Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

Dave Fox cradles a cup of hot coffee on a cold morning and grieves over the loss of a son. “I don’t like what he’s doing now at all,” the former county judge and founder of Fox & Jacobs says with a slow shake of his head. “It’s totally uncalled for, dangerous, bad, insulting. And I’ve told him so, several times. He’s one of the kids that we’ve got that we don’t like what he’s doing at all.”

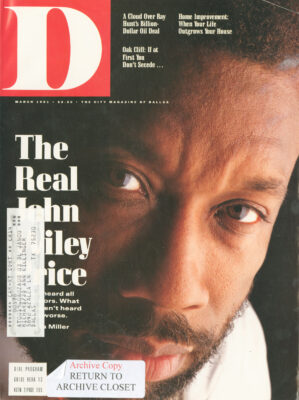

The “kid” who so worries Dave Fox is Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price. What Price has done, as everybody knows, is turn Dallas inside out. And Fox doesn’t know what to do about it. He’s tried everything he can think of—kept in touch by phone; had him over to the house; offered his advice, support, and understanding. Even suggested professional counseling.

But, like a true rebellious son, Price will have none of it. In fact, he has made it clear, Fox says, that he is willing to sacrifice Fox’s friendship—all friendships, for that matter, and all the strides he has made in business or politics—to do whatever it takes to wake people up to racial injustice in Dallas.

Fox puts his coffee mug down on the polished conference table, links his arms behind his head, and gazes out a wall of glass at an awesome view of downtown—a fitting backdrop for someone who literally helped build this city. He had big plans for Price, he says. Big, big plans.

Fox wanted Price to become the first minority mayor of Dallas. He wanted him to be successful in business. He wanted him to be a leader. A coalition builder. A man who could pull this city together. And he could have. Fox would have seen to that, if only Price had let him.

“I didn’t want him to go up to Washington,” Fox says about Price’s much-publicized plans to run for Congress in 1992. “I told him he should stay in Dallas. He could do a lot more in Dallas. I would have helped him in any way I could, and he knew that.”

But that was before the billboards and the Bernal incident and the broken windshield wipers. That was before the pickets and the boycotts and the call to take up M-16s against the cops. Now, after all those burned bridges, would Fox still help Price? “Maybe not now,” Fox says.

There are times when Dave Fox, like so many Dallasites both black and white, wonders if he even knows the real John Wiley Price. Perhaps no public official in Dallas history has carried the burden of so many people’s hopes. It’s not just Fox who believed in Price and his potential for leadership. And yet, few public figures in Dallas history have been surrounded by more unsavory rumors than Price. In the black community the stories are legion: the violence. The shady deals. The expensive toys. The women.

While Price does have enemies—white and black—who would not hesitate to smear his name, a careful examination of his record reveals evidence of behavior that runs the gamut from mere bad judgment to outright unethical and even illegal acts, including blatant conflicts of interest, influence peddling, kickback demands, sexual harassment of subordinates, even sexual assault. When the facts are sifted from the rumors, the picture that emerges is that of a gifted, charismatic leader whose desire for wealth and personal power led him to squander his potential and betray those who trusted him.

• • •

The John Wiley Price that Dave Fox thought he knew was a polished, intelligent, forceful county commissioner who worked tirelessly to do what was best for the county. He had good ideas, he made good points, he put in long hours. “I found him to be a very interesting fellow,” says Fox, who became county judge in 1985 after Frank Crowley died. “Very dedicated. Very intense. I got to liking him right away.”

The John Wiley Price that his constituents thought they knew was passionate and personable and caring. He listed his home number in the phone book. He returned their calls personally if not always promptly. He was there for them in times of crisis. He was truly, as he has become known south of the Trinity, “Our Man Downtown.”

The John Wiley Price that the rest of Dallas thought they knew was the one who screamed at them from their TV sets and prepared to declare war on Dallas at a moment’s notice. He could find the racial angle in any dispute. He was a showboat, a rabble-rouser, a poser. Some were certain he was even worse than that. How, people often asked, can that guy drive an $80,000 sports car on a commissioner’s salary?

The answer to that question can be found in that part of Price that isn’t so easily known. If John Wiley Price is anything, say the handful who know him—including his ex-wife and his ex-girlfriend, former and current staff members, business associates, and friends—he is a hustler. Sometimes he wants power, sometimes money, sometimes sex. He’s always out to cut a deal, on his terms, for his gain. And if you don’t recognize that in him, then you won’t ever know him.

Ironically, these people say, it was Dallas that taught him how to hustle.

Price came to Dallas from Forney in the summer of 1968, just a green kid out of high school, hoping and praying to get a job as a janitor at Sanger-Harris. The day he applied for that job, the store manager at Big Town sized him up and made him a menswear salesman. Seven months later, he was hawking the store’s big-ticket items, TVs and stereos, for a 5 percent commission plus manufacturers’ bonuses. He was so aggressive, so competitive, so intense, he recalls, that company brass were forever admonishing him for stepping on other employees’ toes. “You had little guys who had been there forever, and hell, I was starting to hustle hard and take money, so they were complaining,” he says. “I’d be popping the stereos, and people would come in and look at them, and I’d help ’em. I was aggressive, yeah.”

And he stayed that way, no matter how much trouble he got in. “It was more money than I’d ever seen.”

Back in those days, Price’s main cause was making money, pure and simple. Sure, he knew what racism was—it was hard not to when you had to buy your hamburgers at the back door of the all-white cafe in Forney, when you and every other black kid in town were pulled out of school to harvest cotton in the fall, when your English teacher insisted on calling you a “nigra” in class.

But even though he spent many an afternoon in the principal’s office for having it out with teachers, Price did not become politically aware until 1970, when he enrolled at El Centro Community College downtown to study computer programming while he worked at Sanger’s. Back then, the black student movement was strong. The Black Panthers were active on campus, and people like Marvin Crenshaw, a fellow student, were learning how to make waves. Price, running on a black consciousness platform, ran for a spot on the student council and won.

It was during this time that Price met Vivian Pauline Salinas, who was part Italian and part Hispanic and had two small children. “I met him at a club—the Red Jacket on Maple, across from the Stoneleigh Hotel. It’s not there anymore,” she says today. “He used to go there with his college friends. At first I had a boyfriend, but I kept dating John, and I fell in love with him. Oh, he was really good to me and my kids. He bought them stuff. He bought me things.”

Nine months after they met, Price’s father, a part-time minister, married them in a little church in Forney. It was Valentine’s Day 1970. He was 19. She was 23.

Price does not talk much about having married a woman who is not African-American, but he doesn’t duck the question. He married Vivian, he says, because he was young and new to the big city, and “she was the first lady who looked at me.” He says the relationship would never work today.

“I doubt very seriously I could fall in love with an Anglo woman now, or anyone who is not an African-American woman,” he says. He would need someone, he says “who understands me, understands the culture … understands my pressure and what I’m going through.”

The Prices had a son nine months after they were married. It was Price’s first child, and, his ex-wife says, his last. “He just wanted to go out and have a good time and not worry about getting somebody pregnant,” Vivian says with no bitterness. “So he got a vasectomy.”

Some of the media’s reluctance to investigate Price stems from simple fear of being labeled racist, but Price also works diligently to charm the press.

It was Price’s penchant for having a good time, Vivian says, that led to the couple’s separation three years later. “I guess he married [too] young,” she says. “He started being a playboy.” But Price refused to divorce her, she says, and they stayed legally married for the next eight years. The relationship was not always friendly, and things got progressively worse over the issue of child support. At the time of the divorce, which was final in April 1981, Price was ordered to pay $35 a week in child support, a sum Vivian felt was inadequate—especially in light of the fact that he didn’t always pay it. “I went to see I don’t know how many lawyers. No one would take the case. Once they heard the name, they wouldn’t take it,” she says. “I had to end up going through [then attorney general] Jim Mattox, but it took them nine months to do anything.” Price says he gave Vivian money not necessarily regularly, but whenever she asked for it. Often, he says, he gave more than the $35 ordered.

For 20 years, Vivian Price has seen her ex-husband get more prosperous and much better known—going from Sanger-Harris to an office job in the Dallas County Public Works Department to a newsroom stint with ABC Channel 8 to a paralegal job with Cleo Steele’s old law firm to the clerkship in Steele’s JP court to county commissioner. But no matter how well he has done or how far he has gone, John Wiley Price will tell you that he has never felt he owed his son child support.

Child support should be earned, not awarded, Price says. “I mean, your child support is something that you come and you work for,” he explains. So, as Price’s son grew up, he never spent a weekend with his father doing “kid things,” as Price calls them, “like the water waves.” Instead, John Jr. earned his child support doing things like helping his father fix up his Oak Cliff house and four rent houses he owned. “We did everything from roof houses to paint, sheet rock, to mow yards,” Price says. “You name it, and he did it.”

At one point, Price actually forged a deal with his son: he would agree to pay the boy his $35 a week, but he would have to mow his father’s yard for it.

“I always made the correlation between working hard and some remuneration,” Price says. “And what would happen is I would say, ‘Do this and you get support,’ and I could always tell when he wanted something extra because he’d say, ‘Come on, Dad, let’s go, we’ve got to do this, we’ve got to do that,’ so that always meant he wanted a little extra. And if he worked hard, and he did a little extra, he always got a bonus. He may have gotten $10 or $15. See, so I was trying to give him that correlation between working and responsibility.”

Vivian always felt Price should have paid the child support, regardless of whether his son mowed his lawn. Though the battle between them raged for a number of years, and the attorney general’s office garnished $2,659 out of Price’s county paychecks in 1987 and 1988, the matter never hit the press. That still amazes a former member of Price’s staff. “We just knew a reporter would find out. We just knew. There are investigative journalists who are allowed blocks of time to dig things up, and we just knew we were living in that type of city. But we weren’t. And now, of course, everyone knows that—because nobody’s ever really looked at John.”

Some of the media’s reluctance to investigate Price stems from simple fear of being labeled racist, but Price also works diligently to charm the press, going so far as to flirt with reporters and send them bouquets of flowers. “He plays them like a piano,” says the former staffer, who once arranged an interview for Price that resulted in a story the commissioner liked so much that he autographed a copy of it for her. “He’s a master at that. I’ve seen no one do it better.”

Perhaps the ultimate example of Price’s press buttering is the relationship he cultivated with Lawrence Young, an African-American reporter at the Dallas Morning News who covered the county during the time that the attorney general’s office was pursuing the commissioner for failing to pay child support. Young became so close to Price and his staff that, at one point, he began seeing one of Price’s secretaries, Cora Lewis. Lewis says she abruptly ended the affair several months later when she learned, to her great surprise, that Young was married. According to Lewis, after she broke it off, Young went to Price to complain. After that, she says, Price brought her into his office and savagely reprimanded her; essentially, she says, he told her that her obstinance was threatening his good relationship with the press. Lewis held her ground. Two weeks later, she was fired. Price acknowledges talking to the woman about Young, but says he did so only after hearing that she had obtained Young’s address and gone to his house. Price confirms that the woman was fired, but insists that it was for poor job performance. Lawrence Young maintains that he never discussed his private life with Price and refuses to comment further.

The story has become legend around the courthouse. “Lawrence was just notorious for being the press secretary for John’s office,” says one of the other county commissioners. “There never was such a sweetheart deal.”

Vivian Price knows that her ex-husband has enjoyed a honeymoon with the press. Back when she was contacting attorneys to help her with child support, she made a few phone calls to reporters, too. Nobody would touch the story.

Looking back on those days, Vivian now concedes that there was a moment, when John Jr. was 16, when the boy’s father seemed genuinely determined to put both time and money into his son. Price called her one day, she says, and told her that he wanted John Jr. to come and live with him. He wanted to get his son a tutor to improve his grades in school. “He wanted him to follow in his footsteps,” Mrs. Price says. But too much had transpired by then between father and son—John Jr. had been worked too hard, cursed at too much, left alone too often, his mother says. He refused to go, and she didn’t make him. Price didn’t speak to them for the next two years. “He loved John, but he really couldn’t show the love,” Vivian says of her ex-husband.

Today, Price says he does not recall ever asking his son to come to live with him. “I could have,” he shrugs. “I don’t remember.” For his part, John Jr. never talks about his father—not to his mother, not to his girlfriend, not to anybody. When the newspapers are filled with stories about his father’s latest broadsides, or when the nightly news flashes his father’s face on the screen, John Jr. says nothing. “He never says anything about him being his dad,” Vivian says. “It’s like he doesn’t even care.”

Father and son talk only occasionally and see each other even less. John Jr. and his high school girlfriend had a baby girl more than a year and a half ago.

Price speaks often and long about the vulnerability of today’s minority youth. He points proudly to the fact that a close female friend of his is a foster parent to a toddler named Matthew. “I love kids,” Price says, showing off a picture of Matthew that sits on his office credenza. There is no picture of his son or grandchild. “I take him to church on Sundays,” Price says of Matthew. “I spend every chance I get with him—a lot of time with him.”

Meanwhile, his own son, whom he says he hasn’t talked to “for quite a while,” struggles to make something of himself. He is 20 years old now. He works at a Winn-Dixie supermarket, cutting meat. His father shrugs. There is a hint of regret in it. “He’s doing his thing. At some Minyard’s, I think.”

• • •

Some things leave such an impression that we remember them forever.

For Price, it was selling C-6945 model Magnavox televisions—he still remembers the numbers—for a $25 bonus, plus $30 commission. He learned that when you give a little, you get a little. There’s always room to negotiate, always room to play. He’s been building on that concept ever since.

Price rarely buys anything today—from a Lotus sports car to a linen shirt—without shrewd negotiation. A bit of financial foreplay. That’s how, he says, he can afford to own the best. “What people don’t realize is that my clothes have always been about deals,” says Price of his notoriously flashy wardrobe. “I mean, I can’t walk in and pay $1,400 for a Gio Ferre. You know, I just don’t do that.”

What Price does, he says, is go to a store, like Oxford Street in Addison or Edwardian near the Adolphus Hotel, that will give him deep discounts because, he says, they want people to see him in their clothes. Edwardian, Price says, practically begged him to come in. “They always call me, saying ‘I want you to wear my clothes.’” But Price had a price. “He’s going to give me a deal, but he’s not going to give me a good enough deal,” Price says. “He said 20 percent—I said, ‘No, no, no, no, no. I said 40 percent’—he said, ‘No, no, no, no, no.’ But we go in and barter like that.” Managers at both clothing stores adamantly deny that they have ever offered any special discounts to Price.

Price says he has similar deals with Al’s Florist, a flower shop near Parkland. His campaign records show that he has spent $6,540 in campaign money there in the last four years. Price also seeks bargains at car dealerships. He hunts repos—for himself and friends—from banks all over town. He sells jewelry out of his briefcase. He buys junky antiques at flea markets and bric-a-brac shops and refinishes them. He’ll haggle shamelessly on just about anything.

“If they want too much money for it, he will stand there three hours and Jew ’em down,” says Betty Culbreath, his administrative assistant. “Once he gets them Jewed down, he’s not going to pay cash for it, he’s gonna give them $50 on it for them to hold it, then he’s going to pay it out. And then he gets it out, and then he takes it over to this other little man … who does a beautiful job of refinishing it, and when it comes out, it looks like it’s new. What you would think would be valued as a $4,000 bedroom suite actually cost him $400 at the most. That’s how he does it.”

Culbreath says her boss once spent five hours with her at a dealership, negotiating the price of a new car for her. “He stays that long because when he gets through talking and walking and looking and comparing and wearing your ass down, you are so glad to be rid of him, you will give him the discount … I bought a car, and I didn’t have to open my purse. And I’ve got a car payment, and it’s cheaper than I ever had in my life.”

Price’s ’89 Lotus was, he says, a dealer-driven floor model with 4,000 miles on it. He purchased it, title records show, for $60,000 at a time when the new ’90 models were going for $81,000 and saved an additional $3,600 in sales tax (he paid only $5) by showing the purchase as an even trade for his ’85 Ferrari, another $60,000 car that he got for considerably less in 1987, he says, because it was about to be repossessed.

Still, can Price really afford even a $60,000 car? Betty Culbreath bristles at the question—after all, if an Anglo politician were driving a Lotus, would anyone think twice? “Everybody seems to think that he has this whole wad of money that he goes out and pays cash with,” she says. “He doesn’t go out and pay cash; he does just what the rest of us do—he makes bank loans, just like everybody else. He’s a normal human being. He robs Peter to pay Paul, just like I do … Anybody who makes $72,000 a year [Price’s salary is now $75,000 a year]—I don’t make half of that, but I got a $140,000 house, and I got a new car.”

Price also has a house valued at $140,000 (which he says he bought in 1978 for $16,000, condemned) and a new car. But he has a lot of other things besides that. According to deed records, he owes $1,577 a month on a $137,752 loan he obtained several years ago from a bank formerly owned by Danny Faulkner (“Uncle Danny,” as Price fondly calls him). The money, borrowed from what was then the First National Bank of Garland, was used to buy a six-acre farm in Heath, Texas. He also has a loan for a six-carat diamond engagement ring he bought six years ago for his former fiancée, Austin anchorwoman Tonia Cooke. A third loan in Price’s portfolio, also obtained from Faulkner’s bank, is a home improvement loan for $52,160 that Price says was used to build a guest house behind his East Fifth Street house in Oak Cliff. And though Price will tell you that he can pay off all those loans and more by stretching his commissioner’s salary, evidence points to the contrary.

Price’s consulting specialty is minority protest—not how to start it, but how to snuff it out.

A review of campaign records indicates that Price paid off most of his personal home improvement loan with campaign contributions—a violation of state law, which prohibits elected officials from converting campaign funds to personal use. The records show that in 1989 and 1990 he used campaign funds to make two payments to the Garland bank, one for $18,700 and the other for $16,006. A cross check of deed records shows that Price’s home loan was due at the same time the payments were made to the bank.

When asked about the two payments, Price said, “I must have had a [campaign] loan there.” But there is no record of any such loan in his campaign report. If a campaign loan did exist, it should have been disclosed in Price’s campaign reports as required by state law. No such loan was ever reported.

Price’s income is not limited to his government salary and his campaign contributions. In fact, as others describe it, he uses his commissioner’s post almost as a springboard for his other ventures—ventures that often come his way through the contacts he makes as county commissioner. According to a former girlfriend, it’s all part of Price’s career plan. “John always said that he was going to stay county commissioner until he could run for Congress because he was going to use it to get into business the way white politicians do. That way, when he left office, he’d be all set up,” she explains.

One of Price’s sidelines, developed since he became a commissioner, is consulting. He says his partner, Kathy Nealy, runs the business out of her North Dallas home. Surprisingly, Price’s consulting specialty is minority protest—not how to start it, but how to snuff it out.

Their largest client to date, Price says, has been Darling Delaware, a Dallas-based company that owns some 35 rendering factories around the country that melt fat from animal carcasses for use in household products like soap. Price says he met the former president of Darling Delaware at a political function several years ago and has worked as a trouble-shooter for the company when problems—such as neighborhood complaints and protests—arise in some low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhoods where the rendering factories are located. In the past few years, he and Nealy have advised the company on ways of handling community problems in Fresno and Los Angeles, California, as well as Atlanta, Georgia.

In one case, Price and Nealy helped Darling Delaware when an African-American neighborhood group in Fresno sued its plant, demanding it be shut down because of the intolerable stench. Price also helped arrange for the law firm of Willie Brown, the African-American speaker of the California House of Representatives, to represent Darling Delaware when the company was threatened with a $250,000 fine for an air quality violation.

If Price has any moral dilemmas about hiring himself and Nealy out to do battle against the same low-income minority groups he fights for here in Dallas, he doesn’t show it. To the contrary, he says he’s doing those neighborhoods a favor. “You must know when I come in, it’s me and my deal,” he says of his arrangement with Darling Delaware. “It’s ‘I want to see you help. Have you been a good corporate citizen? If not, you have to do some other things. You either get me or get a lawyer.’”

Another more lucrative business that Price has is his gas station. Price and another business partner, Larry Smith, lease an Exxon Car Care Center, called Larry’s Exxon, located just off Interstate 35 in Oak Cliff. They pump about 100,000 gallons of gas a month, Price says, and bring in an additional $10,000 a month in repair work.

Price got the gas station only because of his rather unlikely friendship with Dave Fox, the Anglo Republican business leader who loaned him the money for the business. Price asked Fox for $50,000 to cover operating costs after, he says, NCNB turned him down for that amount. “I can own a Ferrari when I can’t own a service station loan.” Price says bitterly. “You loan me $80,000 to buy a damn car, but you won’t loan me $50,000 to go into a damn service station … They said, ‘Well, we don’t think it’s a good loan.’”

Fox not only loaned Price the money, but also required no collateral, just a signature. And though he won’t discuss specifics, Fox says the loan is being repaid, with interest, though the payments aren’t always on time. “It was a business deal,” Fox says, “and we are getting a good rate of interest, and I expect to get our money back.”

Price personally hustles a lot of business for the station, paying house calls on area firms asking for their gas and car repair business. He does not go out blindly; he knows where he’s going and who he’s going to make his pitch to. “I case out the business long before I go there,” he says. “I try to find out who’s in charge, and I try to find out something about them … I mean, I’m not going to just walk on up there and talk to David Duke, you know. I mean, I know who I’m talking to.”

Price has no qualms about targeting firms in his district, and there is troubling evidence that he engages in business that is clearly a conflict of interest for him as a county commissioner.

For example, Price’s station currently services and provides all the gasoline for Salvation Army vans used to drive senior citizens to two nutrition programs in Oak Cliff. For that, the Salvation Army collects $30,000 a year from the county. Price votes each year to renew the agreements, while never disclosing that some of the money flows back into his gas station. Confronted with this apparent conflict of interest, Price says he was not aware that the Salvation Army had agreements with the county and says that he would have abstained from voting on the agreements if he had known about them. But, Price adds, he would never shy away from accepting the business, despite his position as county commissioner. If that money has to go somewhere, he believes, it might as well go to African-Americans, who historically have never gotten a fair share of the pie.

“Atlanta built their airport with 50 percent minority procurement,” he says excitedly (actually 25 percent, say city officials). “Within budget. And on time. Fifty percent minority procurement … I want that for DFW. I want that for Dallas County.”

If Price’s numbers are correct—and he uses them a lot—he has increased the total amount of county dollars that go to minority vendors to $9 million from $50,000 since he came to the court six years ago. That has been good for minority business people. And often, it’s been good for Price as well.

One sizable contract—for $700,000—went to a small Dallas engineering firm called Dikita Engineering, owned by an African-American named Lucious Williams. Dikita was hired to do civil engineering work on the new Frank Crowley Courts Building, located next to the Lew Sterrett jail. Williams says that Commissioner Price’s efforts on the court to increase minority contracting made it possible for his firm to get the contract—a fact Price apparently did not forget.

While the Crowley building construction was going on, a county official named Bill Grimes, who is project representative for the Project Management Office, told all his contractors that if anything unusual took place on the job, he wanted to know about it. One day, Lucious Williams came to see him.

“I was told to make a $15,000 contribution to Commissioner Price’s campaign,” Williams told Grimes.

“Did you do it?” Grimes asked him.

“No,” Williams responded.

“Good.”

Grimes told a superior about the exchange, though he made it clear that as far as he was concerned, the alleged demands were hearsay and could not be proven unless Williams stepped forward. Which he did not, although at this point several county officials are aware of what happened, as is the district attorney’s office, which would pursue the matter if Williams came to them with the story.

Williams, asked to comment on the incident, replied: “There are reasons for not discussing it and going off in crazy directions. I think we’re at a boiling point [in this city]. We have to weigh it—the positive and the negative here … I don’t think saying it—it’s the time at all to even say that.”

When asked again for a comment, he said: “I’m not going to tell you John Wiley demanded $15,000 for his campaign. And I’m not going to tell you I told Bill Grimes that, because I don’t remember.”

Ask around, though, and you’ll find people who do remember some of Commissioner Price’s behind-the-scenes demands.

According to a number of business people, black and white, Price’s boycotts and pickets and threats are often tools in a high-stakes game he plays with the Dallas business community. It’s the old trick he learned at Sanger-Harris—scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours—but in a new, much more important arena. Even some of Price’s most deeply principled stands, they say, are tainted by the hustle.

The hustle usually starts with a public complaint, these people say. Price will declare that there has been some wrong inflicted on his community by a certain company—perhaps through an “insensitive” advertisement or a product promotion or a hiring matter. In order to resolve the matter, Price requests a private audience with company officials. That’s where the problems start.

“He never just says he’s going to boycott you, and that’s that,” says one company official who has been in a number of such meetings. “He’ll say, ‘Well, it’s really going to take your doing something for the black community to avert this situation. And these people are looking at me. And if you’re not doing anything for the black community, I can’t help.’” At that point, the company will ask Price what he thinks it should do. And depending on what Price has found out beforehand about that company’s job openings or contract opportunities, he offers a solution. One that often cuts him in on the action.

Southwestern Bell has had numerous run-ins with Price. One of the largest meetings held at his behest took place several years ago at the Top o’ the Cliff restaurant in Oak Cliff. Price was upset because the cover of the new residential phone book depicted an African-American boy in a gimme cap talking into a tin can, while two Anglo children were shown using a modern telephone and a computer. It was clearly a racist slight, Price argued. He wanted to know what the company was going to do about it. Bell had 26 people at the meeting, says someone who was there.

Bell officials have always been quick to respond to Price. They research his complaints, write him letters, and let out new minority contracts. At one point, at Price’s urging, they agreed to hire a minority firm out of Arlington called Sphere Cable. When it came time to renew the contract, the owner of the firm, which is no longer in business, appealed to Bell for help.

According to Bell, the owner stated in a letter that she had been paying Price in return for getting her the contract with Bell. She begged Bell officials not to tell Price if her contract was renewed.

“She said, ‘I just want to pay him for this contract, that’s it,’” says a Bell official.

Price says he’s never heard of a company named Sphere Cable. “If I could ever get my hands on a letter like that, I would sure sue the shit out of them,” he says.

Since that time, according to the Bell official, Price has tried to get Bell to let out at least two other contracts. To him.

He asked that Bell buy gas at his station for its huge fleet of trucks and cars and even suggested that Bell apply for Exxon credit cards for employees who drive company cars. And, on another occasion, he asked that Bell give him the contract for its vending business—all the snack, candy, and soda machines located in the company’s downtown offices and area substations. He and his “brother-in-law,” he explained, had a vending-machine business.

Price has no brother-in-law, of course. He has a former brother-in-law, but Vivian Price says her brother is not involved in any way with vending machines. Says Price’s former girlfriend: “John’s always wanted to go into the vending-machine business. He said there was a lot of money in it.”

“I wish I did have some [vending business] with somebody,” Price says. But he says he doesn’t, and he denies ever approaching Bell about its vending business. He admits that he asked Bell for its fleet business, but only because he and Bell’s chief executive officer, Jim Adams, “are friends.”

Another company that Price has “shaken down,” as its officials put it, is Apex Securities Inc. of Houston, a minority-owned investment banking firm that has co-managed four bond issues for Dallas County over the past three years. Apex was the subject of a shouting match in a commissioners’ court meeting in January, when Price argued that minority companies had been unfairly excluded from a pending $30 million bond issue. The real issue, say Apex officials, is not that Price selflessly wants a slice of the pie for minority firms—it’s that he wants a slice for himself.

While Apex officials say they have never given Price money under the table, they did, after he complained that they “were not doing right by him,” hold a political fundraiser for him in July 1989 that raised more than $8,000 for his campaign.

The fundraiser was held at the downtown Lancers club, and club employees remember it well because after Apex sent Lancers a $500 check to pay for the function, Price called the club and asked for the money. Price said that the check inadvertently had been made out to the club when it was supposed to be a campaign contribution to him. Though the check had already been deposited in the club’s bank, and it was clear there had been no mistake, Price pressed them for the money until they finally sent it to him. Apex had to send the club another $500 check. There is no record of the $500 in Price’s campaign report.

Apparently the Lancers fundraiser did not satisfy Price, because a year later he asked Apex officials for 25 percent of their $75,000 fee from a county bond issue.

“He has said to me that he thought if we made $75,000, that he ought to get his percent of it,” says an Apex official. “He could have meant that as a campaign contribution or he could have meant illegally. I don’t know how he meant it. Either way he meant it, I’m interested in being a player in … business for a long time, and I’m not going to go to a grand jury. Or get involved in some sleazeball stuff to make a living. I mean, I can do business in other places.”

The official said that Apex was excluded from the county bond business for a year after refusing Price’s demand for money. And though Apex was included in the upcoming $30 million bond issue, the official says that Price has retaliated against them by questioning their credentials publicly and privately threatening to take them out of the deal, hinting that he was now favoring another minority firm.

“You’d hate to think that the only way a minority can do business in Dallas County is if the minority commissioner puts his hand on a particular one,” says the Apex official. “What he does is give minority participation a bad name. He’s trying to replace one set of good ol’ boys with a new set of good ol’ boys who happen to be African-American.”

• • •

John Wiley Price is undeniably handsome, polished, suave, articulate, well-read, and, when he chooses to be, incredibly charming. It wasn’t just Dave Fox who was talking about grooming Price to be the first African-American mayor of Dallas. “John has many of the elements that a natural leader would need to unite Dallas back together again,” says another prominent Republican who privately backed the idea of Price for mayor.

But today that man and many other former Price allies are convinced that Price is not the man for the job. They fear that he is hampered by a number of tragic flaws.

Price’s support among city leaders began unraveling last June, at the start of a period known around the courthouse as “The Days of Rage.” At the time, District Attorney John Vance was clearly determined to slap Price with a felony for painting over some liquor and tobacco billboard ads in South Dallas. Price had been prepared for a misdemeanor charge to be filed against him, he says, but he was shocked when Vance pursued the felony. Though the felony charge never materialized, the incident triggered a rage in Price that remains today.

“It just goes through me,” he says. “It just enrages me. I don’t know—I’ve tried to contain it. I can’t. And I know I’m vulnerable with that because you can mention that name [Vance], and I go nuts. He just epitomizes what I think of Dallas and those good ol’ boys. I mean, he is it. Even more so than Henry Wade chewing tobacco, or chewing that cigar, or whatever. I mean, even more so than that. He’s racist to the core.”

In many ways, say people close to him, every stunt Price has pulled since the billboard incident has seemed to be part of some personal crusade to bait Vance—to push Vance into going after him to spark a race riot in his name. That could make Price a hero in the minority community for many years to come.

“The best explanation I can come up with,” says one friend, “is that I don’t think Price has a violent bone in his body. If there’s anything that would satisfy John, it’s not for the revolution to break out and for him to have the opportunity to kill someone, but for him to be killed. That’s the one thing that would satisfy him—martyrdom.”

In his most private moments, Dave Fox has similar fears. How else to explain this year of confrontation? “This is really out of his character,” Fox says. “And he can do so much for the community—black and white. It may be too late. He may get his wish, if he has a death wish. He says he doesn’t. But if that’s true, then what is this?”

Even African-Americans are floating the theory. “John would like nothing better than for a crazed white person to come bursting out of a crowd one day and shoot him,” says a former elected official. “And then we could name a bridge after him and folks down in South Dallas would be in awe of him forever.”

Price does talk a lot since The Days of Rage about dying. He frequently quotes Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X on the subject. He cherishes a framed photo montage made for him by a friend of some of the most famous African-American martyrs. Eerily, his own picture is included among them.

“I guess I try to move somebody to some action,” be says. “It’s just that I believe it. I believe it so much that if it means I’ve got to die for it, I believe it. Life doesn’t mean anything if you stay comfortable. It just really doesn’t. I mean, I wouldn’t make it a second in South Africa. I really wouldn’t.”

He says he’s been in the public eye this year only for one reason: There’s an awful lot to do. “I’m a racer,” he says. “I just don’t know how much time I’ve got, and I’ve got to cram.”

His supporters, though, are beginning to wish he’d slow down. “I really don’t have a quarrel with his heart,” says Ron Kirk, an African-American lawyer with Johnson & Gibbs. “I know that he means well, and perhaps what we’re seeing is burnout—that he may have lost a little bit of perspective because he is frustrated that he hasn’t seen more progress, and that led him down a path that obviously a lot of us in the community feel uncomfortable with. To me, hearing anybody advocate change by violence in 1990 in America is the height of lunacy, of irresponsibility.”

• • •

Violence, as newspaper headlines over the past 20 years will attest, is something that John Wiley Price knows firsthand. He has been accused of publicly striking Justice of the Peace Charles Rose and a lawyer named Christopher Lane. He has physically removed a poll watcher from a polling place on Election Day. And last summer, former County Criminal Court Judge Berlaind Brashear filed a criminal complaint against Price, later dismissed, for threatening to “kick his ass.”

Price’s threatening remarks are also well-known on the commissioners’ court. Last year, County Judge Lee Jackson snapped the microphone off—something Fox says he did often when Price started screaming at someone—when Price protested fellow Commissioner Chris Semos’ motion to approve an innocuous resolution honoring a group of war veterans. Price was angry that none of the veterans who had come to accept the honor were minorities. At one point, Price turned angrily to Semos and told him to take the resolution “and stick it up your ass.”

Price also has a documented history of making his point with guns. In 1972, long before the run-in with officer Robert Bernal, Price was arrested for attempted murder after he allegedly pulled a .22 caliber pistol from his car and shot a man in the right shoulder and the left index finger in a dispute over a woman. Although Price turned himself in immediately after the incident, telling police that he had hidden the pistol along a freeway, he now claims that the gun belonged to the other man and discharged accidentally. Price says he was no-billed by a grand jury. But those incidents, however disturbing, pale in comparison to what at least four women, three African-Americans and an Anglo, say they have experienced at Price’s hands. Three of them accuse Price of rape. The fourth says she begged her way out of a similar fate. One of the four, Price’s former girlfriend, claims she was frequently beaten by him. Price denies the allegations.

None of these women has ever gone to the police to report any of these incidents, and no charge of sexual assault has ever been filed against Price. None of the women would allow her name to be used for this story. All four say they fear coming forward, either because they are afraid of retribution from Price or because the publicity would mean terrible consequences for their careers and home lives.

One woman who says she was raped by Price is a former employee in Price’s office who still works for the county. She says the incident occurred at Price’s home on his birthday last April. Price had held a fundraiser the night before at the downtown Windows club, and the next day, she says, after the campaign contributions collected had been recorded in a ledger, Price asked her to bring him the money, which was about $4,000 in checks and cash.

The woman did not want to go. “He had touched me once in his office,” she says. “He had come up behind me, and he rubbed me on my behind. He said, ‘You know you like that.’ And I just said, ‘You have a problem,’ and I walked out.”

Still, the woman says, she felt obligated to do what Price asked of her. He had given her the job, she says, as a favor to her father, who was an old high school classmate of Betty Culbreath. When she got to his house, though, she left her car engine running so she would have an excuse not to linger.

Price insisted she come into the house. She agreed, but within two minutes, she says, he grabbed her from behind, put her in a chokehold, tore off her stockings, and pulled down her underwear. He entered her from behind, she says, and she never saw his face during the attack. “He’s an animal,” she says, “and he didn’t even sound the same. His voice got really deep and strange. It was like a demon or something.”

No more than 20 minutes later, the woman says, she was back in her car. “I was so shocked that I didn’t think to go to the hospital. I just went home. And I remember my parents sitting in the den, and I had been crying on the way home, and they asked me what was wrong. I didn’t say anything. I took off all my clothes and just threw them in the corner and got in bed.”

To these allegations, Price responds: “That’s an unequivocal lie. And I’ll take a polygraph if you give her one.”

Price also has a documented history of making his point with guns.

The woman has since told her boyfriend, her parents, Judge Brashear, and one other county official about the attack. Brashear, an admitted critic of Price, says he had trouble believing a particular physical aspect of the woman’s story, and told her so. “I did not make an evaluation of whether or not the charge was correct,” he says. “I was going to leave that to the DA’s office. She said to me that she wanted to press charges but was afraid to.”

The other county official says he advised the woman not to press charges because “I thought she was just a little, bitty person and could be really hurt, and when it came down to it, it was her word against his.”

Price’s accuser also told Culbreath about the incident, she says, in June. Her work was suffering, and Price had begun criticizing and belittling her in front of everyone. When she revealed to Culbreath what had happened, she says, the administrative assistant took action immediately. “She said that I obviously needed to leave the office,” the woman recalls. “She said she’d find me another job in the county.”

Which she did. Culbreath, however, says she did so strictly because of the woman’s poor job performance, not because she believed the story about the rape. “I did not believe it, and I don’t believe it,” says Culbreath, who maintains that the rape story came up only after she cited the woman for eight mistakes on the job. “I wrote her up in June, and that’s when this bullshit came up,” Culbreath says. “If that was the truth, why was there nothing said?”

At least one county official, however, says Culbreath specifically described the woman’s transfer as being necessary because of “advances made by John.” Culbreath denies saying that.

A second woman describes a violent, prolonged relationship with Price. When she was approached for this story, she agreed to talk about her relationship with Price, but only on the grounds that her name not be used because she now has a good job and is happily married.

She says her entire relationship with Price was abusive and that over the course of several years, he struck her repeatedly and often forced her to have sex against her will. Often, she says, he would pin her to the bed and beat her on her thighs and buttocks until she cried. One time, she says, he left such a serious bruise on her thigh that she canceled a doctor’s appointment to avoid being asked questions about it.

“Looking back I realize how stupid I was because I talk to women all the time who take the abuse, and before I went out with John, I never understood it,” she says. “Now I do. He never did anything where he disfigured me, but he was physically abusive and then very apologetic. He can snap like that.”

“I don’t even believe you’re asking me about shit like that,” Price says when asked about the woman’s story. “It’s so damn wild. The stuff is wild. I mean, it’s wild.”

Fifteen years ago, while Price was separated but not yet divorced, he doggedly pursued an Anglo woman he met at work. Though she spurned his advances for months, his repeated requests for a date finally wore her down. “He was a very charming man,” she says. “Very nice. Very friendly. And I was trying to be the unbiased, unprejudiced person trying to get to know blacks more.”

They saw each other once, she said. She invited him to her apartment, which she shared with her two children, for a glass of wine. But to her shock, as soon as he came into her apartment, he accosted her. “He did rape me, and it did happen,” she says. “I would not have allowed it at all—I would have somehow gotten out of the apartment if my two kids were not asleep in the apartment. I was concerned about what would happen to them.”

Although she was outraged, she did not go to the police, she says, because her children and her mother would have been shocked and upset to learn that she had even invited a black man into her home.

When she was contacted for this story, the woman said her anger had long since dissipated, and if she were to come forward now it would only “disrupt my life at a time when I really don’t need it.” Still, she added, “I’m having trouble with myself for not coming forward … Here I am in a position to do something.”

When asked to respond, Price says. “You know I don’t drink, that’s No. 1. I mean, you know, give me a break.” Pressed to answer yes or no to the question of rape, he says, “Give me a break.” Asked again, he says, “I don’t even know why you’re asking me anything.”

Another woman, another former employee of Price’s, says he came to her apartment one night when she was still working for him to return some money that he had borrowed to buy tickets for a political function.

Price asked to see her apartment and, thinking nothing of it, she showed him around. When they got to the bedroom, she says, he grabbed her and pushed her on the bed, pinning her down. He began groping her, but she twisted away from him and ran into the bathroom and locked the door. When she realized that he wasn’t going to leave her apartment, she came out of the bathroom and tried to act as though nothing had happened. This time, she says, Price pinned her to the kitchen floor. The whole time he was on top of her, she says, he was like a man possessed. “His eyes were red, and his face was all contorted,” she says. “He had a gravelly voice that wasn’t natural at all—it was real scary … I started crying, and I was pleading and begging and pleading, and he finally let me go. When he got up and went to leave, he laughed it off. He said, ‘Hey, you know I was just kidding.’”

The woman doesn’t believe that Price was kidding. “I don’t think he likes women,” she says. “I don’t think he likes women at all.” The woman says she never considered going to the authorities about the incident. She did decide to leave her job, though, and she is now successfully employed elsewhere. She says any woman would be a fool to pursue criminal charges against Price.

“John Wiley Price can get any number of credible witnesses to say, ‘Why does this man have to rape this woman? He has plenty of women throwing themselves at him,’” she says. “And it would be true. He knows that.”

Again, Price has little to say about the woman’s story. “I’ve done nothing like that,” he says.

Sexual assault is a very serious charge, one that has not been formally lodged against Price and might never be. At this point, no one is willing to discuss it on the record. But the people who work around Price at the commissioners’ court are starting to hear about the allegations. In fact, one county official was recently informed, on a confidential, FYI basis—in case legal action was ever taken—that Price had, on several occasions, cornered other women employees (“literally upon being introduced”) in a stairway or elevator and fondled them.

• • •

Zan Holmes, Price’s pastor at St. Luke Community United Methodist Church in South Dallas, is dressed impeccably, as usual. He peers through his rimless spectacles soberly, hands folded in his lap, and admits that he has been worried about John Wiley Price this past year.

It’s not his church-going that’s the problem, Holmes says. Price has always been one of the “early risers” at St. Luke’s, attending the 3 a.m. service and traditionally being the first to arrive. He grabs a collection basket when the ushers need a hand; he gives up his seat when he sees that women or elderly people have to stand; he clothes the needy; he aids the sick.

Bu outside the church—out there in the world that Price finds so unjust—he has not found himself to be so charitable. He has been impatient and inconsolable. He has done things that Holmes could not understand, like putting a gun to an off-duty police officer’s head. As a result, people who have always supported him—people in Holmes’ parish—are starting to feel uncomfortable. “A lot of his friends don’t like to see him do some of these things because they don’t want to lose him over what they consider to be a minor issue,” Holmes says carefully. “John is a smart, bright, capable person who has the energy to go along with that. And they don’t want to see that wasted because of something minor like breaking a windshield wiper. And who say to him, ‘Let other people do that if it becomes necessary. We need to save you for major battles.’” But Price does not seem inclined, if the last 12 months are any indication, to save himself.

Holmes likes to think that his friend’s eruptive, erratic behavior stems from a struggle he may be having to develop a personal theology and philosophy of life. Meaning, Holmes says, “his understanding of God and life—and his purpose in the midst of that. Martin Luther King Jr. had [that understanding]. Malcolm X was developing it when he died.”

If Price doesn’t find it soon, Holmes concedes, it may be too late. Not for Congress, which the popular press loves to speculate about. Not for a state senate seat or statewide office.

At this point, after such a volatile year, John Wiley Price’s own campaign treasurer, Holmes, is deeply worried about something far more mundane than Congress.

“I think a major concern is the commissioners’ court,” Holmes says. “I think there are people who realize how vulnerable that position is. And he has the ability to function extremely well in that position and do a lot of good.”

He pauses and sighs, in spite of himself. “That always gets lost in this other stuff.”

40Gr8

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author