never got to the point where we ask why are you doing this-money or the good of mankind? And she kept saying she was scared,” the agent says. “So Kim told her ’Just don’t go back around these guys anymore.’ “

News executives at Channel 5 decided not to pursue the story. Sources close to the station say higher-ups flinched at the possibility of another hidden camera investigation. Their reputations had been sullied enough by the Pedini affair. And why dedicate the station’s resources to proving what seemed to be self-evident: that some Dallas Cowboys players had serious drug problems?

Griffin was in neither a position nor a mood to argue about the executive decision. On Dec. 17, 1996, he boarded a plane for a two-week vacation, believing that any story about Nina Shahravan and the Dallas Cowboys was dead.

GRIFFIN RETURNED TO DALLAS JUST AFTER NOON ON Monday, Dec. 30. He drove home from the airport and listened to his voice mail; among the messages was one from a hysterical Shahravan. When he returned her call, Shahravan, sobbing and obviously distraught, told him she had been raped the previ-I ous night by Erik Williams and another man while Michael Irvin held a gun to her head. Williams had recorded the whole thing on videotape. She didn’t know what to do. She couldn’t tell her boyfriend because he’d forbidden her to hang out with the players; she was too scared to tell her parents. She had no one to turn to but Marty.

Griffin first called Patsy Day at Victims Outreach, a crisis center he’d once featured in a story. When Day wasn ’ t there, he phoned detective Kim Sanders, whom Griffin figured would know what to do. Sanders was out most of the afternoon. When he finally got back to headquarters sometime after 6 p.m., Sanders told Griffin to have Shahravan contact him.

Sanders believed Shahravan had been traumatized by the incident; she was unable to follow his directions on how to get from Piano to Parkland Hospital. Eventually, Sanders told her to come to DEA headquarters. He and a DEA agent drove her to police headquarters, where rape detectives conducted an in-depth interview. She was then examined at Parkland. The detectives believed her story, persuaded, in part, by Shahravan’s vaginal abrasions.

Early the morning of Tuesday, Dec. 31, DPD’s top brass held a meeting. The decision was reached to search Williams’ home. At 4:55 a.m., a Collin County judge issued the search warrant.

At 5:45 a.m., Channel 5 received a call from a Dallas police sergeant: Police were running a search of Williams’ home. The bureau roused Griffin and a camera crew, who arrived at the house around 7:30-the same time police tipped off at least one other news organization. Police seized boxes of evidence, including 33 videotapes, baby oil, four guns and the green felt from the pool table where Shahravan said she had been raped.

An hour later, Dallas police paged Griffin again: Lt. David Goelden, a supervisor in me Crimes Against Persons (CAPERS) division, had volunteered to give Marty the first interview. “They got a hold of Marty around 8:30 and said, ’We’ll give you an exclusive,’ ” explains a Channel 5 source. “By the time he got down there, Channel 8 was there. But Goelden shooed them away and said, *I need to talk with Marty.’ So Marty and his cameraman go in and get the one-on-one interview with Goelden.” It was a game of mutual back scratching. Griffin gave the police Shahravan, and the police gave the reporter an hour jump on his competition. The scoop allowed police to claim that they were forced to call a press conference.

At 10:30 am, a grim Marty Griffin cut in to “The Maureen O’Boyle Show” over the “Public Defenders” logo. He described the events of the morning and concluded: “At this time, police tell me, that with the evidence they have, they are preparing warrants for the arrest of Erik Williams and another Dallas Cowboy.”

An hour later, Goelden held his own press conference at police headquarters. Although the police refused to release Shahravan’s name, saying she was tucked away in protective custody, they were more forthcoming with the names of the suspects. Contrary lo the DPD’s own written policy, Michael Irvin and Erik Williams were named targets of the investigation although no formal charges had been filed.

“You want a theory?” asks one of the lawyers for KX AS Channel 5. “I think the cops believed her story. And I think they got pissed because of the arrogance of these guys-the mink and the diamonds and the sunglasses and everything. They think they have them nailed and they want to the play the story up.”

And there was the matter of prior behavior. In 1995, Williams had been arrested and charged with sexually assaulting a 17-year old topless dancer under eerily similar circumstances, down to the body oil, the pool table and his penchant for sharing sexual escapades with his friends. A Collin County grand jury had no-billed Williams after the woman was paid a hefty out-of-court settlement in connection with her civil suit.

The initial press conference unleashed a media frenzy that had reporters nearly coming to blows. Not only were they galled at having to play catch-up with Marty, they were wondering exactly why he was so intimate with the facts of the case. Rumors were flying: Marty had tapes of the woman. Marty had footage of Cowboys snorting cocaine. Marty knew where police had hidden the woman.

During the first 10 days in January, Griffin repeatedly spoke to Shahravan at her secret hideaway and reported to viewers that she stood by her allegations and would testify in court if asked to. Griffin also reported that “sources” had told him that the police had enough evidence to arrest the men and Irvin’s voice could be heard on the videotape.

Dallas police didn’t deny Griffin’s involvement in the case, admitting the victim had made her outcry to the journalist rather than the police. “She called Marty, who she knew, and he called a DPD officer,” says another DPD spokesman, Sgt. Jim Chandler. Asked why the woman waited 24 hours before reporting the crime. Chandler responded, “Ask Marty.”

Hounded by his own peers, who demanded to know more about his role, Griffin behaved like many of the subjects in his own investigative pieces. He refused to answer questions, and when one reporter asked police about Marty’s relationship with Shahravan, Griffin called the question “irresponsible.” The rest of the media he simply accused of professional jealousy. “I kicked your ass. I kicked your ass,” he told Fox “I-Team” producer Kay Vinson. If Griffin was due a comeuppance, the pieces were all in place.

AS SOON AS THE STORY BROKE, IT BEGAN TO TAKE A dramatic twist. Irvin denied being anywhere near Williams’house on the night in question. Although credibility was, at best, suspect, his attorney, witnesses that he said supported Irvin’s innocence. More damaging still, Shahravan had alleged that both men used cocaine, but each had passed drug tests administered after the night of the alleged rape but prior to the playoff game against the Carolina Panthers.

Although news organizations initially are wary of reporting rape victims’ histories, journalists began scouring the city for information on the woman. They learned she was Iranian by birth, the daughter of a limo driver and sales clerk who live in Piano; that her first brush with the law came at 16, when she was picked up for shoplifting lingerie; that she dropped out of high school to marry; that she began to dance at second-tier topless clubs after she separated from her husband. Defense attorneys helped, providing police with the names of at least six other Cowboys who claimed they had been involved with Shahravan. The Dallas Morning News quoted her estranged husband as saying Shahravan had falsely accused him of rape. The portrait that emerged was that of a troubled young woman with a penchant for exaggeration.

The police began to publicly retreat from earlier statements; now, they said the investigation would be lengthy and that Irvin and Williams might never be questioned. Police said privately that they had found no physical evidence linking Irvin to the scene. Tests conducted on the felt from the pool table were negative.

Still, Marty Griffin stuck by his story and his source. But police began to hint that Griffin himself had played some unseemly part in the incident. Sgt. Ross Salverino, the CAPERS detective who oversaw the investigation, reportedly told defense attorneys that what disturbed him most about the case was that Marty seemed to have detailed knowledge of evidence even before CAPERS did. (Salverino denies that he made that statement,)

On Jan. 9, Collin County District Attorney, Tom O’Connell subpoenaed Marty Griffin, ordering him to turn over notes from his conversation with Shahravan on the day she made her first outcry. The next day, police brought Shahravan downtown, where Salverino and another officer confronted her with Irvin’s alibi, the absence of physical evidence, and each and every discrepancy they had discovered in her story. By the time they finished their interrogation, Shahravan had recanted.

What once seemed like the story that would make Griffin’s career now threatened to destroy it. On Jan. 10. DPD spokesman Spencer pointed an accusatory finger at Griffin, claiming police only released information about Shahravan’s charges “in response to media inquiries after a local station broke the story ” The police, defense attorneys, the media were all looking for a fail guy-and Griffin topped everyone’s list.

On Jan. 14, police formally charged Shahravan with filing a false report, which was later upgraded to perjury. She now claims she was coerced by the police to recant and stands by her original allegations.

Griffin came under aggressive attack from Irvin’s defense attorneys, who suggested that Griffin himself was under investigation. Attorney West went on the morning network news circuit, making loud noises about media misbehavior and going so far as to compare Irvin to Richard Jewell, the man who came under false suspicion of pipe-bombing the Olympics. West praised police and suggested that if anyone needed to fear lawsuits it was the media.

Erik Williams, however, was not nearly as laudatory of police tactics. On Feb. 12, he sued both the city of Dallas and the DPD. claiming that “in a shocking abuse of the public trust,” each had “eagerly participated in Shahravan and Griffin’s hoax.” He also sued Griffin and Channel 5 in a separate lawsuit.

After the debacle, the station had asked Frank Magid Associates of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to do some focus group research. The research showed that the audience was still mad at both Griffin and the station. Strangely, it also showed that Griffin’s was one of the most recognized names in local TV news.

After Shahravan retracted her accusations, and with Channel 5 up for sale, potentially to NBC, Griffin learned he would have nothing in the February “book” and, in fact, was told to take a month-long vacation. He declined. Although he continued to go to his office, he worked on no stories for the all-important sweeps week.

At a minimum, Griffin made errors in judgment. Fueled by ambition, temperament and the pressure to turn a story, Griffin abandoned his objectivity. Only weeks before the story exploded, Griffin scoffed at journalists putting on airs, “Objectivity is a journalism class myth,”

Griffin still has three years to go on a four-year contract. Sources close to him say he is interviewing for jobs in other cities, but taking a page from the subjects of his own investigations, he refuses to confirm or deny the rumor.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

Dallas College is Celebrating Student Work for Arts Month

The school will be providing students from a variety of programs a platform to share their work during its inaugural Design Week and a photography showcase at the Hilton Anatole.

By Austin Zook

Basketball

A Review of Some of the Shoes (And Performances) in Mavs-Clippers Game 1

An excuse to work out some feelings.

By Zac Crain

Home & Garden

Past in Present—A Professional Organizer Shows You How To Let Go

A guide to taming emotional clutter.

By Jessica Otte