Mike Wilson likes to think back on his career. Most of it,that is. During the six years he spent with the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office, from 1971-74 and 78-81, he lost a few, but not many. Some of his cases were grim, but some were full of human comedy. There was the High-Class Madam case, in which a procurer named Sherry Blanchard kept a little black book filled with the names of the well-to-do men who used her service. Wilson laughs, remembering the star witness who had slipped a Mason jar of wine into the witness room, somehow ending up with a black eye while waiting to testify. Despite his witnesses’ shenanigans and the reluctance of her customers to testify, Wilson won.

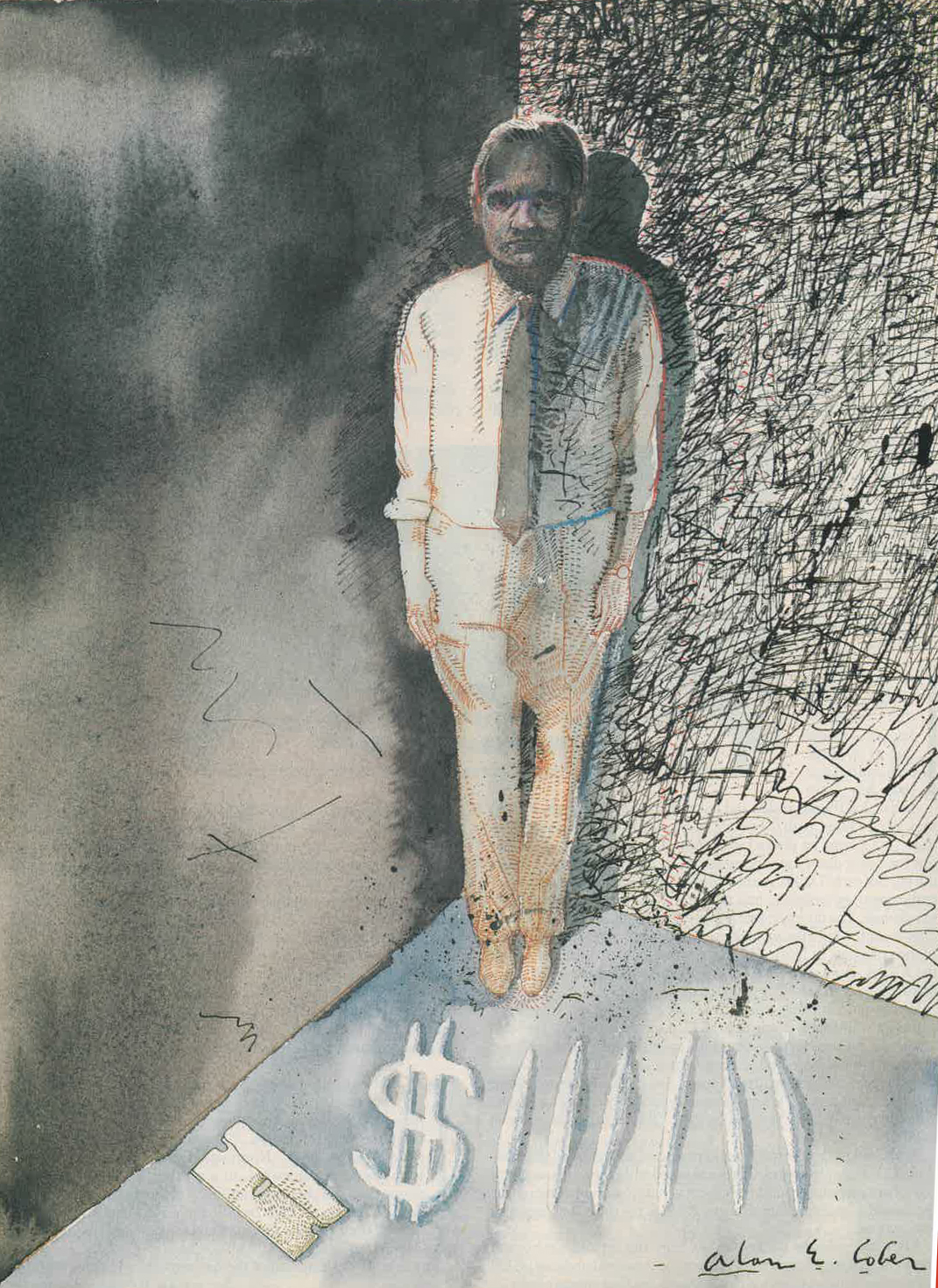

And there was the infamous Debbie Does Dallas case. Again Mike Wilson laughs. Although he privately felt that prosecuting dirty movie cases was a waste of time, he held the jury’s rapt attention as he presented evidence that the film, which depicted a remarkably agile young woman intermittently dressed as a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader, was obscene. Mike Wilson had a way with juries. He prosecuted murderers, rapists, and drug dealers, in the process earning a reputalion as an excellent-and immensely likable-prosecutor. At forty-six, his face seems gray, more lined and worn than a man’s his age should, but it’s still not hard to imagine Wilson in a crisp white shirt and expensive three-piece suit, his dark, wavy hair showing distinguished streaks of gray. You can imagine him striding in front of a jury box, commanding the panel’s attention, making them listen to him, like him, believe him.

Today, however, it’s considerably harder to believe Mike Wilson. He’s leaning against the wall in a stark holding cell at a prison facility in Mansfield, south of Arlington. He’s wearing scuffed tennis shoes and a bright orange cotton top with “Mansfield Jail” branded across his back. Sitting on the floor beside him is attorney Christopher Milner, who once worked side-by-side with Wilson in the DA’s office.

Milner is not Wilson’s co-prosecutor today. Instead, Milner and his partner Tom Mills are defending Mike Wilson against charges that shock even his closest friends. Wilson sits in jail, awaiting trial in late November for accepting twenty-one pounds of cocaine in lieu of legal fees. His arrest in March by agents of the Drug Enforcement Agency stunned those who knew him, though they were aware that his behavior over the last few years had become increasingly erratic.

The tale took a stranger twist when it was discovered that Wilson, at the time of his arrest, was driving a Porsche owned by Joy Aylor, a North Dallas woman charged with hiring a hit man in the brutal murder of her estranged husband’s mistress. And the story turned downright bizarre when Wilson and Aylor, both facing imminent trials, disappeared together. Wilson-shattered, alone- was arrested by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in British Columbia, and returned to Dallas, where he admitted to a judge that he was a cocaine addict.Lawyer says drug use led him to flee

The spectacular self-destruction of Mike Wilson has left desperate clients scrambling for other attorneys, and those closest to him struggling to understand what happened. How did a man of such skill and integrity fall so far, so quickly?

The answer may lie in the peculiar world of criminal defense attorneys who specialize, as Wilson did, in representing drug dealers-a world one lawyer describes as “seductive,” replete with expensive cars, flashy women, and lots of money. And a world of paranoia, fear, even danger. Mike Wilson, who spent years putting bad guys behind bars, now found himself terrorized by some of his clients and their associates: he claimed to have been robbed of $30,000 in cash at his home by men wielding machine guns, and says that one of his clients, a major drug dealer with connections in Colombia, threatened to have him killed. Ironically, he also found himself a target of those in law enforcement who had once admired him.

Wilson, who long had struggled with his own personal demons, was sucked into the abyss-an abyss that may cost him not only his profession, but decades of his life.

•••

If nothing else, growing up in Winnsboro, a small East Texas oil town, gave Mike Wilson a lifetime supply of one-liners. “There were forty-seven people in my graduating class,” he says. The town was so small, “we took turns being the village idiot.”

But his childhood was positive for other reasons. The pace of life in Winnsboro was relaxed and free of pressure. The Wilsons literally lived on Main Street, which meandered through the center of town. His father, one of the last of the wildcatters, ran an oil drilling company. “One year we’d have a plane, the next, just a couple of cars. We never went hungry, though.”

Wilson, of course, was the quarterback for his high school football team. “They needed someone smart enough to remember the plays,” he says. “We only had about five. I liked to get dressed up in the uniform, but I wasn’t crazy about getting busted up. My mother said I wasn’t a great football player, but I always looked good losing.”

During the summer before his sophomore year, Mike met Lucy Brants, a petite blonde from a well-to-do family in Fort Worth. He describes it as love at first sight. They married in 1965, still in school. One of their first dates, however, turned into a disaster when Mike was bitten by a water moccasin while water skiing with Small and his date. Small rushed him to the hospital, where he stayed for several weeks, his leg black to the groin.

It was not the first time that Mike Wilson fought the odds. When he was a freshman in high school, he had been run over by a hay wagon while Christmas caroling. His weight plummeted from 150 to 90 pounds; for eight months, he had a colostomy. Remarkably, he bounced back, not even missing a football season. Mike also recovered quickly from the snake bite. Small, impressed, knew that Mike Wilson was “one tough cookie.”

But Wilson had another problem in college that would prove much harder to conquer. “Phi Delts were all known for a little too much drinking,” says Small. Mike was no exception.

In 1969 the Wilsons and their first son Michael moved to Dallas. With the Vietnam War escalating, Mike had to stay in school or risk being drafted. The decision that actually took him into law seemed surprisingly casual to many who knew him: a fraternity brother was going to SMU law school, so Mike decided he’d go too. The move puzzled all his friends, but he knew early on he had made the right choice.

During his last year in law school, while taking advanced criminal law, Mike spent an evening riding with a police officer on his i beat. He was stunned by the violence he saw. Then Jim Barklow from the DA’s office came to talk to his class. The law-and-order prosecutor steamrollered the liberal professor, making a lasting impression on Wilson.

After graduation in 1971, Wilson, now the father of two sons, went to work for the District Attorney. From his first day, when he found himself in the courtroom on a jury trial, he began building a reputation as an , effective, tough, fair prosecutor.

“Mike made a good appearance,” says Doug Mulder, who was DA Henry Wade’s right-hand man at the time. “He was very knowledgeable of the law. To be a good trial lawyer, you have to be aggressive, competitive, industrious. But most of all, you have to be able to win. Mike had that.”

Virgil Melton Jr., now court coordinator for the 265th District Court, worked for years as Mike’s investigator. “He was very conscientious,” Melton says. “He’d go to the crime scene, talk to witnesses. He always had time to talk to the victims, to reassure them he hadn’t forgotten them. He had a terrific recall for names and dates.”

Judge R.T. Scales appreciated Mike’s ability to evaluate a case and determine if it should be a plea or go to trial, “He was very ’ good in front of a jury-direct, to the point, and very sincere,” says Scales, who is now retired.

Melton agrees: “Some of his final arguments could bring tears to your eyes.”

Defense attorneys liked him because he played lair, but that didn’t mean he was a soft touch. “Mike was a tush hog,” says one undercover police officer who worked frequently with Wilson. “You didn’t cross him. He was 110 percent to the floor when he was prosecuting.’” During a recess in one trial, a defense attorney confronted an officer who had testified against his client, claiming that the officer had lied in court. Mike slammed the attorney up against the wall and started yelling: “Don’t you call my witness a liar!”

Wilson seemed to thrive in the courtroom. If he hadn’t tried a case in a while, he began to get antsy, irritable. His wife would say he was impossible to live with. “Why don’l you try something?” she’d ask. “I liked being the star,” Mike admits. “Trial work is the last blood sport left to us.”

But in 1974. he left the DA’s office to join Bob Fain and Tommy Callan, also prosecutors, in private practice as a criminal defense attorney. Promotions at the DA’s office were slow, and there weren’t as many courts then as now. Mike felt stymied because he couldn’t try the high-profile death penalty cases reserved for the two or three most senior prosecutors like Doug Mulder and Jim Barklow.

The move was a disaster. “I left too soon,” Mike says. “I didn’t like it and didn’t do well at it. I felt there ought to be a relationship between how talented you are and how successful you are.” To Mike, building a profitable private practice seemed to depend not on performance in the courtroom, but on how well he curried favor, garnered court appointments, and squeezed money out of clients. And there was another problem: defense attorneys are supposed to keep their clients out of the courtroom. Mike missed the trial work, being the star. And maybe he just didn’t give it enough time. “Some of my problems,” Mike admits, “come from the fact that I like instant gratification.”

In 1976, his drinking, exacerbated by his unhappiness with work, led Mike to check into an alcohol treatment center. After a stint there, he reevaluated his career and decided to attempt a return to the DA’s office. “I was in favor of it,” Mulder says. “I think he missed the action. His drinking problem was well under control. It didn’t affect his work.”

But it remained a problem. All told, Mike checked into an alcohol treatment center five or six times during the Seventies, but always returned to his old habits. Perhaps it was inevitable; his father, grandfather, and brother were all alcoholics. Mike might have continued that pattern for years, but something happened that he couldn’t ignore.

Wilson had stayed at the DA’s office until 1981, then left again, this time for a position in the civil law department of the Katy Railroad. It was a good opportunity, but an incident in October 1981, at a seminar with other Katy lawyers, ended that career move. “Mike made the mistake of taking a drink,” says Fred Davis, a Bryan, Texas, attorney who had befriended Mike at the DA’s office. After getting drunk and making a scene, he was fired. Soon, he and Lucy were having marital problems. “Up until the Katy Railroad incident, I don’t think Mike understood about alcoholism. He believed he could still drink under guarded circumstances,” Davis says.

Mike checked into Westgate Hospital in Denton for thirty days. This time, he got the cure. “To this day, I have not touched a drop of alcohol” Mike says.

Returning to private practice, Mike was almost immediately successful, staying on the wagon with the help of an Alcoholics Anonymous chapter made up of lawyers. “He was one of their stars,” says Davis. He frequently gave talks about alcoholism to other groups and was seen as a shining success story. During the early Eighties, Mike began working with John McShane. “Both represented lots of professionals who had problems with alcohol and substance abuse. They were very successful at it because they understood it,” says Davis, who adds that both attorneys frequently steered their clients toward recovery programs as part of their rehabilitation.

In the mid-Eighties, Mike’s practice was thriving. His struggles with booze and his profession seemed to be behind him, and he was enjoying the fruits of his labor. He was living in a home worth well over $300,000 on the shores of Eagle Mountain Lake in Fort Worth, commuting to Dallas in a 924 Porsche. In just a few years, he had gone from being a prosecutor making $55,000 or $60,000 to a criminal defense attorney making many times that. When the seeds for what came later were sown is debatable. But it’s clear that as his clients-mostly drug dealers-prospered, so did he.

And then the rumors started.

•••

Mark Hasse was surprised. For several years, he had watched Mike Wilson prosecute as well as defend the accused. Now, they were facing off, and Wilson seemed to be.. .well, distracted. It didn’t seem like the Mike Wilson he knew.

In January 1987, Hasse was chief prosecutor of drug cases in the DA’s office, on special assignment to try a case in Rockwall. Mike was defending Tommy Lee Hass, who was accused of operating a speed lab. “He came over on the Hass case totally unprepared,” Hasse says. “Wilson has the trial skills, but he wasn’t getting the job done. He wasn’t asking the right questions. He just couldn’t get it in gear.” Hass got life in prison (although the conviction was later overturned due to problems with the search warrant), but Hasse was troubled by Mike’s lackluster performance.

Friends put his strange behavior down to marital problems. He and Lucy had been through numerous struggles, including his alcoholism and her serious health problems. Mike’s apparent devotion to her during her illness touched those who worked with him. During the mid-Eighties, however, their marriage disintegrated. In July 1986, they separated, beginning an acrimonious divorce battle that lasted two years.

“Mrs. Wilson was bitter that he left her and moved to Dallas and dropped all that debt on her,” says Winfred Hooper, her divorce attorney. (Lucy Wilson, now attending law school in Houston, declined to comment.) Mike negotiated a temporary support order obligating him to pay $12,500 a month to his wife and children; his oldest son was attending college, but his two younger boys were still living at home.Murder-for-hire defendant flees state

Mike quickly fell behind in the support payments and came close to being held in contempt of court four or five times. Once he was briefly jailed for non-payment. Mike submitted a document in July 1987 showing that his monthly expenses came to more than $20,000, but his monthly income was now only $14,000. He was making payments on the house, a 1986 Porsche, Lucy’s 1986 BMW, a 1986 pickup truck, and a ski boat. (Other assets included a 1972 Rolls Royce, a Datsun 280Z, a Suburban, six shotguns worth $12,000, four handguns worth $1,000, and a Rolex watch valued at $3,000.)

Aglaia Mauzy, who represented Wilson, says that part of the problem was the new RICO (Racketeer-Influenced and Corrupt Organizations) statutes and federal sentencing guidelines that had recently gone into effect. More rigid sentencing rules meant fewer returning clients. And the government began pursuing the money that drug dealers paid to lawyers, seeking to represent them as drug profits subject to seizure.

Though he apparently never lost money this way, Wilson was fearful that the government would investigate his earnings. When deposed in the divorce lawsuit, he refused to provide documents or answer questions about his income, invoking the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrim-ination. Several lawyers speculate that he was worried about an Internal Revenue Service investigation. One client says Mike refused to accept anything but cash.

“Mike was struggling to stay abreast of his financial obligations,” says Fred Davis, who saw Wilson frequently during hunting season. “He was despondent over that. I don’t know whether his problems with drugs are attributable to that.”

And Mike had other problems as well: dangerous clients. In the early Eighties, he began representing a Dallas drug dealer named Hollis Burns. Burns-a gambler and a pool shark-would go to Colombia three or four times a year in the late Seventies, bringing back cocaine on shrimp boats. His take was $60,000 to $80,000 per trip. He had an enforcer named Rambo, who had blown up a California service station at Burns’s request.

Burns hooked up with Michael Dawson, a northern California rancher in his mid-thirties who would fly to his ranch loads of cocaine weighing anywhere from 15 to 100 kilos at a time from Florida, then distribute it to Los Angeles, Dallas, and other major cities. He had connections with the Ochoa cocaine family in Colombia.

The DEA began investigating Dawson in California, and shortly before the operation became overt. Burns advised Dawson to move to Dallas. He told him he had a lawyer with “juice” who knew when things were hot, where investigations were going. His lawyer’s name was Mike Wilson.

Dawson took Burns’s advice and bought a nice house in North Dallas. The two drug dealers lived (heir version of the high life, taking over the VIP lounge at the Million Dollar Saloon and spending thousands of dollars a night. “Mike was on retainer to them,” says one associate whom Mike represented. He says Mike frequently sat in on “business meetings” between drug dealers. “He was able to get valuable information, tell them what was going on around town.”

But in 1986, when the DEA went after Dawson. it apparently was a surprise to everyone. Dawson was arrested after a highspeed chase, when he leaped from his car carrying his preschool daughter in front of him as a shield. In his car. in addition to his prostitute girlfriend, DEA agents found a gun and $354,000 in cash.

Dawson was extradited to California to stand trial, and Mike began traveling back and forth to represent him. Burns too was arrested, charged with possession of cocaine with intent to deliver, possession of an illegal gun silencer, and solicitation of murder for attempting to hire someone to kill Dawson’s wife’s boyfriend. After making bail, he was arrested again. Then, after his release, Bums vanished.

Meanwhile, Dawson fumed behind bars. As his lawyer, Mike tried first to cut a deal with a Dallas narcotics agent he knew, promising that Dawson would “flip” a bunch of Colombians in return for leniency. His offer was passed up the ladder, but neither the DEA nor the FBI would talk to him. Wilson tried the DEA in Sacramento and in Washington, D.C. No go.

The Dallas officer says he believes the DEA wouldn’t cut a deal because they were convinced that Mike was “dirty.” “You can’t tell me they weren’t interested in nailing some Colombians,” the officer says. But under federal rules, any discussion with Dawson would have to include Mike, who, it seems, was tainted in the eyes of the DEA.

Mike had helped persuade Dawson to plead guilty to five federal drug charges, indicating his willingness to work with the government. But no matter how hard Wilson tried, no one would make Dawson a deal. Wilson began saying that Burns was the big dealer, that Dawson could flip him. Again, no deal. The rule of thumb in law enforcement is you must trade up the scale, from smaller dealers to larger ones, not down. And no one believed Burns was the big guy.

Burns, who had fled to Rio de Janeiro, began hearing what his attorney was saying about him. Threats against Wilson began filtering back to the States. “It was not smart,” says a lawyer close to the situation. “Wilson was in deep shit at that point. He was dealing with a major player.”

During that summer of 1987, Mike was fighting Lucy over the terms of their support agreement. But his troubles with Dawson made the divorce trauma pale in comparison. He hadn’t been able to make a deal for his client, and he was scheduled to appear in Sacramento on July 2 for Dawson’s sentencing. The case, the biggest DEA bust in northern California history, was gathering enormous publicity.

But on July 2, Mike didn’t show up. The federal judge, irritated, set another hearing for July 16. Again. Mike failed to make an appearance. Enraged, the judge demanded that Wilson show cause why he should not be held in contempt of court and jailed.

On the third sentencing date, August 13, Mike finally appeared in court, carrying affidavits from two doctors, who said he was under their care for prostatitis as well as a bleeding peptic ulcer. His story was convincing; Mike looked terrible.

“When I met Wilson,” says a DEA agent in Sacramento, who asked that his name not be used, “he was a shell of a man-completely a nervous wreck. Every time we saw him. he looked worse than the time before.” Even the police officers, who have little fondness for drug dealers’ attorneys, started feeling sorry for him. “We all quite frankly thought Mike was a candidate for suicide.”

“It was totally nuts,” says the DEA agent. “We investigated it to death. We told Wilson, ’What are you worried about? It’s just another desperate defendant.”

But Wilson was terrified. He indicated to a Sacramento Bee reporter that he believed a contract was out on his life. ’Tve been threatcned, I’ve been called, I’ve been told four times since August 13, ’Don’t give Dawson up or you’re a dead man,”” Wilson said.

Shaky, sweating profusely, Mike got on the stand and testified that though he had tried, he hadn’t been able to make any deals for Dawson. And there had never been any suggestion about a deal with the CIA. Though his voice never wavered, he seemed to be facing a firing squad. “I thought the guy was going to collapse,” the DEA agent says. “He walked into the hall and literally had to sit down. He said something real dramatic, like I’m dead now.” We all thought he was overreacting.”

Perhaps Wilson had heard and seen things that convinced him Dawson, even behind bars, could reach out and crush him. And Bums was still at large. “No matter what happens to Mr. Dawson or Mr. Bums, I will spend the rest of my life as a marked man,” he told the Bee reporter. “I’ve lost my life, my [law] practice; I’m snuffed.”

In retrospect, friends wonder if Mike truly , was in danger, or if he was using drugs that , made him paranoid. Whatever the case, the . judge didn’t buy Dawson’s version of events. ; His motion for a new trial was denied, and the drug dealer was sentenced to seventy-seven years in prison. (Hollis Burns was ultimately tracked down in Brazil, extradited, and sentenced to six years in prison.)

“After Dawson, Mike just flat disappeared,” says an assistant district attorney. “You couldn’t find him in the courthouse for months.”

Slowly, Mike resumed his practice. But the word was out. “There comes a point where a lawyer is beyond just representing his clients,” says Mark Hasse. “And by 1988. it was clear to most of us that Wilson had gone over the line.”

On February 24, 1988. Mike and a client named Marty Dean Young, who was on probation for possession of cocaine, were arrested in Wilson’s red Porsche during a traffic stop in Garland. Police found one of Mike’s guns and a bag with cocaine residue in the car. One officer, an old friend, talked to him that night.

“He was wasted,” the officer says. “He had probably lost fifty pounds, He talked real weird, like he had nothing left in his nose. He was so embarrassed at being in jail in front of guys he had worked with.” Because the Garland police couldn’t prove which of the men the dope belonged to, they filed no case against him. And they knew the DA’s office wouldn’t take a case against a lawyer unless they could nail him to the wall.

At some point, however, the DEA moved beyond targeting Mike’s clients and potential clients, They began looking for a way to bust Mike Wilson himself.

•••

At about 8 PM on the evening of March 20, 1990, Wilson and a friend and client named John Sennett White, a Vietnam war veteran and an associate of Hollis Burns, visited the Holiday Inn on North Central Expressway. They entered Room 909. After covering the smoke alarm with a towel. they dimmed the lights and turned on the television. Taking out a lighter for illumination, they peered into an aluminum suitcase that had been left in the room earlier.

The next morning, Mike returned to the hotel carrying a canvas bag. Moments after entering Room 909, he left again. As he walked toward the parking lot, a handful of armed DEA agents descended on him. Mike was arrested and booked on two federal drug charges. In the bag; twenty-one pounds of cocaine, with an estimated value of $242,000. A little later, DEA agents also arrested John White as he tried to enter the room.

Mike was charged with taking the cocaine in lieu of legal fees to represent thirty-year-old Mark Monroe Northcutt. Known in gyms around the state as a steroid dealer, Northcutt was a body builder and power lifter who had been arrested six months before in Houston for possession of twenty-five kilos of cocaine. After his arrest, he had called a Dallas body builder named John Hoffman, whom Mike was representing on steroid charges, and asked his opinion of Wilson, apparently at the instigation of the DEA. “I loved Mike,” Hoffman says.

Northcutt agreed to set up Wilson. He made audio tapes of conversations with Mike, saying that he wanted the lawyer to represent him, but he had no money, only “product” that Mike could use. On one tape, Mike reportedly says, “I can’t do that; then I’d gel in trouble, too.” During a phone call Northcutt taped with Hoffman, Northcutt complains that he can’t get Mike to come to Houston or answer his phone calls.

Wilson, meanwhile, had asked another body builder friend. Keith Rowe, his opinion of Northcutt. Rowe told him: “A con from the word go.” He warned Mike to be careful. “When [Wilson] was arrested, I knew instantly it was Northcutt, working his case off” Rowe says.

Rowe says he can believe many things about Wilson, but not that he intended to sell the cocaine. “He wouldn’t deal drugs- never,” Rowe says. “But he got screwed up on that shit.”

Wilson’s attorneys permitted D an interview with him in jail, but limited the questions to background information. But according to The Dallas Morning News, Wilson told a judge that he began using cocaine in 1987, when he was going through his divorce and rattled by his fear of Dawson.

According to Dr. Robert Powitzky, a psychologist who examined Wilson in jail, Mike says he first used cocaine in 1987 while visiting John White at his home. “I was bored,” Mike told the psychologist. “I’d never tried cocaine. When he offered it, I took it.”

Powitzky says that within seven to nine months, Mike was using cocaine daily. He frequently would go on five- or six-day benders-not eating, not sleeping, snorting coke five or six times a day, then zonking out for a few days at a time. “Those stretches make you lose all sense of reality,” says Powitzky. The day he was arrested was the fifth day of a binge. A DEA agent told Mike they had wondered if they would bust him before he died.

Friends at the courthouse noticed that he looked sick, “like he had AIDS,” says one assistant district attorney. Even Fred Davis, in Bryan, began to wonder what was wrong, During bird-hunting season in the fall and winter of ’89 and ’90, Mike fell out of touch. “That wasn’t like him,” Davis says. “He became evasive, There was always some reason he couldn’t go hunting.”

Davis, aware of the situation with Dawson and Burns, had urged Mike to get into another area of law. “It was too risky, too dangerous,” Davis says. “Your client is dangerous to you. Your friends’ clients are dangerous to you, because of what the lawyer knows. You can’t trust anybody. He began to think people were tapping his phone.”

And face it, Davis says, the life can look appealing. Mike suddenly found himself in a young, fast-lane crowd. “A lot of drug dealers are very attractive,” agrees defense attorney Jim Johnston. “They are bright, fearless; they live on the edge. They have a lot of attractive women hanging around. They’re real pirates in the classic sense, who love the excitement. It’s real seductive.”

Perhaps Mike simply lost his moral compass. “There’s an inherent evil in being a prosecutor, then going the next day into private practice,” says assistant DA Cecil Emerson. “One day, you’re wearing a white hat, doing the right thing. You have all these illusions of being Perry Mason. The truth is, 95 percent of your clients are criminals. All of the sudden, they become your associates and friends. It’s easy to get sucked in.”

If anything could have stunned his friends more than Mike’s arrest on drug distribution charges, it was the revelation that he was involved with Joy Aylor. a wealthy woman about to stand trial on capital murder charges. Out on $140,000 bond, she had been indicted in 1988 for hiring a hit man to murder her estranged husband Larry’s mistress, Rozanne Gailiunas. in 1983. The murder was brutal; Rozanne was found naked, tied to a bed, with tissue stuffed down her throat. She was strangled and shot in the back of the head while her four-year-old son was in another room.

Aylor also had been charged with hiring somebody to kill her husband. Larry Aylor was unharmed, but a friend was shot in the elbow when they were ambushed at his ranch in 1986. The schemes unraveled after an anonymous tip to investigators. If convicted, Joy could receive the death penalty.

Joy and Mike had first met in May 1989, through a cousin who was undergoing a divorce and was being represented by attorney Denver McCarty, who had shared an office with Mike. Their contact was casual at first; Aylor would call him every other week.

On December 26, all that changed. Joy called Mike, upset. Her nineteen-year-old son Chris had been in a fiery accident in his new Corvette that evening. She wanted Mike to go to the hospital with her. At the emergency room, they were told her son had died. Joy asked everyone but Mike to leave her son’s bedside, where he comforted her as she sobbed and cried, talking to her dead son.”It was an intense experience for Mike,” says Powitzky, who spoke with permission from Wilson’s attorneys. “They bonded.” From that night on. they were inseparable.

As quickly as Wilson had become addicted to cocaine, he became obsessed with Joy Aylor. Part of Joy’s appeal to Mike was her tolerance of his drug habit. “She’d stay up all night with me,” Mike told Powitzky. Joy would drink, occasionally using drugs, while staying sober enough to take care of Mike.

The day before Mike’s arrest, a friend had visited John White’s house. “It was weirder than I’d ever seen,” he says. Mike. Joy, and White were sitting around playing dominoes, apparently high on something. “No one said a word for thirty minutes. I finally left.”

Joy’s trial was set to begin on May 14. Mike, out on a no-cash, personal recognizance bond set by U.S. Magistrate John Tolle, was scheduled to go to trial in June. For months, Joy had been saying she would never go to trial. She talked of gassing herself and began carrying around razor blades with which to slash her wrists. She spoke of going to Mexico or Canada, and began liquidating her assets to gather cash. Mike was worried that she might leave, but her plans were always vague.

Rapidly, Mike Wilson’s world came apart. He had stopped using drugs after his arrest, but now he discovered that his father had cancer. For a lifetime, they had carried on a love-hate relationship, but in the last two years, they had reconciled. Now, his father was dying. Mike’s second wife Mona, whom he had married in February 1989, had filed for divorce. His youngest son was now living with his mother in Houston. All he had was Joy. He began to slip into depression. On a Friday in early May. Joy called him, upset because she had discovered that what she thought was a bond hearing on Monday was actually far more serious. She was definitely leaving the country. And Mike, who later described it as “stepping off a cliff,” decided to go with her.

Joy, Mike, and her cousin Brad Davis left Dallas on May 4, headed north. Joy was carrying at least $300,000 in cash. Mike bought a Jeep in Wyoming under a false company name. Davis returned to Dallas, and Joy and Mike traveled into Canada, registering at hotels under the name “John Storms.”

A little more than a month later. Bob Fain, Wilson’s former law partner who now lives in Montana, received a call from Mike, who didn”t say where he was. “He sounded like someone who wanted to come in from the cold,” Fain says. “I felt suicide was a serious possibility.”

Fain talked him out of considering that as a solution, “I made arrangements with the FBI for a turn-in point at Billings. I would have made it closer if I had known he was in southern British Columbia.”

Whether Mike realty would have turned himself in is unknown. Joy definitely was not interested in doing so. For three weeks, they had lived in an apartment near Vancouver. But the farther Mike got from Dallas, the clearer his thinking became. Joy, on the other hand, began getting “manicky,” Powizky says, and schizophrenic. Mike told the psychologist that Joy rambled on about the murdered Rozanne Gailiunas. saying that “she deserved it,” and talked about the possibility of having her own sister killed. Her words chilled Mike.

After three weeks underground, Joy had called a friend in Dallas and learned that Brad Davis had been arrested and charged with perjury for telling police he had left the two in Denver. Afraid that he had revealed their whereabouts, Joy decided to fly to Mexico. Mike had made up his mind; he was going back to Dallas. He claims that he led her to believe that he would follow and arranged for her to leave a message for him at a hotel in Vancouver, when she had made it. Joy flew to Mexico on June 7.

Several days later, Mike called Fain to set up a turn-in point. On June 12. Mike was arrested at a resort about 300 miles outside Vancouver by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, after calling a hotel he had stayed at earlier and asking if Joy had called for him. He left a forwarding number, which the RCMP (raced. According to Powitzky, Wilson says he had decided by that point to turn Joy in and wanted to know where she was. (At press time, Aylor remained at large.)

Mike was quickly returned to Dallas, where he discovered that during his absence, his father had died. He testified at a bail hearing that cocaine had marred his judgment; “It [cocaine] was something that was impossible for me to put down.” Magistrate Tolle, no doubt embarrassed that Mike had jumped the no-cash bond, declined to set bail.

Attorneys watching Mike’s situation say that unless Mills and Milner pull off a miracle. Wilson is sure to spend time in prison if convicted. “Wilson is unlucky he’s in the federal system,” says Hasse. “That system is hard on large-quantity drug dealers. This is not even a close call for probation.”

According to documents filed in federal court. Wilson’s attorneys apparently will hinge their defense on portraying him as a walking vat of chemical soup. Over the years, during treatment for emotional problems, back surgery, and other physical ailments, Mike has been given numerous pain-killers, anti-depressants, and psycho-tropic drugs. Cocaine was simply another drug to ease the pain, they are likely to say. And once addicted to cocaine, they will argue, how could Mike make rational decisions when it came to deciding whether to leave that cocaine in the hotel room?

Davis, for one. doesn’t think he could. “Once he used drugs the first time, he lost the power of choice,” Davis says. “It became an obsession. He was more vulnerable to it as an addictive personality.”

But Hasse thinks Mills and Milner are going to have a hard time with the theory that drugs made him do it. “This is not a guy who has a little substance abuse problem.” he says. “Somebody that has a habit would maybe buy an ounce, sell off eight or ten grams, and have enough for a week.” But twenty-one pounds? “We’re not talking a little nose candy here,” he says.

One of the criteria used in federal sentencing guidelines is the quantity of drugs involved. Because of the huge amount of cocaine he was caught with, among other things, Wilson could end up spending twenty years to life in federal prison and paying a $4 million fine. That thought makes Fred Davis crazy. “Mike was so impaired mentally and physically it wouldn’t have mattered if they had brought a dump truck load or just a little,” Davis says, “It’s strange to me that the government can decide how much cocaine they want to bring to the scene of the crime and determine what the sentence is.”

Some are not so sympathetic to Mike’s situation. They point out that when lawyers go down, they can take a lot of people with them.

Attorney Robert Rose represents one of Mike’s former clients, Joey Yocum, a Dallas man charged with conspiracy to distribute the drug Ecstasy. Yocum paid $25,000 to Mike, who told him he should plead guilty because he was sure to get probation. “Mike told him he was going to call in a ’gold marker,’” Rose says. So Yocum didn’t worry too much when Mike missed numerous court dates. When the sentencing date arrived, Yocum showed up in a black leather jacket, convinced he was going home. But to Yocum’s shock, the judge sentenced him to twenty years. He was taken away 10 prison. Rose is now trying to get Yocum a new trial.

“I feel bad for Mike,” Rose says, “lbut Mike’s drug problems led to the downfall of my client. He let cocaine rule his brain, and he left a lot of people holding the bag.”