UNTIL MOMENTS BEFORE THE MEETING THAT SATURDAY MORNING IN OCTOBER, Larry Littleton had no inkling what would happen. As chairman of the 120-man deacon body, he was lay leader of Prestonwood Baptist Church, and at the moment of its greatest crisis, he was out of the loop. Littleton knew only that as of midnight Friday, no decision had been made-though to him and many others, the situation seemed to have only one solution. As the deacons filed in, the tension in the room mounted to an almost unbearable level. Would the rumors be confirmed? What would happen to the church they had struggled for a decade to build, to the man they had followed with a passion that for some bordered on worship?

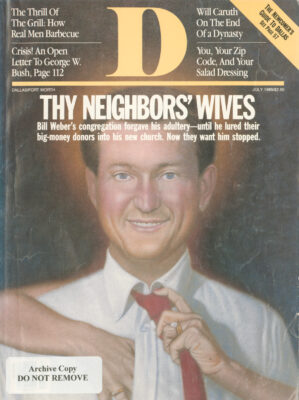

When pastor Bill Weber arrived, he told Littleton of his decision, then faced the men who had been the backbone of one of the fastest-growing churches in the Southern Baptist Convention, the North Dallas phenomenon that cemented Weber’s reputation, at forty-five, as one of the brightest stars in the Baptist firmament. This powerful preacher and these men had toiled to take the church from a handful of members in 1977 to more than 11,000. Now, they would learn, he had betrayed them.

With Jimmy Swaggart tears streaming down his face, the man who rarely showed emotion announced that he was “stepping down” from the pulpit, confessing that he had committed “personal improprieties.” Through the tears, Weber quoted from Psalm 51, King David’s pleading to God for pardon after his adultery with Bathsheba was unmasked. Woe is me. God forgive me.

Stunned, shocked, disbelieving, the deacons too began weeping. The rumors were true. Though he never said so, they realized that Weber had had an affair with a married woman, a beautiful, leggy blonde who was active in the church. The man who had helped so many of them through struggles now was brought down by his own. “It was a horrible, horrible experience,” says one longtime deacon. They’d watched from a distance as, one by one, Swaggart, Bakker, Railey had fallen from grace. Now, the humiliation was theirs.

In a weird way, Weber seemed relieved. He told the deacons he felt like he was on a race track, going around and around. If he could start just one more Bible study, visit one more sick person, he could rid himself of the guilt. He seemed to be saying he was glad to be rid of it all-the three sermons on Sunday, the Bible studies, the prayer meetings, the funerals, the constant, draining demands of a huge church. Maybe the stress they all had put on him was ultimately too much. Poor Billy.

Many, in the midst of their anguish, felt they should forgive him and take him back. After all, Christianity is all about forgiveness. Anyone could make a mistake, and he certainly seemed repentant. Besides, the rumor was that the woman had seduced him. What red-blooded man, even a preacher, could have resisted?

But many later came to feel that Weber’s prodigious tears were of the crocodile variety. “I think he thought he had lost, for the moment,” says a deacon who was at one point a staunch Billy backer. “He was sorry-sorry he got caught.”

Some of those close to him say that in the following months, they saw no real repentance or change in his life. Weber even began maneuvering behind the scenes to regain his pulpit. Mary Kay Ash, a longtime supporter, wrote a letter to the deacons saying that if Weber was not brought back, she would withdraw her financial support of the church.

When that foiled, he began scheming to start his own church, siphoning offboth the rank-and-file and some of the wealthy backers he had attracted to Prestonwood-all the while telling those around him that he was not starting a church.

So much for the poor-Billy theory. He couldn’t wait to get back on the merry-go-round.

But that wasn’t the only deception. As information oozed out over the next few months, the congregation discovered what only a handful of church leaders knew: instead of one affair, there were two. In 1985, Weber had been confronted by two deacons who had been given evidence gathered by a private detective indicating that Weber was having an affair with a young woman in the church. The deacons kept the incident quiet because Weber seemed remorseful, promising it would never happen again.

But it did. And, had they known Weber as well as they thought, they might not have been surprised. In fact, unknown to the deacons, a Southern Baptist preacher had confronted Weber about an affair as early as 1982. After Weber’s resignation, church leaders began to compare rumors and notes, approaching women privately to find out if they had been involved with Weber. Several confessed that they had, confirming what some leaders had suspected: that Weber had a pattern of infidelity. They say that during his Prestonwood years, he had as many as ten affairs, sometimes with several women simultaneously.

And contrary to the way he has represented the affairs to his supporters-claiming that he was seduced, and that the affairs lasted only a short time-Weber apparently was the aggressor. He picked out women in the church who were very attractive (and almost always blonde) and offered to counsel them or gave them tasks to do in the church. He spent time discovering their personal problems, and then used those against them. And he wrapped their relationship in a cloak of spirituality, convincing each she was special, different, one of the few who could help him serve God.

“Bill Weber came on to me sexually early in our acquaintance,” says one woman who gave a written statement to D on the condition that her name not be used. “I, at first, thought he was just a flirt. While all the flirting was going on he discovered vulnerable points in my life.

“He is very deceptive and seductive. I believe it is his ability to use words that makes him so believable. But he also had a spooky ability to get whatever he wanted. . .by using statements and persuasion that make you feel so needed. He always appealed to the side of me that wants to be somebody. He said he could give me an opportunity; he could fix me up in places where I could serve God. As the seduction grew more intense-phone calls, pleas for my help, pleas for secret meetings-I was willing along with him to take chances. I wanted to be with him at all costs.”

Once hooked, the women say, it was almost impossible to get away from Weber.

“He was relentless in his pursuit,” another woman told a church leader. Weber called her at home several times a day. The affair lasted twelve or thirteen months. When she tried to break it off, Weber wouldn’t let her. She and her husband finally left the church.

“Personally, I really felt played for a fool,” says a longtime church leader. “He literally raped the church,” says another.

The pattern of adultery points to a man who came to believe that the rules no longer applied to him, that what he was preaching on Sunday was meant for those in the pews, not the man in the pulpit. With the benefit of hindsight, some church leaders are beginning to see how they were used. Answerable to no one, Weber built a world of wealth and power where he hobnobbed with celebrities like Mavericks owner Don Carter, and prayed at Mary Kay Ash’s cosmetics conventions. He lived in an $850,000 house, drove expensive cars, had a church-provided country club membership, and (a fact unknown to parishioners) was making about $225,000 per year. He led the life of a corporate prince, and saw multiple lovers as his just reward.

While these former loyalists acknowledge that Weber helped many people by leading them to Christ, they are beginning to believe that he is dangerous. They fear that he has not changed, that he will set up shop again, and the same pattern will repeat itself, to the ruin of other women and the grief of other followers. You hear them hesitantly use the word “sociopath’-the clinical description of a likable, charming person who uses others to his own ends, compulsively lying, cheating, whatever it takes to get what he wants.

“This is not a sex scandal,” says one frustrated church member. “He’s sick. He’s a master of manipulation and deception. Bill’s got to be stopped, for the kingdom’s sake.”

But that person says it’s unlikely that anything can derail Weber. In May, at a Bible study the Webers started at Richardson Civic Center, a pink-clad Mary Kay Ash announced: “This is my church now.” After Weber explained that all their donations were tax-deductible, Ash urged the 300-plus in attendance to get out their checkbooks, explaining that last night she had given her contribution “from the bottom of my heart.” As others pulled out their checkbooks, she concluded: “Let’s get this thing on the road.”

THE GUIDED TOUR THROUGH THE HALLS AND OFFICES OF PRES-tonwood Baptist on a Sunday morning a year ago left me amazed, The building was more like an office complex than a church, with an atrium fountain cascading in the lobby. It seemed youthful, exuberant. The median age was thirty-five. Children swarmed everywhere; 2,500 kids attend Sunday school each week.

I had come in the spring of 1988 to write a magazine story about an innovative young preacher named Bill Weber. His businesslike approach to church growth brought him many admirers and imitators, even as his “soft,” upbeat message brought him critics. Each year, Prestonwood sponsored a church-growth seminar that attracted more than 600 church leaders last year. One of Weber’s mentors, Paul Yonggi Cho of Korea, spoke at the 1988 seminar. Cho had built a church of about 500,000. Now that Prestonwood had met his original goal of 10,000 members, Weber was raising his sights: 50,000, 100,000. The sky was the limit.

He was using what he called the “trotline” concept: have as many hooks in the water as possible. Joggers came for the 10K runs, housewives for the wok cookery classes. Bible studies met everywhere from Bent Tree Country Club to Mexican food restaurants, anywhere he could find a space. Hook ’em, then reel ’em in for the main events-the Sunday morning worship services, where they could hear the gospel.

And it was working spectacularly. Each Sunday, an average of twenty-five people joined the church. They had run out of parking and Weber was looking for a tract farther north to build a religious complex that would perhaps include a school, a music conservatory, and a television production facility.

Most of those he attracted were non-Baptists. From the beginning, when Weber knocked on doors, inviting people to come to Prestonwood, they would ask, “What kind of church is it?” He’d respond: “What kind do you want it to be?”

If they said, “Well, I’m a Methodist,” Weber would tell them, “Well, there will be a lot of Methodists there.” Only if pressed would he admit that Prestonwood was Southern Baptist; he didn’t consider this deception, just good public relations. Weber didn’t preach much about sin; he talked about forgiveness, acceptance, self-esteem. He knew that Baptists had a negative reputation in many circles. They talked too much about what you can’t do instead of what you can.

I had to agree with that. I grew up attending Southern Baptist churches. In addition to the Big Ten, there were other commandments to follow. Dancing was a sin, drinking was a sin, smoking was a sin, and so were a lot of other things that if you had to ask, well, better consider it off-limits.

As a teenager. I found a lot of joy in my faith. There were many adults at my church who seemed to be living the way they were telling us teenagers to live. But over the years, as I went through high school, I began to have my doubts. I saw my pastor flirting with ladies in the church-and them eating it up. I heard about the deacon who beat his wife. The unmarried soprano in the choir who had an abortion. The pastor and his wife moved away and divorced.

I was furious; all this talk about living for Christ was a lot of hooey. If the preacher, the deacon, and the soprano couldn’t do it, how could they possibly expect me to?

It was years before I came back to my faith, and it wasn’t in a Southern Baptist church. But I have no animosity against Baptists. The truth is that hypocrisy seems to be distributed fairly evenly across the band-from atheists to Episcopalians to Hare Krishnas. The point for me, finally, was you can’t put your faith in an earthly person.

But human beings tend to do just that. Weber built an organization that by its very structure assured that he would be the star, he would be the one in control, he would be the one they looked to for answers. And when he sinned, few would be willing to take a stand, to risk the collapse of mighty Prestonwood Baptist.

I didn’t see that a year ago. I saw another charismatic pastor, a strong, creative leader who was preaching an encouraging message. Angular, with arresting blue eyes and a powerful personal presence that one of his friends calls “a glow,” he walked with a confidence peculiar to the successful.

In a series of interviews, he seemed to be sincere. But there was definitely a dark side, something I couldn’t pin down. I thought it was the money. I quizzed Weber about his lavish lifestyle, about the scandals plaguing the world of religion. Did he think he was susceptible?

“I like the lifestyle we lead very much,” Weber said. “People may analyze me and say I’ve really succumbed. But if I thought I had, I think I’d get out. I’d have such a low sense of self-worth.” He talked about surrounding himself with people he could trust to tell him when he was wrong.

Almost four months after the story was published, I got a call from another reporter. The word was that Bill Weber was resigning; he’d had an affair with a married woman in the congregation. With sadness, then exasperation, I read Weber’s statements to the press.

Maybe it happened, he said, “because I am just a man who allowed himself to become physically exhausted and therefore spiritually exhausted. Maybe Satan targeted me at a time when our church was moving even more aggressively to find those who were lost and bring them into the family of faith and hope… A person’s strength often becomes a weakness in that the more sensitive you become, the more vulnerable you are.”

In all his statements, he managed to sound like “poor, pitiful me.” He never said a word about adultery; apparently his only offenses were that he was too sensitive, too effective on God’s behalf, and too ambitious for his church.

If I could understand that someone would want to put the best face on his public humiliation. I still didn’t understand the big question: why did he do it in the first place? He had to know that financial impropriety might be excused, but having sex with parishioners is the kiss of death for a Baptist minister. What could possibly make a man on top of the mountain, a man who seemingly had everything- wealth, professional respect, a beautiful wife-risk it all? And, having succumbed to the temptations of the flesh, would he be getting out of the ministry, as he had told me he would if he succumbed to the temptations of wealth?

I began asking around, trying to find out why someone like Bill Weber would self-destruct so spectacularly. Weber agreed to an interview, then canceled. Most church leaders refused to talk to me. Many who at first agreed would later call and cancel. Those who finally acquiesced did so reluctantly, even fearfully, often saying, “I don’t want to hurt the church”-“his family”-“the cause of Christ.” Almost all of them demanded in advance that I not use their names or any identifying descriptions. They were agreeing only, they said, to warn those people still following him who might not know the whole truth.

But when they began talking, the stories tumbled out. Many spoke of their love for Weber, how much he had helped them, how much he did for God. Then, in the next breath: how he used them, how he hurt people.

It was as if they, too, needed to find some answers, to understand the maelstrom that had swirled about them. They’re not the only ones. “We at the seminary ponder the ’Pres-tonwood paradigm,’” says C.W. Brister, professor of pastoral counseling at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Weber’s alma mater. How could an enormously successful leader, he asks, get involved in such paradoxical behavior?

Those who were close to Weber paint a picture of a highly gifted but desperately insecure man, driven to please his father, obsessed with acquiring wealth, power, and status, a man with little regard for the feelings of others, willing to do whatever it would take to build his empire. And it wasn’t enough to have wealth; he had to have the other status symbols too: most of the women were blondes, all “racehorses,” the epitome of the sexy North Dallas woman.

When the destructive behavior first began is unclear, “Somewhere along the line he lost sight of where that power, that innovation, that skill, that charisma came from- God,” says a woman who belongs to the church.

Brister describes a phenomenon known as the “rapture of the deep,” a feeling of euphoria experienced by deep-sea divers who inhale too much nitrogen. The initial intoxicating effect masks the fact that their minds cannot think or react clearly. In the disorienting “rapture,” divers have been known to pull off their life-giving air supply, or swim the wrong way, toward a beautiful underwater mirage that is certain death.

“People can slip over the boundaries, become a law unto themselves,” Brister says. “They get so involved in administration, their ambition, in the program, that they lose their bearings.” Weber, it seems, swam toward the mirage.

THE WEBER STORY DOESN’T START with Bill, but with his father, Jaroy Weber Sr., who began preaching at an early age, attended seminary, and became a Baptist minister.

From the beginning, Jaroy, a gifted speaker, was different from most other ministers. He wasn’t content with the meager salary earned by preachers. Why should ministers live like poor relations? In Mobile he began acquiring real estate, investing money from family and friends.

Jaroy’s last church was First Baptist in Lubbock, where he reached the pinnacle of his success. A dark-horse nominee, in 1975 he was elected president of the Southern Baptist Convention, a coalition of 37,567 churches.

The elder Weber raised three children- Jaroy Jr., Bill, and Nettie. Friends say that Bill was anxious to please his father and fiercely competitive with his brilliant older brother, who initially planned to become a missionary doctor. When he was fourteen, Bill walked down the aisle of his father’s church and told the congregation he felt called to preach.

“He was the middle child of three, with a lisp,” says a man who knew Weber at his first Dallas church. “The oldest son was the favorite, and was kind of a prodigal.” He is now a plastic surgeon in Los Angeles.

But Bill was ordained and began preaching at the age when other boys were still playing Little League. He went from a strict upbringing to abrupt freedom. “He essentially was turned loose at puberty,11 says a friend. “He was a preacher; they couldn’t very well tell him what to do.”

At seventeen, Bill attended Baylor University, where he met Robin Middleton, a striking, dark-haired, green-eyed speech therapy student who won all the campus beauty awards. They married in 1964 and later adopted four children. In addition to Robin’s beauty, Weber saw in her a personality suited to the life of a pastor’s wife. “I sensed an unselfish spirit,” Weber told me. “She’s not possessive. In this kind of work, you have to have a trusting mate.”

A teenager in the odd position of providing spiritual guidance to adults, Weber developed a stirring, motivational style of preaching, concentrating on upbeat messages that rarely spoke of sin. He frequently used himself in sermons. “He had an absolute skill about making himself vulnerable, showing that he was one of us,” says one woman. “He’d talk about getting caught speeding, for example. He would carry his crowd along with him.”

After Baylor, Weber entered Southwestern Theological Seminary, pastoring a church in nearby Alvarado. He arrived in a big blue Cadillac, almost certainly the only seminary student with such wheels. But his father had set a precedent. Why should a pastor have something second-rate?

Weber seemed to have the Midas touch with each congregation he served, After graduating from seminary with a master’s of divinity degree in 1967, he moved to the hundred-member Cedar Crest Baptist in South Oak Cliff. In three years, the membership had multiplied four-fold.

In 1970, Weber set his sights north of the Trinity River: Northway Baptist on Walnut Hill Lane. Northway’s membership, which was 350, had been eroding. Much of North Dallas was still flat farmland, but he could see something happening: a shopping center, an office building, a residential development would spring up overnight. Northway doubled, quadrupled. Weber began to wonder. Maybe this was the place for The Vision.

Several years earlier, Weber had met Robert Schuller, the California television preacher who created the Crystal Cathedral. In many ways, Schuller was to have an impact on Weber, who regarded television as a vital tool in spreading the gospel.

Schuller astonished Weber with a simple statement: “The greatest church in America has yet to be built.”

“I realized he was right,” Weber told me. No one in America had built a church the size of Cho’s in Korea. “If it ought to happen anywhere, it can happen here in Dallas,” Weber said. And he could be the one to do it.

But he had gone as far as he could go at Northway; the Vision was going to be something completely different. It would be everything North Dallas wanted and expected-the ultimate “cafeteria-style” ministry.

Weber and a few followers from Northway began to meet in homes for Bible studies in late 1976. Then they moved to the Fretz Park Recreation Center, but two years later, the membership was stagnated at 125. He was unable to decide whether to let go of the bird in the hand-Northway-or to grab the bird in the bush-the Vision.

A friend accused him of wanting to build Prestonwood because of the wealth that was obvious at every turn in the road-a charge that Weber denied. But in retrospect, it seems clear that North Dallas money was part of the appeal. Weber didn’t choose to chase his vision in another area where tithes on average household income would fall well below that of the city’s most affluent neighborhoods.

In February 1979, Weber resigned from Northway and became Prestonwood’s full-time minister. The building committee, headed by Mary Kay Ash, who followed him from Northway, raised money for the construction of what is now the Prestonwood fellowship hall. From the day they moved in with 700 members, Prestonwood was already too small.

People streamed to hear Weber’s messages. In Weber, many of the hurting, searching people in North Dallas found someone who soothed their pain and at the same time made their ambitions and frank materialism acceptable, even blessed. His sermons eventually caused some of the traditional Baptists who joined to leave, charging him with superficiality. There were always more to take their place.

But unknown even to those closest to him, Weber had a nasty secret.

Some say that the trouble began after his father’s death in 1985, when the “governor” was taken off his life. But there’s evidence that years earlier, Weber had started a series of secret sexual liaisons with women, usually members of his church. The rules he preached no longer applied to him. And though some got glimpses of the dark side of Weber, for the most part they shrugged it off. After all, how could something so good have a core so rotten?

The deacons might have gotten a clue when Weber, using church money, bought each a copy of a book he claimed had an enormous impact on his life: The Man Who Could Do No Wrong. The book, by minister Charles Blair of Denver, is a long exercise in explaining away Blair’s conviction on fraud charges. After being fined and given a probated sentence, Blair went on to bigger and better ministries. What was Weber saying? Unknown but to a few, Weber passed out the books shortly after being privately confronted by the two deacons who charged him with having an affair.

ALL BAPTIST CHURCHES ARE INDE-pendent, empowered to set up their own rules and regulations. Weber assured the deacon body that he wanted to be accountable to them, but whether by design or accident, the structure of Prestonwood Baptist in every way led to a situation in which he was accountable to no one.

The deacon body functioned as a service organization, not a decision-making group. Decisions were made in committees, which Weber controlled, then presented to the deacons for a rubber-stamp approval, And those chosen to serve as deacons and chairman of the deacon body often were people new to Christianity who had come out of troubled backgrounds. They looked to Weber as the great man of God who could do no wrong.

He had a different hold on his staff. A document later circulated at Prestonwood showed that five senior staff members were making $90,000 to $114,000 per year. The salaries bought a certain amount of loyalty.

Despite their loyalty, some of the staff members sensed that something was wrong. One wondered about the “unusually close” relationship Weber had with his female administrative assistant. And there was the nepotism. Weber’s mother had a paid job as head of the wedding committee and his sister worked in the television ministry.

Staffers wondered why, despite his success, he seemed to grow more insecure. They questioned his using “Dr.” in front of his name after receiving an honorary doctorate. They watched him manipulate others into saying what he really wanted to say. “He would never go to bat for himself,” says a staff member. “He always had someone else do it for him.”

And something else staffers couldn’t ignore: at times, Weber seemed truly paranoid. At one staff meeting, he looked around the room and announced, “Any number of you in this room could ruin me.” Bewildered, they looked at each other. What could he mean?

The biggest problem was the intimidation, the constant demands that seemed out of place in a church, where the primary goal was supposed to be helping others. At Pres-tonwood, the goal seemed to be bringing in members. “It was a pressure cooker,” says a staffer. “He was always on the offensive, always had to be in control. If we were not productive in our work, if we were not results-oriented, we’d lose our job. I felt like I had a foot on my throat.”

And to their further bewilderment, Weber seemed to be surrounded by an entourage of people whose sole purpose was to protect him from the staff and the congregation. Those who hoped to see Weber in his office had to run a gauntlet of a receptionist and two secretaries. He rarely consented to counsel or visit with ordinary, non-wealthy members. They were sent to the appropriate assistant pastor.

But those who could help Weber or the church got a great deal of attention. One wealthy couple says that they were disturbed because the day after they visited a Preston-wood service, they got three calls from the church staff, including one from Weber himself. Though they joined the church anyway, they suspected that if they were not well-to-do, he would not have called them. Once rich people were in, he went to great pains and expense to ensure that they were content. Though adapting a computer system donated by car dealer George Grubbs to the church system cost them more than $200,000, Weber demanded that the staff find a way to do it. “We are not going to offend George Grubbs,” he said.

But even the wealthy were not secure in their relationship with Weber. A developer named Russell Bones gave $1 million to the church; after he declared bankruptcy and moved away, Weber refused to return Bones’s phone calls.

The final straw for some came in 1987. Members Dick and Jinger Heath had taken their BeautiControl cosmetics company public. In gratitude to Weber, who had counseled them through marital difficulties, and as an inducement to Weber to stay at Prestonwood, the new multimillionaires donated $1 million to the church, designating that half be used to build a suitable home for Weber.

Weber went directly to the finance committee, and the slab was poured before the deacons were ever told about the house. He sold his own $350,000 home and banked the proceeds, taking out a mortgage to add to the donated funds. The result was an $850,000 home in an exclusive North Dallas neighborhood. The church owned a portion and Weber owned a portion; over a period of ten years, ownership of the house would be deeded to him until he owned it outright.

Whatever the reason, the timing was terrible. The Dallas economy was struggling, and it had hit his congregation hard. Several deacons resigned over the house deal. Others defended it, saying that Weber needed a suitable house in which to entertain. The new members’ fellowships had gotten so large, it was hard to hold them in Weber’s old home. But after the house was completed, the meetings were moved to the church fellowship hall.

IN LATE SEPTEMBER I988, PSYCHOTHERA-pist Dr. Les Carter began to hear rumors. The stories reminded the longtime Prestonwood deacon of something that had happened three years earlier, something he had hoped never to hear again. In 1985, he had been approached by family members of a young married woman who attended Prestonwood. A friend of the family had seen her riding in a car with a man who was not her husband and told them. Suspicious, they hired a private detective to follow her.

The detective took photographs showing her rendezvous with a well-dressed man about forty years old. She met him in a parking lot, then entered an apartment and emerged some time later. The family discovered the man was the woman’s pastor, Bill Weber.

Carter was an active deacon and former chairman of the deacon body. He contacted Phil Pierce, another deacon and one of Weber’s closest friends, Relying on a scripture that commands those who discover a believer in sin to “reprove him in private,” Pierce and Carter confronted Weber. To them, he admitted that he was having an affair, but said it had happened only a few times.

Weber seemed so filled with remorse, so chastened, that they kept the incident quiet. They attributed his sin to stress. They held many conversations with the pastor, advising him to cut back on his schedule, to spend more time with his family. And they encouraged him to get counseling. He never did. The woman did not leave the church.

In 1987 Weber’s secretary became suspicious of his attentions to various women. One day, she followed him, finding him with a female church member in a car in the parking lot behind a store on Campbell Road. The secretary confronted him, but Weber denied having an affair. She was moved out of the pastoral suite to the TV ministry and later quit the church, sharing her suspicions with several others.

In September 1988, when those rumors reached Carter’s ear, he asked for a meeting with Larry Littleton, chairman of the deacons, and Phil Pierce. Before Sunday morning service on September 25, the three confronted Weber, who admitted he had had another affair. Pierce wanted to handle it the way they had the first time, quietly. But the others knew it was beyond that; Littleton formed an ad hoc committee of six deacons to discuss what they should do.

Meanwhile, Weber preached three services that Sunday morning. That night, he was in no shape to preach. At the last minute, he asked youth minister Neal Jeffrey, who had no idea what was going on, to take over. As Jeffrey preached a hard-hitting message about the evils of sexual immorality, Weber sat in the congregation with his wife, who also had not been told.

Through the next two weeks, the tension built. The ad hoc committee met almost every day. They talked several times with Weber about what he had done and what he thought of his future with the church. Cruelly, Robin Weber was still kept in the dark; the Friday after the committee confronted her husband, she gave a talk to a group of women about having a healthy marriage.

On Wednesday night, October 5, the ad hoc committee met to take a vote. Pierce thought Weber should stay, and, unknown to the others, he had brought along three additional deacons who he thought would support his view. But five of the nine voted to recommend to Weber that he resign. “How could you do this to Billy?” Pierce asked the other deacons. “He’s been under pressure. He’s done so much for everyone. And everyone makes mistakes.”

Weber and his inner circle, which included Pierce and staff coordinator Curt Marshall, set up a command station in Weber’s study at home, trying to consider all the options. Weber didn’t want to resign. Perhaps a sabbatical or a short-term leave would be enough.

A meeting of the deacon body had been scheduled for Saturday morning. On Thursday, three top staff members visited Weber at his home. They told him that if he did not resign, they would have to quit. But on Friday, no decision had been reached.

That Saturday morning, on October 8, Weber announced that he was “stepping aside” because of “personal improprieties.” The church was never told outright that there had been one affair, much less two. But immediately Weber began to struggle to get back into the pulpit, letting it be known through his supporters that he was willing to return.

William Tolar, dean at Southwestern, was brought in as interim pastor. He says his job was to help the church heal. “People are shocked, stunned, embarrassed, hurt. Some are angry. They’re almost traumatized” Tolar says. Some were turned against each other. “Some felt their leaders knew about it earlier and didn’t tell them.”

Pierce and Carter came under criticism for not making the first incident of adultery public. Carter will say little about what happened. ’This whole incident has been extremely awkward for all of us who have been involved with it,” says Carter. “I wish it had never happened. It’s caused good friends to question each other’s motives. Bill Weber has done many fine things for the Lord’s work and the North Dallas community.”

But it was clear early on that most of the church leaders felt that Weber needed to get out of the ministry, at least for the foreseeable future. A minister can be forgiven, says Tolar, but he should not be put back in a position of leadership. “The Bible holds ministers to high standards,” Tolar says. “When leaders shatter confidence, they lose their capacity to be leaders. A bank president can be forgiven embezzlement, but you don’t put him back in charge of the vault.”

Weber set up a “watch-care” committee of three men who would meet with him weekly to provide support. “Billy of his own accord decided to put together a group of men to counsel and advise him,” says Charles Major, one of those chosen. “It was set up to talk about things happening in his life, how he’s relating to his family, and the direction his life is going.”

The church voted to provide Weber with a severance package that included $10,000 in counseling fees. The salary provision of the package brought on a huge battle. The personnel committee recommended giving him nine months’ salary and medical coverage, but in its presentation to the deacon body, Pierce pushed for a full year’s salary. Many deacons were incensed. Near midnight, after much heated discussion, a letter from Weber was presented saying that he did not want anything, that “he would trust God” for his needs.

“It was a ploy,” says one leader. “They had that letter all along.” After much infighting-with one faction trying to find out exactly how much Weber made, and the other refusing to reveal it-the church finally voted to give him two months’ salary, cover his car payments until December, and extend the time he could stay in the house until June 30. Then he would have to buy it from the church or move out, Weber began to tell astonished friends he was “bitter” toward the church because it forced him out and gave him only two months’ pay.

Weber began meeting weekly with the watch-care committee, which was using a book called Rebuilding Your Broken World as its guide. “I wish 1 had had this for a long time,” Weber told a reporter. “It has been an experience of genuine love. No matter what I do in the future, I will always have a group like this to meet with regularly.”

But according to others, Weber almost immediately began ignoring the book’s recommendations. It suggested serving others in a quiet capacity, perhaps in a prison or a church in a poor area. And it was adamant about not talking to the press or drawing attention to oneself. But Weber made no effort to get involved in a less glamorous ministry. He continued to talk to the press. He told one reporter that he was counseling with a group of pastors; he actually met with them once, didn’t like what they said, and never met with them again. In January, during a visit to Los Angeles, he preached in the church of a prominent black pastor named E.V. Hill.

And his attitude remained troublesome. He told friends that Jimmy Swaggart called to offer consolation-but he was contemptuous that the other defrocked preacher thought their sins were anything alike. Swaggart’s sin was dirty, Weber said. That woman was so ugly… It was as if his own sins were somehow in better taste. But he took to heart one thing Swaggart said: don’t wait too long before you get back in the pulpit.

Even before the end of the year, Wsber and his supporters were telling others that he was going to start a new church in Plano. He | wrote a letter to a pastor in Hot Springs, Arkansas, telling him that the new churcn would be “bigger and better” than ever. But he kept giving signals to others that he was not starting a church.

While the Prestonwood congregation was still in turmoil, with attendance and contributions down significantly, Weber’s supporters sent out 400 invitations to a “Sweetheart Party” on February 10 at Stonebriar Country Club. People suspected its true purpose was to announce Weber’s new church. On January 26, The Dallas Morning News said that Weber was considering starting a non-denominational church because “it appears there is no place for me in the Southern Bap-tisl Convention… I feel a greater call to ministry than ever.”

But something happened. It might have been an early February ski trip Weber took with fourteen other men, including Piano pastor and author Gene Getz, where he talked about his plans to start again. “He didn’t get an enthusiastic response,” says one deacon. Several hundred people showed up at the party, but no announcement was forthcoming. “It came off like a flat, stale social event.”

Meanwhile, church members and leaders had been comparing rumors and piecing together information. People began remembering incidents. The way Weber disappeared for hours at a time when a certain woman from Hawaii came to town. How one man discovered Weber at his home in the late morning, talking to his wife. Weber explained that he had driven his car down the alley and into the garage and closed the garage door because he didn’t want to make other church members jealous.

It was clear that there was more than he was telling them. “When he was asked [before his resignation] if there were any others,” says one deacon, “he said no. And there are.” Several church leaders have information that indicates Weber had perhaps as many as ten affairs over as many years, and that some of the affairs, far from being the short-term dalliances he described to a few deacons, were intense, long-term involvements.

“One beautiful woman was not enough,” says a deacon, referring to Weber’s wife. “He was set up as an ideal man. He was adored and he ate it up.”

But how he justified it to himself is a mystery to those around him.

“It happened probably through a series of rationalizations,” says William Tolar of Southwestern. “Sometimes we see this in the rising young stars. They feel they are the exceptions, that the rules don’t really apply to them. There’s a subtle, subtle type of rationalization that goes on. But for a minister to do it again and again, he’s developed a pattern of egotism. It boggles my mind.”

After the Sweetheart Party, Weber fell into a clinical depression. Thin, haggard, he began seeing a psychiatrist, who put him on medication. On Easier Sunday and for several Sundays thereafter, he and Robin attended Prestonwood’s Sunday morning service. After the service, an impromptu receiving line for the Webers formed on one side of the lobby, while Tolar received people on the other. “What bothers me is that this reopens old wounds and hurts,” says Tolar.

With the encouragement of the watch-care committee, the Webers started a small Bible study in their home. “We felt they needed an opportunity for Christian fellowship,” Major says.

They also began sending out flyers for $250 weekend seminars on “bipolar” communications, taught by Bill and Robin. After getting few takers, Weber announced, again in the press, a six-week Bible study to be held at Richardson Civic Center on Tuesday nights. The first class attracted 330 people, Mary Kay Ash included. In the fourth week, they moved to a room that would accommodate 1,000. When asked about Weber’s problems, one man at the Bible study replied, “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.”

On May 7, Weber stepped back into a Dallas pulpit for the first time, preaching at the predominantly black St. John Missionary Baptist in Oak Cliff. Part of his sermon stressed the importance of confessing secret sin to God. He reiterated his feeling that he was called by God to preach. “I said a long time ago that if I preached only what I could live up to, I wouldn’t preach a lot,” he said.

That worries those who feel that Bill Weber has shown only superficial remorse for his sins. They look back over the last six months and see, again, a pattern of manipulation and lying. “He’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” says one church leader. Several have become so bewildered by Weber’s behavior that they have begun reading about sociopaths. They look at the descriptions of sociopathic behavior and see the Weber they know: charming, likable, gets along with people well.

And selfish, with a need for control, and resistant to accountability. Seemingly deep but actually superficial. Prone to irresponsible behavior, particularly with money, alcohol, or sex. Narcissistic lifestyle, A very strict or very loose upbringing. Filled with unresolved anger. “He can go from a Swag-gart-like appearance to absolute calm in an instant,” says one deacon.

Though he wouldn’t comment about Weber directly, Dr. Louis McBurney, a Colorado psychiatrist, has counseled hundreds of pastors who have fallen from grace. By far, most of them are pastors who first become emotionally involved with a parishioner or who, in a period of doubt, met a woman who provided the affirmation they desperately needed. Very few, he says, have a pattern of infidelity.

“These guys don’t come into counseling or treatment very often,” McBurney says. “They have a good defense system.”

Like Weber, they are often effective in dealing with people, but have no strong conscience or guilt mechanism, he says. “They are unhappy if they get caught, but don’t see what they did was wrong. Usually they acknowledge only as much sin as they have to to move things along. They have a lot of underlying hostility. They want power and control over women. They often are acting out the need to work through early life feelings about masculinity.”

McBurney says that even people who know what Weber did will still be attracted to him. ’”They are powerful men,” he says.

Prestonwood Baptist is moving on. On May 7, while Weber was preaching in Oak Cliff, the church he built was listening to their new leader, chosen by a committee after a six-month search: thirty-eight-year-old Jack Graham, a conservative minister from West Palm Beach. That evening, 99.3 percent of the congregation voted to approve his appointment.

Weber is negotiating to buy his expensive home at a deep discount. He tells those who come to his Bible study that the past seven months have been “trying, but enjoyable.”

“A truly happy man is one who can enjoy the scenery on a detour.” he says, as if the trials of the last few months were nothing more than a small setback. He says that his marriage is “better than ever.” He talks about a new commitment to “openness and honesty” in their relationship, about his willingness to be accountable.

But others say Robin Weber still doesn’t know the whole truth. And in late spring, the watch-care committee was suspended.

Bill Weber, it seems, is ready to start again.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte