THE MERCEDES-BENZES AND CADILLACS AND LEXUSES START rolling up an hour before the sale is to begin. At one point, four Rolls-Royces are parked in the lot; one blocks the alley and is later papered with traffic citations. The women, many in furs, queue up in front of Lou Lattimore, the gray store with the mansard roof that has come to represent sophistication in women’s fashion in Dallas. The ladies chat with each other, they edge toward the glass doors, they discuss their strategies. Where shall they head first? Try for a Maxima alligator handbag (normal retail price $3,875) or a Christian Lacroix evening bag ($950) or a Thierry Mugler suit ($2,185-$2,695) or a Ginochetti angora-cashmere blazer ($1,000)? Take 75 percent off, and they’re a steal.

The awful word that has drawn them here, the word that has no remorse, remains unspoken. Chapter 7 is something many people in Dallas know well.

Rather, talk here is of better days. One customer, Susan Nowlin, recalls how, soon after her marriage, she found two gorgeous outfits at Lou Lattimore and brought them home to show her husband. They chose one, and the next day she returned the second outfit to the store. Albert Lidji, the handsome, charismatic owner, told her how beautiful she had looked in both pieces. “I’ve discussed it with my husband,” she confided, “and I can only afford one.” Nowlin says, “Albert Lidji thought one moment and said, ’If I mark them both down 50 percent, would that help?’” To this day, when, judging from the length of her Mercedes, she no longer must choose between items, Susan Nowlin thinks about the generosity Albert Lidji showed her. She still puzzles over it. “My husband said it was a good business decision. . .” She looks up quizically. One can see that she wants to remember it as a gesture of the heart.

Another woman, who stands in line with her grown daughter, says, “Look at how the ladies in this line are dressed. No one dresses up like this for a garage sale at Neiman’s. They’re dressed up to show their respect for the store and for Albert Lidji.”

But as they jockey for position before the foyer that is still decorated for the Christmas season the store never celebrated, some of the women talk about a family feud, the loss of valued employees and a store that seemed to lose direction. Most probably are unaware of the accusations about missing merchandise and incompetence, allegations that have not only torn apart a once-close clan, but also doomed a store that was a benchmark for specialty retailing across the country and in Europe.

GOD GAVE ALBERT THE MAGNIFI-cent gift of incomparable taste, almost to the point of his being an artist,” says one of the family. “And God gave him great charm and a good heart, almost too good a heart.” (Family members talked for this story, but some requested anonymity for many of their comments; those who are estranged from Albert hope for reconciliation one day.)

Albert Lidji is known throughout the fashion industry as a man who promoted talented designers and sold their creations in a classy store that served wealthy, oft-photographed and well-traveled customers. Albert was the first to bring to Dallas such names as Donna Karan, Thierry Mugler, Franco Moschino and Jean-Paul Gaultier.

Albert formed lasting impressions on those with whom he did business. Paul Seidenberg, the owner of U.M.I., a clothing manufacturer in New York, sold garments to Albert for over 30 years. Albert, he says, “was and remains one of the finest gentlemen in our industry that ever was. He is the most charming of men, and a most-highly principled human being.”

To his customers, he was like a movie star they could talk to whenever they came into the shop. ’”Albert Lidji is like Maurice Chevalier.” says a former client. “He has a gorgeous French accent, and he is very handsome and he loves women.”

But Albert was not as interested in the nuts and bolts of business as he was in the beauty and glamour.

Says Paul Seidenberg: “His interest was in buying pretty things and selling them, not knowing or caring so much about it having to be paid for or when or stuff like that.”

An insider who worked closely with Albert puts it more bluntly. “I can almost say he does not know how to add two plus two.”

Jeffrey Weiss, one of several Dallas investors who hope to set Albert and his wife Martha up in a new shop in Dallas, says, “For Albert, it was a way of life, not the bottom line. It’s like Meyer Lansky said about Bugsy Seigel. He wasn’t interested in the money-it was making things.”

Albert was not a manager, but he was wise enough to employ people who had an interest in preserving the family investment. Until the final few years, his eldest sister’s husband, Armand Mires, was comptroller. Albert’s youngest brother, Henry, opened and closed the store every day, six days a week, and served as a general troubleshooter and manager. Betty, the wife of Albert’s other brother, later became a saleswoman.

Even so, the store suffered financially for many years-from delinquent accounts, overly-generous policies and shortages-missing merchandise. In the late ’70s, the shortages reached astonishing proportions, as high as $600,000 in one year, according to family members.

Losses were, in part, attributable to shoplifters, some of whom would layer garments on their bodies beneath oversized coats. “What were we supposed to do, run after them and ask them to take off their clothes?” asks Henry Lidji. Some other business owners would answer an emphatic yes. but not the Lidjis. They didn’t operate that way. They had grown up in a cultured environment and in a wealthy family. Chasing after thieves was not part of the picture for them.

Nor was urging clients with large outstanding bills to pay up. One woman owed $100,000; her husband finally came in and signed a note, then couldn’t pay it. Some women had buying sickness. After racking up big bills, they were afraid to tell their husbands. Some brought jewels in to offer as payment. Some purchased clothes while on a buying spree-leaving them behind for alteration, or for their maids to pick up- and then forgot about them. In one case a woman picked out more than $20,000 worth of clothing, charged it to her house account, then never brought it home. After the clothing had been held for several months, it was no longer salable, except on the discount racks. When the store finally sent a bill collector after her, she wrote a check for the entire amount, which the bill collector promptly ran off with. Everybody seemed to know the family was a soft touch.

Society ladies have been known to buy an expensive dress for an event, wear it and then return it. Many department stores do not accept returns on evening wear, but Lou Lattimore did. Marie Leavell, a competitor down the road, usually will not take returns. Says John Leavell, the owner: “The ladies who come in this store know there will be no funny ’bidness’ here.”

But, then again, sometimes generosity pays off. One woman, recently divorced, asked to be extended credit to buy a new wardrobe. Soon after, she remarried very well and not only repaid the debt but bought much more.

“My father always used to say,” Albert recalls, ” ’Albert is such a nice man, such a nice man, such a nice man, such a nice man.’ And through my life, I realize. I thought I had to be a nice man.”

And so he was. In good times, the losses were absorbed. But Albert never prepared for bad times. He didn’t save money. Everything went to good living, putting his children through school, providing generously for his family and siblings and investing the remaining money back in the store.

ALBERT LIDJI WAS BORN INTO RE-tail, in 1921. His mother’s family, French-speaking descendants of Turkish Jews who migrated to Egypt, owned a department store in Cairo, where Albert and his two brothers and two sisters grew up. At age 17, Albert told his uncle, who ran the store, that he wanted to open a women’s clothing department. At the time, the store sold furniture, silver, lighting and so forth, but no fashion. His uncle asked him his plans. Albert explains: “I said ’I want to take the first floor, remodel it and put in ready-to-wear.’ I said ’I’ll manage. I’ll go to Palestine.’ At that time Israel was not Israel yet, it was Palestine, and there were a lot of German Jews. Austrian Jews, who had a little Seventh Avenue. They made dresses, baby, dresses, suits, anything you want. Just like Europe, only on a very small scale.”

Albert’s uncle gave him the go-ahead. “Imagine! I was 17 and I have no idea how you buy goods, how to buy sizes or anything. But there was a man from a competitor store who had fashion. This man was a good friend of mine. He was much older than I, about 55 or 60. So at night, instead of going out with all the girls- they had beautiful girls there, girls from Romania, from France-instead, I stayed with him. and we talked and he taught me how to buy and how to choose a size range, and the next morning I went, green as a cucumber, to buy dresses. That’s how I started. That was the war years, 1941-42.”

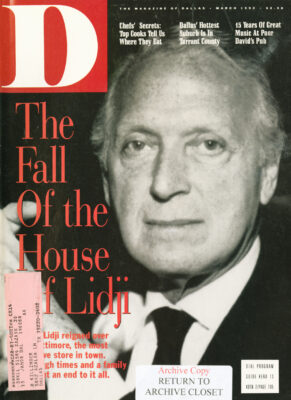

Albert Lidji is sitting behind his desk at Lou Lattimore. It is two weeks since his company filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. This morning he was unable to get into his own store. The locks have been changed and he was let in by Irv Rosen of Rosen Systems Inc., the firm that will liquidate the merchandise ana the fixtures left in the store. Albert, who is 70 years old, is impeccably dressed in a pinstriped suit, and his gray hair curls boyishly over his shirt collar.

“I had an architect, a beautiful architect, and I wanted him to design the department. And I said to him, look, what I want is this. I want a beautiful red carpet. And we had a factory in the store that made furniture so they could make anything for me that I wanted. I had an image-I’d been to France as a young boy. I knew. So I said, ’I want all the mirrors of the department to be pink.’” The Egyptian women, he says, “were pretty from age 12 to age 16, then they got big. But the girls didn’t know about the mirrors and the women said. ’Oh. that’s pretty.’ She looked at herself and she looked thinner, suntanned. You know pink mirrors make you look very good. So then in the middle of the night when we were doing things I said, ’How am I going to show the dresses?’ We didn’t have hanging racks then like we do today. So I said to him. make me two beautiful English tables. So I saw myself throwing the dress on the table.” Albert stands up and with a grand sweeping gesture, lays an imaginary gown on a gleaming wooden table.

“What a dreamer I was, throwing the dress on the table.” He makes the gesture again. “Like a big dreamer.” He shakes his head and sits back down, casting a glance at the suitcases lying on the floor for the personal belongings he has yet to take out of the store.

Albert’s fashion department was successful, and after a time he stopped buying from Palestine and instead designed clothing for his own seamstresses to make. After the war was over, when goods were once again available, he bought more ready-to-wear in England and France. His business continued to grow until 1948 when the state of Israel was born and Palestine was partitioned.

“Overnight I was a fifth column,” recalls Albert. “All my Arab friends, my Moslem friends, would no longer eat breakfast with me. Because I was Jewish. I was heartbroken.”

Albert soon married a chic Jewish woman of Spanish descent named Nicole. Because of rising anti-Jewish feelings in Egypt. Albert decided he had to move. Within two years he and Nicole settled in Dallas. A friend, the American consul in Cairo, had told Albert. “When you go to America, promise me you will never settle in New York because you are 27. 28, and in New York you will be just another foreigner. I want you to go inside America.”

“Where?” asked Albert.

“Texas.”

And so it was. Albert and Nicole were swayed by the friendliness of the people in the wind-swept city they visited. Recalls Albert: “The men took off their cowboy hats and all the girls in the restaurants said, ’Come back, please come back.’ My wife said to me. ’The people here are very polite.’ We thought maybe we left too much tip.”

After a stint at Neiman Marcus’ Younger Set Shop, where he learned what American women liked, and after losing $50,000 on an oil property. Albert decided to buy his own store. He found out that Lou Lattimore was for sale only a couple of years after its founding by a woman of the same name. “She went broke because she gave credit to anybody, to the maids of customers, to everybody who came around.” he says. Louise Lattimore had been backed in business by two men, Sam Klein and Sam Pearlman. At the time, says Albert, the store was doing about $125,000 a year in clothing sales and $50,000 in hats. There was a milliner in the store.

In 1952, Albert offered to buy out Klein, an oil man. “Very big,” says Albert. “He was very big in oil.” Klein’s asking price was $39,000, but Albert made an interesting proposition. He offered Klein his oil well share, as well as $5,000 in cash. “I’m giving him $50,000 of nothing I can use, maybe he can use it, deduct it from his taxes, see?”

At first Klein refused, then he accepted. The store’s sales volume began to grow, and Albert, with his uncle’s backing, later bought the building and. eventually, bought out Sam Pearlman.

Albert’s parents and his uncle joined the rest of the family in Dallas in the late ’50s. “I was working very hard. We had our second child, my wife was home with the children, I was working like a mad man. I was delivering, doing the windows, going to New York to buy, back and forth, everything. I was on fire. And I loved it.”

LOU LATTIMORE CATERED TO THE CAR-riage trade. As Alan Lidji, 42, Albert’s eldest son. puts it. “the upper end, the elite. Women who generally came by appointment and would spend the afternoon with a saleslady who would be her saleslady for years.”

Alan remembers that the women of Dallas in the 1950s looked quite different than they do today.

“It wasn’t uncommon to look into the racks and see size 18, size 20. That was the bulk of the business. They kept those sizes in the back. Women who were big didn’t like walking into a store where there were big dresses all around. They wanted a store where the clothes were petite and beautiful, where the salesladies knew to go get the dress for a larger woman. Then, there was no such thing as the young rich. There were no 20-or 30-year-olds in a position to buy these clothes.”

The store offered the rare commodity that some women will pay untold sums for: the fantasy of youth, of beauty, of desirability. The promise of transformation-that the right dress, shoe, scarf, handbag or lipstick will make her look like something else, something closer to her inner vision of herself. Says one longtime saleswoman. Polly Depuy, “We had a lot of fun in the store. We played lady all day long.”

And Albert Lidji. because of his own particular affection for women, was a master at creating that fantasy in a manner that felt absolutely right-not phony, not pecuniary.

In 1965. the store underwent a major remodeling, and Albert tried to attract the daughters of his customers of the previous decade by buying clothes from younger designers. He bought more and more in Europe, in part because Neiman Marcus had the exclusive right in Dallas to buy many American clothing lines.

But Albert got a lucky break in the late ’60s. Stanley and Lawrence Marcus had a fight with American designer Norman Norell. The fight was so bad that Norell decided to stop selling to Neiman Marcus.

“Norman Norell was the most important designer in America and in the world,” says Albert reverently. “The most beautiful clothes you’ve seen in your life. Maybe you wouldn’t understand. They were old ladies clothes, but at this time, who was buying clothes, they looked like old ladies. The little suit, the short jacket with the wide collars, the cuffs, the button.

“So I called Norell, and Norell said, ’Well I heard about you, Mr. Lidji. The time will come when we’ll consider.’ That’s all he said.”

Not too much later, a representative of Norell arrived in the store. He had come to town to visit Lou Lattimore and Marie Leavell, the two women’s specialty shops that defined the end points of the Miracle Mile on Lovers Lane. Not long after that. Albert travelled to Norell’s opening in New York to buy the line.

Albert recalls: “It was 9 o’clock at night. Beautiful showroom, 550 Seventh Avenue, cocktails, champagne, everyone in black tie. Next to me was sitting Mr. Revson of Revlon because he had the [Norell] perfume at the time. And on the other side was an old lady from Tennessee called Mrs. Leclide. And I saw the most beautiful clothes for spring, all heavy wools and tweeds. ’Oh,’ I said, ’we’ll never sell that in Dallas.’ So I asked Mrs. Leclide, I said ’Excuse me, what are the prices of these clothes.’ She said ’Son, they’re high.’”

“The show ended at 11 o’clock. My appointment was at 10 o’clock the next morning to buy the line. I was staying at The Savoy then. I could not sleep. I was so nervous, so scared, the confusion in my mind. How am I going to buy clothes like that? Anyhow I said to myself, finally. I said, ’Look, come on. you lost $50,000 in the oil, you lost money in stocks.’ Then I had a great courage at 1 or 2 in the morning. I showered and dressed and I went to Reuben’s to have breakfast. Then I went back to the hotel. Eight o’clock I was in the street. I felt like a million dollars.

“So I bought Norell, I bought like I was buying $100 dresses. I bought so much. I was supposed to buy $18,000. I bought $21,000. I didn’t even add. I put my order in and I went home.”

And the ladies bought. Dorothy Vaughn was the first one in after the merchandise arrived. Albert had just renovated the entry of the store-brick floor, glass doors, elegant showcases. “Dorothy Vaughn was the loveliest lady in the world.” he purrs. “She was a princess, a princess at heart. She said ’Albert, your store looks like I. Magnin.’ It was gorgeous, they’d never seen anything like it.” Dorothy Vaughn bought four pieces. “My heart was so glad.” recalls Albert, reaching out his arms. “Because Norell was the God.”

The ladies bought so much-of the $600 to $800 wool and tweed suits that had so worried him-that Albert had to reorder. Eventually, he says, “I became the number three store in Norell sales after I. Magnin and Bonwit Teller.

“I became the star of Norell,” says Albert. “The person who really put me on the map was Norman Norell. When Norman Norell sold to me, everybody in New York wanted to sell to me.”

THE ’60S AND 70S WERE THE ZENITH, the golden years for Lou Lattimore. Says a Dallas businesswoman: “When Yardley and Old Spice were the scents in Dallas, can you imagine walking into Lou Lattimore and finding ’Norell’ misting in the store? There were also the most fabulous clothes in the world that no one else could find. And the best sales help.”

Alan Lidji observes: “In the ’50s and ’60s, my parents were something of a novelty. They were seen as interesting. They brought to the city something that was never here before-French people in Dallas. If there was one lever they were able to use to make the store, it was that.”

The aura of European sophistication kept the store riding high through the “70s, even in the face of competition from shopping malls, department stores and other specialty shops. In the 1980s, annual sales reached between $9 million and $12 million, including the lease departments, like cosmetics and shoes. In the early ’80s a beauty shop was added.

Besides being a money maker, Lou Lattimore was a warm place, very much a family affair. In addition to Albert’s siblings, his son Craig started working as a buyer in 1981. Son Brian took care of the store’s legal affairs.

The salesladies, many of whom had been there for years, felt a kinship with the store and the Lidjis. “We loved working there,” said one. “You have no idea how happy we were, what a nice place it was.”

Albert’s brother Jacques, who was in the hotel business, came by for lunch every day. He and Albert were so close that, in addition to their lunch meetings, they spoke every night on the telephone, even when Jacques lived in Houston and New York. “There was such love in that family,” says a former employee. “I used to hope that my children would grow up to be as close as those brothers.”

But when the price of oil dropped precipitously in 1986, and then the stock market crashed in October 1987, the store received a shock from which it never recovered.

The economy had experienced other recessions, but Lou Lattimore, according to Albert, had never been badly hurt. “Before 1986, it was the white collar who were affected. Not the rich people. But in 1986, it was the rich people who got hurt.”

Albert always believed things would get better. Says a competitor: “The writing was on the wall in 1984-1985. The prices [of clothes] had gotten too high, it couldn’t last.” But, says another observer, “Albert always thought the roads were paved with gold.”

The recession itself didn’t kill Lou Lat-timore. But it put into focus two deadly forces whose origins hark back to the early 1980s: family divisions and management errors. In a decade, the store would be dead, the family splintered.

As a member of the family explains. “What killed Lou Lattimore was overspending, overbuying, the recession and the divorce.”

IN 1982, AFTER 32 YEARS OF MARRIAGE and three sons, Albert and Nicole were divorced. A few months later, to the surprise of many. Dallas society columns announced that Albert had married 26-year-old Martha Gaylord. She was the daughter of the elder Martha Gaylord and the adopted daughter of Dr. Robert Gaylord of Highland Park.

The news of 60-year-old Albert’s marriage to a woman who was but a child in the eyes of his middle-aged clients produced many aftershocks. The store lost some customers right away. Says a former saleslady: “Some of the clients were offended. Dallas is a conservative town.”

The divorce marked a turning point in the history of Lou Lattimore and the relations in the family. Its effects were far more profound than the loss of a few clients. Over the next 10 years, everything that had made the store strong, except Albert’s talent, disintegrated. The style of the merchandise changed. Albert’s credit and available cash were halved, reducing his ability to buy as he had before. The store gained one employee-Martha Lidji-but lost many others: its comptroller, Armand; its heir apparent. Craig; its manager, Henry; most of its major salesladies and those salesladies’ clients.

The year that Armand left, in 1986, gross sales were $9 million. By 1990, sales had plummeted to $4 million before bottoming out at $2.3 million in 1991. Bankruptcy filings show the store owed vendors $1.6 million when it closed.

Soon after the marriage, Martha began the difficult process of trying to win the affection of a family whose members were not only twice her age, but also had known Nicole, the first wife, since childhood. She also walked the dicey path of forming relationships with Albert’s three sons, who remained close to their mother.

Likewise, when Martha got more involved with Lou Lattimore in 1987, she had to negotiate a delicate balance between newcomer and owner’s wife. By all accounts, the employees of Lou Lattimore welcomed Martha’s arrival. But as Martha’s relations with the Lidji family deteriorated, so did her relations with the store’s top saleswomen. By 1991, most were gone, some bearing bitter stories about Martha.

Some employees accuse Martha of lavishly using Lou Lattimore to supply her own growing wardrobe and thereby contributing to the store’s death. In turn, Martha and Albert say some salesladies were guilty of improprieties. Differences between the proMartha and the con-Martha camps are so great that their versions of events are large-ly irreconcilable-even when it comes to the recitation of facts. Ten former employees were interviewed for this article; most agreed to speak only if their names were not used, for fear their jobs would be jeopardized.

MARTHA WAS 4 YEARS OLD WHEN HER natural father, Robert Wayne Bumpas died. Left with three children and no in-surance, her mother returned to work, doing what she knew-acting. She flew often to New York to shoot commercials. Young Martha lived with her grandmother Dallas. Her grandfather worked in Arkan-sas, so she enjoyed no steady male presence between the ages of 4 and 7. “I’m sure that has something to do with the fact I married Albert,” she says. “I think there was something of the father figure in it.”

She graduated from Hockaday in 1973, then says she attended a semester at Finch College in New York before being accepted into a master’s program at the Yale School of Drama to study acting. The school admits a few students every year who do not have undergraduate degrees.

Martha says she completed the three-year program at Yale and collected her certificate of completion, although records at the Yale alumni office indicate that Martha Gaylord withdrew after two years and did not receive a certificate.

Martha then moved to New York to act and got a bit part in a Ryan O’Neal movie called So Fine (in which she played a fashion buyer from Houston). She also won kudos for her first major theater role, getting a 1978 nomination for a Drama Desk award for best actress in a play called The Elusive Angel.

She and Albert met in New York, says Martha, at a backer’s party for a play she was to appear in. They dated for a few years although Albert remained married. “We fell in love, and I’ve been with him ever since, ” she says. “Now my life is his.”

Before Albert’s divorce, Henry often spoke with Martha on the telephone. ’’She was getting very friendly with me,”he recalls. Albert, after speaking with Martha for a while, would simply hand Henry the telephone. “And I had to finish the conversation with her,” he says. “She never really called me, except the one time when [Albert] told her he wasn’t going to get a divorce. He was going to stay with his wife. Then she called me and she started putting on this air of tragedy. ’If you don’t hear from me tomorrow, you know.” And I said, ’No, come on, you’re young yet,’ and all that stuff. Finally, I almost said. ’Well, do whatever you want to do.’ I don’t think she would have commit-ted suicide, anyway.”

Albert’s brother-in-law Armand warned Albert that if he divorced, he would lose half his cash and credit because Nicole was en-titled to 50 percent of the estate. This delayed Albert’s departure for a time. When Albert finally married Martha in 1982, he was looking forward to passing on some of the responsibility for the store to his son Craig, a recent Princeton graduate who had joined Lou Lattimore in 1981 as heir apparent and buyer. Albert was overjoyed that one of his sons was interested in the business.

Craig, like his father, is artistic loves fashion and has an eye for the new. He also shares his father’s love for doing things right-which meant lavish trunk shows, beautiful window displays, first-rate lighting. Craig did things “top drawer, first class,” with little eye to cost.

Albert knew that the store had to attract a younger clientele-the ladies who were his clients in the ’50s and ’60s were getting on in years. Craig’s taste was young, forward, avant-garde. However, some of the clothes he chose, though beautiful, were a bit too hip for Dallas. A good deal of merchandise wound up on the sales racks.

Still a novice, Craig was working without a lot of supervision from Albert. Says one employee who worked with him: Craig was buying more than he should have; he bought some things that were outrageous, but also he bought some great things. Albert gave him too much leeway. If he had told Craig to stay on a certain budget, things would have gone differently. But when Mr. Mires left, there was nobody left to say, ’Stop here.’”

In 1986 Armand Mires left his job as comptroller after a disagreement with Albert over a family-owned property. -“Armand was tight, people weren’t too fond of him, but he kept the money under control,” says a former employee.

At the same time, as Armand had predicted, Albert’s post-divorce money crunch left the store in a weakened position. There was less cash available and a smaller cushion to absorb losses. Then, in 1986, the price of oil collapsed, and the next year the stock market crashed. Says Albert: “The state was in total fear and panic. People with big money were going Chapter 7. Chapter 11, Chapter 7. Chapter 11. The most important people in Dallas.”

The last big clothing purchase made by Albert and Craig was in 1987. After the stock market crash, huge amounts of merchandise were left unsold in the store, and it all went on sale.

In a suit to recover funds from the store’s bill collector, Albert stated that from mid to late 1987, Lou Lattimore was in a “desperate financial condition.” The store began legal proceedings against customers for unpaid bills. At the time, the store had “several hundred thousand dollars” of outstanding accounts, according to court documents.

Albert asked his family for help. Nicole, as part of the 1982 divorce agreement, had agreed to leave some of her stocks at the bank as collateral for an existing loan. In 1987, those stocks were valued at about $240,000. In response to Albert’s request, Martha and Jacques put up additional collateral to secure a bigger line of credit. Jacques gave over $200,000. Martha put in about $50,000 in collateral. Jacques’ agreement stipulated his collateral would be released first as the loan was paid down. Martha’s deal gave her 25 percent of the store.

Though Martha’s contribution was less than Jacques’ or Nicole’s, and though Albert gave her a substantial interest in the store, Albert now villifies his relatives-except for his recently deceased sister Laura-for being greedy and praises Martha for trying to save him with her generosity.

Indeed, as Martha and Albert tell it, Martha gave $100,000, as did Jacques and Nicole. They also imply that Jacques was responsible for the bank eventually calling the loan-claims strenuously contradicted by family members who saw the documents drawn up. Both Martha and Nicole lost their collateral when the loan was called.

At about the same time, Craig was facing his own difficulties. Martha “came in and undermined a lot of things [Craig tried to do],” says a former saleslady. In the summer of 1987, Craig left on bad terms with his father.

In an attempt to cut costs, Albert did not replace Armand with an experienced comptroller. Instead Albert moved his youngest brother, Henry, from the sales floor up to the office and put him in charge of a new computer system. For a while, Henry would also continue some of his sales-floor duties.

At about the same time, Albert decided he wanted the beauty salon to pay more rent for its space adjacent to the store. The proprietors, Michael Ventriglia and Stephen Dunn, did not agree and left. One saleswoman says she had 20 to 30 clients who came in the store to shop every week before or after their hair appointments. “You can’t replace that kind of busines, but Mr. Albert wouldn’t listen. He said, “we don’t need it. Customers will always come over here.’ “

But they didn’t come as often and the salon remained empty for six months. “That was the first big mistake,” says a saleslady. “The second was that Martha took all the clothes for herself.”

Martha slowly assumed more control. Soon, she banished Henry from the sales floor. “She said the customers didn’t like him.” according to a saleslady. “She did all these things to make him uncomfortable. She did all these things behind Albert’s back.” The saleswomen noticed that although Martha tried vigorously, tirelessly, to win friends in the store, she could just as quickly turn and devastate an employee with a few choice words. Martha, according to former employees, took advantage of their affection for Albert. “She used to threaten everyone that Mr. Albert would commit suicide, to get them to do things,” says a former employee who adds, “I think it is she who thinks about suicide, not Mr. Albert.”

Some sales people tried to approach Albert about the changes Martha was making, but, according to one, “You couldn’t tell Mr. Albert certain things.”

Albert continued to do the large part of the buying, and he worked the sales floor. But sometimes he left early. “Martha would say ’Go home Albert, go take a nap,’” recalls one. And he did.

IT IS A FEW WEEKS AFTER THE CLOSE OF the store. Martha is very thin and dressed like a model. “Listen, that’s what this business did to me. When I married Albert I was probably 20 pounds heavier. It is hard when you’re being scrutinized every day.” When she speaks-often in a stuttering, tentative fashion-she inspires listeners to want to hug her and tell her everything will be all right.

Martha says she has heard awful rumors about what people are saying. “Whenever you have family involved. . .”

Then, she asks, “You know, all I wonder is, all the people who say I married him for his money, I wonder what they are saying now. What are they saying now?”

During an interview in the Lidjis’ University Park condo, when Albert has left the room, Martha confides that she’s worried about her husband’s spirits. She reaches into a desk and pulls out a copy of Final Exit, a how-to suicide book by Derek Humphrey, founder of the Hemlock Society. “He doesn’t know I know this is here,” she whispers, holding up the book.

Other family members and those who know Albert doubt he contemplates suicide. “Albert loves himself too much,” says one.

AFTER BEING BANISHED FROM THE sales floor, Henry spent most of his time on the computer, taking care of inventory. He also worked the telephones, trying to keep vendors unruffled, though many were not getting paid. Says Henry: “I was able to get merchandise from them. I promised them a little check now. I always made some deals with them. Now Albert does not know how to do that. When I left and somebody called on the phone, people told me he said to them, ’So sue me!’ Like that.”

Throughout 1988 and 1989, Albert and Martha tried to get the store back on course. As 1989 neared an end, it seemed as if they had. Henry, tallying up the yearly figures, believed there was good news. Not only would the store pay off its accumulated losses, but it would also show a small profit. Then, the accountant pointed out a tremendous, unanticipated shortage-$350,000 for the year.

Albert went ballistic. He insisted it was a false shortage resulting from Henry’s misuse of the computer. “Henry was lazy! He was doing nothing!” cries Albert today.

“The banks would not support us anymore,” says Albert, “because when you see on a statement that you lost $400,000 because of shortage, the banks say, ’Excuse me, my friend, we can’t do business with you.’”

Albert told Henry he would have to take a cut in pay and be replaced on the computer by one of the new saleswomen. Henry was insulted and left. Today, as Albert tells the tale, Henry is responsible for everything that went wrong with the store. “I’m broke today. I lost $5 million because of Henry!” he says.

“There was nothing wrong with the computer,” says Henry, who called in the store’s accountant, David Moore, to try to reconcile the discrepancies. “The accountant told me the shortage was real, he even checked SKU numbers on the computer at random and found that I had done it right.” (SKU numbers on sales tickets identify garments.)

However, David Moore says that in checking several hundred SKUs, he found that some had been entered properly and some not. He could not determine the reason for all of the discrepancies, but says the shortage was not the sole reason for the store’s loss of funding. The banks, he observes, “were uncomfortable with the company’s ability to make a profit.”

Another family member says, “Albert never believed there were shortages. He always blamed them on the computer or on somebody else.”

Says Henry: “I was very hurt. I’m surprised that a brother of mine wouldn’t listen to me after 25 years. I even left Dallas for a while. I just wanted to get away from people saying what happened, what happened.”

Today Henry, who now sells handbags at a department store, theorizes that the shortage that got him fired was due in part to a reduced staff and less vigilance at the front door, resulting in more thefts.

After Henry left, Martha was the most senior employee, aside from Albert, though by her own admission, she knew little about retailing, clothes or business.

Martha made a costly mistake when she got involved in the store, say former saleswomen. She tried to tell them how to do the jobs they had been doing for decades. Women who sold a million dollars of merchandise a year and who made $60,000, $70,000, $100,000 themselves. Tough, hardworking women who were the best producers in town.

What she did, they say, was try to control the clothing they could sell. She prevented any new merchandise from going to the sales floor before she looked at it. She tried on all the clothes-she says this was to see how the clothing would fit her clients; employees say it was so she could choose the pieces she wanted for herself-then gave pieces to certain saleswomen. The best pieces went to those who were on her good side.

This drove the saleswomen wild. “It meant that to get the clothes, you had to be nice to her, and if she was mad at you, she wouldn’t give you the clothes to sell. This is our livelihood,” says one.

For her part, Martha says that her problem was being too friendly with the help. “When you’re too nice,” says Martha, “and then you say no, they hate you.”

Martha and Albert say that the saleswomen cheated them. They lay out the schemes some of them used to hold on to sales: charging clothes to a customer pending her approval, then charging the garment, if it was rejected, to another customer-and sometimes, in the end, having to relegate the garment to the sales rack if it got too late in the season.

Martha was perceived as pushy and abrasive by some clients. She tried to encourage sales by peeking into the fitting rooms and bringing extra clothes to women who were already being helped by their salesladies. Saleswomen report that some of their clients left as a result.

Some customers did like her. Jeffrey Weiss, whose wife, Sally, is a friend of Martha, says Martha was “a tremendous asset to the store. She was a good salesperson and she’d run around 60 miles an hour showing things.”

Eventually, the saleswomen revolted. Between 1987 and 1990, every major saleslady but one left the store. And they left with their clients. They went to Neiman Marcus, The Gazebo, Loretta Blum.

This loss was a knife wound to the store’s jugular. Many of the saleswomen had been there for 10, 15, 20 years. One woman worked there six days a week for 26 1/2 years. “They were heartbroken,” says a family member.

ASIDE FROM OBJECTING TO MARTHA’S control of the merchandise, some of the salesladies wondered why Martha took so many clothes out of each order for herself. “What they don’t realize,” says Martha, “is that the clothes that came in for me were ordered for me.”

Martha says that dressing well was essential for her job and that customers often bought the clothes they saw her in. “What do you think Loretta Blum wears!” she says. “What does Shelle Bagot [of The Gazebo] wear?”

Martha dressed almost completely in Thierry Mugler. She is said to have taken one or two pieces, whose wholesale cost was around $1,000 per piece, from every box of arriving merchandise. “With her it was always top of the line, always the most expensive shoes, the most expensive bags, the most expensives suits and dresses,” says one insider.

Martha had two offices in the store. One was full of clothes and was kept locked. Says a former longtime employee, “It was very strange that she had all these clothes locked up in a little room. She never let anyone in there and when she went in she locked it behind her. You were not allowed 10 paces from that door. Then someone caught a glimpse of what was in there, and, in addition to all the clothes, saw a pile of handbags that we all thought had been sold months before.”

When asked about the room, Martha says: “It was my store!”

Later, Martha says that the clothes in her room were being held for customers. Employees say that only occasionally did they see clothing come out of Martha’s storeroom and go to clients.

“That is an outrage,” says Martha in answer to suggestions that she may have taken too much merchandise from the store. “That is a blatant lie.”

“Someone from the family said that!” she cries. She is told that no, it isn’t family.

“Abusing, abusing, they were takers, you understand?” says Albert about his family, following her lead. “Everybody was a taker. They are just the ugliest people in the world.

“The day I stopped they hated me,” he says. “Do you understand? And they thought when it stopped, it was because of Martha. That’s the psychology. And don’t look any further than that.”

“It took her two years to destroy something he worked 40 years for,” says a sibling. “Albert is a real nice guy. And there’s no fool like an old fool.”

But Martha still has loyal supporters among the ex-employees. Claire England, who ran the computer for the last two years that the store was in business, says, unbidden, “They just love each other so much. He’s bankrupt. Anybody else would maybe go. If she married him for his money, she wouldn’t stay.”

In the final two years, Albert sank an additional $2 million into the store, in part by selling the lot next door. Martha sold off some of her jewelry in the last few months, she says, to make payroll.

“We have had a whole family torn apart,” says an employee who left over a year ago. “Jacques lies on his sofa with tears in his eyes almost every day. These people went to lunch with each other every other day, sometimes every day. They were the closest brothers, the closest family. And now they’re not even speaking. And when poor old Henry found out about [the Chapter 7 filing] the other day, he about couldn’t handle it. Now doesn’t that just make you hurt inside?”

Albert feels the loss of the store deeply. “I was heartbroken. It’s a very great part of my life. When you grow in a store like that, the store becomes your child, it becomes your family, it becomes everything.

“We had the most beautiful clients in the word… the loveliest ladies I ever met in my life. We had an affair with our clients. An affair. A love affair.

“You know, when you have your armsopen, everybody comes to you.”

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte