ON A BLEACHED WHITE morning in late August, four months after his wife was strangled into a coma, the Rev. Walker Railey agreed to see me at his home on Trailhill Drive. Railey hadn’t lived there since that April evening when he hadfound his wife,Peggy,crumpled on the floor of the garage. Her faceand neck were covered with dark blue splotches; a thin wire, apparently from a weed trimming machine, had been wrapped tightly about her neck. Railey would tell me later that it took him three months from the night of Peggy’s attack before he could stand to come back to the place where the crime occurred, his familiar Lake Highlands residence, with the pool and gas grill in the back. He had come then to straighten the place up-the house had been put up for sale- and he said one of the first things he noticed was the Sunday newspaper television section opened to Tuesday, April 21, the infamous night when the city’s most extraordinary crime story since the Kennedy assassination began to unfold. John Yarrington, the choir director at First United Methodist Church and one of Railey’s closest friends, was there that day when Walker Railey saw the television guide open on a table. Railey stopped and stared at the date that has locked his life in a freeze frame. “Life in this house,” John Yarrington softly said to the minister, “stopped for you on April 21.”

WHEN 1 MADE THE AP-pointment to see Railey, he was renting a small apartment at an undisclosed location in Dallas, rarely venturing out. He was living like some deposed Third World leader, not sure where his exile might take him next. But he agreed to talk to me at the home on Trailhill Drive. “I’ll park in the back,” he said. “When you drive up, wait for me to come outside and get you. If the neighbors see you go in and don’t know I’m there, they might call the police.”

We sat at the kitchen table, sipping coffee. He was wearing a short-sleeved white Mexican wedding shirt and khaki slacks. His wife was 100 miles away, lying in a coma in a nursing home, but her presence dominated every square foot of the house. Her apron was hanging next to the refrigerator. A little family of ceramic ducks was perched on top of a cabinet. This looked like the home of a close-knit family. From the kitchen, I could look across into the bedroom of Megan, the two-year-old. Her stuffed animals were still on the bed. Railey said that after the murder attempt on his wife, “I received a stack of letters from all over the country, and most of them said essentially the same thing-that my strength and faith would see me through this tragedy.”

Railey stared at me. “But I knew it wasn’t true. I wasn’t strong. I felt scared to death.”

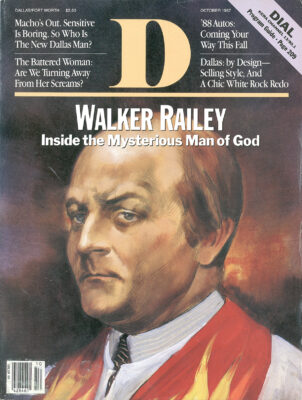

That fear would lead to his failed suicide attempt, and soon to allegations that it was he who tried to kill his wife. Suddenly, Railev found himself the center of a story that was powered by all the engines of epic drama, a saga of passion, romance, violence, and sin. As one shocking secret unfolded after another, the image of Walker Railey began to carry a slight reverberation of the old myth of the fell from paradise, for here was a man whose life seemed destined to tell one story, and ended up telling a much different tale instead. Each Sunday morning, thousands came to First United Methodist to sit spellbound as Railey, perhaps Dallas’s finest young minister, give shape to the dark and ambiguous heart of things that churned within everyone’s lives. As he pored over the Scriptures, he was like a poet, blessed with a riveting preaching style, a master at explaining the nature of right and wrong to his world of confused ordinary men and women. So how could it be that this man, as he would write in his suicide note, had “demons” within him?

In his old kitchen, filled with sunlight, Railey toyed with his coffee cup. Polite, thoughtful, his voice tinged with sadness, he began to discuss what had happened to his once-charmed career. He wouldn’t discuss any of the details of the murder investigation, but he was open about other things. He told me that his last paycheck from the church would arrive in four days and that he was worried about how he would now make a living. “Other than the note on my house and my car, I’ve never owed anybody anything for more than thirty days,” Railey said.

I asked him how he now spends his days. In the mornings, he said, he reads certain passages from the Bible and immerses himself in a personal devotion. Then he talks to his lawyer or calls his wife’s parents. They are still close friends, he says. Most days, he visits his two children, who live with choir director Yarrington. Sometimes, in the afternoon, he plays golf alone. Otherwise, he almost never goes out. He explained that he used to have two lives-a public life and a private one. “Now,” said Railey, “the two lives are a public life and a very public life”

He said, “People wonder what I do the rest of the time. Well, when I first got out of Timberlawn Hospital [after his suicide attempt], I usually spent the rest of the day crying.”

Sundays, once the focal point of his life, are now the most painful of times. “Well.” Railey said, “I still get up at 5 a.m. on Sundays and go through the same sort of routine I had while I was preaching.”

He paused. Then he said, “On the Fourth of July weekend, I worked up the courage, or was foolish enough-I’m not sure which-to watch the telecast of the services at First United Methodist. The mistake I made was watching the service alone,” I imagined the reverend bent forward, staring at the television, looking at the familiar sanctuary, the choir, his former associates in the pulpit, maybe shutting his eyes during the prayer. It was then, Railey said, that he was engulfed by the realization that he would never stand again in the pulpit where he had reigned for seven years,

“I was pretty overcome,” Railey said. His statement spoke for an entire city. Through the spring and summer, Dallas watched, horrified and bewildered, as the once-charmed career of this vibrant spiritual leader came to a shattering end. For many, the affair became more than a crime story. It was a bizarre study of what the Bible calls the dark night of the soul. What happened to Walker Railey? What made his career so great, so full of promise? And what led to his haunting, ambiguous downfall?

AS SOON AS THE NEWS LEAKED that police were considering Walker Railey a suspect in the strangulation of his wife, eager reporters began to sift through his past, looking for the one clue that could point, like a defective gene, to the source of Railey’s troubles. It became a sort of game, and the characterizations of the man were sometimes unfair. But invariably, the same word was used in the interviews to describe the pastor-ambitious. He was a workaholic, he hated to delegate authority. and he wanted to run everything himself. It is no secret that many church people feel uncomfortable with any minister who, in a profession that stresses humility and submission to God’s will, displays a strong drive to succeed. Still, with Walker Railey, even the most sympathetic parishioners sensed a determination in the young minister that they did not fully understand.

In many ways. Railey’s childhood was the perfect backdrop for a Christianized Horatio Alger story, of a boy who knew early what kind of work he would have to do to overcome the obstacles in his path. If a person is to start from humble origins, there is no better place than Railey’s hometown of Owensboro, Kentucky, gateway to the great American Rustbelt. A hardworking little town of 54,000 population, Owensboro, located on the bank of the Ohio River, has a couple of distilleries, a cigar factory, and a plant that manufactures Ragu spaghetti sauce. Most of the residents work in middle-class occupations.

Railey’s father, Chester, is a sheet-metal worker. He recalls that when Walker was a boy, the family was often “broker than the Ten Commandments,” yet still maintained something akin to a “Leave It to Beaver” lifestyle. “Financially,” says the elder Railey, “I couldn’t help Walker much. In high school, he had to take a job with the city, planting flowers in the park.”

In sermons and in conversation, however, Railey seldom referred nostalgically to his hometown. He has mentioned that his father had a drinking problem. In fact, the real satisfactions of Railey’s boyhood came in the form of schoolwork-and preaching.

The single most influential event of Railey’s youth, friends and relatives say, came in his junior year of high school, when he asked his mother to ask the neighborhood minister if he could deliver a sermon, “He wrote it himself,” says Chester Railey. “About 350 people were there, mostly his friends and classmates.” The topic was prayer, but what people remember was his ease and persuasiveness in the pulpit. Whether Walker knew it then or not, preaching was going to be his ticket out of Owensboro.

He went off to college at Western Kentucky University in nearby Bowling Green, supporting himself for a while as a clerk in a furniture store. Later he transferred to Vanderbilt University, 130 miles from Owensboro. Railey was thoughtful, hardworking, certainly blessed with intellectual prowess. As Chester Railey puts it, “Walker was always determined to be the best that he could be.”

There was no question about Railey’s devotion to the church. Under the dark cloud of the Peggy Railey case, it has been easy to forget how dedicated Railey was to his calling. After Vanderbilt, he came in 1970 to SMU’s Perkins Theological Seminary, where his gifts were instantly recognized. One seminary professor said Railey was the best preaching student he had ever taught. Others from that era recall the envy they felt when they watched Railey perform in class.

Perkins is far from an emotional, Bible-thumping Christian retreat center. It is fiercely academic; professors stress complex theological thinking. If a student is going to profess a belief, he or she had better be able to defend it with something other than a vague profession of faith. It was there that Walker Railey developed one of the most forceful, appealing preaching styles ever seen in the Methodist Church.

Perkins was also where Railey met Peggy Nicolai, who had come there from Milwaukee to get a graduate degree in sacred organ music. Although she was never a dynamic, outgoing type like Railey, her soft, loving manner was considered the perfect complement to her husband. Obviously, any church committee looking for a new young pastor would consider Walker and Peggy Railey as ideal-he was the powerful young minister, and she was his sweet wife. He would preach, and she would play the organ, He would work late, and she would stay home to take care of the two children.

In 1973, Railey was given his first assignment, as associate minister at First United Methodist Church. He served there for three years before moving on for a four-year stint at Christ Methodist Church in Farmers Branch. In 1980, he was brought back to First United as senior minister. For a young seminary student to jump so quickly into the game at these large churches was extraordinary; usually, new ministers out of Perkins are sent to rural parishes for seasoning. But the Methodist hierarchy knew Railey was a different entity. In his sermons, he never rantedor wore himself out slamming Satan to the ground, but his words had a bold, graceful beauty, delivered in a voice that still held the twanging chords of his Kentucky youth. Railey’s movements conveyed a tremendous energy, the sort of driving power that campaigning politicians try to effect when they roll up their sleeves and walk through farm lands in Iowa. When you looked at the Rev. Walker Railey. you remembered him.

Always, Peggy acted as Walker’s contented shadow, but the truth was that she was under tremendous pressure herself. And only a few parishioners could comprehend it. A minister’s wife is often judged more harshly than the minister. She must have the pleasant smile, the reassuring comment, and she must never skip over talking to anyone at a church dinner. A minister, of course, can: be temperamental, roaring like a lion for God. But the minister’s wife must never show a blemish. Peggy Was not always comfortable with that life. As a few church members quietly told reporters after the murder attempt, Peggy was not obsessed with at-tending every church function; occasionally, she failed to display the constant cheerfulness that some members seemed to demand of her. She had few close friends. Some, members did not understand why she in-stalled a second private telephone line at home and rarely gave out the number. Churches are like small towns when it comes to word getting around, and a minister and his wife quickly learn that they are always on | display, always talked about. There is little privacy, and though Walker might have liked the attention, thrived on it, Peggy certainly didn’t. She was more than an ornament, an adjunct to his ministry.

THE FIRST UNITED METHODIST Church is a handsome and distinguished structure of traditional design that sits in comfortable juxtaposition to the contempo-rary contours of the Dallas Museum of Art that faces it across Ross Avenue. There are few churches in Dallas as steeped in tradition as First United, a keystone in the Methodist movement in the Southwest for the last 140 years. The portraits of six previous senior ministers hang in the foyer of the building; all of those men later became Methodist bishops, the equivalent of a cardinal in the Catholic Church.

And the senior ministers of First United , Methodist were always old and wise. The youngest one ever appointed to that position was in his fifties-until Walker Railey. In ’ 1980, Railey, then just thirty-three years old, ] was named by the Methodist leadership to head the church. His appointment practically guaranteed that he would someday ascend to the post of bishop.

Railey was young, but if there were any questions as to his ability to lead, they were quickly stilled as the young man took the old church, its membership slowly dying off as in most downtown churches, and reinvigorated it with his unique, forceful presence. Under his rule, the congregation steadily added numbers, building an annual operating budget in excess of] $2 million. He attracted a flood of younger people, upscale North Dallas yuppies who looked like the types one saw in various luxury advertisements, those who knew how to buy the right car land the finest kind of clothes.

No church leader seemed luckier. First United sits in the middle of Dallas’s Arts District, the city’s new symbol of a chic, cosmopolitan culture, and it was led by a man who many thought was unparalleled in his ability to dramatize the fullness of the Christian life. The eloquent Railey would stand in the pulpit and kick his people right in the heart, denouncing society’s lust for the almighty buck. Gesturing toward the museum, he’d dryly remind them that in status-happy Dallas, it is the people who buy the art, not the ones who make it, who really count. The reverend also twisted the knife when it came to one of his fundamental messages: that racism constitutes the foundation of American conservatism.

“Sometimes we become so distracted by this beautiful skyline in downtown,” Railey said in one Sunday sermon, “that we think every edifice in Dallas glitters. But right in the central core of this city, not to mention all around it, there are shacks ready to fall down within which live people who can barely stand up. Like the English pauper, these helpless individuals could easily say, ’What good is it to be a citizen of a country where the sun never sets if you have to live in the gutter where the sun never rises?’ People do not see anything wrong with that. That is the problem. People just do not see.”

But Railey also knew how to make his church members laugh and feel like a community of believers. He said in a sermon last spring, “Early last week, I answered my telephone in the office and heard a voice on the other end say emphatically, “For God’s sake, reverend, why can’t you do something about that dreadful cross out in front of your church?’ It was a woman who had visited the Dallas Museum of Art across the street and was bothered by the contrast of the loveliness of the culture over there and the ugliness of the cross over here.

“At first I thought of reminding her that three years ago the museum had a huge sculpture in front of the building that was named ’The Gates of Hell.’ If they can have The Gates of Hell’ over there, why can’t we have ’The Old Rugged Cross’ over here?”

On such occasions, the audience roared. They loved him. He seemed to be speaking to each of them individually,

Apparently, Railey was as effective in the behind-the-scenes political machinations of the Methodist hierarchy as he was up in the pulpit. He seemed to be everywhere at once. President of the Greater Dallas Community of Churches. Chairman of the Board of Ordained Ministry. Author of several books. He gave speeches constantly. In 1986, he’d contracted to preach sermons on the nationally syndicated “American Protestant Hour,” a radio broadcast carried in several hundred American markets.

Indeed, he did know how to get ahead. People speak of his ambition, his large ego, but the word “patient” is rarely used to describe him. A Catholic priest recalls driving with Railey to an interfaith gathering in Dallas. “There was a traffic jam on the freeway and suddenly Walker veered off the road and drove up an embankment looking for a shortcut,” the priest says. “Then he got lost roaring up and down the side streets. I remember thinking, ’I’m going to have to pray for this young man.’”

Evidently, some of the senior clerical figures throughout the Texas United Methodist framework felt that Railey had also jumped the curb a couple of times with an ambitious plan to be named bishop in 1988.

The talk of Railey’s driving ambition began as far back as 1980. Railey was barely installed in his lofty perch as the young senior minister at First United in Dallas when suddenly he was on board the private jet of Houston oil man Eddie Scurlock, flying to Houston at the behest of the late Bishop Finis A. Crutchfield. Railey, it developed, had been handpicked by Crutchfield to take command at St. Luke’s United Methodist in Houston.

“Crutchfield was a tame duck bishop and had stayed an extra month or so specifically so that he could appoint Railey at St. Luke’s,” says Louis Moore, who was religion editor of the Houston Chronicle at the time. “But something went awry and the next week, Railey was back in the pulpit in Dallas telling his congregation that he’d turned down the position at St. Luke’s.

“Well, a young minister doesn’t ’turn down’ the wishes of the bishop,” says Moore, “and I remember that Crutchfield really became indignant about that kind of impertinence. Crutchfield then came forward and said that he’d never offered the job to Railey to begin with. That whole episode created quite a flap.”

At some point, Railey mended his fences with Crutchfield, who died last May, and continued on the course he had charted to become bishop himself. This might have taken place as early as July 1988, when the South Central Jurisdictional Conference will convene to elect a bishop.

“Railey might have still been regarded as loo young in 1988,” says Moore. “But he was in beautiful shape for ’92.”

There has been talk that Railey’s quest for the bishop’s post might have been a smokescreen for yet another ambition. Even as recently as this past March, Railey was privately seeking to become pastor of The Riverside Church in New York City, one of the premiere Protestant pulpits in the country. Riverside’s present minister, William Sloane Coffin, gained fame with his work in the civil rights and Vietnam protest movements. But Coffin had developed a rocky relationship with the church board, and Railey was reportedly hoping to be next in line for Coffin’s job. When he learned last March that he did not get the job-Coffin mended his fences with the church board- Railey was deeply disappointed, says one Dallas minister.

So Railey was a rising star in the Methodist Church-the object of adoration from his flock, envy from some Methodist ministers who had been preaching since before Railey was bom. Then, during this past season of Lent, the time leading up to Holy Week, Walker Railey’s life veered in a direction no one had foreseen.

SOMETHING PECULIAR HAPPENED in Dallas on March 29, twenty-three days before Peggy Railey was attacked. After a balmy winter when the wildflowers appeared about a month early, the city was blanketed by a freak snowstorm. It was about that time of year that a handful of the First United Methodist faithful began to sense that there was something out of whack with the Rev. Walker Railey as well. The more observant regulars in the congregation felt that some of the customary power of his sermons was missing. Some of his admirers noticed that he seemed troubled.

One of Railey’s constant themes was the indifference of the white middle class to the continuing problems of blacks and other minorities. In his Martin Luther King Day sermon, Railey decried a recent Ku Klux Klan march in Georgia and reported rumors that the Klan sponsored a training camp somewhere between Dallas and Fort Worth.

Railey insisted that, “There is more racial tension and polarization in Dallas, Texas, than many fine, upstanding citizens are willing to admit. It will not get any better until we see it and do something about it.”

Then, some weeks later, the news broke of the threats on Railey’s life. Apparently written by a white supremacist, the letters warned Railey to stop preaching about racial injustice. It was a bizarre episode. Why would someone threaten Railey? Surely, there were other, more prominent figures in other parts of the country who were delivering much stronger messages. Railey was just one minister in one church, in a town never known for overt racial strife.

Nevertheless, the reverend turned the letters over to the Dallas police, who took them seriously enough to forward them to the local FBI office. The Rev. Bill Bryan, pastor of the Grace United Methodist Church and a friend of Railey’s, says he learned about the threats through First United Methodist executive minister Gordon Casad. “At first, they didn’t seem real alarming,” Bryan says. ’’Ministers occasionally have to deal with unpleasant situations. A fellow who lives near my church was angry about some problem not long ago and it reached the point where I said, ’Come on. You wanna take a swing at a Methodist preacher?’

“But when the letters take on a pattern, like the ones Walker was receiving, then it gets kind of frightening.”

Railey, however, was not the only person in his family receiving threats. Peggy Jones, a real estate broker who negotiated the purchase of the Railey’s house on Trailhill Drive a year and a half ago, says that Peggy Railey had been coping with some anonymous unpleasantness of her own.

“She had been receiving phone calls for the better part of the previous year from a woman-threatening, very ugly, nasty calls,” Jones says. “It reached the point where Peggy put their public line phone on a permanent answering machine and had a private line installed and gave that number only to a select few people. That’s the primary reason why Peggy wanted to buy the new home, because she wahted a place where she might feel a little mote secure.”

The home the Rajleys eventually purchased, previously owned by SMU basketball coach Dave Blissi was equipped with a formidable security alarm system. Yet despite the precautions, as Easter approached, the tensions that seemed to be gripping the Rev. Railey appeared to intensify.

“It was whispered around the church that he seemed like he was on the brink of a nervous breakdown,” says one church member, “but most people felt that might be due to his incredible work load.” Another minister says that Railey “kind of snapped” when he learned that he hadn’t gotten the job at New York’s Riverside Church.

Railey seemed to take the death threats seriously. When he delivered his Easter sermon, he stood in the pulpit wearing a bullet-proof vest. Two plainclothes policemen were stationed at the side exits of the sanctuary. Another letter, the sixth and the most ominous, had appeared at the Rev. Railey’s office that week. “Jesus may have risen on Easter,” the letter read, “but you’re going to take the fall.”

After the sermon, one of Railey’s closest friends visited the pastor in his office. He recalls that Railey demonstrated a “pretty pronounced feeling of anxiety. It was as if he was having difficulty maintaining control.”

And then, in the early hours of April 22, three days after the Easter sermon, Railey appeared on the steps of a neighbor’s house and said, “Call the police. Something has happened to Peggy.”

ON WEDNESDAY MORNING, APRIL 22, A group of twelve Methodist ministers met for their weekly ritual: a 7:30 breakfast at the University Park United Methodist Church, followed by an exchange of book reviews. Walker Railey had been a regular in the group until he couldn’t spare the time any longer. But Gordon Casad, his associate, was usually there.

Casad was late showing up that morning, and when he did, he looked absolutely gray, Bill Bryan recalls. Then he broke the stunning news: Peggy Railey had been strangled and was in a coma at the hospital.

Bryan says, “I drove away with a feeling of horror and disbelief. At first, I felt frightened for my own family. We’re in the same neighborhood. Walker and Peggy had been by the house recently for a dinner party. You read the papers and think, ’This happens a lot,’ but when it happens to someone you know and love…” Bryan’s voice trails away.

The public read about it the next day. The shattering narrative of the newspaper accounts said that Railey, after working until midnight at the Bridwell Theological library on the SMU campus, returned home and found Peggy unconscious in the garage of their home. She was rushed to Presbyterian Hospital, where tests quickly revealed that Peggy was brain dead. Dallas police had stationed two uniformed police officers outside the door of her hospital room to guard against the ghoulish possibility that the assailant might attempt to slip back in and finish the job.

Though the papers continued to insist that Mrs. Railey was “choked,” the correct forensic term is “ligature strangulation.” Choking occurs when an object creates an obstruction to the air passage. But in Peggy Railey’s case, a linear object, a thin wire, was looped around her neck with enough pressure to shut off the oxygen supply to her brain.

Sometimes, after a blow to the head, a person might remain comatose for days and still recover. But the coma brought on by strangulation “creates dreadful chaos within the brain,” according to a pathologist at the UT Health Science Center. The irreversible situation is commonly known as “brain death.” “You can put them on a respirator, but they’ll never be a person again,” the pathologist says.

As reporters and members of the church began streaming into the hospital around sunrise, Railey cracked. His first concern, he said, was for his children, Ryan, five, and Megan, two. “I’ve got to see my babies,” he said, “I don’t know how they are going to take this.” And, in a trembling voice, the pastor told reporters, ’”Peggy was such a good mother to them.”

That statement, more than anything else, broke the collective heart of the city. Shocked and grieving over such a grotesque, baffling crime, few noticed that there were a couple of details about the crime that just didn’t make sense.

IN A GRIM LITTLE OFFICE BUILDING ON the fifth floor of the city’s Municipal Building, homicide investigator Lieutenant Ron Waldrop began to investigate the strangling of Peggy Railey. Right off, he knew the odds were against him in finding the culprit. Since Waldrop was promoted to murder investigator five years earlier, his department had accumulated a file of more than 500 murder and mysterious death cases that are still stamped “Unsolved.” In the case of Peggy Railey, there were no eyewitnesses and little physical evidence. A neighbor of Railey’s said that on the night of the crime, she saw a man running between two houses. But that was about it.

Still, as Waldrop pored over the Railey file, he became convinced that the person who entered the garage at 9328 Trailhill Drive and attacked the minister’s wife was no random intruder. There was no sign of forced entry; no indication of any struggle inside the house. A check with the burglary division had shown no recent pattern of break-ins in the Railey neighborhood.

The first thing Waldrop’s investigators had done on the night of the attack was conduct the standard house-to-house interviews with everyone on the block. No one had heard or seen anything suspicious. Waldrop, however, was aware of some facts that were supposedly known only to himself, his immediate superior. Captain John Holt, and Dallas Police Chief Billy Prince.

The morning after the strangulation, Waldrop had visited the reverend in the hospital suite he occupied just across from his stricken wife and conducted an interrogation that lasted almost three hours. Throughout that ordeal, the reverend appeared emotionally drained and extremely fatigued. He was slurring his words, the effect of some potent tranquil izers that had been prescribed at the hospital.

Waldrop had taken all of that into account, but still came away puzzled from his three-hour interrogation. Railey’s account of the events of April 21 and 22 was simple: he had been working on a research project until sometime after midnight at the Bridwell Library. The reverend said that he had phoned his house, received no answer, and, becoming alarmed, drove home to find his garage door partly open. The headlights of his car revealed the body of Peggy Railey, crumpled onto the garage floor.

But Waldrop found a hole in Railey’s alibi: Stephen Mbutu, a librarian at SMU’s Fon-dren Library, had told police that at around midnight, Railey had tried to check out a biography of Anne Sullivan. When told the book was not available, he became angry and stormed out of the library, In his talk with Waldrop, Railey had not mentioned entering Fondren anytime during the night.

And something strange had happened to the complex security system at the Railey house. One of the rumors circulating was that the system had been tampered with somehow, making the home vulnerable to an intrusion.

But a representative of the company that installed and monitored the system says that simply isn’t the case. “One of our technicians had checked the system out totally two days before the attack and it was totally operational,” he said.

“The only entrance to the house that wouldn’t trigger the alarm was the garage door. Mrs. Railey was aware of that. She was also equipped with a portable ’panic button.’ Our company prides itself on a three-minute response time anytime any of our clients’ alarms are triggered, and no alarm came from the Railey house that night,” the security specialist said. “And after the incident, we re-checked the system and there is no chance that there was any malfunction.”

That bit of testimony only adds to the intrigue. Why would Railey or his wife shut off the security system when he had been forced to wear a bulletproof vest during his Easter Sunday sermon just two days earlier? And why would Railey dare leave his wife and two children unguarded and unattended until past midnight, given the trauma of the alleged death threats? To make matters even stranger, a policeman at the crime scene had the impression that Railey had been drinking. A neighbor told police the same thing.

All of this was gnawing at Waldrop when he learned of a shocking break in the case. After extensive testing, the FBI had found that the notorious death threat letters were written on a typewriter in one of the offices of Railey’s own First United Methodist Church. Suddenly, things began to heat up.

In the days following the attack Railey continued to stay near his wife in Presbyterian Hospital, greeting a flow of sympathetic friends and church members. On the morning of May 1, however, Railey didn’t show up as usual outside Peggy’s room in Intensive Care. He didn’t answer phone calls to his room. When security guards finally forced their way into his room later that morning, he was found unconscious from an overdose of sleeping pills.

Incredibly, another sensational chapter now unfolded in the case. Now the Rev. Walker Railey, not his wife Peggy, was stretched out in an emergency room while two doctors and three nurses worked to save his life. It was not much of a struggle. The stomach pump revealed that Railey had gulped down about a dozen ten-milligram tranquilizers-enough to put the reverend into a sound sleep, but not enough to kill him. On the afternoon of May 2, Railey awoke to find both Dallas papers filled with banner headlines and stories about him. Among the details:

●Walker Railey had attempted suicide.

●He left behind a note claiming that therewere “demons within him” and that he was “tired of pretending to be good.”

●The police were investigating “inconsistencies” in his alibi.

●The FBI was saying that someone hadtyped the death threats right outside his veryown offic

Meanwhile, Waldrop was appearing before the television cameras. An interviewer wanted to know if Railey was a prime suspect. “We haven’t eliminated anyone as a suspect,” said Waldrop.

THE BULLETIN FOR THE 11 A.M. WORSHIP service at the First United Methodist Church on May 3, two mornings after the Rev. Railey had attempted suicide, made it seem that affairs would go on as usual. Following the service, there would be a lecture, “In Defense of Creation,” at noon in the Koinonia Room. At 1 p. m., a seminar on “Tax Reform and Decisions for Singles” would be con ducted in the Resource Center.

But the drawn looks on the faces of the congregation and church staff indicated that the services on this Sunday would be con ducted in an atmosphere that was clearly out of the ordinary. People stared at one another in undefinable silence, as if they did not know how to come to grips with the chaotic events of the week. Even in the nursery and preschool area, the usually festive atmosphere was subdued.

The Rev. John Yarrington’s huge choir, which customarily opens services with a grand processional down the aisles, this time filed quietly into the seats behind the altar. Then Gordon Casad, clad in his ministerial blue and gold robe, walked stiffly out before the congregation and offered some remarks that he’d been carefully scripting for the previous twenty-four hours. A church administrator and former district superintendent, he had been called in the previous summer to free Railey of some of the stresses of church management.

Understandably, Casad’s remarks had to be delicate. Not only was the congregation watching intently, the service was being telecast live on Channel 8’s “Hour of Worship.’ By now everyone was pondering the mystery that was Walker Railey. His story had also sent a chill wind of foreboding through many others in Dallas, churchgoers or not. This man had been a rock on which troubled people found rest; now, he seemed as vulnerable and weak as anyone else.

Some members of First United were also remembering that just two months before, Railey had preached a sermon that dealt with the topic of suicide. He said he was perplexed because four New Jersey teenagers had followed through with a pact and ended their lives together. “Maybe those four youths were just tired of the daily grind,” said Railey, “exhausted by the stress and strains of making it through the day, but with no sensation of having gone anywhere in the process. Perchance they felt life was nothing more than a dead-end street; that they were trapped in their situations; trapped in their lifestyles; trapped in their souls.”

But. trying to find hope in the midst of despair, Railey had said: “It is tragic that they did not perceive the other option. Instead of opting for life after death, they could have sought birth after life. Had they done so, they would be living today, and with abundance.”

The leader had not followed his own message. Whatever knowledge he possessed, it had not set him free. Now on this Sunday morning, Casad leaned toward the microphone to explain what had happened. He told them the most recent news of the Raileys. It was up to the congregation, he said, to “separate fact from fiction; truth from sensation.” He also said that perhaps “Walker had tried to move ahead too fast… and in the process, outdistanced the plans that God had had for him.”

Casad sat down. The hush was deafening.

The Rev. Susan Monts, one of several young ministers whom Railey had recruited to direct the church’s singles activities, came forward and offered the pastoral prayer. At one point she said, “The future is so uncertain; the present so meaningless.” Her voice broke for a moment.

When the service was over, the mood at the First United Methodist Church was anything but joyous. That same night, the CBS Movie of the Week attracted an unusually high share of the market on KDFW, Channel 4. The movie, titled “Murder Ordained,” was based on the true story of a Lutheran minister in rural Kansas. The minister and his girlfriend in the congregation had schemed to murder his wife.

BY THE SECOND WEEK IN MAY, IT HAD BE-come apparent to the lay persons in charge at First United that even though police continued to insist Railey wasn’t being singled out as a suspect, he’d already been indicted in the media, and, in the mainstream of public opinion, convicted of strangling his wife. Other rumors were flying, especially about the fiendish nature of the crime. One story had it that WD-40 had been sprayed down Peggy’s throat; another version said she had been hanged as if to indicate suicide; a third said she was found on the floor of the garage with her arms folded across her chest in a frozen, open-casket tableau.

Something had to be done. A three-mem- ber board of elders hired a prominent Dallas criminal defense lawyer, Doug Mulder, to represent the reverend-an unusual move considering that Railey had not been charged with a crime.

When Henry Wade’s DA’s office was mass-producing convictions throughout the Seventies, Doug Mulder was his chief prosecutor, and it was during this tenure that Mulder gained his reputation as Henry’s Hatchet Man, a person who would stop at nothing to send someone to Huntsville. Mulder abruptly jumped ship to the defense side in 1981 and had since taken on a number of front-page criminal cases, including his successful defense of sheriff Don Byrd on drunk driving charges.

The two made an unlikely combination- the man of God represented by the win-at-all-costs hard charger. Mulder was not at all bothered that his very presence might suggest some deep anxiety on Railey’s part. “If Railey’s worried about his public image,” Mulder said, “he should hire a PR guy and not a lawyer. It’s my job to keep my client out of jail. That’s all that matters.”

Mulder went directly to work. First, he arranged for the minister to be situated in comfortable temporary exile at the Timberlawn Psychiatric Hospital in far East Dallas. Then Mulder offered a simple suggestion to his client: don’t talk to the cops. The police kept saying they still needed the pastor’s help in developing clues as to who might have attacked his wife; they wanted him to clear up some “inconsistencies” in his account of his activities on the night of the crime. Railey, through his attorney, refused.

The lawyer then directed his client to submit to a polygraph test. One, on May 14, was privately administered by retired police officer Bill Parker. On May 15, Railey took a second polygraph, this one administered by police polygraph examiner William Bricker.

On the second lie detector test, Railey’s responses on the topic of the letters were deemed deceptive; his responses about the attack on his wife were “inconclusive.” Mulder had an explanation. “It was agreed upon beforehand that no questions would be asked regarding the threatening letters,” Mulder said. “But Bricker broke the agreement. Walker was confused.”

Mulder denied police allegations that Railey was refusing to cooperate with them. “I don’t know what inconsistencies they’re talking about,” he said.

A week later, Mulder and Railey slipped out of town to Salt Lake City for still a third test. When they returned to D/FW airport, reporters from Channel 4 News were there to greet them at the gate, and it was at this point that Railey. for the first time, seemed uncomfortable with his new place in the public eye.

The reporter, Bud Gillett, asked Railey about the nature of his travels that day. Railey looked at the microphone thrust in his face with the expression of a person who’d discovered a copperhead snake in the bathtub.

“No comment,” Railey snapped as he hurried to his car.

The downward spiral of the reverend’s fortunes intensified in June when Ralph Shannon, head of the Pastor-Parish Relations Committee that oversees personnel matters, announced at a news conference that Railey was being dismissed as senior minister at the First United Methodist Church.

The immediate effect of this would shatter any illusions held by Railey or his followers that he might someday, under some circumstances, return to the pulpit downtown.

Predictably, some concussive aftershocks rippled through the congregation, which suddenly found itself split into two camps: the group that had belonged to the church prior to Railey’s arrival and the element that had been attracted there by the dynamic young reverend. The pro-Railey faction felt that the manifesto to oust the reverend was, if anything, premature and certainly a cold and ungracious gesture to bestow on the man credited with bringing so much prosperity and vitality to the church.

Railey had privately communicated to some of his friends that, if he had to quit the church, he wanted the opportunity to stand before the congregation one last time and say farewell. The abrupt announcement from the committee seemed to be an insult, a kick in the teeth. Ken Menges, a thirty-year-old Harvard law graduate who typifies the kind of people the Rev. Railey attracted to the church, was immediately outraged at Ralph Shannon’s handling of the matter. Menges set about organizing a resistance movement within the congregation to protest the actions of the PPR committee.

The controversy continued the following Wednesday at the church, at a meeting that followed the regular weekly prayer meeting. A generation gap standoff was clearly at work, with Menges and thirty-two-year-old stockbroker Dick Thompson speaking on behalf of Railey. Ralph Shannon, head of the committee that fired Railey, has been a member at First United since 1950. Shannon’s position was that Railey himself had agreed to go along with the dismissal, to go quietly as it were, so the protest was unnecessary.

Eventually a behind-tjhe-scenes compromise was forged. Menges and his group would abandon the protest, since there was the threat of a civil war within the congregation if the movement persisted. The Pastor-Parish Relations Committee, in turn, agreed to continue paying a portion of Railey’s salary, which. With the fringe benefits of his office, was reportedly in the neighborhood of $100,000 a year.

AND THAT WAS WHERE THE CASE STOOD, smoldering, until one hot July afternoon when the chief prosecutor of the District Attorney’s office emerged from a meeting with Dallas homicide investigators. Norman Kinne, a man with a thick mustache, a penchant for cowboy boots, and a flair for the dramatic, had met with police to review the evidence in the Peggy Railey case. When he came out, surrounded by reporters, he was visibly angered by the photographs he had seen of the victim. He was also furious with Walker Railey. Kinne issued an angry-if unenforceable-challenge to the minister: Railey would either show up before a grand jury that would be investigating the matter, or he’d have to leave the country.

Kinne’s loud performance looked like something staged at ringside at Sportatorium wrestling matches, Some suspected that his blast might have been aimed more at attorney Mulder than at Railey himself, since the two attorneys have been rivals since their younger days together in the DA’s office. “There is nothing Norm would love to do more,” says Dallas attorney Jerry Banks, a former colleague of the two, “than to stick it in Doug’s ear in a high-profile case.”

So the gauntlet was flung down. Railey was subpoenaed to appear before the grand jury, as was someone else-Lucy Papillon, a member of First United. Papillon, a psychologist with frosted blonde hair and sparkling eyes, had been the object of whispered speculation for weeks.

The low talk around town had it that if the reverend was going to explore an outside love interest, he couldn’t have chosen anyone more strikingly different from his wife than the twice-divorced woman who had legally changed her name to Papillon. She did, however, share at least one similarity with Peggy Railey. According to the senior annual at Hockaday School, where the then Lucy Goodrich graduated in 1959, she intended to devote her life to some kind of church work, “perhaps through sacred music.” Peggy Railey holds a master’s degree in sacred organ music.

A classmate of Lucy’s at Hockaday, Becky Beasley, recalls that Lucy Goodrich was always a candidate for the Hockaday Ring that goes to girls who are regarded as leaders, who exemplify the kind of qualities that the school attempts to stand for.

“She must have been popular in a lot of circles at Hockaday,” says Beasley, who is now on the business faculty at the University of Texas at Arlington, “because she was a cheerleader. That was an honor.” According to the Hockaday annual, Lucy Goodrich was also a member of the Latin Honor Society, French Honor Society, and the Glee Club.

The profound shadow of Lucy’s father, Bishop Robert E. Goodrich Jr., would loom large over her life. A portrait of Robert Goodrich hangs in the foyer of the First United Methodist, where he served as senior minister before being appointed bishop in 1972. He died in 1985.

Lucy graduated from SMU in 1963 and married Jim Caswell one year later. If she were inclined to select a husband who would gain her father’s wholehearted approval, she could not have done better than Caswell, himself the son of a Methodist minister in Albuquerque. Caswell graduated from the Perkins Seminary in the mid-Sixties, and for a brief time served as associate pastor at First United. He later returned to SMU, where he is now dean of Student Life.

Jim and Lucy’s marriage lasted nine years. The split may have come about due to a growing restlessness on the part of Lucy to explore different pathways in life. This desire may have inspired her to visit Esalen, a sort of commune for free spirits and free thinkers of various persuasions who gather at Big Sur, California. Esalen disciples hope to undergo a spiritual and intellectual makeover. The goal is to elevate oneself to a higher plain via nutrition, nude bathing, and massage. The clientele is mostly Califor-nian, but followers come from all over. It was at Esalen that Lucy Caswell decided to take on her identity as “Papillon,” French for butterfly.

She moved to California where she served an internship at the University of California Medical School at Irvine near Los Angeles. She later returned to Dallas, where she remarried, this time to another psychologist, Irwin Gadol. That union, too, was destined for divorce in 1981.

Her friendship with Railey began in 1984 when both appeared on a television panel discussion group. The relationship would lead Lucy Papillon into the grand jury and from there into sensational headlines, According to phone records, Railey had called Papillon twice from his car phone, at 5:58 p.m. and again at 7:32 p.m., on the night his wife was attacked. Again, Railey had not mentioned these calls in the interview with Lt. Waldrop.

Through the days leading up to the grand jury hearing, the gossip mill went wild. Church members steeled themselves for another round of revelations. They had little idea what was to come.

On the day of the grand jury hearing, Railey emerged from the elevator on the seventh floor of the county courthouse into a throng of thirty-five reporters and cameramen gathered in the hallway. He tried to walk quickly through the crowd to the grand jury room.

“Walk more slowly, Reverend!” bellowed one of the cameramen.

“More slowly? All right,” said Railey. Railey seemed to be pitched into a momentary dislocation. There he was, once the beloved church leader, his bald head gleaming like a polished helmet under the camera lights, his eyes dark, his face white and withdrawn.

After Mulder threw a couple of verbal left hooks at Norman Kinne (“He [Kinne] orchestrated and created this circus-like atmosphere that you see today.”), the attorney then reaffirmed his client’s innocence. “If you’re going to create an alibi, you’d better create a better one than Walker did,” the lawyer said.

Was it true, then, that the reverend would plead the Fifth Amendment to any question Kinne asked him?

“That’s the beauty of the Fifth Amendment. You don’t have to explain anything to anybody,” said Mulder. “I don’t think we’re losing anything. The cloud’s still over his head. He can’t clear the air, and unless someone else comes forward and confesses to attacking Mrs. Railey, Walker will never remove the cloud.”

It turned out Railey did plead the Fifth, which allows a person to avoid incriminating himself. In fact, he invoked the privilege forty-three times, according to anonymous sources. But that bit of news didn’t create half the uproar that came when word leaked about the testimony of Lucy Papillon.

WHILE WALKER RAILEY ENDURED THE DIF-ficult solitude of the grand jury witness room, Papillon confronted the twelve-person panel and apparently confirmed that she and the reverend had been romantically involved. She said that she and Railey, since June of 1986, had traveled out of town together on more than one occasion. In the summer of 1986, Railey had traveled to Kenya to attend a worldwide religious conference and had stopped over in London for a liaison with Papillon on the return trip. Papillon said that she and the reverend had discussed the possibility of marriage. She also testified that she had met with Walker Railey in his hospital suite at Presbyterian after his wife had been strangled, and that they had kissed.

And finally, Papillon testified that she had no knowledge of the events that happened at Railey’s home on the night of April 21, but she did say that she and the reverend had been together for about a half hour, at her home on Daniel Avenue near the SMU campus, earlier on the night of the attack.

Though it is illegal for an official privy to grand jury testimony to make it public, someone was secretly telling all-and the news scandalized the city. For the first time, many began to view Railey as a pathetic person, seemingly possessed by a love for his church, yet haunted by something else.

Although a man might still remain a pastor if he’s a suspect in a murder, committing adultery is an entirely different matter. Church spokesman Ralph Shannon said that discussions were under way to remove Railey’s portrait from the wall in the church foyer. In late August, Railey’s salary was dropped from the church payroll. On September 2, the beleaguered pastor resigned as a Methodist minister-a move that may have preempted efforts on the part of the church hierarchy to defrock him.

“I guess you might perhaps compare Walker to Icarus,” says Dick Thompson, referring to the mythological figure who flew too close to the sun.

Only Railey’s father, back in Kentucky, maintains a spirited public defense of his son. “Why would he want to strangle his wife?” asks Chester Railey. “Why would he want to do that? He had the finest congregation in Dallas, preaching on Channel 8 down there, a beautiful family, making good money, and probably about to become one of the youngest Methodist bishops in the United States. Tell me why. It makes absolutely no sense.”

That, perhaps, is the sad coda to this story: it makes no sense. Railey’s church, which lived with such passionate definitions, now finds itself passing through a strange, horrifying crisis; it has become an unwilling repository of questions, doubt, and bitterness. If Walker Railey is guilty of the accusations against him, many church members now ask, does this mean that what he has told us all these years, the message he has brought to change our lives-does this mean it’s all untrue?

Police are still asking for anyone who knows what might have happened on Trail-hill Drive to come forward. Privately, however, they know that as each day passes, the chances of solving the crime grow even smaller. Meanwhile, Peggy Railey lies- “more dead than alive,” as Norm Kinne puts it-in the Tyler nursing home. Many people wonder what will happen to the Railey’s two children.

And many others wonder what will happen to Railey himself. The day we sat in his kitchen, he told me that he needs a job. He has considered teaching, or perhaps a career in writing. “I also realized if I do something impulsive,” he said, “it could affect my life for the next twenty-five years.”

For now, Walker Railey conducts his private morning devotionals, he plays golf, and he tries to hold off the police, who are searching everywhere for something that might link the reverend with the attack on his wife, the attack Railey says he knows nothing about.

IN DALLAS, THE ATTACK ON PEGGY RAILEY hangs in the air like an oppressive cloud. And it has left a lingering sadness that no one can fully explain. The Rev. Bill Bryan recalls walking into the sanctuary of First United Methodist Church one weekday not long ago. There, in the emptiness, Bryan heard the voice of a little boy singing the children’s song, “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” Bryan looked around and finally saw Ryan, Railey’s five-year-old son.

“He was sitting by himself up in the balcony,” says the Rev. Bryan, still haunted by the memory, “and he was holding a hymnal upside down and singing.”

Ryan’s tiny voice bounced against thewalls of the sanctuary and washed over thepulpit where his father once stood. Here,where Walker Railey had brought so manyto hear the good news of God’s mission forman, young Ryan and others, wiser andolder, were left to ponder mysteries that, forthe moment at least, seem to have noanswers.

The Night of April 21

Investigators still have unanswered questions about Walker Railey’s activities on the night his wife was attacked. Combining police accounts, phone records, and Railey’s own story, here is a chronology of what is known about that night.

5:55 p.m.-Railey calls his house on the car phone.

5:58-Railey calls Lucy Papillon at her office.

6:30-Railey arrives at his home on Trailhill Drive, talks with his wife as she attempts to lubricate a lock on the garage door with a bar of soap.

6:38-Railey calls for the time from his car phone.

Between 7-7:30-Peggy Railey talks on the phone with a friend; tells the friend that she’s fine and discourages her from coming by.

7:26-Railey calls the family babysitter on the car phone and discusses plans for the family’s trip out of town later in the week.

7:32-Phones Lucy Papillon’s home on Daniel Avenue near the SMU campus from his car phone.

Between 7:40-8:15-Visits Papillon at her home.

Between 8-8:30-Railey appears at the Bridwell Library at SMU and asks the librarian what time it closes.

8:30-Railey phones Peggy from a pay phone at the library. She tells him she is putting the children to bed.

8:49-9:14-Peggy Railey talks long distance to her parents in Tyler.

8:53-Railey buys gas at a Texaco station at the 4700 block of Greenville Avenue.

9:30-A jogger in the Lake Highlands area sees a man in a business suit and street shoes running through a yard two houses south of the Railey home.

10:15-10:30-A woman who lives immediately behind the Raileys hears suspicious noises in the bushes.

10-11-Railey is seen at the Fondren Library at SMU.

Midnight-Railey attempts to give his business card to the librarian, listing research information he is seeking. He leaves the library shortly thereafter.

12:03-Railey calls his house from his car phone and receives no answer. At 12:29 he calls again; no answer.

12:40-Railey enters his driveway, notices the garage partly open, and finds Peggy lying unconscious on the garage floor.

12:43-Railey goes to a neighbor’s house. The neighbor calls the police.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte

Business

New York Data Center Developer Edged Energy to Open Latest Facility in Irving

Plus: o9 Solutions expands collaboration with Microsoft and Dallas-based Korean fried chicken chain Bonchon to open 20 new locations.

By Celie Price

Restaurants & Bars

Where to Find the Best Italian Food in Dallas

From the Tuscan countryside to New York-inspired red sauce joints, we recommend the best of every variety of Italian food available in North Texas.